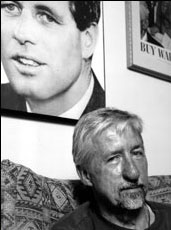

Tom Hayden is living proof that one person can make a tremendous difference in the course of a lifetime. Perhaps best known as a member of the Chicago Seven, Hayden helped organize street demonstrations against the Vietnam War at the 1968 Chicago Democratic Convention. Hayden began his life in activism as a founding member of the widely influential group Students for a Democratic Society. Active on a host of issues in the early 1960s, he was arrested and beaten in rural Georgia and Mississippi as a Freedom Rider. He later became a community organizer in Newark where he helped create a national poor people’s campaign for jobs and empowerment. When the Vietnam War invaded American lives, Hayden became an increasingly vocal opponent through teach-ins, demonstrations, and writing. Due to his involvement in the 1968 protests, Hayden was indicted with seven others on charges of conspiracy and incitement. After five years of trials, appeals, and retrials, he was acquitted.

Hayden spent the 1970s organizing the grassroots Campaign for Economic Democracy in California. He was elected to the California state assembly in 1982, followed by the state senate ten years later. He served in public office for eighteen years until his retirement in 2000.After 40 years of activism, politics, and writing, Tom Hayden remains a leading voice for ending the war in Iraq, eradicating sweatshops, saving the environment, and reforming politics through greater citizen participation. Recently, InTheFray Travel Editor Michelle Caswell spoke with Tom Hayden via email and learned how those committed to reshaping America might put their ideas into action.

The interviewer: Michelle Caswell

The interviewee: Tom Hayden / Los Angeles

You have recently been working on behalf of No More Sweatshops!, a California-based workers’ rights organization that has been pressuring public agencies to end the practice of buying sweatshop-made products. Has the ‘no tax dollars for law-breakers’ campaign had any recent successes you would like to talk about?

After an interminable struggle and wait, the cities of Los Angeles and San Francisco signed monitoring contracts with the independent and pro-worker Workers Rights Consortium (WRC), [in December 2006]. They should be able to do four site visits this year as well as obtain complete disclosure of factory sites and subcontractors.

How are all of the issues you advocate for — an end to sweatshop labor, conserving the environment, ending the war in Iraq — related?

I would say they are connected through Machiavellian power structures as well as … in the new populism we see. While organizations have their reasons to keep the issues separate, no one can deny that Iraq is about oil and that anyone concerned with global warming, for example, should be equally passionate about global suffering.

You devoted the early part of your career to fighting for civil rights as a Freedom Rider in the South. Four decades later, schools are segregated across the country and the economic gulf between blacks and whites is still astounding. In your opinion, was the civil rights movement a success? What went wrong?

Yes, the civil rights movement prevailed against the Machiavellians in achieving voting rights, civil rights, and the end of the Dixiecrat political coalition at the time. To a lesser extent, the movement’s energies were directed towards jobs, for example, in the demands of the March on Washington in 1963 and the War on Poverty of 1964. We ran into two walls. First, the war in Vietnam sapped any resources to confront the battles at home. Second, the end of segregation removed the incentive for the plantation economy, and there was no public sector jobs strategy to fill the void of employment. Had the assassinations not happened, the political energy might have been renewed successfully.

While there have been some major protests against the war in Iraq and public opposition to the war is growing, we haven’t seen nearly as big of an outcry as in the 1960s protests against Vietnam. Why is this, in your opinion?

Actually the 2002 and 2003 protests were larger and earlier, and the American public came to regard Iraq as a “mistake” faster than during Vietnam. But the comparative images do make the Sixties appear grander, if I can use such a word. As [for] reasons, in the Sixties it was necessary to be in the streets because there was no inclusion. As a result of the Sixties, much of the consciousness came “indoors,” to the classrooms and neighborhoods, so to speak. But also the end of the draft has been a big factor in subduing potential restlessness on the campuses.

Do you think young people are apathetic today? What can we do to instill a culture of activism among young people?

It’s up to each generation. We had no elders in the 1960s; the question for people like me is how to be an elder, not a leader, today.

Can you speak about your work advocating for U.S. Congressional hearings on exiting Iraq?

After the 2004 elections, I was terribly afraid that the Democrats who were anti-war were shell-shocked by defeat and in danger of retreating further away from an anti-war position. I became involved that year in helping stir some interest in the progressive Democrats taking an open interest in what is now the subject of the moment — not how stupid it was to invade Iraq, but how … the movement and its political allies [can] design or demand a blueprint for withdrawal. Since 2005, most of the Democrats and some Republicans have come around to the need for an exit plan including a withdrawal deadline. They won’t go much further unless really pushed during the upcoming presidential elections by activists on the ground.

Many young idealists from the 1960s gave up their activism as they got older. Why have you stuck with it? What motivates you?

My own story is connected to the story of these times, and I seem drawn to following the stories to their end. I also remain easily angered by bullies and killers, and don’t understand why anyone would get tired of holding them accountable.

What do you think is the future of the Democratic Party? Do you think it is possible to advocate for change within a two-party system? How can the left take back the Democratic Party? How have you managed to make the shift from protesting the Democratic Convention to being a delegate without compromising your ideals?

I believe in the creative power of independent social movements, but also that when those movements grow large enough they will [and should] flow into electoral politics like a tributary of a great river. I don’t think the Democrats can be “taken over” because at their core they are embedded in the Machiavellian elite. But the rank and file of the Democratic Party can and will propel very progressive candidates to certain offices where the movements are strong, and they can even challenge in the presidential primaries during crises like this one.

How can people get involved? What is something that someone can do right now to make a difference in his or her community?

I hope that people can connect their work on a personal level with larger strategies for change. An example, but only one, would be to get in the face of military recruiters at your local campuses. Not only will you save some kid’s life, but you will contribute to shutting off the military manpower (“cannon fodder,” we used to say) necessary to keep the Iraq War going. The war will end when enough people-power pressures the pillars of the policy, if you see what I mean.

Michelle L Caswell

Dear Reader,

In The Fray is a nonprofit staffed by volunteers. If you liked this piece, could you

please donate $10? If you want to help, you can also:

For Hanukkah this year I may have received the most meaningful gift I’ve ever been given. My family isn’t all that big on the gift-giving associated with that time of year. Like many people, it’s more about the time we spend together as a family than the price tags or the presents. We get simple things, like Dutch chocolate letters, an old tradition from my dad; or useful things, like teacups or socks or warm sweaters. And to be honest, this year I didn’t even want a gift. Everyone was happy and healthy, and that’s all that mattered.

For Hanukkah this year I may have received the most meaningful gift I’ve ever been given. My family isn’t all that big on the gift-giving associated with that time of year. Like many people, it’s more about the time we spend together as a family than the price tags or the presents. We get simple things, like Dutch chocolate letters, an old tradition from my dad; or useful things, like teacups or socks or warm sweaters. And to be honest, this year I didn’t even want a gift. Everyone was happy and healthy, and that’s all that mattered.

A conversation with Tom Hayden on being stirred by bullies and killers.

A conversation with Tom Hayden on being stirred by bullies and killers.

Explorations of history and heroism in London.

Explorations of history and heroism in London.