It is 6:30 p.m. and the brash young comedy team the Illegals have only half an hour left before the women in the Russian hair salon kick them out. Half an hour is not a lot of time, they figure, but it’s enough to run through their comedy routine one more time.

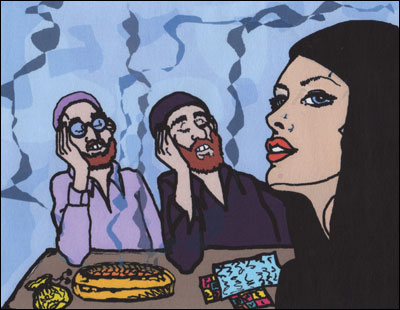

As the sound of an upbeat melody starts rolling, Semyon, Ruslan, Alexei, and Paul take two steps toward the mirror wall of the room, raise their arms, and smile smugly. Then they break into a flurry of short skits and absurdist one-liners, all in Russian.

“Do you have anything for the head?” Ruslan asks, looking pained, in one scene.

“Here, take an ear …” answers Alexei.

Looking in the mirror after every joke, the Illegals pretend to see the blinding stage lights and the cheering audience that will greet them in two weeks at the popular Russian comedy competition called KVN.

KVN, roughly translated as the “Club of Humor and Wit,” is a team game show, where students from different colleges, cities, and countries compete by presenting comedy sketches, humorous musical numbers, and improvisation. It is fast-paced and intense; one of the show’s creators once described it as “intellectual football.” With no direct equivalent in other cultures, KVN is an essential component of modern Russian life and a popular import of Russian-speaking immigrants around the world.

The fifty-year-old tradition started after the death of Stalin. As Soviet control began to ease in the late 1950s and 1960s and television sets became more common in Soviet households, a group of Russian university students created a unique television game show. At first, KVN was a question-and-answer game based on a Czechoslovakian show and similar to Western models. Although the teams had to give correct answers, witty answers were also allowed. Soon, the producers began to emphasize humor, making up amusing contests and assigning the teams funny skits to prepare.

With lightheartedness rarely seen at the time and humor normally reserved for the underground subculture, the nationally televised show immediately captured the Soviet imagination. During each game, life on the streets would cease, and the next day, everyone would discuss the jokes they’d heard. KVN aired through 1971, expanding to more and more teams from different cities and Soviet republics, but then was cancelled due to criticism from government officials. It was revived only at the dawn of glasnost, when emerging liberties and disarray in the government allowed for less control of what was being said on television.

A humorous critique of the world in the form of popular entertainment, KVN has continued almost unchanged since Soviet times. In Russia and other ex-Soviet republics, being a “KVNshik” can make one a celebrity on par with famous professional comedians. Away from its television audience, however, KVN is — for some 40,000 Russian-speaking immigrants in the US, Israel, Germany, and even Australia — not a road to fame, but a unique national tradition worth holding onto in a foreign land.

Looking in the mirror, the Illegals rehearse a scene from one of the three essential contests forming any KVN game, including the upcoming quarterfinals. Each game starts with the “Greeting,” where a team introduces itself with short tidbits of humor, loosely connected miniscenes, and dialogues. Then they move on to the “Warm-Up,” an improvisational contest in which each team has thirty seconds to come up with a funny answer to a question. Then comes the “Homework,” usually the longest and most theatrical part of the KVN game. It is akin to a sketch from Saturday Night Live and is rehearsed in advance. The Homework skit needs a lot of preparation, and each teammate has to be on top of his game.

For the Illegals, one of the key moments in the Homework is a scene borrowed from “Beauty and the Beast.” Ruslan — a blond, blue-eyed, big-boned Byelorussian — plays the merchant, whose three daughters (Paul, Alexei, and Semyon) ask him to bring back gifts.

“What would you like, my oldest daughter?” Ruslan asks.

“Bring me a decorated shawl,” replies the redheaded Paul, “from Gucci!”

“What would you like, my middle daughter?”

“Bring me an older sister who is not stupid,” says Alexei, the tallest of the three “daughters.”

“What would you like, my youngest daughter?”

“Bring me alimony for three years from that Beast!” answers Semyon, carefully enunciating every word.

