“Ideally, when I’m spinning, you walk into a trans-temporal universe,” he says. “It’s a weird, nostalgic time warp.” To create the effect, Jacobs pays particular attention to the sequence and selection of the songs he plays, using the dancers and other visual cues as tools. “I’m framing them in a different way than they’ve ever been played live before,” he says. “I’m using my imagination and my passions to present the songs in a completely fresh way. I’m sharing my emotional responses to the music.” He says he wants his audience to time travel with him, to hear the sounds of yesteryear as they were meant to be heard. In turn, he’s spurred on by the emotional responses he sees in his listeners.

“They hear a song, they’ll come over, they see the album spinning, they see the record players, and all of this adds layers to their experience,” he says. “Everyone has their own version of nostalgia. There is time traveling going on.”

One wonders if he wishes he could go back in time in order to make things turn out differently. A dream lost, a vision unfulfilled? Jacobs will only say that he’s always thought it would be interesting to visit another time, noting that if he actually lived in the past, he’d probably fit in and therefore “be boring.”

In any case, Jacobs is peddling something brilliant and seductive and magical, something that speaks to the latent nostalgia in everyone, even if you weren’t aware that you were nostalgic about anything.

Some, at least, seem to pick up on this — even if they’re unaware of The Vintage DJ himself. In line for the bathroom at the Valentine’s Day party, not many barflies knew who was spinning, but most endorsed the music full-heartedly — if drunkenly. “It’s like being a kid again!” gushed one attendee. “I don’t remember the name of this song, but I love it!” said another. When Jacobs played the Crystals’ “Then He Kissed Me,” every girl in the room was up on her feet, bouncing and squealing. On one hand, Jacobs’ knowledge of era-specific tunes far outweighs that of his listeners — at least at this party — and the level of attention and nuance he accords to his choice of songs may often get lost in the crowd. Then again, on a night so awash in alcohol, isn’t it the essence of the evening — the feeling — that lingers in the memory the next day?

Any chance he gets, Jacobs tries to connect with people over records — where they came from, which tracks are best, how best to play and listen to them. “Some records, you can barely hear them because so many people before you have held that same record and listened to it,” he says with a touch of wonder. When people approach him at a gig, he has no problem letting them sift through record jackets or even handle albums.

What he’s really grasping at is human connection in a world gone mad with machines.

What is lost

Jacobs has developed such a dislike for what he sees as needless technology that he recently tried to return a $600 cell phone he found in a cab. Unable to reach the owner, he’s selling it on eBay rather than keeping it for himself: He says he doesn’t need it. He’s turned off by the rise in popularity of things like online grocery delivery services, wondering why people can’t just go to the store. “If people could have their groceries emailed to them, they would!” he complains. Fueling his irritation is the fact that technology often seems to have the unintended consequence of making things more difficult. “The crappy thing about the Internet is that Internet music providers have bought up all the discography, so when you try to look up the discography of a particular artist the search comes up with all the albums you can buy instead of the history of which albums the artist made and when they were released,” he laments.

“Actually, it’s like the song ‘Rat Race’ by The Drifters,” he continues, getting lost in thought. “The guy is talking about why he does it all, he says he’s going to win … but everything is really just to keep the machine going so you can end up getting a crappy retirement and one can of beans a week.”

Jacobs expands, becoming more excited. “The past is a relic, and a relic is eventually rejected because people can’t make money off of it,” he says. “That’s why our world is so fucked up, because now so much is based on corporations and money. In the past, art seemed to be so much more a part of everyday life. People don’t ask if you still have your first DVD player, because it’s obsolete. But whole pieces of furniture were built for record players.”

True, but isn’t that the natural outcome of societal progression?

“We’re getting to the point where we’ll be able to do everything naked, we won’t need anything else. We’ll just think something and it will happen,” he answers.

What is lost when that happens?

The Vintage DJ sighs and bends over his record player.

“Everything,” he says.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

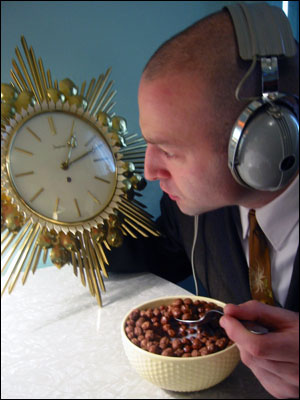

Spinning the present into the past.

Spinning the present into the past.