Each year I go through the motions of Christmas, rarely ever feeling fully present. I spend the days leading up to the holiday cooking for my family and baking for my neighbors. I send out Christmas cards. I purchase whatever gifts I can afford. I spend the nights sipping bourbon, wrapping presents, and wondering why the holiday doesn’t fill me with the kind of joy and lightheartedness we see in movies. Then the day arrives and I remember why: my family can be intolerable.

Each year I go through the motions of Christmas, rarely ever feeling fully present. I spend the days leading up to the holiday cooking for my family and baking for my neighbors. I send out Christmas cards. I purchase whatever gifts I can afford. I spend the nights sipping bourbon, wrapping presents, and wondering why the holiday doesn’t fill me with the kind of joy and lightheartedness we see in movies. Then the day arrives and I remember why: my family can be intolerable.

I realize you’re not supposed to say that. To be clear, I don’t mean “intolerable” in a cute, bickering, loud kind of way. I mean that since my mom died, I’m the lone woman in a family populated by troubled white and brown men—white and brown men who seem to only be capable of bonding over one thing: antiblack racism.

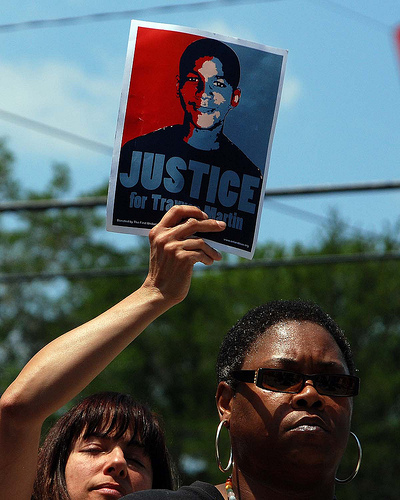

There are two kinds of antiblackness prevalent in my family: the openly hateful and hostile racism that is easily recognizable, and something else that is more challenging to articulate, though painfully common. I have family members who ravenously consume black culture, who worship black athletes like Kobe Bryant, who solely listen to hip hop, but who also say the n-word, who believe “thugs” like Mike Brown got what they had coming to them, and who call President Obama every name in the book, giving a ten-minute spiel about how he hates Mexicans—evidenced, apparently, by his immigration policies. “Typical,” they say. “Blacks hate Mexicans.”

Conveniently, the people in my family can see racism when they believe they are the ones experiencing prejudice. Yes, this means that white family members believe in reverse racism, and that brown family members believe that because we have a black president, antiblackness is somehow a thing of the past and black Americans now have the upper hand. They express these sentiments while throwing around the n-word and dismissing the fact black men and women are being gunned down by police officers as if it’s open season. They don’t see the irony. This level of ignorance is alarming and dangerous, and it has always been this way in my family.

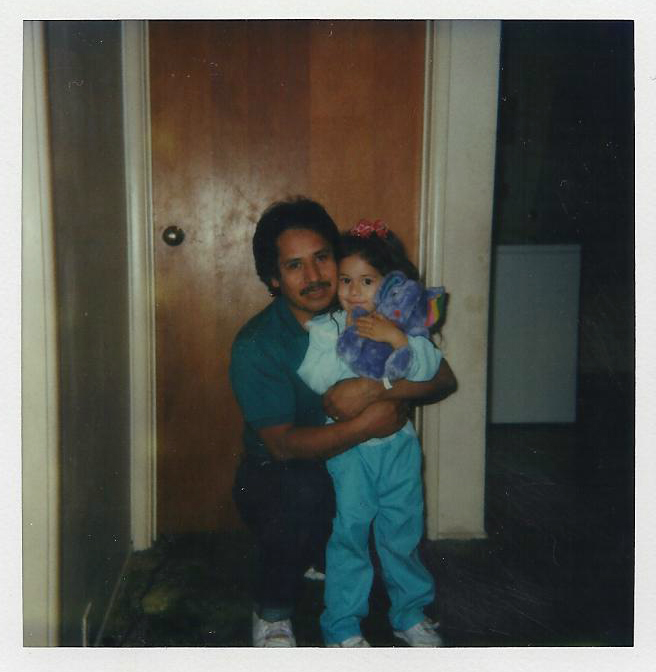

When I was a little girl, my father taught me to proudly proclaim, “Soy Mexicana.” It did not matter that I was biracial, my mother blonde-haired and blue-eyed. It did not matter that I was Americanized and spoke broken Spanish and had few connections to my father’s family, the bulk of whom stayed behind in Mexico when my father made the perilous journey to the States. I was Mexicana and it was something to celebrate and embrace. It was who I was, through and through.