At the end of the scene, everyone starts talking at once. Paul gets criticism for his bad pronunciation of “Gucci.” He repeats it several times, giving more punch to the “cci.” Semyon blushes deeply as he tries to argue with Ruslan about the wording of the skit. Meanwhile, twenty-five-year-old Alexei — the team’s oldest member — smiles to himself like a satiated cat. His hair is sticking out and worn-out jeans hang on his tall, thin body. Over the clamor, he hears Sasha, the team’s music assistant and only man behind the scenes, scolding Ruslan.

“You show off too much,” Sasha says. “And you eat up lots of words.”

“He is fine, leave him alone!” says Alexei protectively. Putting his hand on Ruslan’s shoulder, he tells him, “You are a star.”

Other, less poignant criticism continues to echo through the room as everyone gets ready to leave. Ruslan, who has the springy walk of a boxer and a childish smile, tells the skinny, stylishly dressed Paul that he does not like him as an actor. “Do you like me as a man?” Paul says flirtatiously as everyone chuckles.

“Bunch of homos on this team!” says the dour KVNshik as he walks out into the cold Brooklyn night.

The Illegals, whose four members currently live in three states — New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania – are a truly heterogeneous team. Unlike the majority of Russians who immigrated as Jewish refugees, Ruslan and Alexei both moved to the US three years ago, using a four-month visitor exchange program to stay on the new continent. Before the two friends met, Alexei and a few other young illegal immigrants created a KVN team based in New Jersey and named it, appropriately, the Illegals. At first, many KVNshiks, who have lived in the US since the biggest wave of Russian immigration in the early 1990s, thought the laid-back style of the Illegals was strange. Others, however, saw in their style a way to improve KVN’s American league.

“I first met them at the KVN festival in 2003,” remembers Sergei, a member of a Chicago team and a friend of the Illegals. “They brought freshness and youthful inspiration into the game. I immediately wanted to meet them. Their acting ability and quality of humor put them on a level higher than the other teams in the league.”

Yet so far, the Illegals have not been very successful. They left their first game due to disagreements about the judging. Then, they regrouped to incorporate some members of a team from Philadelphia — Semyon and Paul among them.

Semyon, who has attentive eyes and an apologetic manner of speaking, did not participate in KVN back in Russia, but loved to watch the games on TV. Unlike Alexei and Ruslan, he is not an illegal immigrant. After he moved to Philadelphia with his parents five years ago, he found out about the local league and created his own KVN team. “I wanted artistic realization,” he explains. “Some people paint, others play a musical instrument, and I play KVN. It’s a great feeling when you’ve written something, performed it, and the audience liked it. I feel artistic satisfaction.”

Semyon invited his childhood friend and neighbor, the redheaded Paul, to join the team. Paul, who had just moved from Israel, did not remember much Russian. But he was stylish and funny and had a good attitude. “I basically came to KVN for sex,” Paul says impishly. “But now I am the one who has to supply all the chicks.” Outside of KVN, Semyon and Paul work and go to college. They are majoring in film and hope to make a documentary about the plight of young illegal students like their teammates.

The last member to join the Illegals was Ruslan. Although he contributed professional KVN experience from Russia, the team still lost last season’s semifinals. “I went to rehearsals like a fool with a notebook and a pen,” says Ruslan. “And everything just ended in drinking.” Although Alexei’s official response to Ruslan’s complaint is “Nothing brings people together like vodka,” he blames their loss on razdolbaistvo — a slang word that means irresponsibility, carelessness, and even laziness.

“Razdolbaistvo is both our flaw and our style,” he says. “We can’t get together, we can’t rehearse, we can’t figure out the music. That’s why we lost at the semifinals last year. We were funny, but unorganized.”

Less than two weeks before the game, Ruslan is having breakfast with Alexei at a Russian restaurant in Brooklyn. A rowdy group of men drink vodka and argue about yesterday’s hockey game. It is noon. As they wait for a steak, chicken livers, and apple blintzes, Ruslan explains that he has been playing KVN since he was thirteen.

“I even remember the first joke I had to say,” he says, his blue eyes gleaming. “We had this scene: an ad for Aeroflot. The guy looked out the window and said ‘Oh, look, flying elephants.’ And I took his glass away and said ‘Okay, that’s enough for you.’”

“You ripped!” says Alexei mockingly as he digs into his steak.

