“Inhale inspiration/exhale wonder/remember Right Now is all you have/constantly ask yourself/How can I make this now/The best now it could possibly be.”

-Christopher Johnson, “All I have in life is right now”

On an overcast and drizzly morning in late March, I found myself back at my alma mater, sitting through a five-hour conference with a roomful of people I didn’t even know. Still, we ended up having much more in common than I could have ever imagined. Plus, it was our chance to motivate one another to keep fighting against the never-ending pestilence called discrimination.

At that point in time, all I wanted was answers. I wanted to know what was being done about one of the most common, overlooked, and worst forms of discrimination that could ever exist.

Like all good journeys, it was going to take some serious probing out there in the world, and inside of me, to get anywhere with this, as I would soon find out.

Making some noise

At first, I was looking for a large movement or an ongoing demonstration with the whole nine yards: megaphones and marches to rattle everyone awake in the neighborhoods, and large poster boards screaming, “Let’s end the war among brothers” or “It’s time to love the diversity in diversity.”

That fantasy was crushed once my disappointing two-hour Google search ended. Even though I did come across several blog entries and essays from other people who had gone through the same thing as I did or even worse, there was still nothing MAJOR being done about it.

So I set my sights on the next best thing: on-campus advocacy groups. I’ve always heard they were a good resource for students that want to get involved and be informed on social issues, and I knew just where to go.

It felt strange calling up the Unity Center at Rhode Island College since I never did when I was there as a student. Ironically enough, it was the first place that came to mind, and I figured it wouldn’t hurt to try.

As I dialed the number to speak with Director Antoinette Gomes, I wondered what I was getting myself into. But it was too late to back out once she answered the call.

I was nervous, but got to the point. “Good afternoon, my name is LuzJennifer Martinez. I’m a freelance writer and alumni of Rhode Island College. I was looking to see if there is a group, event, or movement that the Unity Center knows of that addresses the issue of intra-racism.”

“I’m sorry, what?”

My heart sank. Was she offended already? Who did I think I was, mentioning something so negative to the director of the Unity Center, a group which focuses on bringing people together, not on what keeps them apart?

I didn’t think the term would be so loud and full of such weight when I said it, but it was like a crack of thunder just outside the window.

“Intra-racism. When people within an ethnic group or race discriminate against each other.”

“Yes, we come across that issue a lot and although there aren’t any specific events or groups to address it, there are some things going on,” she said.

Oh! Her response wasn’t incredulous; she just hadn’t heard what I had said. As a matter of fact, she didn’t even sound angry; she seemed to be thinking about what I was telling her.

The following night, Gomes said they were going to be showing a Neo-African film about the new narrative of being African American.

She also told me the Unity Center holds a diversity week on-campus every October, which I remembered from when I was an undergrad. “There’s a student organization on campus called L.I.F.E., which stands for Live, Inspire, Fight, Educate. I can give you their contact information if you’d like,” she added.

A week later I dialed the number L.I.F.E President Mariama Kurbally had forwarded to me through email, feeling much more confident than before. She explained that while the organization focuses on diversity as a whole, it does consider “the different parts to it.”

There are aspects like race relations (or “brown” and “black” relationships), that make diversity far more than just a “black” or “white” issue. She agreed with Gomes by saying that in many of the discussions and events hosted by L.I.F.E., intra-racism is always mentioned.

“Next month, we’re having our Diversity is a way of L.I.F.E conference, where we host sessions rather than one big convention. We usually talk about gender oppression, defining racism and intra-racism, to give people the tools to deal with it,” she continued.

Kurbally said she would get in touch as soon as everything was worked out, and I couldn’t wait to find out more about it.

From writer to attendee

The next thing I knew, I was sitting at the first focus group planning meeting of the conference at the Rhode Island College Student Union with a pen and notepad handy. Aside from meeting both Kurbally and Gomes in person, I got a better sense of what L.I.F.E was all about.

The organization was founded by Kurbally in 2008 with the mission to “promote individual development and improve the overall quality of life in a multicultural community,” by “giving its members a holistic understanding of pertinent social issues, empowering individuals through education, increasing awareness, and striving to create strong leaders within our communities from various backgrounds.”

I also met some of L.I.F.E.’s other officers and supporters. There was Vice President Malinda Bridges, Secretary Sandra Chevalier, Anthony Bailey, one of the conference presenters, and lastly, an L.I.F.E. member and R.I.C. undergraduate student whom, if I’m not mistaken, I remember being called “Tunde.”