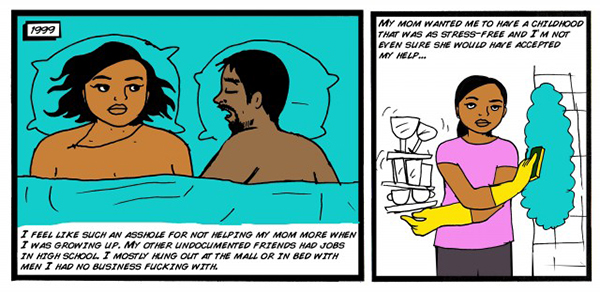

As a child, antiblack racism thrived on both the brown and white sides of my family, but so strong was it on my father’s side that I began to think that hating black people was a prerequisite for being Mexican. I was led to believe that part of being brown was being antiblack.

For whatever reason—and I attribute it to nothing more than semi-decent critical thinking skills and luck (because hatred is very effectively taught)—I didn’t buy into this messaging the way other family members did. Not only did I know it was ridiculous to hate an entire group of people based on the color of their skin, but it didn’t make any sense to me. It seemed that the brown men in my family shared many similarities with the black men they hated and almost always failed to understand that black people were a part of our community, both literally in terms of location and figuratively in the form of Afro Latinos.

In the predominantly Latino city of Los Angeles where I was born and raised, Latino men are gunned down by police officers alongside black men in astonishing numbers. Latinos are also funneled into prisons and sentenced harshly for minor offenses. Low-income Latinos and black Angelenos are primarily impacted by gentrification, making affordable housing for their families and adequate schooling for their children a near pipe dream. My father and my brothers have all been pulled over by cops who had their guns drawn, guilty of nothing but driving while brown. Any sudden movement and there would have been the very real possibility that we’d be spending Christmas with an empty seat at the table and a hole in our hearts.

Still, I can’t convince my family that they should care about black lives. Writers like Aura Bogado have delved into how antiblackness is deeply instilled in Latino families. Black and brown solidarity is often discussed in progressive and radical circles, but personally, I’ve never seen it.

To be clear: this isn’t about the experiences of Latinos. This isn’t an “all lives matter” conversation. It is not my goal to decenter black people. I’ve simply felt the most reasonable approach to getting through to the brown men in my family is to make them understand how closely their struggles are tied to the struggles of the black community. I try, and I fail.

This isn’t specific to my family. Earlier this year, a Pew Research Center survey found that only 18 percent of Latinos surveyed were following the case of Mike Brown. Few Latinos seem to be following the aftermath. The movement born in Ferguson has been so powerful that it has spiraled out into cities across the country, where marches, protests, and die-ins demand that we remember the names of black men and children recently murdered by police, including Eric Garner and, more recently, twelve-year-old Tamir Rice. As I write this, details are emerging about the December 23 murder of eighteen-year-old Antonio Martin, shot and killed by a Berkeley, Missouri, police officer just a few miles outside of Ferguson.

Needless to say, the murders of black cisgender and transgender women rarely get any attention. Black women have been leading the charge in these marches. It has also been black women who have kept the names of murdered black women alive.

The broader message behind this growing movement is that black lives matter. The message is deceptively simple, but for us white and nonblack people of color, asserting that black lives matter comes with the requirement that we continuously center black people. A working knowledge of white supremacy and how it benefits us—and why it must be dismantled—doesn’t hurt either.

It is a tall task that won’t be achieved overnight, but there are small, impactful ways you can push back against antiblack racism every day. Today, on Christmas, I am thinking of the families of recently slain black men and women, those who are facing that empty chair at the table and that hole in their heart. I can think of nothing more disrespectful than allowing the people at my dinner table to speak poorly of those who have lost their lives as a direct result of white supremacy and police brutality—and I won’t allow it.

When I was younger, standing up against antiblack racism in my family was read as being mouthy and disrespectful, resulting in punishment. I am older now and it is easier and safer for me to push back, so I will. In many of our families, every day is filled with antiblack racism, but it seems the holidays amplify it, whether because of alcohol or the “safe” setting family gatherings enable, allowing many to feel free to share the racist commentary they usually keep to themselves.

If you are a white or nonblack person of color who believes that black lives matter, you must behave as if they do when there are no black people present. It is harder than sending out a series of tweets or writing an article the bulk of your family won’t read. (I speak from personal experience.) Pushing back against your family’s antiblack racism is uncomfortable. Pushing back can be contentious. Pushing back can sometimes feel useless, but it is necessary.

I was once told by an artist I interviewed that the most important and transformative work we do is in our own family. I am committed to doing that work. Today, as many of us spend time with our families, I hope we can show up for black people. When our fathers or our mothers or our cousins or siblings assert that Mike Brown was a “thug” or that “police are just doing their job,” I hope we tell them black lives matter, and that they always have, and always will.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content