Jennifer Cerami garnered a flirty smile from the guard at the Colombian consulate in midtown Manhattan. She was 27, with dark eyes and curtain of long hair. Around her in the waiting room sat a scattering of Colombians with official business back home. It was her first visit, in August of 2005, and Cerami looked uncertain, but not out of place. She cradled a stack of old papers and photographs.

When her number was called, Cerami leaned in to the window, whispering.

“I was adopted in Colombia.”

“Don’t worry,” the consular officer told her, leaning in from the other side. “We all have secrets.”

Like many adoptees, Cerami’s story has several beginnings. One of these is with Linda and Michael Cerami, a young couple from Lindenhurst, Long Island, a blue-collar community of single-family homes and above-ground pools. A high fever had damaged Linda’s fallopian tubes. Michael had lupus, which made domestic adoption difficult. So Linda began to look for a newborn overseas.

Since then, every April, on Jennifer’s birthday, Linda told her daughter this story.

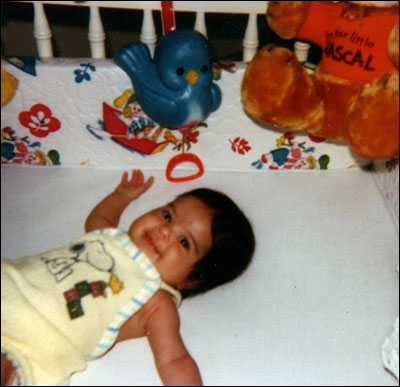

“We wanted a baby very badly,” Linda would say. “And we had to go very far to find you, all the way to a country in South America. I put in the papers, and nine months later, the call came telling us that a beautiful baby girl was waiting for us in Bogotá. You had been left on the doorsteps of the orphanage. Your father and I flew down. No, we never met your mother. But we met the woman who took you in. She led us in to a room with rows and rows of bassinets, and said, ‘Guess who your daughter is?’ Well I walked down the row right past you. But your father stopped there in front of your crib and started crying. And that’s how we were blessed with a wonderful daughter, who is you.”

Jennifer’s adoption was a big event in the closely-knit neighborhood. The Heinzes and the Duffys brought their children to the Cerami front yard for the baby’s arrival, and their daughters — Teresa, Sabrina and Rebekah — became Jennifer’s life-long friends. Summers were games of hide-and-seek and Red Rover, lemonade stands, collecting fireflies. “You wouldn’t have found anything Colombian in our house,” Cerami says. “Nothing.”

Cerami thought of herself as white but there were things every now and then that didn’t jibe. When in second grade other children wrote “basketball” and “butterfly” for words that begin with B, she chose “Bogotá.” While they burnt to red in the sun, Cerami merely darkened. By the time she was ready for prom, Cerami could see the irony of choosing Rodrigo, the only other Latino she knew, for a date.

At Boston College things began to get perplexing for Cerami. She was recruited to the Latino student union, OLAA, though she spoke no Spanish. At a meeting of AHANA, a campus minority group for Asians, Hispanics, Native Americans and African Americans, the leader played “I Believe I Can Fly,” then gave a speech Cerami calls “don’t let the white man bring me down.”

“What was I supposed to do?” Cerami says about storming out of the meeting. “The white man raised me.”

During her second year she moved into the romance language dorm on campus, and studied some Spanish. For a school publication, she wrote an article called “What kind of Latina am I?” “I love my mother dearly,” it reads, “but she raised me as she was raised — Italian.”

Taking the country out of the children

Last year, the U.S. State Department issued immigrant visas to over 20,000 foreign-born orphans, up from roughly 2,000 in 1969. Nearly 200,000 of the 1.6 million adopted minors living in the U.S. are foreign born. Today, exchanging children is a $1.4 billion industry, with travel and adoption agencies, visa wallahs and psychologists to fill every available economic niche.

Inter-country adoption flows in the wake of foreign war and poverty. Developed nations sheltered Koreans after the Korean war. Romanians and Russians followed the fall of Ceausescu and Communism in the early nineties. China’s one-child policy bolstered its top ranking among donor countries in the last decade. But as China’s supply levels off, Ethiopia, Liberia and other African nations are now opening up. In Latin America, and Colombia in particular, the orphan boom came in the wake of civil conflict of the late 1970s and 1980s, which means the largest group of Latino adoptees like Cerami is currently coming of age.