Everyone sat at a square table, discussing details of the event like what time one information session would be held over the other and which activities to include throughout the conference. Kurbally filled in a tentative schedule on the dry erase board in the room, while I scribbled away on my yellow notepad.

I also found out that there would be a full one- hour session exclusively about intra-racism and it was all I could do to stop myself from grinning pathetically at the paper in front of me. About 10 minutes later, Hannah Resseger, a local spoken word poet and Rhode Island College graduate, walked in with Christopher Johnson and his daughter.

Johnson, another spoken word artist, was scheduled to perform his poetry during the conference and the conversation shifted into how he would go about it within the available time frame. In the end, some of the details were still not finalized, and the discussion shifted on to how the conference would be announced to the public. But before that, Kurbally asked us for some feedback.

“Does anyone else have any input? How about you guys, did you have any questions?”

She was talking to those of us who hadn’t said a word up until that point, but the comment still caught me by surprise. When she looked at me, I shook my head and looked down at my yellow pad. I felt bad for seeming indifferent, but I didn’t want to interfere since this was their conference.

I thought my job was to reflect back on how the event would address an issue of diversity like intra-racism. Yet, seeing the interest in what I had to say made me realize this was going to be different.

It was going to take more than just note-taking and listening; I was going to have to put down my pen and paper and get involved.

Finding common ground in diversity

The conference was scheduled to begin at nine a.m. in the Alger Hall building on the Rhode Island College campus with a breakfast and check-in. I arrived at 10:30 a.m., promising myself not to write a single word down until after the event. Thinking I would be able to quietly slip in without being noticed, I found myself waiting outside the electronically locked door of the high-tech classroom everyone was gathered in.

While I stood there hoping for someone to notice me, I felt like a student who was late for class and had missed the most important part of the lecture. The feeling intensified when I plopped down into a blue chair to join the circle of about 35 people with name tags stuck to their shirts.

They weren’t all college students either. There was a mix of parents, working adult professionals, high school students, and even a couple of professors I recognized from around campus not too long ago.

Everyone was sharing their impressions about some images they had just seen on a large screen depicting acts of hate throughout history. It was part of the first presentation of the day, from Rhode Island College alum Anthony Bailey, called “Connecting to Difference.”

I had arrived just in time for the final interactive activity, which brought us all to our hands and knees. We had 10 minutes to write out our answers to 15 personal assessment questions on large poster size sheets in black marker.

After that, we were told to hang them up along the walls and boards of the spacious room. Once I got the separate ditto with the questions, I huddled down over the large paper on the floor.

By the time I looked up from my answers, most of the walls were already covered so I settled for one of the easels lined up on one side of the room.

Bailey surveyed the rows of papers with different handwriting taped to the wall.

When we finished, he said, “Now I want you all to go around and silently read the answers from as many other people as you can, except your own. When you read a statement or answer that you agree with, put a check mark and your initials next to it.”

We made our rounds, with everyone’s shoes shuffling slightly as we moved from paper to paper. You could hear muffled whispers buzzing in the air.

“Oops, sorry!”

“Here, you can read it now, I’m done.”

All along, I was preparing myself for the sight of my paper with nothing but the answers I had written. I eventually started focusing on the responses from the other posters and found some statements I related to.

I love GOD and my family, check, JM.

I like learning from other people, check, JM.

I want to make a difference in the world, check, JM.

Soon it was time to read our own papers again, and I was shocked to find a modest sprinkle of checks, initials, and even smiley faces on mine.

We all returned to our seats in the circle so Bailey could conclude his presentation.

“Even though we are all different, we harbor similarities, and that’s how we can connect to one another,” he said.

Memories, rhymes, and tears

James Montford, Director of the Bannister Art Gallery at Rhode Island College, was next in line to present a session. But before that, Hannah Resseger popped up out of her seat and made her way to the center of the circle to recite a poem.

She stood quiet for a second before hurling into an emotionally charged performance that answered the timeless question, “Who am I?” Throughout the introspective narrative, you could feel Resseger fighting as a performer and protagonist against the preconceived labels inflicted on her by others.

It perfectly depicted the inner turmoil of when you are told who you are as a person of a particular group or culture, even if you don’t relate to it. I sat enthralled, watching Resseger’s afflicted enunciations and animated expressions as she jumped from identity to identity in despair, anger, and resignation.

All the while, I re-lived the indirect accusations of how I was neither American enough to pursue my independent ventures nor Puerto Rican enough to be passionate about what was rightfully mine.

