In the Athenian neighborhood of Skouze Hill, a pair of shabbily dressed men, Polish immigrants, sit on a doorstep across the street from a supermarket, wearily asking passersby for change as they wait for store employees to throw away the day’s unsold food. Once the food has been tossed into the supermarkets’ dustbins, they will compete with the area’s other dumpster divers—ethnic Roma—for the stale bread and leftover vegetables.

When he illegally immigrated to Greece two decades ago, Yannis Lubovicki, forty-three, dreamed of a better life than what Poland—then struggling to adjust to a post-Berlin Wall world—could offer. Instead, he and his companion Christos Gabriel, fifty-three, found poverty. Now they spend their days panhandling and their nights sleeping on park benches. They survive on food from church soup kitchens and trash cans and the water from park fountains. Once a week they walk downtown to Koumoundourou Square and use the public baths there, well frequented by the homeless.

“Don’t give them any money,” says a well-dressed middle-aged woman heading into the supermarket. “They’ll spend it on wine in a split second.” If harsh, her words are perhaps true: their breath smells of alcohol, their eyes are bloodshot, and Lubovicki—the woman points to him emphatically—is timidly taking a corkscrew out of his bag.

An estimated one person in twenty is an undocumented immigrant in Greece, a country of eleven million. Many of them, like Lubovicki and Gabriel, are transplants from the former Eastern bloc. Having moved to Greece in search of the economic opportunities that an integrated, prosperous Europe once offered, they have instead struggled to survive, one of the groups hardest hit by financial crisis in Greece—itself one of the countries hardest hit by the global recession that struck in 2007. At the same time, they have been scapegoats for the country’s ongoing malaise, with high unemployment and political turmoil—along with a humiliating dose of international ridicule for the former continental success story turned basket case—feeding a brutal, anti-immigrant backlash within Greek society, just as they have in other immigrant magnets such as Italy, Malta, and Spain.

Yet in few corners of Europe have ultranationalism and xenophobia gained as much traction as they have in Greece. Golden Dawn, a far-right Greek political party, has seen tremendous growth since the economic crisis hit. In 1996, it received just 0.07 percent of the vote in national parliamentary elections; in 2012, it won 7 percent. Halting immigration is the party’s chief goal. Its leaders declare that “illegal alien-invaders” amount to an irregular foreign army, one bent on attacking the country’s social fabric and corrupting its national identity. The party’s extreme rhetoric has, in turn, fed violence, from the murder of a Greek antifascist rapper by a party member, to the stunning attack that Golden Dawn MP Ilias Kasidiaris unleashed on two leftist members of parliament during the live taping of a morning talk show. (After their argument grew heated, Kasidiaris—who has called Greece’s undocumented immigrants “human garbage”—punched Communist MP Liana Kanelli and threw a glass of water in the face of SYRIZA MP Rena Dourou.) Golden Dawn members have frequently harassed immigrants, going so far as to pose as police in order to intimidate street vendors.

Even in Athens, Greece’s cosmopolitan capital, Golden Dawn has substantial support. It won 16 percent of the vote in last May’s mayoral elections, a huge jump from its share of just 5 percent in 2010. “We have been swarming with Albanians, Pakistanis, Africans, and Eastern Europeans,” says the middle-aged woman at the supermarket, who did not give her name. “Now we have the Gypsy gangs, too.” Her once-affluent neighborhood used to be populated by high-ranking military officers and their families, but in recent years the poorer immigrant enclaves in the bordering downtown areas have spilled over here as well.

“That’s why they wanted us in Europe, “she adds—referring to wealthy northern European nations like France and Germany—“to keep the Third Worlders away from them so they can continue their petty little lives.”

Gangling and gray-haired, Gabriel walks with a limp and speaks with a thick accent. In his halting Greek, he notes happily that he recently discovered a new hideout, a tiny covered alley alongside a newly built apartment building, where he lies down on the pavement at night to sleep. He and Lubovicki have spent the last five years living in close proximity to the supermarket and its surplus food. Until a few months ago, they had been squatting in a nearby abandoned house, but then the landlord drove them out.

