A catch in Amilcar Arroyo’s Spanish-accented voice conveyed his shock and hurt as much as his words. The slender, bright-eyed legal immigrant told a mix of Latinos and Anglos in the common room of a city church that, after 18 years of living in his adopted country, he recently felt as though he were an outsider once again. While covering a press conference at which Mayor Louis Barletta announced he would run for a third term, Arroyo, president of a Latino media company, found the silent animosity among his fellow U.S. citizens nearly palpable.

“I felt the atmosphere there. People there looked at me like a leper,” Arroyo said.

Arroyo would discover that feeling shunned was only the beginning. Asked if he would renew his support for Barletta, Arroyo said no. Arroyo had endorsed the mayor in a previous campaign but a pair of anti-illegal immigration ordinances Barletta spearheaded led Arroyo to withdraw his support. The day after the press conference Arroyo heard from a dozen callers criticizing his change of heart. Some said they had previously considered him an honest man and a respected community figure, but that his comments about the mayor had changed their views. Other calls were more ominous. “You’d better watch out. You’d better take care of yourself because you’re going to get hurt,” Arroyo said one caller warned.

Arroyo spoke at a January 22 meeting convened in the common room of Faith United Church of Christ by the Greater Hazleton Ministerium, an interfaith clergy association. The Ministerium does not take an official position on the ordinance and is seeking common ground between those on both sides of the issue. Attendees included residents, clergy, city Latino leaders, a representative of the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission and a Luzerne county commissioner. A big-eyed baby watched the discussions from an infant carrier slung over his mother’s shoulder.

One of the ordinances would have prohibited renting to undocumented immigrants and called for a $1,000 per day fine for landlords who did so. Of the 4,216 rental units in the city, 236 are Latino-occupied, according to the 2000 U.S. Census. Another ordinance would have revoked the business permits of establishments which employed illegal immigrants.

Legal challenges have prevented the ordinances from being enforced although their original versions were passed in July. In response to a lawsuit by advocacy organizations, landlords and residents, U.S. District Court Judge James Munley in October deemed the ordinances temporarily unenforceable and is slated to determine the long-term fate of the laws this month. If enforced, the laws could disrupt the education of child citizens who must leave the country with their deported parents, force a plaintiff who is a legal immigrant to be evicted because she is waiting for documentation of her status, and hurt the profits of business owners and landlords, Judge Munley stated in court papers explaining his decision.

Although the ordinances are intended to curb crime, city officials did not offer statistical evidence that increasing immigration has caused an increase in crime, Judge Munley said. The city has passed revised versions of the ordinances, which critics say have harmed the Latino community even though the laws are not in effect.

“It sort of became open season on a lot of Latinos, regardless of their status,” said Fabricio Rodriguez, executive director of Philadelphia Area Jobs With Justice, which organized a September rally opposing the ordinances. Racist graffiti, vandalism and fights in school are some of the problems local Latinos reported when Rodriguez surveyed them on the impact of the ordinances.

The ordinances address only illegal immigration, but xenophobic hecklers have taken them as a cue to publicly harass legal immigrants along with those who lack papers because it is impossible to differentiate the two groups based only on appearance, said Agapito Lopez, vice president of the Hazleton Area Latino Association and a member of the Governor’s Advisory Commission on Latino Affairs, in a telephone interview. Cultural differences make innocent Latinos seem suspect to their Anglo neighbors and the ordinances embolden residents to express their suspicion, Lopez said. Latinos frequently meet outdoors to share jokes and stories as they do in their native countries, Lopez said.

“When they see people gathering outside and speaking a different language, they think it’s a gang,” Lopez said. Far from being meetings of criminal cabals, the outside gatherings merely reflect how many Latinos’ sensibilities differ from those of many Anglos, Lopez said. “We don’t like to be inside because we come from tropical countries,” he said. Some Anglos’ misperceptions have led them to lash out at their Latino neighbors, Lopez said.

“There are people who are being called names in the street,” Lopez said.

