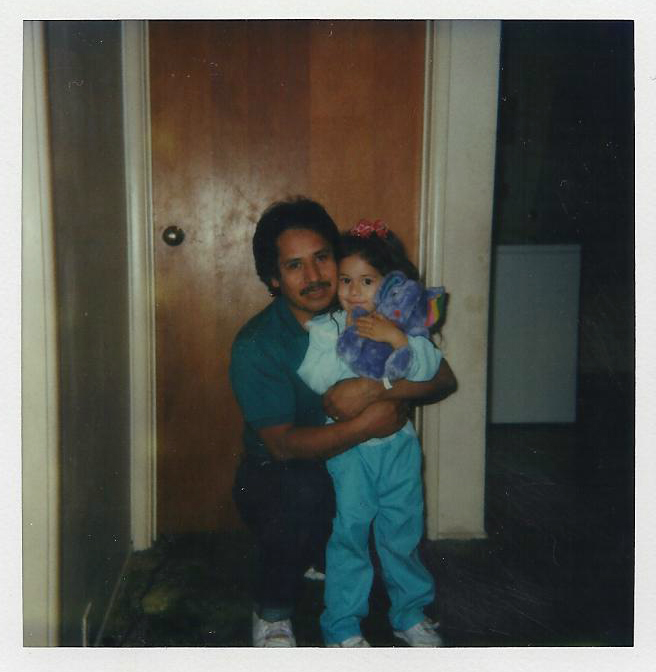

When I was growing up, I knew my father had become an American citizen around the time I was born in 1985. What I didn’t know was that until then he’d been living as an undocumented resident of the United States for more than twenty years. Never anxious to talk about this part of his life, my father simply didn’t volunteer the information.

When I was growing up, I knew my father had become an American citizen around the time I was born in 1985. What I didn’t know was that until then he’d been living as an undocumented resident of the United States for more than twenty years. Never anxious to talk about this part of his life, my father simply didn’t volunteer the information.

Like many children of immigrant parents, I was told story upon story that began, “When I came to this country…” But certain details of my father’s journey weren’t shared until I was twenty-six. Even after all these years, the story of how he emigrated from Mexico isn’t one my father likes to tell. He came from a generation where one’s citizenship status was something not to be discussed. I only learned of the specifics because I poked and prodded until he finally gave in, saying, “Tell my story when I’m dead.”

To people like my father, in spite of being an American citizen, these stories remain unsafe to talk about publicly. In the back of his mind is the lingering fear that telling his story will somehow get him deported. If not deported, then he will lose his job, or some other bad thing will happen. Silence and secrecy are my father’s only means of protection.

When I told my dad about the Dream 9, a group of undocumented activists who openly defied US immigration law in an act of civil disobedience last month, he told me a story he had never shared before. After being in the United States for five years, my dad reached a point where he’d had enough. He was always hungry, tired, and on the verge of homelessness. Working under the table without papers resulted in constant exploitation, and all he wanted was to go home to his family.

Without a dollar to his name, my father walked along the Los Angeles highway with his thumb out, hoping someone would give him a lift to San Diego so he could cross the border into Tijuana. Once he arrived, he planned to find a job and save enough money to return to his parents, who lived in the Southwestern Mexican state of Michoacán. But, as he puts it, fate intervened.

My dad walked along the interstate for an entire day, and not a single person stopped to give him a ride. Since it was the 1970s and hitchhiking in California was fairly common, my father (ironically) took the drivers’ unwillingness to pick up a poor, brown man as a sign that he wasn’t supposed to return to Mexico, after all. He resigned himself to whatever fate was keeping him in the US, and walked all the way back to LA. For the next fifteen years, my dad worked backbreaking jobs that kept him one paycheck away from homelessness, separated from every family member and friend he’d ever known.

It’s difficult for me to think about what my father’s life was like during those hardscrabble years, but still I ask him to tell me. He explains the ways he was able to scrape out a living in a country he felt didn’t want people like him and made it as hard as possible for them to survive.

When he shares his pain, I see my father differently than the angry, quiet man I associate with my childhood. My dad had every intention of living the American Dream, even after years passed and it remained out of reach. He’d wanted to be a doctor or an engineer, and to give my brothers and me opportunities that were never possible for him. Instead, each day was simply about surviving. My father worked hard as a janitor to support our family, but he and my mom were never able to climb out of poverty. There was no time for dream chasing, so my father acquiesced to a dream deferred.

As the Dream Act is adopted in various states and Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) allows undocumented youth to obtain driver’s licenses and work permits, I think of the adversities undocumented youth won’t face that my father had to overcome. I think of how the Dreamers, as they’ve come to be known, represent the unfulfilled desires of my father’s generation. So many of our parents secretly came to the United States, where they hid and were silent because to do otherwise would mean giving up what little they had for which they’d sacrificed everything. To them, immigration is not just a political issue; it is a life force that is brutal and beautiful, full of pain and of love.

My dad still struggles with using the term “undocumented.” For him, the word “illegal” comes much easier. He spent twenty years in a country where his existence was criminalized, and that feeling of not belonging isn’t something that “papers” can fix. My dad still behaves like that twenty-something kid who wasn’t protected under the law. He fears men in uniforms. He can’t speak out against those who treat him unfairly. He is constantly worried that everything he’s worked so hard for can be taken away in an instant.

When there is no ability for you to speak openly, no politicized community creating safe spaces, and no internet to connect you anonymously, you’re an island that internalizes what you’re told. The Dream 9 is helping my dad connect to his chosen country, to heal the hurts of its past abuse. Perhaps that is too much to ask from nine young people. But as they risk their own livelihoods for the sake of their communities, people like my father, whose lives have been steeped for so long in silence and in fear, are reading about their courage with tears in their eyes, in awe of a generation that refuses to hide in the shadows.

Tina Vasquez

Dear Reader,

In The Fray is a nonprofit staffed by volunteers. If you liked this piece, could you

please donate $10? If you want to help, you can also: