It is an honor to be here today. This is an inspiring place because of you and the first lady, and because of the film exhibited across the way in the Presidential Library. For those who have not seen it, it shows the president as a young pilot, shot down during the Second World War, being rescued from his life-raft by the crew of an American submarine. It is a moving reminder that when America has faced challenge and peril, Americans rise to the occasion, willing to risk their very lives to defend freedom and preserve our nation. We are in your debt. Thank you, Mr. President.

Mr. President, your generation rose to the occasion, first to defeat Fascism and then to vanquish the Soviet Union. You left us, your children, a free and strong America. It is why we call yours the greatest generation. It is now my generation’s turn. How we respond to today’s challenges will define our generation. And it will determine what kind of America we will leave our children, and theirs.

Americans face a new generation of challenges. Radical, violent Islam seeks to destroy us. An emerging China endeavors to surpass our economic leadership. And we are troubled at home by government overspending, overuse of foreign oil, and the breakdown of the family.

Over the last year, we have embarked on a national debate on how best to preserve American leadership. Today, I wish to address a topic which I believe is fundamental to America’s greatness: our religious liberty. I will also offer perspectives on how my own faith would inform my presidency, if I were elected.

There are some who may feel that religion is not a matter to be seriously considered in the context of the weighty threats that face us. If so, they are at odds with the nation’s founders, for they, when our nation faced its greatest peril, sought the blessings of the Creator. And further, they discovered the essential connection between the survival of a free land and the protection of religious freedom. In John Adams’ words: "We have no government armed with power capable of contending with human passions unbridled by morality and religion … Our constitution was made for a moral and religious people."

Freedom requires religion just as religion requires freedom. Freedom opens the windows of the soul so that man can discover his most profound beliefs and commune with God. Freedom and religion endure together, or perish alone.

Given our grand tradition of religious tolerance and liberty, some wonder whether there are any questions regarding an aspiring candidate’s religion that are appropriate. I believe there are. And I will answer them today.

Almost 50 years ago another candidate from Massachusetts explained that he was an American running for president, not a Catholic running for president. Like him, I am an American running for president. I do not define my candidacy by my religion. A person should not be elected because of his faith, nor should he be rejected because of his faith.

Let me assure you that no authorities of my church, or of any other church for that matter, will ever exert influence on presidential decisions. Their authority is theirs, within the province of church affairs, and it ends where the affairs of the nation begin.

As governor, I tried to do the right as best I knew it, serving the law and answering to the Constitution. I did not confuse the particular teachings of my church with the obligations of the office and of the Constitution — and of course, I would not do so as president. I will put no doctrine of any church above the plain duties of the office and the sovereign authority of the law.

As a young man, Lincoln described what he called America’s "political religion" — the commitment to defend the rule of law and the Constitution. When I place my hand on the Bible and take the oath of office, that oath becomes my highest promise to God. If I am fortunate to become your president, I will serve no one religion, no one group, no one cause, and no one interest. A president must serve only the common cause of the people of the United States.

There are some for whom these commitments are not enough. They would prefer it if I would simply distance myself from my religion, say that it is more a tradition than my personal conviction, or disavow one or another of its precepts. That I will not do. I believe in my Mormon faith and I endeavor to live by it. My faith is the faith of my fathers — I will be true to them and to my beliefs.

Some believe that such a confession of my faith will sink my candidacy. If they are right, so be it. But I think they underestimate the American people. Americans do not respect believers of convenience.

Americans tire of those who would jettison their beliefs, even to gain the world.

There is one fundamental question about which I often am asked. What do I believe about Jesus Christ? I believe that Jesus Christ is the Son of God and the Savior of mankind. My church’s beliefs about Christ may not all be the same as those of other faiths. Each religion has its own unique doctrines and history. These are not bases for criticism, but rather a test of our tolerance. Religious tolerance would be a shallow principle indeed if it were reserved only for faiths with which we agree.