Struggles to cross a racial divide

On a frigid January day shortly after the Ministerium meeting, people did not appear to linger in the street long enough to insult or be insulted. On Broad Street, the Roads End Pub and Club was dark inside and below the Blues Brothers statues on its facade a sign stated “All Legals Served.” A hat-snatching wind rushed down Wyoming Street, where well-kept older model cars lined the curbs. The vivid yellow clapboard walls of Lechuga’s market offered the eye a welcome change from the gray-stained gobs of old snow piled along the icy sidewalks. Latino grocery stores chock-a-block with sundries and tropical products, money transfer bureaus and travel agencies shared the street with employment agencies and Italian restaurants. A handful of stores stood empty; some had permits taped to their plate glass windows suggesting that new occupants were preparing to move in.

Those who work on Wyoming Street, noted for its concentration of Latino businesses, said that the consequences of the ordinances are economic as well as interpersonal. Owners of establishments that primarily serve Latinos have seen a drop in business which they trace to the ordinances. One grocery store employee said business had declined by about five percent since the ordinances passed because many immigrants have left town after raids by federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents.

“Immigration came down here and took people away,” said Julian Figueroa, an employee of Jazmin’s Grocery on Wyoming Street. Immigration officials did not target Jazmin’s, but did visit businesses on Wyoming Street, Figueroa said one recent afternoon after waiting on a young customer whom he advised about keeping track of her small bills. Other business owners also noticed a decline in customers.

“A lot of people just left town. You notice the drop at least as far as the money transfers that you do, calling card sales which is more of what the immigrant population buys,” said Chris Rubio, an employee of Isabel’s Gifts on Wyoming Street while staffing the counter at the shop one recent weekday. Some businesses have closed due to lack of customers. Rosa and Jose Luis Lechuga, plaintiffs in the lawsuit, closed their restaurant due to a decline in business, according to court papers. The restaurant served 45 to 130 customers before a previous version of the ordinances passed, but had only six or seven patrons daily afterward. The Lechugas’ Latino grocery store served 95 to130 customers a day before the ordinances passed, but had 20 to 23 patrons daily afterward. Jose Lechuga said by phone on January 30 that he was moving to Texas and had sold the store. The city does not keep statistics on business owners’ nationality so municipal employees do not know how many Latino-owned businesses have closed or how many new immigrant-owned establishments have opened since the ordinances passed.

City officials said the ordinances were intended to protect city residents from crime, not to harm Latinos socially or economically. Shootings committed by undocumented immigrants inspired the ordinances, said Joe Yannuzzi, council president, who supported the ordinances. Municipal law did not provide for punishing crimes committed by undocumented immigrants, Yannuzzi said by phone.

Shootings are rare occurrences in the city which had about 23,000 people as of the 2000 Census. Latino advocates have said that the population has increased by about 10,000 people since 2000. Mayor Barletta has said in published reports that the population had increased by at least 7,000 since the last census. “The only thing we could do is punish the people who are here legally,” Yannuzzi said. City officials began by exploring the appropriate response to several recent shootings, and later noticed a connection between the crimes and undocumented immigrants, Yannuzzi said.

“The violent crimes were being committed by illegal aliens,” Yannuzzi said. The ordinances allow the city to protect all residents, including Latinos, Yannuzzi said. “They live here the same as we do. They don’t want to see shootings either,” he said. Yannuzzi said that Latino residents’ departures should not cause concern that Hazleton’s population has nose-dived. Those who left were quickly replaced by other Latinos, he said. “The place is still booming and there’s a lot of Latinos still living here attending the schools and getting along with everybody,” Yannuzzi said.

A fellow council member echoed Yannuzzi’s concern with crime but had voted against the ordinances. “The rationale should have been to combat crime,” said councilman Bob Nilles in a telephone interview. Nilles opposes tying anti-crime ordinances to immigration issues because doing so creates legal problems for the city.