I bit my lip but couldn’t stop my eyes from welling over. Montford sat almost directly across from me on the other side of the circle and his face blurred for several seconds.

I looked away in embarrassment, feeling surprised and frustrated I had reacted that way. But I wasn’t the only one who would be emotionally moved at the conference.

Montford’s “When You Feel Difference” session began with some group sharing. To the people who were sitting to his right, he said, “I want you to tell us your earliest memory of when you first felt different.”

A Hispanic teen described how when he was little and newly arrived from his country of origin, he sat in class one day feeling very sick and was unable to tell the teacher in time because of the language barrier.

When it was her turn to speak, a young Latina woman started describing something about her childhood but was so soft-spoken I couldn’t hear her.

As soon as she shared her memory, she burst into tears and remained visibly upset for about five minutes. I couldn’t stop looking at her, and wondered what it was that had affected her so much throughout her life.

When there were about 4 people ahead of me to speak, Montford reversed the directions of the activity. He asked the people sitting to his left and on to describe their most recent memory of when they felt different.

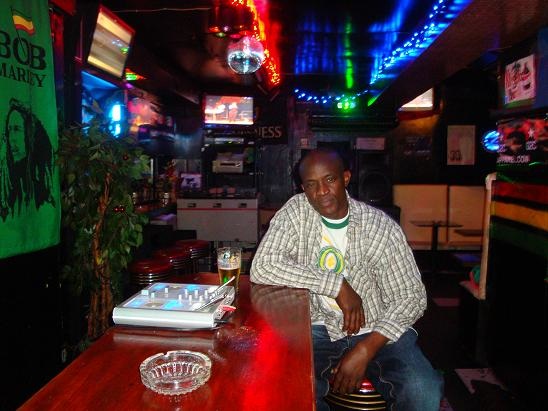

A young couple next to me said they felt different being the only ones married among their peers. Just a couple of chairs to my left, Christopher Johnson replied that he didn’t really have an example of recently feeling different because he has always considered himself to be so.

“I think that if I didn’t feel different, I wouldn’t feel right. Who wants to be all the same? I like being unique and being me,” he said.

Jay Chattelle, another spoken word artist who runs the Rhode Island Poets (RIP) venue with Johnson shared another perspective with the group. He said being at the conference was his most recent experience of feeling different because he couldn’t relate to everyone else’s perceptions on what difference was all about.

In a response to an email that I sent him after the conference, Chattelle gave some more insight as to what he meant by his comments that day.

“Being different to me is recognizing we are all the same. With everyone’s erg (sic) to be different and stand out, it’s a shame when we are the ones not taking responsibility for our actions. We are the ones that have to make change and we should start with ourselves,” he said.

At the conference, Rhode Island College Professor of Anthropology Carolyn Fluehr-Lobban also made a good point. She said we were taking action by simply being there to educate ourselves to be aware of diversity in our lives, as well as by learning from others and sharing our experiences.

“We are taking the time to be here and address it,” she said.

The power of words

After lunch, everyone settled in for some more poetry, this time from Christopher Johnson. As soon as he started, I couldn’t believe how fast he recited the intricate lines and wondered if he was free styling or had written it all down before hand.

He performed about 5 poems that all flowed beautifully to create different sentiments and tones. One of them called “Two angels” had a strong walk-a-mile-in-their-shoes effect and another one called “All I have in life is right now” was full of some refreshing philosophical insight. Of all the poems, the second one spoke directly to me the most, especially about discrimination and how to approach it:

“A friend of mine once told me/”there are a plethora of personality types in the world/One fact of life/meeting assholes is unavoidable”/Assholes have one purpose, to shit/they will shit on you with no regard simply because that’s who they are/But an asshole is positioned low on the body/meaning you have to be lower than an asshole to be shit on by one/so the trick to avoid being shit on/ is to never allow yourself to be lower than the asshole…”

As the words flung out of Johnson toward the audience, the message hit me in the face like a cup of cold water. Of course! The key to attacking discrimination is to remain above it so it can never attack you. What the poem said to me was that nothing would ever be solved if you allow yourself to be “lower than the asshole” by either discriminating back or being submissive to it.

And sadly, the problem will always be around since we are bound to encounter assholes, as Johnson said. But we can make the most of now by deciding to stand up and fight against it through awareness and empowerment. The poetic explosion continued with Resseger, who recited another poem called “Matriarch.”

