Last March, I was working in Montana as a ski instructor at the Big Sky Resort. When the pandemic reached the United States and stores started shutting down, I remember meeting up with friends for a potluck dinner. We drank Coronas and joked about the toilet paper shortage.

Three days later, the resort closed—an unprecedented six weeks early—and we were all out of jobs. My friends and I threw an impromptu end-of-season party at the local dive bar. There was an edge to that evening, though. It seemed that no one could sit still or hold a calm conversation.

A week after the resort closed, my boyfriend, who lived in Tennessee, called. There were rumors that states were going to shut their borders to keep the virus from spreading. “I don’t want you to be stuck in Montana away from me,” he said.

“What do you think I should do?” I asked.

“I want to come get you and move you back to Tennessee with me.”

I had intended to move in with my boyfriend after the ski season ended, but this would be two months earlier than planned. With some hesitation, I agreed. I didn’t want to leave my friends in Montana, but I didn’t want to have to deal with a pandemic on my own, either.

Once we got back to Tennessee, though, our plans began to unravel. That summer I was supposed to return to my seasonal job as a whitewater kayak instructor on the Ocoee River, but the state lockdown shut down that possibility. Instead, I sat by myself on the couch, day-drinking and watching Netflix. My boyfriend worked alone from morning till dark on various projects around his unfinished house.

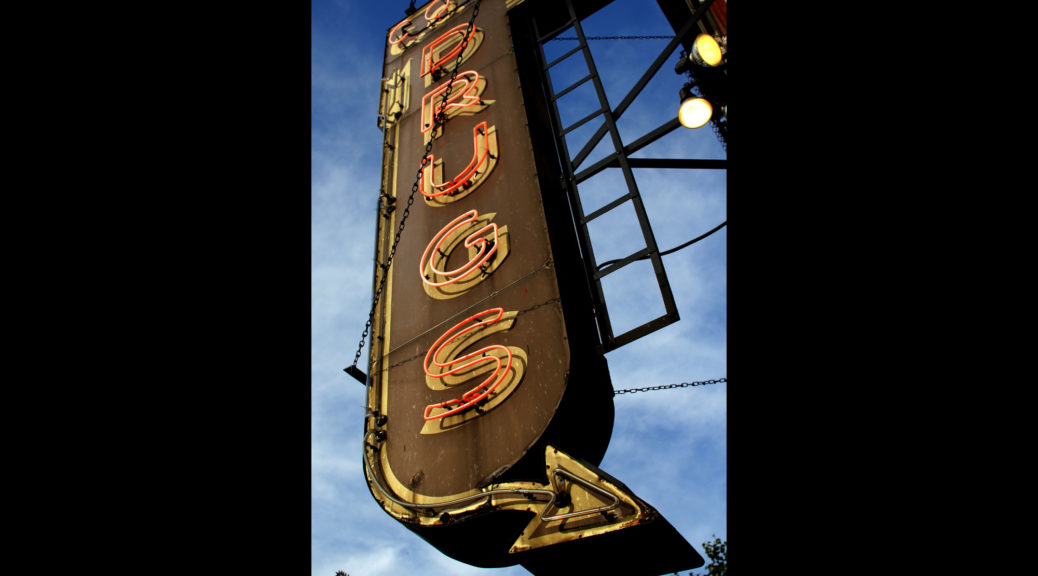

At a certain point, I found myself surrounded by beer cans, watching American Hoggers, and realizing that I needed to get off the couch and out of my boyfriend’s house. When a friend called and said their mom needed help at the family store, I jumped at the opportunity—not thinking much about the fact that the “family store” was a head shop, a place that sells paraphernalia for using drugs. I’d worked as a line cook in plenty of restaurants and as a guide at rafting companies, I told myself. What could be so different about working at a head shop?

The store occupied a vast brick building, formerly home to an auto shop. The display cases held a hodgepodge of merchandise—from switchblades to bongs, dildos to vape pens—lit poorly by an equally bizarre assortment of lamps and fluorescent lights. Mannequins wearing lingerie and T-shirts covered in stylized marijuana leaves hung from the vaulted ceiling.

On my first day on the job, a group of twentysomethings walked into the shop. One of the guys—clearly the leader—was covered in tattoos, some of them done in the distinctive prison stick-and-poke style. He swaggered around the store, the tendons in his forearm standing out as he gripped the front of his oversized jeans to keep them from sliding off his wiry frame. A chubby girl with dyed blue hair hung off his other arm. The group clustered in the back corner by the tattoo-kit display.

I awkwardly shifted my weight from foot to foot behind the counter as I considered whether I should approach the group and ask them if they needed help. Except for a penchant for cheap beer and some experimentation in college, I am not a drug user. I had no idea what half of the merchandise in the store was for.

