A heavyset man plops down on the bench. He wears the boots of a construction worker and carries a paper sack. The black bird circles around like he’s waiting to see what’s for lunch before he decides to land.

“This is a very nice park,” I say. “Do you come here often?”

He swallows his bite. “Only come because my job is here, but we’ll move on soon.” Across Aldersgate Street, adjacent to the park, a tall building is either going up or being renovated. It’s hard to tell.

I try to dig up some polite conversation, but only draw a blank, so we stare out from the loggia at the bird staring back at us.

“Know why this is called Postman’s Park?” the man asks. I shake my head no. “The General Post Office used to be over there,” he waves his hand in the general direction, “and the postmen would eat their lunches here.” I jot this down in my notebook. “Are you a writer?”

I say yes, and he launches into an interesting, if subjective, history lesson about the ancient Roman burial ground just beneath our feet and the divine experience John Wesley had across the street that led him to found the Methodist church. He keeps glancing at me to see if I’m writing all of this down. I am, but it’s with a grain of salt. Taking notes while someone is talking can be like turning a camera on him; it gives him license to exaggerate. If his stories are true (and as it turns out, they are) perhaps Watts knew this patch of land had a spiritual energy perfect to commemorate examples of ordinary citizens’ uncommon valor.

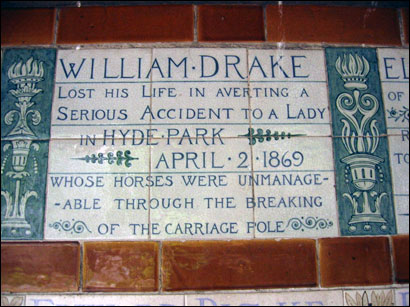

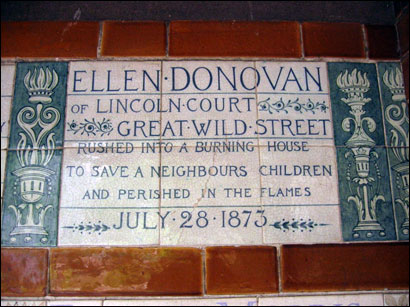

Philanthropy was foremost in Watts’ mind. Even in his artwork, he centered on “painting for others, either in his own times or in posterity, rather than for himself,” wrote Dr. Jacqueline Banerjee, an expert on the Victorian era. This constant outward focus may be what prompted the lukewarm Pall Mall Gazette review of a Watts painting in 1892, “But somehow it just fails to be either quite real or quite symbolical…” He eventually accomplished both; not in a world-class museum, but in a series of uncomplicated ceramic tiles. Rather than erecting an engraved marble slab where one name blends into the next, each person’s heroic deed is here to be remembered for all time. It is a gift of eternal validation, something we each long for so that we know our efforts haven’t been in vain.

In a city so entwined with the extravagance of its monarchy, I am happy to report I found in this little spit of a park the charitable spirit and tenacity of everyday Londoners. I also learned there are giants among us — men and women who embody the best each person has to offer. Perhaps we shouldn’t need monuments to commemorate that which we are all capable of. An inscription in St. Paul’s Cathedral, dedicated to architect Christopher Wren, says it best, “Reader, if you seek a memorial, look around you.”

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

Explorations of history and heroism in London.

Explorations of history and heroism in London.