May in Los Angeles is breathtaking. I know this because it’s all people talk about when the city explodes in Technicolor and flowers rip open. Everything is lush and living, or so they say. I live in Los Angeles too, but I don’t see it the same way. Not anymore. The sunshine is harsh. The colors unkind.

When I walk to the corner liquor store with my sunglasses on and hoodie pulled up, hoping to be left alone, neighbors still yell out, “It’s a beautiful day, isn’t it?” I smile politely, nod. Always polite.

I stood on this same street four years ago, a few days before Mother’s Day. It was early in the morning, around 3 a.m., and I was on the phone with a steely 911 operator, wondering why she was being so cold to me. I realize now it was probably better that way, but in those moments I hated her. I remember saying, “This doesn’t feel real. This feels like a movie. Is this real?” There was silence on the other end of the line.

As the ambulance turned onto my street, I sucked in air like someone drowning. There were no sirens. No flashing lights. I wanted to see the EMTs rushed and sweaty. I wanted adrenaline. But they were calm and slow-moving.

It was my fault. I’d already told the 911 operator I knew my mom was dead.

During the month of May, I will give myself permission to self-destruct. I will drink more than I should. I will sleep more than I should. I will want to do things I’m not wired to do. Sometimes I will. Mostly I won’t.

I will spend an inordinate amount of time thinking about Jumbo’s Clown Room in Hollywood, that dark little strip club that has the power to turn my brain off. I will think about sipping double Crowns and mindlessly throwing crumpled bills onto the stage. I will think about the women and how I want to make eye contact with them in a way I’m usually not capable of. I will think about all the hours of work I need to put in to make a trip to Jumbo’s a reality. It will exhaust me and I will go back to bed.

I broke up more fistfights in my family home than I can count, and I never threw a punch. But this month, there will be days when I wish someone would dare to say something about my dead mom. I will fantasize about how that first punch would feel. And I will think about what my dad said after the EMTs confirmed that my grey-faced mother was dead and probably had been for hours. In front of these men we did not know, he said, “We didn’t even care about her.” It took everything in me not to jump across the bed and murder him.

Mostly, I will search for that hollowed-out feeling I get from Xanax on those days when the anxiety feels like it’s going to burst my heart. That sensation of floating unwittingly through my day, serene and untouchable—not sobbing in a grocery-store bathroom or sitting on the curb in an unfamiliar neighborhood trying like hell to steady my breathing and stop the tears so that I don’t have to deal with a stranger asking, “Are you okay?”

Last May, I lost my mind. Every day, I fought the urge to lie down in the spot where my mother’s body lay for hours before the coroner came. I went on long, meandering walks, listening to the same Perfume Genius album over and over again. (A word of advice: Do not have a soundtrack for your mental collapse. You will never be able to listen to those songs again without being snapped back into that headspace.) I tore apart a pink Bic razor the way I used to in high school. Those flimsy things do an impressive amount of damage. As I watched the blood rise to the surface of my forearm, I thought, “I have no idea why I’m doing this.”

This May, I don’t know what will happen. But I know there will be days when she is all I think about.

Four years ago, I bought my mom a pair of turquoise earrings for Mother’s Day. I had found them at a street fair. My dad and uncle and I had tried to talk my mom into going with us, but at that point she only left the house for doctor’s appointments.

So we left her behind and talked shit about her at the fair. We sat on a green bench on Third Street, the sun beating down on us, the smell of roses everywhere, and talked about forcing her to go on walks, forcing her to quit smoking, forcing her to get it together.

At the fair that day, I took pictures of my dad and uncle beaming, standing in front of glorious restored cars from the 1950s that shined Larkspur Blue and Goddess Gold.

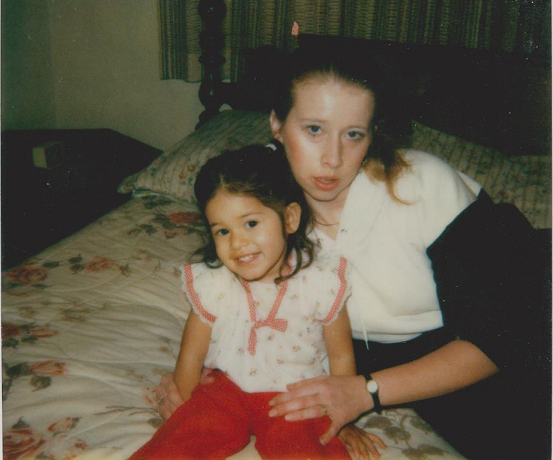

When I look at those photos now, I think about how my mom at that moment had less than twenty-four hours to live. I look at every picture taken before her death the same way. My favorite picture of us smiling with our big, bright eyes? We only had twenty-two years left together. Those pictures from her birthday in 2009, those pictures of her hanging ornaments on the tree, those pictures of her looking dazed in the background as my nieces danced around the living room? She would have less than 365 days left. She didn’t know it. Or maybe she did.

I write this on the anniversary of her death. It’s a beautiful May day. When I walk out my front door, I actually hear birds chirping. The smell of honeysuckle and orange blossoms swirls around. All this afternoon, my dad and uncle have tried to talk me into going to a street fair, the same fair where I bought my mom those Mother’s Day earrings that I would later bury with her.

I was going to give her those earrings. I was going to cook her favorite meal, those bloody steaks she loved so much. I was going to get her pink roses, the kind she bought me on my birthday. I was going to, I was going to, I was going to. But I never got to.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content