Still, modern international adoption has only been going on for 50 years. It remains an unfinished social experiment, bred from compassion, infertility and post-war economic divides. The legality, propriety and ethics of transnational adoption — its effect on parents, children and societies — is still hotly contested. What began as an idea about “saving kids” has turned into an acute expression of a global society. New laws, such as the Hague Adoption Convention, designed to protect children from trafficking, are allowing transnational adoptees greater access to their pasts. Both cosmopolitan and provincial, adoptees magnify the broader changes in the way we answer the basic question of where we come from.

The biggest development in the history of transnational adoption, though, is the death of the myth of a “clean break” from biological and cultural roots. Today, agencies encourage adoptive parents to foster multiple identities, through organized “culture camps” or sponsored trips home. “Cultural citizenship” spurs South American-themed wallpaper, dress-up clothes, and peculiar show-and-tell moments. As cultural anthropologist Toby Alice Volkman describes in the academic journal Social Text, transnational adoption “forges new, even fluid, kinds of kinship and affiliation on a global stage.” In other words, transnational adoptees, with their socially-constructed identities, are the avant-garde of the present global age.

Jerri Wegner, who has three adopted Colombians of her own, helps educate new families on managing their children’s identity. “I tell parents,” she says, “that we have to take our children out of Colombia in order to bring them home, but we never have to take Colombia out of our children.” Her agency, Friends of FANA, organizes Spanish-language camps in Colombia, and country-themed gatherings in upstate New York, where kids are fed Colombian food and encouraged to play soccer wearing Colombia’s yellow national team jersey.

Hollee McGinnis, a sociologist at the Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute who studies identity in adoptees, wonders whether this is the best approach. She argues that “culture camp” may unnecessarily complicate the development of a healthy identity. Her research describes two layers of culture that every adoptee has. The first is an “external” layer of food, attire, language and history — things anyone with a little curiosity can pick up. But the second layer of culture is more elusive: “the culture of being,” which can only be acquired by living it. “It’s how you walk, interpret the world, your internal values,” McGinnis says. “Most adoptees lose that.”

A shifting sense of home

The Colombian in Cerami’s face is visible, but she moves like a girl from Long Island, with a wide, forward-pressing gait. These days, Cerami works as an analyst at Ann Taylor’s online marketing division, in Midtown. Before that, she did a stint on the floor for Sephora. She squeezes appointments in before racing off to the New York Sports Club, then heads home to a Lower East Side one-bedroom where her open laptop chirps with instant messages. She talks to her mother every day. “I had fights with my mother just like any teenager,” she says, “but now she’s my best friend.” And still, Cerami holds on to a desire “to be from some place.”

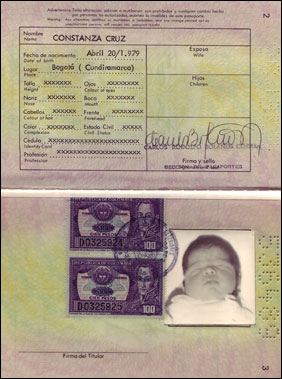

Like for many adoptees, Cerami’s search began with documents. Her first came in a DHL envelope, just a week after her visit to the consulate: a birth certificate. “Not a mystery solved,” she says, “but more like answers to questions I didn’t realize I had.” Her own name is Constanza Cruz. She had not been left on a doorstep.

That winter, Cerami got in touch with her orphanage in Colombia. A friend’s wedding in South America had given her an excuse to stop off in Bogotá, the first time any Cerami had returned to Colombia since Jennifer was three months old. Through a contact at the consulate, Cerami sent out an announcement on Colombian radio asking Constanza Cruz’s mother to call, but nobody responded. Colleagues at Cerami’s office, who had been following her revelations, offered donations for the orphanage, which Cerami planned to visit. Come Christmas, Linda drove her adopted daughter to the airport.

“I’m afraid I’m not going to feel,” Cerami told her mother in the car. “I’m afraid I’m going to go down to this country and be completely not affected by what I see. My life is not going to change. This isn’t going to have a connection with me, and what does that mean then?”

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content