Those who attended the Ministerium meeting also expressed concern with violent crime and said that opposing it could be a common cause for those who might disagree about the immigration ordinances. “We know violence has gone up. We know that violence is connected to the drugs,” said the Rev. Tom Cvammen of Trinity Lutheran Church in West Hazleton, who facilitated the meeting.

With a calm voice and demeanor, the Rev. Cvammen appeared ready to help attendees stay focused on the goal of reconciliation should the conversation become overheated. Some who attended the Ministerium meeting said that focusing on crimes committed by illegal immigrants obscures a general increase in crime related to drug sales in the city. One attendee objected to the Mayor’s emphasis on illegal Latino immigrants when he endorsed the ordinances and touted them a means of stemming crime.

“He failed to mention that a non-Hispanic killed my cousin,” Anna Arias, president of the Hazleton Area Latino Association and a member of the Governor’s Advisory Commission on Latino Affairs, said sharply. Mayor Barletta did not return calls. Arias said that the person who killed her cousin had sold drugs and that he committed suicide after the crime. The room was silent.

Attendees defined reducing drug sales and other crimes as a primary goal of one of the three working groups that formed at the meeting. Members of each working group gathered around a folding table in the common room to brainstorm and develop action plans. The working groups included Latinos and Anglos who were Jews, Catholics, Protestants, Quakers and those who did not state a religious affiliation. Almost all appeared to be in their forties or older. Members of the working group on crime planned to invite David Wilkerson, founder of Teen Challenge, an international Christian-based drug rehabilitation and education program, to speak to members of church youth groups throughout the city. The crime working group also planned to invite members of Unidos, a diversity group at Hazleton Area High School, to the next Ministerium meeting on February 27.

Members of the working group dedicated to addressing public fears of Latinos said they sought to reduce fear by replacing it with the truth about people of whom others might be afraid. “A lot of the fear is based on untruth or exaggerations,” said the Rev. Jane Hess of Faith UCC. Group members considered creating a public forum in which immigrants would share their memories of becoming citizens. “At that moment, you have to put aside the country where you were born. You have to love this country a lot to do that,” Arroyo said.

To help community members get to know each other across ethnic divides, a third working group planned a series of cross-cultural activities. The working group planned to connect events for the May 3 National Day of Prayer to the Cinco de Mayo (Mexican Independence Day) celebrations and to dedicate the day to appreciating diversity. Working group members also planned to ask organizers to dedicate this year’s Fun Fest to celebrating diversity and to ask Wyoming Street merchants to hold a block party to coincide with the annual festival of music, food and crafts. The working group intended to start an inter-ethnic hiking and biking club for young people.

An age-old debate

Attendees have reason to hope for greater inter-cultural understanding, the Rev. Cvammen said. Catholics and Protestants once divided the city into sections along religious lines and used to attack each other on the streets of Hazleton but have long since ceased segregating themselves and brawling. Discrimination against Italians, Irish and Poles also used to be common in the city, Lopez and Arias said. “It’s something that was worked on before,” the Rev. Cvammen said.

The ebbing of historic inter-group tensions in Hazleton makes the city representative of a national trend. A century ago, public immigration debate centered on determining if Greeks and Poles could fit into U.S. society, said Randy Capps, senior research associate at the Center on Labor, Human Services and Population at the Urban Institute, a non-partisan research organization. Historic immigration debates have subsided nationwide only to be replaced by new ones.

“Now we’re debating whether or not immigrants from Mexico and Latin America are going to fit in,” Capps said. Attitudes of those participating in current debates are shaped by a different set of experiences than their early 20th century predecessors. Although the U.S. has historically been a nation of immigrants, many politicians now in office came of age during a 40-year period of relatively low immigration, Capps said. Immigration slowed between the 1920s and the 1960s due in part to ceilings on the number of people who could enter the U.S. from each country. The Great Depression also made the U.S. less attractive to immigrants seeking to escape poverty in their native lands. “We went through a period when we weren’t country of immigration, so it seems new and out of control,” Capps said.