Gabriel has been in the country for twelve years. Back in Poland, he lived through the early years of his homeland’s transition from communism. Post-Soviet Poland quickly reformed its economy to woo investors, privatizing its coal and steel industries and knocking down regulatory hurdles. Thanks to vigorous economic growth and rising standards of living, Polish households were optimistic and exuberant, and credit flowed easily. Gabriel, then a coal miner, decided to take out a loan to buy a two-story house in the southern Polish city of Katowice for himself, his wife, and four children.

The Polish “miracle,” however, failed to curb the country’s high levels of unemployment. Laid off and unable to find a new job, Gabriel struggled to pay his 50,000-euro mortgage. Desperate, he immigrated to Greece in 2002, joining a wave of illegal immigrants drawn by the global image of pre-crisis Greece as flourishing and full of promise. (Today, there are about 50,000 Polish immigrants in the country.) Gabriel has not seen his children since he left.

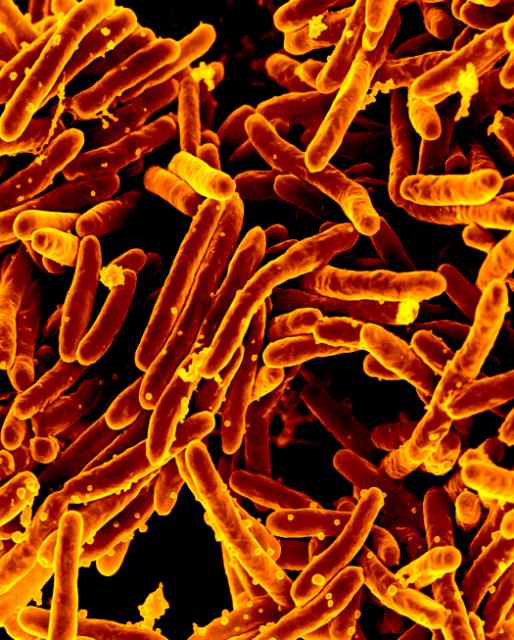

But today’s moribund Greek economy—now in its seventh year of recession—now offers little in the way of hope for Gabriel and immigrants like him. In Athens, about 5,000 undocumented immigrants live in derelict buildings unfit for human habitation. When they can find work, conditions are often extreme: migrant strawberry pickers, for example, earn $26 to $33 a day for about ten hours’ work, living in makeshift huts with no access to toilets. Meanwhile, government officials warn of a “public-health time bomb,” with large numbers of new immigrants not inoculated for tuberculosis, polio, measles, and other communicable diseases.

Until the 1990s, Greece was an extremely homogenous society. The wave of Eastern European immigrants that flooded Greece after the fall of the Soviet Union was followed by another wave of immigrants from Africa and Asia in subsequent years, gradually ratcheting up anti-immigrant sentiment among the broader population. Today, as unresolved economic and immigration problems worsen an already festering resentment; Greece continues to vie for the title of Europe’s “most racist” nation.

In recent years, the government has had some success in stanching the flow of illegal immigrants into the country, which it credits in part to an eight-mile barbed-wire fence it erected along its border with Turkey, completed two years ago. The number of illegal immigrants that the government detained fell from 77,000 in 2012 to 43,000 in 2013.

These days, Gabriel stays on constant alert for police raids—not for fear of deportation (European countries, Poland and Greece included, signed the 2007 Schengen agreement that allows citizens of each country to move and work freely throughout the union), but for fear that he may be arrested for failing to pay his bank loan back in Poland. For the most part, thought, the police tend to ignore him and other homeless immigrants.

Golden Dawn wishes it were otherwise. These foreigners must be deported, the party argues, in order to save the culture and community of the “pure” Greeks. (Ironically, in spite of his slogan of “work for Greeks only,” Golden Dawn’s leader, Nikolaos Michaloliakos, happens to own a hotel in an immigrant Athens neighborhood staffed by low-wage foreign workers.) Beyond its anti-immigration platform, Golden Dawn has argued for building closer ties with Russia at the expense of the US (particularly in regards to energy resources), erasing the “illegal” Greek debt and voiding the terms of the country’s internationally funded bailout, purging the public sector, and walling the Greek economy off from global trade.