There are some who would have a presidential candidate describe and explain his church’s distinctive doctrines. To do so would enable the very religious test the founders prohibited in the Constitution. No candidate should become the spokesman for his faith. For if he becomes president, he will need the prayers of the people of all faiths.

I believe that every faith I have encountered draws its adherents closer to God. And in every faith I have come to know, there are features I wish were in my own: I love the profound ceremony of the Catholic Mass, the approachability of God in the prayers of the Evangelicals, the tenderness of spirit among the Pentecostals, the confident independence of the Lutherans, the ancient traditions of the Jews, unchanged through the ages, and the commitment to frequent prayer of the Muslims. As I travel across the country and see our towns and cities, I am always moved by the many houses of worship with their steeples, all pointing to heaven, reminding us of the source of life’s blessings.

It is important to recognize that while differences in theology exist between the churches in America, we share a common creed of moral convictions. And where the affairs of our nation are concerned, it’s usually a sound rule to focus on the latter — on the great moral principles that urge us all on a common course. Whether it was the cause of abolition, or civil rights, or the right to life itself, no movement of conscience can succeed in America that cannot speak to the convictions of religious people.

We separate church and state affairs in this country, and for good reason. No religion should dictate to the state, nor should the state interfere with the free practice of religion. But in recent years, the notion of the separation of church and state has been taken by some well beyond its original meaning. They seek to remove from the public domain any acknowledgment of God. Religion is seen as merely a private affair with no place in public life. It is as if they are intent on establishing a new religion in America — the religion of secularism. They are wrong.

The founders proscribed the establishment of a state religion, but they did not countenance the elimination of religion from the public square. We are a nation "Under God," and in God, we do indeed trust.

We should acknowledge the Creator as did the Founders — in ceremony and word. He should remain on our currency, in our pledge, in the teaching of our history, and during the holiday season, nativity scenes and menorahs should be welcome in our public places. Our greatness would not long endure without judges who respect the foundation of faith upon which our Constitution rests. I will take care to separate the affairs of government from any religion, but I will not separate us from "the God who gave us liberty."

Nor would I separate us from our religious heritage. Perhaps the most important question to ask a person of faith who seeks a political office is this: Does he share these American values: the equality of human kind, the obligation to serve one another, and a steadfast commitment to liberty?

They are not unique to any one denomination. They belong to the great moral inheritance we hold in common. They are the firm ground on which Americans of different faiths meet and stand as a nation, united.

We believe that every single human being is a child of God — we are all part of the human family. The conviction of the inherent and inalienable worth of every life is still the most revolutionary political proposition ever advanced. John Adams put it that we are "thrown into the world all equal and alike."

The consequence of our common humanity is our responsibility to one another, to our fellow Americans foremost, but also to every child of God. It is an obligation which is fulfilled by Americans every day, here and across the globe, without regard to creed or race or nationality.

Americans acknowledge that liberty is a gift of God, not an indulgence of government. No people in the history of the world have sacrificed as much for liberty. The lives of hundreds of thousands of America’s sons and daughters were laid down during the last century to preserve freedom, for us and for freedom-loving people throughout the world. America took nothing from that century’s terrible wars — no land from Germany or Japan or Korea; no treasure; no oath of fealty. America’s resolve in the defense of liberty has been tested time and again. It has not been found wanting, nor must it ever be. America must never falter in holding high the banner of freedom.

These American values, this great moral heritage, is shared and lived in my religion as it is in yours. I was taught in my home to honor God and love my neighbor. I saw my father march with Martin Luther King. I saw my parents provide compassionate care to others, in personal ways to people nearby, and in just as consequential ways in leading national volunteer movements. I am moved by the Lord’s words: "For I was an hungered, and ye gave me meat: I was thirsty, and ye gave me drink: I was a stranger, and ye took me in: naked, and ye clothed me …"

My faith is grounded on these truths. You can witness them in Ann and my marriage and in our family. We are a long way from perfect and we have surely stumbled along the way, but our aspirations, our values, are the self-same as those from the other faiths that stand upon this common foundation. And these convictions will indeed inform my presidency.

