Some vows are better broken. When my maternal grandfather left Sicily as a 16-year-old boy to journey alone to America, he promised himself he would never return. He had grown up fatherless in a village along the rocky shore, and it held many unpleasant memories that he was eager to escape. He often told me that growing up, he had felt like an outsider, enduring uncles who excused their abuse and ill tempers for the sake of strengthening his character, and that he was happy to “never lay eyes on that place, or those people, again.” He certainly embraced no nostalgic feelings for his hometown, none that he admitted to, at least.

Four years ago, I had the opportunity to invite him to vacation in his small hometown of Castel di Tusa on the northern coast, with me, my husband, and my two sons. I tempted Pa by promising that he would fall asleep to the sound of the same Tyrrhenian surf that had crashed outside his window when he was a boy. I thought it would benefit him to return to the place where he had once felt underprivileged, now that he was a man with a rich life, a large family, and many accomplishments of which to be proud. After his initial knee-jerk refusal, with the help of some tender encouragement from his loved ones, he realized that he would like to see how things had changed after almost 70 years, and agreed to join us.

The bloodlines from both sides of my family tree originated from Castel di Tusa. Its founders were presumed to be refugees from the ancient city of Halaesa, Italy, founded in 403 B.C. by Archonides and later destroyed by the Arabs, and the ruins of previous eras are visible on a hill outside the town limits. Named for the walled 14th century castle, whose grounds the townspeople never saw, Castel di Tusa consisted of only four dozen or so houses which expectantly faced the harbor. The castle’s tower still stands and the nearby buildings in the center of town exude a medieval flavor even in the 21st century. The town itself fans out from the coast, with meandering lanes and alleyways with names like Via del Pesce, or Fish Way, and Strada de Café, or Coffee Street. I had visited in previous summers, when the streets were full with beachgoers, music, and dancing, and was thrilled by introductions made by my father’s sister to cousins, great-aunts, and great-uncles. In those encounters, I met several people who knew my grandfather and sent him their regards. So when we returned together, I brought Pa around to find the folks who had asked about him.

I knocked first on the door of one older woman who had been one of Pa’s close childhood friends. When Maria answered, my grandfather was standing several paces back.

Maria greeted me with enthusiasm, then quickly asked “And how is your nonno?”

“Why don’t you ask him yourself?” I said, stepping aside to reveal the 85-year-old man behind me.

Maria’s hand flew to her mouth in surprise, and then stayed there for a while, covering her neglected teeth in the face of Pa’s movie star smile. As they began to recall dear friends and old stories, she relaxed and forgot her self-consciousness. They were two young people again, reminiscing.

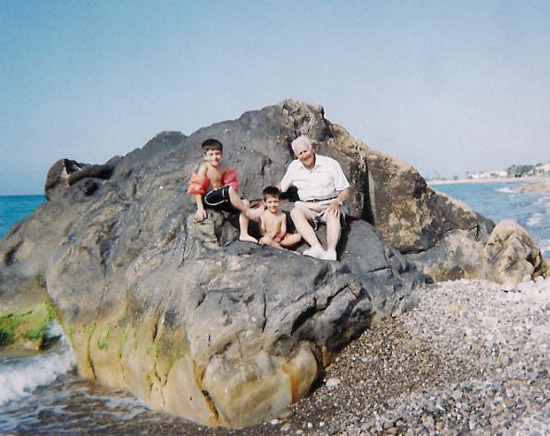

The town is quiet. Though electric streetlights now lent a soft glow to the evenings and houses currently stood where only trees had before, not too much of the scenery had changed. Pa’s former house was now four stories instead of one, and a low wall had been built between it and the sea. We could smell the fresh tang of the salty air and feel the pebbles on the beach shift under our feet as he undoubtedly had when he had cavorted with his young playmates. His favorite rock, to which he had gone for solace and contemplation, still stood at the water’s edge, and he climbed it with my sons.

“This rock used to be a lot cleaner when I lived here,” he joked. “Maybe we should scrub it, huh?”

The streets were now paved, in brick, no less, a result of restitution payments from the United States to Italy after World War II, but the piazzas still lay at the same intersections. Walking with Pa through the very squares he had frequented as a boy, I could picture him perched on a worn seat fashioned out of a log, intent on catching pieces of grown-up conversation. He pointed out to me the sites of his childhood stories: the railroad bridge festooned in red and purple bougainvillea where he had split open his knee while running home to dinner, the sheltered cove where his fishing boat had been anchored, and the dark tunnel where he and his friends once pulled a scandalous prank involving slippery prickly pear leaves and smelly outhouse pails. Sadly, Pa’s best friend had since passed away. However, we met the man’s son, and he recounted stories featuring my grandfather that his father had shared with him, and that made Pa’s eyes fill with tears.

Pa reacquainted himself with several relatives and spent the siesta hours either visiting or just roaming the steep streets on his own. He climbed stairs that at home would give him trouble, but he was reinvigorated there. As my grandfather told me of his afternoon’s adventures each evening, I could see his perceptions shifting, the tight stays of his defenses loosening. The warm reception he was receiving was like balm on the hurts he had held on to for over 60 years, and I was glad he had decided to make the journey.

I’m heading back to Castel di Tusa this fall with my family. Since our last visit, my grandfather has had one knee replaced, and the other, which he hasn’t yet addressed, has deteriorated further. He tires more easily now, and despite his friends’ entreaties to return, he won’t be joining us. I’ve promised to take gifts and good wishes with me, and that I’ll come back with video and photos. In doing so, I’ll be bringing him more than just images; I’ll be letting him find his hometown again.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content