In recent months the party’s brazen militancy seems to have backfired to some extent, with two of its leaders now in jail awaiting trial—Michaloliakos for forming a “criminal organization” and a spokesperson for gun charges. Nevertheless,Nikos Kyriakidis, a forty-seven-year-old plumber from Athens, insists that Golden Dawn is the only party that will fight against Zionism, imposed multiculturalism, and the growing erosion of Greek culture. Economic anxieties also seem to be at the root of Kyriakidis’s anger. He rails against the “scumbags” of PASOK and New Democracy—the major political parties that have long run the country—that he says destroyed the Greek economy. Although he has a quarter-century worth of work experience, right now Kyriakidis is unable to support his family. They just moved to avoid living in a part of the city that has recently seen an influx of immigrants. Kyriakidis doesn’t want his children to grow up in such a rundown neighborhood, he says.

In Greece, Eastern European immigrants tend to fare better than other immigrants in one area: racist attacks. Three weeks ago Gabriel and Lubovicki witnessed a gang of thirty young men dressed in black beating Asian immigrants. “They shouldn’t have hit them, it’s not right,” says Lubovicki, a stubby and gregarious man who fills in the silences of his tall and taciturn companion. The beating took place out in the open, in a public square with numerous passersby. Four police officers were nearby but did nothing, Lubovicki claims. Fortunately, the gang did not bother the two Poles. “It is the dark ones they are after,” he notes—that is, the Pakistanis, Afghanis, Syrians, Bangladeshis, Somalis, and Eritreans who have built up the country’s largest Asian and African immigrant enclaves.

“The men were huge—real giants,” Lubovicki adds. “If one of them punched me in the face, my head would fall off.”

A group of young men walk down the street, stopping when they notice Lubovicki and Gabriel—half-drunk and reeking of alcohol—sitting on the doorstep. “I’ll give you ten bottles of wine if you kick this car door,” says one of the men. He is short and fair-haired, in his early twenties.

“Ten more bottles if you sing,” says another, a hulking man with a humpback.

Lubovicki bursts into laughter and says he can’t do it. Gabriel cracks a smile.

The young men seem to know the Poles. They, too, are immigrants—second-generation Albanian Greeks. Many of their parents immigrated to Greece after the Soviet Union collapsed. (Today, those of the country’s unauthorized immigrants who hail from the former Eastern Bloc are chiefly from Albania: in 2013 they were almost a third of all illegal immigrants arrested that year, and Albanians also comprise a majority of the country’s total foreign-born population.)

Lubovicki has a daughter of his own, now seventeen years old. (Her name is Despoina, a Greek Orthodox name; Lubovicki converted to the Greek Orthodox faith after arriving in the country.) His marriage ended after his wife, who had moved out to Greece with him, found out about an affair. “We had a brawl,” he says. “My wife left Greece in the middle of the night with my daughter.”

Things really got bad when Lubovicki lost his job during the crisis. “I haven’t worked in five years … I was a construction worker,” he says. (The construction sector—which used to employ both men, and whose workforce is a third foreign-born—has shrunk by half since 2009.) “I’ve been a vagabond all these years, sleeping on the benches of the parks.” He smirks as he admits it.

Their descent into poverty has soured their attitudes toward the free market and made the two Polish immigrants nostalgic for Poland’s communist era—however repressive it was. They would never have left Poland if the Soviet Union had not collapsed, they point out. Back then, life was good, and they lacked nothing. Thanks to the government, Lubovicki adds, he attended a trade school.

These are views shared by a significant number of older Eastern Europeans, according to a 2009 Pew survey. While those under the age of forty tend to favor the economic and political reforms their countries have gone through over the past two decades, the older generations are more skeptical. Clearly, many have painful memories of the USSR: not just the absence of freedom and dissent, but also the frequent shortages of food and toilet paper, the constant lecturing about Marxist-Leninist creeds, the degrading monotony of Soviet life. But like Lubovicki and Gabriel, some of those who grew up under communism point out that unemployment and homelessness were virtually unknown back then. Their salaries were nowhere near American ones, but the cost of living was negligible. The Soviet educational system was excellent, ranking among the best in the world.