Again, her interpretation had a theatrical element to it, where Resseger took on the burden and pain of the protagonist and channeled it through every word and line. It was the perfect segue into the next presentation from Rhode Island College Psychologist Dr. Saeromi Kim, where we got to tap into the root of our feelings about bias and discrimination and how we react to it.

The majority of Dr. Kim’s “Emotions” session not only made us aware of the different feelings we encounter during moments of conflict or prejudice, it gave us an idea of the triggers which can bring them to life.

Kim even took it a step further by making us aware of the internal biases we harbor within ourselves and how they develop. We participated in an exercise called “both/and,” where we referred to one personal characteristic and then acknowledged its opposite or conflicting pair through a sentence.

Kim explained how that can keep you from focusing solely on one aspect of yourself, which eventually causes you to discriminate against the other. She wrote out an example in dark red ink on an easel.

“I am both ashamed of the privilege I’ve had when I was growing up and proud of what I accomplished on my own,” she said.

Soon after Kim insightful presentation, we all got into an interesting discussion lead by Anthony Bailey about “understanding privilege.” By then, the group had shrunk considerably, which only made the conversation more intimate and candid. We discussed what the term ‘privilege’ means and eventually concluded it all depends on how you look at it.

The concept can either have a positive or negative connotation to it, which, therefore, makes it a diverse and complex issue in itself.

Speaking out

It was just after two p.m. when it finally sunk in just how long we had been there. My eyes were getting pierced by the artificial brightness in the room and my legs hurt from crossing them so much.

And when would the intra-racism session start? While we were waiting for the next presentation, I tapped Bailey on the shoulder and asked him.

“We may not get to it since the speaker had a timing conflict and couldn’t make it,” he said.

I felt deflated but somehow didn’t lose hope that at any moment, the presenter would get there. I stayed hopeful during Dr. Maria Lawrence’s beautiful Native American style prayer, which celebrated diversity and asked for it to thrive and prosper.

The reality finally set in that the intra-racism session was a no-go when Dr. Lesley Bogad arrived in time to give the last presentation of the day about “Identities across differences.”

She was joined by two student representatives from the Advanced Learning and Leadership Initiative for Educational Diversity (A.L.L.I.E.D), a one credit class at R.I.C. dedicated to motivating students from underrepresented groups to pursue educational careers.

During the presentation, they talked about how A.L.L.I.E.D. also provides academic and cultural support to students so they can become teachers. As much as I didn’t want to, I had to go home in the middle of the session to prepare for an out of state trip I had the next day.

I shut the door behind me, leaving the small group clustered in front of a large screen with terms and phrases. That day, they taught me it doesn’t take a multitude of people causing a commotion through big demonstrations to make change; change can happen when we decide to expand our own knowledge on a cause and pass it on to the next person.

The conference also showcased the power and validity of on-campus groups like L.I.F.E., which are committed to heightening people’s awareness of diversity while encouraging them to celebrate it. Most of all, attending the conference really put into perspective for me my experience as an ethnic American who has dealt with intra-racism.

One time I was called the "quiet Puerto Rican," a seemingly innocent label that can be a precursor to a million other silent accusations. I’m the snobby one who would rather listen to alternative rock instead of Reggaeton, read a book than cook a meal, and speak English instead of Spanish.

The truth is I grew up listening to salsa, speaking Spanglish (a mixture of English and Spanish), and living off of my mother’s delicious ethnic cooking. So what exactly made me less Puerto Rican than the rest? Is it because I don’t live up to every expectation of what being a Puerto Rican woman is?

On the other hand, not everyone is like this. I’ve recently met people of my race while working for the Spanish press who are not so critical. They notice my accented Spanish but appreciate the fact that I’m trying. They understand the language barrier, reassuring me that I speak Spanish much better than they speak English.

Most importantly, they accept me as one of their own and encourage me to always embrace my Hispanic identity. And I have been doing that, just in my own way. If there was anything the conference also taught me, it was to never allow the indirect criticism from others to make me question my identity as an ethnic American.

No matter what, I am Latina and always will be Latina, and as long as I know that, it doesn’t matter what others think. As an advocate for diversity, I shouldn’t perpetuate the cycle of discrimination by being hateful toward people of my race. I love my culture and there’s no reason for me to be hostile to anyone regardless of what some people have done to me.

Just like everything in life, there are always going to be critics who question who you are; it’s just a matter of turning negative energy into positive motivation to make the world better with the little bit of knowledge that you have.

It won’t happen overnight and it won’t be easy, but I am committed to taking action. And thanks to the L.I.F.E. organization and those who attended the conference, I now know I am definitely not alone.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content