Smashed grapes

In his long, narrow ground floor apartment off a busy street in Brooklyn, The Vintage DJ doesn’t seem out of place. The Lovin’ Spoonful’s “Darling Be Home Soon” echoes lazily, melancholically, from the trapezoidal speaker grills of the record player in the corner. A porcelain statue of Nipper the dog — Barraud’s infamous phonograph-listening canine — stands at attention on the shelf, ears cocked. It makes you want to listen too, because it’s just so easy and nice. Lots of stylish young adults who fall somewhere in between the hipster, hippy, and aging punk persuasions inhabit similar apartments in this area, with equally retro-inspired furnishings. And therein lies the paradox: The Vintage DJ, with his orange table lamps and vinyl collection, appears to fit right into the trendy masses here. But he doesn’t. He is perhaps too authentic. And yet, by chasing success, he runs the risk of losing his authenticity, or of alienating himself when he discovers that not everyone shares quite his level of love for ancient LPs.

Then again, maybe he’ll inspire converts. As The Vintage DJ roams about his tiny living room, running his fingers lightly over the tips of thousands of neatly ordered records (alphabetized by genre and title), it’s not difficult to fall under the spell of history and longing.

If it were 1963 — one of Jacobs’ favorite years, musically, of all time — he would have invited you to come over and listen to records. As he played you a song, you’d hold the album cover in your hands, touching the softened cardboard edges and feeling the sharp endpoints of the corners, perhaps catching a whiff of the musty inner fold. The record would crackle a little sometimes, that delicious, delicate popping woven through the sultry vocal vibrations and humming violins. You’d close your eyes, he’d tap his fingers to the beat. When the song was over, he’d ask you how you liked it, and you would tell him. A total, communal, tactile interaction between two people and a song. As Jacobs will tell you, nothing like today.

Jacobs is into layers and amplification, and loves the cool jazz, brassy sounds of the early- to mid-1960s. But today’s most popular musical format — digital — lacks the friction of a needle on a record, which provides a much deeper listening experience, he says.

“If someone wants to share a song now, they just go wrrrrp and there you go,” he says, miming pushing a button on an MP3 player. “It’s like smashing up a grape in your hands and handing it to someone. It’s totally empty: with digital music, there’s actually gaps. MP3s literally hold music in, shrink it. Listening to a record is a physical experience, like putting two pieces of metal together: when they touch, it’s like a flash in a cartoon. But when its digital, there’s no event. It’s just computers and data.”

Not that Jacobs is living in some sort of cave: he has a cell phone, an iPod, and even a MySpace account. He also recognizes the value of technology and is keen on the use of digital recordings, both video and audio, as an archiving tool. His grandfather — who died when Jacobs was three — recorded hundreds of hours of film footage of his family from the 1930s through the 1960s; Jacobs recently transferred some of it to DVD, laying down music from his own collection to match.

Watching him watch the black and white images moving ghostlike across the screen, it’s clear that The Vintage DJ is motivated by something beyond sight and sound — it’s the emotion evoked by those sights and sounds that he’s trying to tap into when he spins. It doesn’t have to be his emotion, though he says he picks music based on the emotional response it stirs in him; sometimes someone at a gig will come up to him, and he knows he’s done it again.

At an art opening where Jacobs was spinning Hank Williams’ “Dear John,” a gentleman in his late 60s approached him in a trance. “I was playing a ’78, and you could really hear the crackle and the whirring of the record,” he says. “It was a very particular sound and this man had a very particular emotional response, maybe a very particular memory, a farm or his mom’s apron, and he hobbled up to me totally watery eyed and thanked me.” A listener to his weekly radio show, “The Time Machine,” (Wednesdays, the brutal slot from midnight to 2 a.m.) emailed from Paris to thank him. That’s when he knows he has to forge onward, even though he pays East Village Radio for the airtime.

Time travel

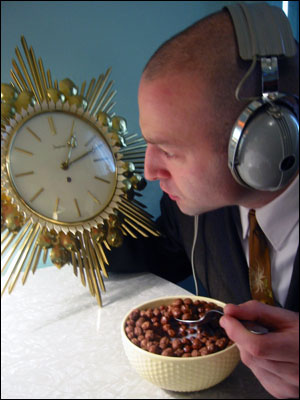

“Wouldn’t it be cool if bands never aged and the Zombies were still 20 years old?” The Vintage DJ ponders this question in relation to his favorite group as he lugs one of his most cherished possessions — an old phonograph — from the hallway closet, setting it on the coffee table. He nestles the album into place, pumps the lever vigorously, and leans his nose close to the vinyl in order to place the needle precisely in the right groove.

There’s something thrilling about the sound of an old song played in this manner. Wilson Pickett, Mose Allison, Little Johnny Taylor might as well be in the room with you, whereas playing them on your iPod (literally the closest you can get physically to the sounds of their voices) just makes them sound louder. The record player adds dimension, filling the singers’ voices with breath and vibrations and making them sound … real.

Of course, just because this music sounds so good doesn’t mean modern music is bad, right? Well, while The Vintage DJ believes everyone is entitled to his or her own personal tastes — and certainly doesn’t begrudge people who fawn over, say, Britney Spears — his own preferences are pretty particular.

“People don’t understand quality anymore,” he sighs. “I’m tortured by my tastes, but I have to indulge them because otherwise I feel unhealthy.”

This notion that modernity has ushered in an element of decay — and that the past is somehow more wholesome — is nothing new, and seems to resurface every decade. But if Jacobs is to succeed, he will have to maintain at least some commonality with his listeners. And that might be one of his greatest challenges, because the better he gets at what he does and the more records he collects, the more out of step the rest of the world will likely seem.

“I got in a fight with someone at a bar once,” he reveals. “They said I was selfish because I only play songs that I like — which isn’t true — whereas the traditional definition of a DJ is someone who plays what’s popular, what people want to hear.”

People like that, The Vintage DJ feels, miss the point. Jacobs couldn’t be bothered with modern music; he’s dealing in a much richer currency — musical memory, music as memory, memory and music.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

Spinning the present into the past.

Spinning the present into the past.