Today’s generations of Americans have always known religious liberty. Perhaps we forget the long and arduous path our nation’s forbearers took to achieve it. They came here from England to seek freedom of religion. But upon finding it for themselves, they at first denied it to others. Because of their diverse beliefs, Ann Hutchinson was exiled from Massachusetts Bay, a banished Roger Williams founded Rhode Island, and two centuries later, Brigham Young set out for the West. Americans were unable to accommodate their commitment to their own faith with an appreciation for the convictions of others to different faiths. In this, they were very much like those of the European nations they had left.

It was in Philadelphia that our founding fathers defined a revolutionary vision of liberty, grounded on self-evident truths about the equality of all, and the inalienable rights with which each is endowed by his Creator.

We cherish these sacred rights, and secure them in our constitutional order. Foremost do we protect religious liberty — not as a matter of policy, but as a matter of right. There will be no established church, and we are guaranteed the free exercise of our religion.

I’m not sure that we fully appreciate the profound implications of our tradition of religious liberty. I have visited many of the magnificent cathedrals in Europe. They are so inspired, so grand, so empty. Raised up over generations, long ago, so many of the cathedrals now stand as the postcard backdrop to societies just too busy or too "enlightened" to venture inside and kneel in prayer. The establishment of state religions in Europe did no favor to Europe’s churches. And though you will find many people of strong faith there, the churches themselves seem to be withering away.

Infinitely worse is the other extreme, the creed of conversion by conquest: violent Jihad, murder as martyrdom … killing Christians, Jews, and Muslims with equal indifference. These radical Islamists do their preaching not by reason or example, but in the coercion of minds and the shedding of blood. We face no greater danger today than theocratic tyranny, and the boundless suffering these states and groups could inflict if given the chance.

The diversity of our cultural expression, and the vibrancy of our religious dialogue, has kept America in the forefront of civilized nations even as others regard religious freedom as something to be destroyed.

In such a world, we can be deeply thankful that we live in a land where reason and religion are friends and allies in the cause of liberty, joined against the evils and dangers of the day. And you can be certain of this: Any believer in religious freedom, any person who has knelt in prayer to the Almighty, has a friend and ally in me. And so it is for hundreds of millions of our countrymen: We do not insist on a single strain of religion — rather, we welcome our nation’s symphony of faith.

Recall the early days of the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia, during the fall of 1774. With Boston occupied by British troops, there were rumors of imminent hostilities and fears of an impending war. In this time of peril, someone suggested that they pray. But there were objections. They were too divided in religious sentiments, what with Episcopalians and Quakers, Anabaptists and Congregationalists, Presbyterians and Catholics.

Then Sam Adams rose, and said he would hear a prayer from anyone of piety and good character, as long as they were a patriot. And so together they prayed, and together they fought, and together, by the grace of God, they founded this great nation.

In that spirit, let us give thanks to the divine author of liberty. And together, let us pray that this land may always be blessed with freedom’s holy light.

God bless this great land, the United States of America.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

A woman’s struggle to face down social anxiety disorder.

A woman’s struggle to face down social anxiety disorder.

Returning Burundis face land clashes.

Returning Burundis face land clashes.

Why Uganda’s victims don’t want The Hague to prosecute.

Why Uganda’s victims don’t want The Hague to prosecute.

When battling obesity means fighting the body you’re born with.

When battling obesity means fighting the body you’re born with.

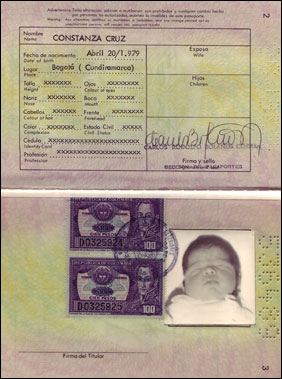

Transnational adoptees come of age and search for home.

Transnational adoptees come of age and search for home.

Spinning the present into the past.

Spinning the present into the past.