The group by the tattoo kits seemed to have reached a consensus. The leader approached me and asked for help. He called me “lady,” which made me feel, at twenty-seven years old, hopelessly uncool and even more out of place. I sold them an assortment of tattoo needles and ink. As I was finishing ringing up their purchases, the blue-haired girl pointed to something in the display case below the register: an oil burner. “We need one of those, too,” she said.

The head shop staff called them “oil burners,” which was our code word for meth pipes. As I wrapped one of them in a brown paper bag, I felt my attitude towards the group change. Instead of feeling intimidated by their swagger, I felt superior. After all, I wasn’t the one covered in crappy prison tattoos buying a meth pipe.

As I was driving home after closing up the shop, though, my mood darkened. Working a ten-hour shift behind the counter had been a welcome respite from my recent routine. At home, I struggled to find ways to pass the time. I was alone for much of the day while my boyfriend was preoccupied with his projects. I spent hours scrolling through social media, reading headline after anxiety-inducing headline. When I couldn’t take it anymore, I tried to read, but could only manage a few paragraphs before my thoughts would return to the empty shelves in the supermarket and the pictures of unmarked coffins filling a mass grave in New York City.

A mutual friend came to visit for a few days. When there was a tornado warning, we sheltered in the neighbor’s business—a dog daycare, shuttered by the pandemic—while my boyfriend stayed at the house. The power went out, so we sat in the dark drinking cocktails. My friend asked if I was doing okay. I started crying.

For some reason, going to the head shop every day and selling oil burners, porn, and tattoo kits for $8 an hour gave me a sense of purpose. And the owner, a middle-aged British expatriate, clearly needed my help. She had recently gotten out of prison, and because of her parole arrangement, she wasn’t allowed to enter the main part of the store. I would unlock a side door for her each morning so she could enter her office, where she kept a stash of chips and imported British candy for employees to munch on during the day.

The owner called me “hun” and would text me during the week to check in and make sure I was doing okay. (“It’s a great day to be healthy, free, and happy,” one text read.) In case things were not okay, she had put a pink pellet gun in a drawer under the register.

One day the owner found a half-broken plexiglass sheet in one of her many piles in the storage room. She propped it up in front of the register as a makeshift protective barrier against the virus. There it remained for months, in spite of her promise to purchase a less broken and more effective solution.

After several days behind the counter, I adapted to my new environment. To hide how green I was, I acted casually nonchalant in response to all questions. Occasionally, I was asked if I sold drugs or knew anyone who did. (I always said no.) But for the most part, people were just looking for advice. Some customers wanted my opinion on the water pipe or bong they were considering. A few regulars would ask if the store had gotten any new porn DVDs. I helped a woman purchase her first sex toys—and then, when she called the store a few hours later, I explained how to use them. A Hells Angels member spent half an hour showing me pictures of his cat.

To fit in better, I came to work in black skinny jeans and combat boots, a black trucker hat pulled low over my eyes and my hair down. I started smoking cigarettes again. I also started becoming curious about my customers. I would try to guess what they were going to buy as soon as they walked through the door. Would they head for the tattoo kits? Make a beeline for the porn and sex stuff? Spend an hour selecting the perfect glass “tobacco” pipe?

One day, a man entered the store. He was at least six feet tall and looked like he could easily bench double my body weight. I found him handsome in a “gym rat, low-carb, protein powder” sort of way—handsome, that is, except for his lips, which had been chewed to shreds. I guessed that he would head for the sex stuff, in search of Crazy Rhino or some other male enhancement supplement. Or maybe he would get some poppers, an inhalant sold as a nail polish remover and said to increase pleasure during sex.

Instead, the man approached the counter and pointed to the oil burners in the display case. “I hate buying these things,” he said, staring at the floor as his face flushed with embarrassment.

“Yeah,” I replied, not really knowing what to say. I was surprised by the shame in his voice.

I reached into the display case and set the oil burner on the counter. “Hey, how do my lips look?” he abruptly asked me. “Do they look bad?”

I felt myself involuntarily grimace. “Yeah, they look pretty bad. You should probably go home after this.”

I carefully wrapped the oil burner in a paper bag as the man laid seven crumpled ones on the counter. Then I handed the bag to him around the broken plexiglass barrier.

From the front window, I watched the man climb into his pickup truck. It was a new truck with a lifted suspension, and I couldn’t figure out why someone with that kind of money—who worked out and obviously cared about his health—would also be a meth user. I wondered about what actually set me apart from this person in pain, someone clearly in the throes of a meth binge.

