The circle of adoption

Flor Rojas, who has run the FANA adoption agency in Colombia for 35 years, and won numerous humanitarian awards there, has the cordial, almost outdated mannerisms of Colombia’s patrician upper class: pearl-wearing Catholics who have their hair done regularly at the salon. Rojas has no children of her own, nor did she adopt. But she has single-handedly placed over 10,000 Colombians with families all over the world.

For Cerami, and other FANA adoptees, Rojas represents all the unknowns in an adoptee’s life — a passage to what Betty Jean Lifton, who wrote the first influential adoptee memoir Twice Born in 1975, calls “the Ghost Kingdom of what might have been.” Rojas had met Linda and Michael, a young couple from Long Island with love to spare, and a young mother, in a bind, from the hot Upper Magdalena valley.

Rojas gets calls all the time — “on a daily basis,” she says — from adoptees, but few actually come to visit. Even fewer, she says, seek, let alone find, their biological parents. (McGinnis’s research confirms this, finding over 90 percent of adoptees “wanting” to find their birthmother, but only a quarter actually “engaged” in a search.) And even so, Rojas is careful to point out, those who persist tend to have bad experiences. Parents don’t want to be found. The desperation that led to adoption in the first place has not been overcome; the birthmother begs financial support. There are culture and language divides. Adoptees mistakenly see reunion as an end rather than a beginning. Rojas understands the longing, she says, but tries to shelter the curious from possible harm.

The children eventually come to see the orphanage as their origin, Rojas says, and are “always thankful” to have been moved. “Seeing the place that gave them an opportunity in life is useful for people who wonder who they are.” Rojas calls what the biological mothers do “the supreme loving sacrifice.”

When Cerami landed in Colombia, she found Bogotá different from the violent and impenetrable city she had seen on CNN. Still, the homeless there were somehow more gruesome to her than the homeless in Manhattan. She could see the desperation. At her friend’s bachelor party, Cerami stumbled through a conversation about opportunity. She toured a cathedral carved out of a defunct salt mine, stood in line at the national registry, and visited city notary number 20, where her birth certificate had been filed.

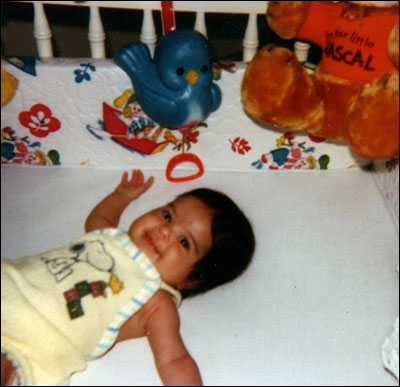

At the orphanage, Cerami met the 30 children there. Rojas says there could have been up to 250 when Cerami was chosen. The orphanage is clean, spacious, well-equipped. The children were shy at first, but quickly make friends. One boy’s chapped cheeks and striped long-sleeve shirt provoked Cerami’s longing to take one home. The others showed the full array of Colombia’s racial diversity, mugging for Cerami’s camera, where they liked to see themselves in the LCD display. It wasn’t long before Cerami was crying, excusing herself to the bathroom. The oldest orphan, an 11 year-old, followed her to ask why. Cerami told her, “Because I was you.”

A couple that had arranged to pick up a child was in town, and Cerami was offered the chance to perform the ceremonious exchange, as a way to “complete her circle of adoption.”

Before the ceremony, though, Rojas pulled Cerami into her office. FANA’s brick walls are covered with framed portraits of the thousands of children who have been sent overseas. Beside Rojas’s glass-topped desk, the poem “Legacy” describes two equally loving mothers and a split, fortunate child. “The door’s closed,” Rojas told Cerami. “There’s nobody else around. What do you want to know?”

Cerami wanted to know how she had been chosen for the Cerami family. “It was God,” Rojas said, “who has His hands in all things. Couples ask if they can pick their children, and we reject them. Because you can’t pick the child you’re going to give birth to.” But Rojas, in turn, wanted to know what had become of the child, what she had made of herself. It is her life that matters, not her origins, she said. Then, lightly, Rojas asked if Cerami wanted to see her file. “I’ve had it pulled for a few days now. It has been sitting here waiting for you.”

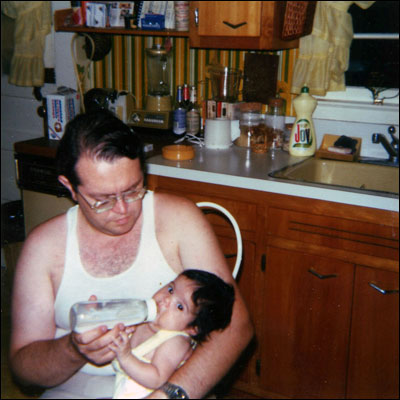

The folder was opened on the desk. Yellowed pictures Linda Cerami had sent with her application, of herself and her husband Michael, fell into view. The birth certificate for Constanza Cruz, from 1979. And a single, lined worksheet, completed in the judicious, slanting hand of a Colombian office worker — what little information Cerami has on her biological mother.

She worked as a housemaid. She had a 4 year-old daughter. She was 22, and her motive for giving up the child she had carried for five months was economic: “with two children I can’t work. I want the best for my children,” someone had written for her.

On the form, the “father of the future baby” is allowed two lines of features and illnesses. The description is cryptic: tall, trigueño, green eyes. It’s the classic Colombian handsome man, his skin color compared to wheat. Trigueño is on the whiter side of dark, as a 19th-century Spanish dictionary describes it, “in the same way a person of lighter color, milky with a pink hue, is called white.” Cerami all of a sudden wondered if her children will have green eyes.

Now she says her mother’s name as if reciting a lesson, in three descending beats, careful to tap the r’s off the roof of her mouth: Hortencia Cruz Leon.

She has entered the Ghost Kingdom. The search to become whole makes her more fragmented. Cerami realizes that she is not ready to “open a whole can of worms,” she says. “I have enough family to last a lifetime.” She will take time to get to the know the orphanage, and promises to return, but finding her mother can wait.

Rojas watched, then told Cerami it was time to present the child. A family from Buffalo, with a first adopted son, Sebastian, accepting a second, Austin, in his little Baby Gap clothes. As Cerami tells it, he gazed up at his new mother as if he were meant to be with her.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

Transnational adoptees come of age and search for home.

Transnational adoptees come of age and search for home.