“When I first started, I didn’t write my own jokes and didn’t really act onstage,” continues Ruslan. “I learned how to write jokes, how to feel the text. So, KVN is not about talent, but experience.”

“I had talent, but I’ve killed it working with these guys,” says Alexei with a sigh. “People told me to go into acting.”

“Well, people told me that, too,” says Ruslan defensively.

“No, no, they lied. Besides, I was the one who told you that. Anyway, I didn’t want to go to acting school, because I like it as a hobby, not as a profession. I’ve always played the role of a fool, and an actor is more than just one character of a fool. My first role ever was to play a fool, and then the second, and the third, and it stuck. But I sort of act like a fool in life, too. Maybe that’s why this role is easier for me.”

Alexei, who became a KVNshik when he entered university in Russia, thinks he should quit competing after this season. “This game is for the young,” says the twenty-five-year-old. “I need to quit soon. I am way too old and KVN takes away so much time.”

“It takes away health, too, since we need to drink a lot,” interrupts Ruslan.

“Time and nerves,” finishes Alexei, who goes to college and keeps a night job at a Russian TV station.

“A great classic once said that KVN is not a game, it’s a lifestyle. Of course, no one knows what that means, but it sounds beautiful,” says Ruslan. He turns more serious and adds, “Someone who once participated in the games, I mean like fully — writing, acting, and stuff — cannot just quit.”

But Alexei doesn’t want to dwell on the serious. “Anyway, to come back to talking about talent,” he says. “Me and him play pretty much all the roles. Wait, what the hell do those two do?”

“Well, one is a redhead, so if something goes wrong, we can always blame him.”

“He also makes great tea.”

“Yeah. And the other one, Semyon, he is just a nice Jewish boy who doesn’t do much.”

“Every team needs to have one, you know,” concludes Alexei.

In Russia and many former Soviet nations, every KVNshik nurtures the hope of becoming a celebrity. But in the US, where an independent KVN league started ten years ago, stardom is out of the question. Although in format and style the American KVN league mirrors the High league of Russia, it does not have millions of fans. The teams sponsor themselves, auditoriums rarely fill up to capacity, and only a few KVN games make it onto a local Russian TV channel.

However, the enthusiasm of local KVNshiks like the Illegals makes them stand out among the mass of Russian immigrants. They do not resemble the majority of older Russian Americans, who, having left the old country for good, severed all ties with modern Russia. They are also not like many younger Russians, who grew up in the US and know little about their country of origin.

Instead, the comedians grew up in the post-Soviet Russia of endless possibilities. They emigrated not because they had to, but because they could. They are media-savvy children of globalization — in their spare time, they browse Russian websites and watch Russian satellite TV. Unlike some immigrants who are completely detached from the life of a cold country thousands of miles away, young KVNshiks often exist in a strange niche between here and there. On the one hand, they have Russian friends, Russian wives, Russian vodka. On the other, they are integrated in American society — they graduate from schools like Harvard, Berkeley, and NYU and work as programmers, businessmen, or lawyers.

But living in this niche, American KVNshiks find themselves at a disadvantage. Surrounded by a different culture, they have neither the structural and financial support enjoyed by Russia’s nationally televised KVN, nor the possibility to achieve true stardom as Russian-speaking comedians. Even their humor reflects their unique situation. To entertain their small, immigrant audiences, they often turn to localized jokes about the immigrant experience, be it Brooklyn restaurants or linguistic mix-ups.

When he first saw American KVN, Alexei thought it was very amateur. “Three years ago it was just horrible,” he says. “The favorite theme was when a dude dressed up like a woman, came out onstage, and said something. The first time I saw that, I realized that you can’t perform here. But everything has been changing and looking more like the real thing. If there are no young teams who want to compete, there can be no KVN. What would be left are the older teams. They are nice guys and their humor may be fine for this audience, but they are not helping KVN evolve. We need more young teams, especially guys from back home.”

With their experience from “back home,” the Illegals are trying to raise the level of the American league by bringing humor that is both poignant and not immigrant-specific. Their other choice would be to give up KVN completely. But even with this amateur league and a limited audience, playing KVN is worth their time. It is a tradition, a form of identity, and a way to preserve their culture.