A few days later, I met Overalls and her boyfriend for the first time. Like most of my customers, I never learned this woman’s name, but I decided to call her “Overalls” because I never saw her wear anything else besides her faded denim overalls. She looked like she used to be thin but had recently filled out, and her body didn’t know where to put the new weight. Unlike many customers, she smiled with a full set of teeth. Overalls was always in motion—talking, laughing, flicking her dishwater-blonde hair over her shoulder. Her boyfriend was a back-alley tattoo artist. Quiet and scrawny, he had a habit of cupping his baseball cap with one hand to hide his eyes when he spoke, which was seldom. Overalls did the talking.

At our first meeting, Overalls walked up to the counter and started mumbling excitedly at me, her words slurred from whatever drug she was on. Her boyfriend stood bashfully a few feet behind her, hands in his pockets, staring at the floor. I’m not from the South and have a hard time with rural accents even when the speaker is sober, but I pieced together enough of her words to gather that her boyfriend needed a picture printed to use as a stencil for a tattoo.

Luckily for Overalls and her boyfriend, the store’s owner was in that day, and I was bored. I stepped into the back office and explained the situation to my boss. We spent the next forty-five minutes struggling with the printer and the wi-fi. I went back to the counter while the owner tried to troubleshoot the issue. Overalls kept up a steady stream of chatter as we waited. I eventually found myself sucked into a lively, if somewhat one-sided, conversation. She told me that the tattoo was going on someone’s forearm, showed me a tattoo of a flower on her shoulder—her boyfriend’s work—and recounted her conversation with the gas station clerk that morning.

Finally, the owner emerged from the back office with the printout. As it turned out, the boyfriend knew the owner’s ex from a prison stint. I watched her face light up at the mention of his name, and her usually brisk demeanor suddenly become warm and maternal. She seemed to genuinely care about the down-on-their-luck couple, whom I had been observing until then—I realized, guiltily—with a morbid curiosity.

At one point, Overalls’ boyfriend insisted that the owner’s ex still loved her. “I don’t think he wants anything to do with me anymore, hun,” she replied, her smile vanishing.

She held out the printout. “Will this work for you, dear?” she asked.

The boyfriend nodded.

“Take care of yourselves. Come back if you need anything else,” she said.

Back at home, my relationship with my boyfriend continued to deteriorate. Minor disagreements turned into long silences. Attempts to talk through our issues turned into slammed car doors and dramatic exits. I found myself becoming smaller and smaller—emotionally shut down and uncommunicative. My best friend told me to leave him, but I felt trapped by the circumstances of the pandemic and my ill-advised move across the country.

Over the next few weeks, Overalls and her boyfriend kept dropping by in their rusty Chevy Blazer, in search of printouts to use as tattoo stencils. I was beginning to realize that some of the store’s customers were giving back-alley tattoos to make the money they needed to buy drugs. Nevertheless, I looked forward to my conversations with Overalls. She always had a lot to say, though she careened wildly from subject to subject, never spending more than a few sentences—or, sometimes, even seconds—on a particular topic.

Her interactions with the gas station clerk were a common theme. “We were in there this morning, and she said that she could tell we were high!” she told me one day, her eyes widening with outrage.

“Yeah,” I said mildly.

“I mean … she didn’t have to say that,” she continued sullenly, clearly taking issue with the clerk’s accurate assessment.

Overalls was always animated and enthusiastic. Her appearances at the store brightened my mood amid everything that was going on at home. I realized that I genuinely liked Overalls as a person.

The twentysomething couple I’d met on my first day became regulars as well. The rail-thin man with the prison tattoos would pace the store like a caged tiger while the blue-haired woman bought tattoo supplies and oil burners. She was exceedingly polite, I noticed. One day, she was forty cents short. I let it slide, but she returned later that day to pay me back.

Eventually, Tennessee eased its lockdown restrictions, and I was able to return to my job as a kayak instructor. I stuck it out with my boyfriend for another month or so after that, but the pandemic had changed things between us. It had changed me, too, by bringing me face-to-face with people I’d looked down upon before. I never saw the man with the chewed lip again, but I still wonder about him. Since the pandemic began, the use of meth and other drugs appears to have soared across the country, along with drug overdoses.

I still think about Overalls from time to time, too. At some point, the store’s printer stopped working, and she stopped coming by. With more time, though, perhaps we would have become friends. I wonder where she’s printing her stencils these days, and if she’s still exclusively wearing overalls. Wherever she is, I hope she’s happy.

Lynn Barlow Lynn Barlow is a writer based in Asheville, North Carolina. When she’s not writing, she can be found skiing, whitewater kayaking, or playing fetch with her dog Urza. Instagram: @biggitygnar

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content