In recent years, Poland has, like Greece before it, seen rapid economic growth. While many Poles continue to go abroad in search of the higher wages to be found out west, living standards have improved back in their home country. Lubovicki points out that his mother, a professional chef, enjoys a pension and a cozy house of her own. Meanwhile, he lives on the streets.

Lubovicki misses his hometown, a village outside Warsaw. He misses his daughter, who speaks to him by phone every other week. He misses his mother’s cooking. But he does not believe he will go back to the old country anytime soon. “My mother calls me up all the time asking me to return to Poland, but I can’t because I can’t afford it. I need eighty-five euros to renew my passport and about 200 euros for travel expenses.”

It’s not just about the money, Lubovicki adds. Born “Yannus,” he has lived as “Yannis” since he came to Greece—now half his life. “If I go to Poland, I won’t know a thing. I’ll be unable to adjust there …. I have been living in Greece ever since I came of age, how am I supposed to start all over again?” Gabriel—who used to go by the name “Yaroslav”—nods in approval.

“Have I told you I am also a mechanic for all kinds of machines and can do some plumber work?” Lubovicki says, moving on to another, more hopeful, topic. “I may find a gig like this in the future. I know the tools of the trade.”

Then his eyes light up. The sliding doors of the supermarket have opened. Employees bearing huge trash bags head for the dustbins. Lubovicki walks over to find his next meal.

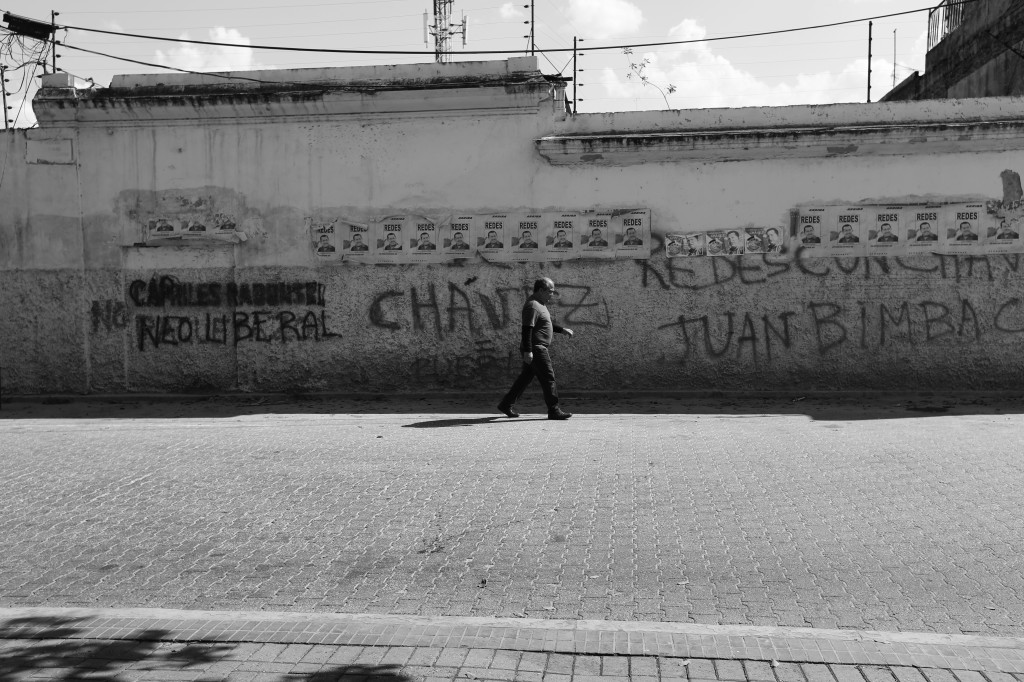

Correction, September 27: An earlier version of this article misidentified the man in the first photo. It is Yannis Lubovicki, not Christos Gabriel.

Stav Dimitrοpoulos Stav Dimitropoulos is a writer and journalist whose work has appeared in major US, UK, Australian, and Canadian outlets. A native of Greece, she received the Athens Medal of Honor at the age of seventeen and went on to receive a master's degree. She experimented with journalism along the way, and has been writing ever since. Facebook | Twitter: @TheyCallMeStav

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content