“We can spend a whole evening talking about KVN and not even notice it,” says Alexei. “It has become part of our lifestyle.”

At 11 p.m. on a Thursday, Alexei is working the controls at the Russian TV station. With little time left before the game, he is surprisingly calm.

“We still have a lot to work on, and we only have one day left — that’s definitely a big minus,” he says. “At the same time, we are funny dudes, we look cool onstage, and we are pretty good actors. I don’t remember a game when we totally rehearsed. If one joke doesn’t get through to the audience and then the second, people see that the team did not rehearse. But if the first joke gets to them and the second, then the audience is in the right mood, they clap and cheer and don’t pay attention to the little mishaps, because everything is absorbed by the overall atmosphere.”

His deep voice leaves the hope for that magic atmosphere lingering in the empty control room. “Even though we are jerk-offs, everyone still wants to win. We all have problems, work, school, some of us have both work and school, not enough time, but you gotta have more in life than work or school.”

Alexei wants to win this season because he is not sure the Illegals will play next year. It’s not only his age. He is also worried that Ruslan may go back to Belarus. Although he has just received his work permit, Ruslan is waiting for a travel visa to see his friends and parents back home. For now, he refuses to buy a car, because he doesn’t want “to get anything that would tie me to the US.” If he does not get the visa before the end of the year, he will leave the country for good. At least in Belarus, Ruslan — the kind of person who sees the world “as if it’s made up of punch lines” — has a bigger chance of becoming a real KVN star.

Two nights later, there is commotion outside the dressing rooms of the Jewish Community Center in Philadelphia. Leather-clad Russian men smelling of liquor swagger down the hall, with Russian women in short skirts and heavy makeup trotting behind them. The women smile confidently, leaving a trail of sweet perfume.

Two women come back to the green room of the Illegals, with cigarettes and cans of Red Bull for the teammates. Semyon and Alexei open the cans and drink. All four Illegals put on hip, dark-gray jackets, beige slacks, and bright-colored shirts. The female admirers straighten out the men’s jackets and put gel in their hair. With only a half hour left before the game, the room is tense. There are endless bottles of cognac and juice on a table surrounded by drinking visitors. Semyon is angry and nervous because Ruslan has been drinking heavily.

“I’m gonna kill that fucker!” he yells. “How can he do this? The game is about to start! Where the fuck did he go?!”

Someone walks into the dressing room and asks, “Why do you guys look so gloomy?”

“Why should we be happy if we’re losing?” says Alexei, half to himself. He circles the room, muttering his lines and squinting nearsightedly. Sergei from the Chicago team tries to rally him. “Capture the audience, this scene is totally on you. If you capture the audience, you’ll rule, I promise you!”

Alexei nods absentmindedly, but does not speak. Ruslan comes back. He does not seem very drunk. “I’m always nervous before the game,” he confesses. “But when the fanfares sound, it goes away.”

Five minutes before the start of the game, the Illegals gather in a tight circle, put their hands together in the center, and yell in chorus, “We swear to you, O goalkeeper, that we will never lose!” They jump up, screaming and making punching gestures.

“I’ll destroy everyone!” bellows Alexei.

The female fans line up to kiss the teammates and wish them luck. An entire minute is filled with a seemingly endless “mma, good luck, thanks, mma, good luck, thanks …”

“It’s like we’re leaving for war,” Semyon says.

The auditorium is almost full. There are no empty seats, someone jokes, just unsold tickets. E. Kaminskiy, an experienced KVNshik from a legendary Russian team of the late 1980s, hosts the game. The jury, consisting of older KVNshiks, two of last year’s champions, and a TV newscaster (the only woman), sit in the first row. Five teams are competing tonight: NYU (famous for winning ten years ago), ASA College (famous for ever-changing members), the Philadelphia team (famous for attractive members), Nantucket (famous for constant intoxication), and the Illegals (famous for razdolbaistvo).

The game starts with the Greeting. “The Greeting is a chance to conquer the audience,” Sergei notes. “It’s all psychological. You need to click with the audience from the first phrase, with your energy and charm. If the audience reacts to you, then you’re the king.”

