In Riyadh for a business trip, I found myself with a couple of hours to kill. I decided to wander around Al Olaya, the Saudi capital’s commercial core and upscale shopping district. In a gleaming shopping mall surrounding my hotel, I saw familiar brand logos on either side, a glitzy array of high-end storefronts much like those you’d find in any major Western city—except for the stylized Arabic lettering. Eventually, I came across the garish window display of a Victoria’s Secret. There I stopped, amazed.

![]() I had actually lived in Riyadh two decades earlier, having come to Saudi Arabia to work as a physician. At the time, there were no Victoria’s Secret stores to be found. The company’s website was even blocked by the religious authorities. Women could buy lingerie, but they had to do so in a general store—and all the shops back then were staffed exclusively by male attendants (women were not allowed to work in most public spaces). All these prohibitions had made shopping for intimate apparel a singularly humiliating experience.

I had actually lived in Riyadh two decades earlier, having come to Saudi Arabia to work as a physician. At the time, there were no Victoria’s Secret stores to be found. The company’s website was even blocked by the religious authorities. Women could buy lingerie, but they had to do so in a general store—and all the shops back then were staffed exclusively by male attendants (women were not allowed to work in most public spaces). All these prohibitions had made shopping for intimate apparel a singularly humiliating experience.

So much had changed in Saudi Arabia, and it wasn’t just about the overt femininity of a lingerie store. I walked into another familiar Western store, a Louis Vuitton boutique. The fall collection was being displayed—luxury scarves, elegant handbags—much the same as it would be in New York City. The mannequins wore shorts and dresses with bare plastic legs. But what captured my attention were their heads—molded plastic, with detailed facial features. Two decades ago, that depiction of the female form was forbidden. The mannequins back then would have been headless.

I must have looked ever so slightly lunatic in that store, gawking at the mannequins. Soon enough, a store clerk approached me, and we began talking about my impressions of the new Saudi Arabia. A group of attendants—all of them, notably, women—began to gather, curious about my excited chatter. I explained to them that when I lived in Riyadh, the mall had a designated floor just for women, the only place in this mall where we were allowed to shop. Even having that women-only space had been an advance at the time; other malls would only let women shop during restricted hours when men would not be present.

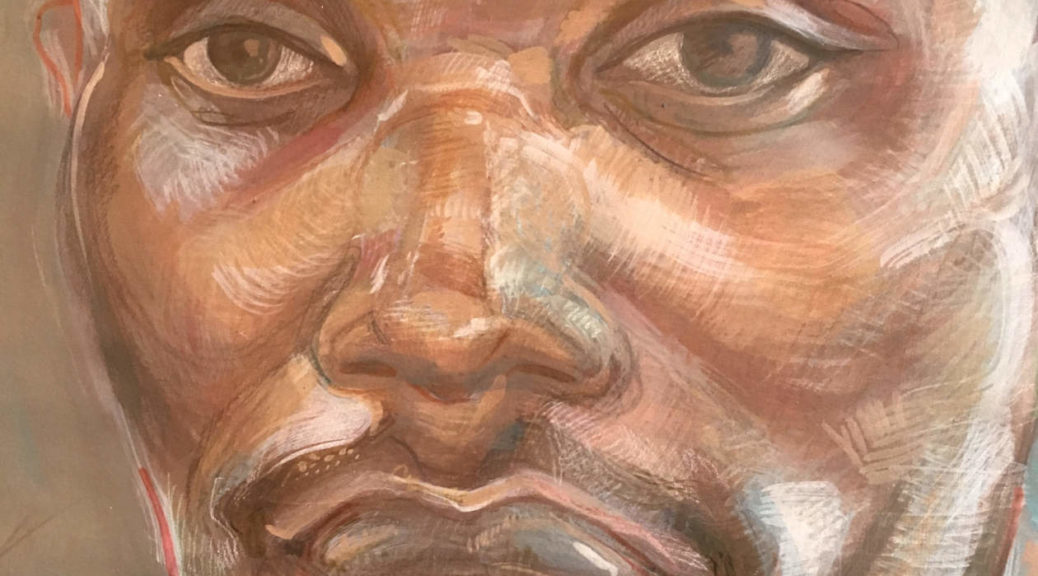

As I told the women about their country’s recent past, I felt like a time traveler speaking of unimaginable sights. All the store clerks were young—not surprising in a country where two-thirds of the population is under thirty. While some of them wore headscarves, others did not. They seemed to find my enthusiasm infectious, and they asked many questions. We ended our impromptu chat with the conclusion that, yes, this was Islam: the freedom for a woman to choose how to observe, to choose how to be.

Since I’ve returned from my trip, I’ve thought often about how much Saudi Arabia has changed—and whether another Muslim country, Iran, might take a similar path. For several months beginning in September, Iran was paralyzed by massive protests unlike any the country had seen since the 1979 revolution. The spark of this explosive rage was the suspicious death of Mahsa Jina Amini, a twenty-two-year-old Kurdish Iranian woman who had been detained by police for “improperly” wearing her hijab.

Continue reading An Endgame for Iran: A Saudi-Style Revolution from AboveQanta A. Ahmed Qanta A. Ahmed, MD, is a senior fellow at the Independent Women’s Forum and a life member of the Council on Foreign Relations.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content