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 have also changed attitudes toward immigration. The hijackers who crashed airliners into the Pentagon, the World Trade Center and the Pennsylvania countryside were legal immigrants, but their actions have shaped attitudes toward those who enter the country with or without documents. Some U.S. citizens believe that cracking down on illegal immigration ensures national security.

“People feel they are acting against terrorism,” said Myriam Torres, director of the Arnold School of Public Health Consortium for Latino Immigration Studies at the University of South Carolina. Latino immigrants who enter the country intending to do harm are rare, Torres said. “The majority of immigrants from Latin America, they are not coming to commit crimes, they are coming to work,” Torres said. Immigrants who do not have enough money to qualify for visas often enter the country illegally to assist their families by taking jobs rejected by U.S. citizens, Torres said.

“They will do anything they are asked to do, because they know whatever they are earning here, even if it is a low wage, it is much higher than they would be earning at home,” Torres said. Policymakers seeking to control illegal immigration should address the human costs of a global economy in which developing countries fare poorly, Torres said. “I do think that there is a need to work with the countries who are sending people here,” Torres said.

Sharlee Joy DiMenichi

Dear Reader,

In The Fray is a nonprofit staffed by volunteers. If you liked this piece, could you

please donate $10? If you want to help, you can also:

A few years ago, author Jonathan Lethem found himself well on his way to becoming the Philip Roth of Brooklyn with his two most well-acclaimed novels, Motherless Brooklyn (1999) and The Fortress of Solitude (2003) — both colorful and incisive accounts of his hometown borough — quickly propelling him into the somewhat reluctant role of a Brooklynite mouthpiece.

A few years ago, author Jonathan Lethem found himself well on his way to becoming the Philip Roth of Brooklyn with his two most well-acclaimed novels, Motherless Brooklyn (1999) and The Fortress of Solitude (2003) — both colorful and incisive accounts of his hometown borough — quickly propelling him into the somewhat reluctant role of a Brooklynite mouthpiece.

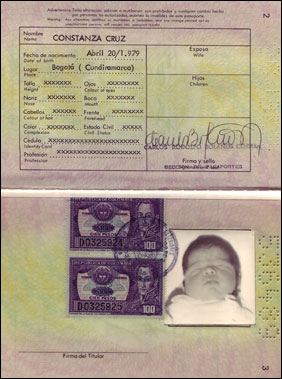

Transnational adoptees come of age and search for home.

Transnational adoptees come of age and search for home.

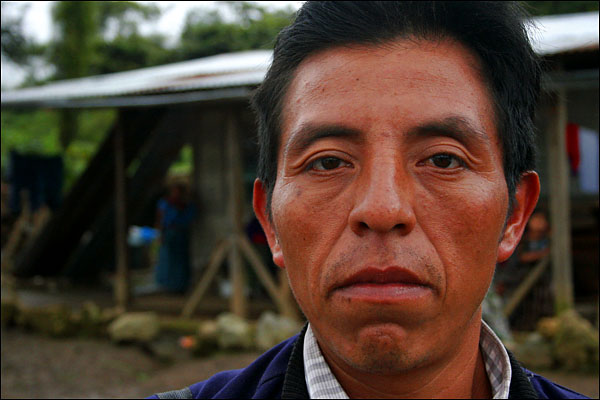

Post-war reparations in Guatemala.

Post-war reparations in Guatemala.

How traveling puts turning 30 into perspective.

How traveling puts turning 30 into perspective.

Spinning the present into the past.

Spinning the present into the past.

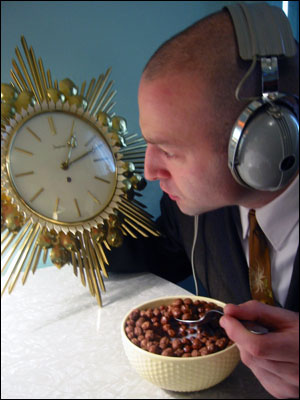

A quirky look at the first gray hair.

A quirky look at the first gray hair.