In order to pack in many disconnected jokes into the fast-paced Greeting, KVNshiks often imitate the format of TV ads, with their spicy one-liners. When the Illegals take the stage, Alexei announces, “American masochists ask to increase the punishment … for masochism in America!” The young audience is quiet. They process the joke. Then, they erupt in laughter. In another scene, Ruslan (who likes “current” jokes) plays Alexander Lukashenko, the Byelorussian president. After he won the elections, he says, “Dick Cheney called to congratulate me. He invited me to go hunting …”

After the Greeting, the Illegals are in third place. But this is no time for distress. They have to prepare themselves for the improvisational Warm-Up — what Alexei calls the most telling contest in KVN, as it allows the participants to show off their true ability in spontaneous comedy. With only half a minute to think, the teams have to answer each question as wittily as possible.

“In the last Winter Olympic Games, the athletes from Zimbabwe did not win any gold medals. Why?” reads out Kaminskiy.

The Illegals stand in a circle, whispering, laughing, and nodding. Finally, Ruslan approaches the microphone. “That’s because in the last Summer Olympics, Zimbabwe’s diver died of happiness when he finally saw water!” The audience cheers loudly — nothing like a bit of dark humor to please the Russians. After several questions, the judges once again reveal the score for each team. The Illegals move up to first place.

The next and last contest is the Homework. The Illegals have constructed their Homework performance around the childhood of each of the four members. First, Semyon announces that when he was a kid, he wanted to be a banker. In the bank, Semyon offers his customer (Ruslan) a $100,000 credit line.

“A hundred thousand?!” cries Ruslan. To the music from Pulp Fiction, he pulls out a gun and points it at Semyon. “Attention, everyone, this is a robbery!” He turns to Alexei, another customer at the bank. “Don’t move!” he yells. “Or I’ll shoot his brains out!”

“You are bluffing,” says Alexei, calmly.

“Why the hell am I bluffing?!”

“Because he doesn’t have any brains.”

After Semyon is dead, Alexei flees the bank and Ruslan hides from the cops under Kaminsky’s podium, where he finds “a remote control for the judges.” Suddenly, a newscaster — also played by Alexei — interrupts with “breaking news from the scene of the robbery.” Ruslan, it turns out, is a correspondent sent to cover the robbery he has just committed. Smugly, Ruslan says that no one has seen anything. “There is only one witness,” he says, pointing the gun at KVN’s host in the corner. “But he didn’t see anything, either.”

In the next scene, Paul comes out onstage to confess that he always wanted to be “a tall, broad-shouldered blond,” rather than a skinny redhead. At least he has acting talent, he says, and the Illegals break into the scene from “Beauty and the Beast.”

The final scene is from the childhood of Alexei and Ruslan — two thickheaded thugs.

“I can read thoughts,” says Alexei.

“People’s thoughts?” asks Ruslan.

“Yeah, people’s … c’mon, help me out!”

Ruslan raises a cardboard sign and Alexei proceeds to read it. “Thoughts,” the sign says.

When Ruslan ends up robbing Alexei, Paul and Semyon emerge in police uniforms and arrest them.

“And that is how we all met,” concludes Ruslan, as they take a bow.

Tonight, there is nothing stopping the Illegals. They have the charm and the energy, and they are prepared. The audience loves them. Most importantly, the judges love them. Tonight, the Illegals finally win.

Now, they only need to survive the after-party.

Update, August 3, 2013: Edited and moved story from our old site to the current one.

Sasha Vasilyuk Sasha Vasilyuk is a writer based in New York City. She was born during a cold Russian winter and grew up in the golden hills of the San Francisco Bay Area. Her essays and articles on art, culture, business, travel, and love have been published in the Los Angeles Times, San Francisco Chronicle, Russian Newsweek, Oakland Tribune, and Flower magazine. She received the 2013 North American Travel Journalists Association silver medal for her Los Angeles Times cover photo "Barra De Valizas." She is currently working on a collection of essays about her year-long solo journey around the world.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

Detroit’s transition from past to present.

Detroit’s transition from past to present.

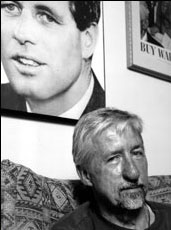

A conversation with Tom Hayden on being stirred by bullies and killers.

A conversation with Tom Hayden on being stirred by bullies and killers.

Explorations of history and heroism in London.

Explorations of history and heroism in London.