- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

New York City's Department of Sanitation slogged through a year's worth of city garbage to see exactly what people throw away. Both the recycling and the waste were analyzed and compiled into a very interesting and telling report entitled: "The New York City 2004-05 Residential and Street Basket Waste Characterization Study." The trash study was the only way the department could decipher people's habits and in turn create better recycling programs. The recycling habits of New Yorkers have improved from 15 years ago, during the last trash study, but there is definitely a need for even greater change.

Residential trash contains ¼ recyclables

So what exactly is in the garbage? In residential trash, organic material makes up the largest segment at 47%, with recyclable paper at 15% and plastics at almost 12%. But of this refuse, 23% is easily recyclable material that just wasn't separated into the recycle bin. This includes paper, metal, glass, and plastic that people couldn't be bothered to toss into the blue container rather than the black one. And this is just residential waste.

Street litter baskets contain ½ recyclables

Street litter baskets are the worst offenders of holding potential recyclable material that is needlessly tossed away. Almost half — that's 47.14% to be exact — of street basket waste can be recycled but isn't. Newspapers make up the bulk of the garbage at more than 15%, with other recyclable paper at 15%, glass at 7%, metal at 6%, and plastics at almost 3%.

What the study doesn't show is the amount of people who make their livelihoods by picking through the street baskets for recyclables. Cans and bottles make up the bulk of their haul because the bottle deposits can be cashed in. Old newspapers and cardboard aren't attractive because there is no payback for digging those out of the trash. If the baskets weren't picked through, the amount of recyclables would be even higher than 47%.

Overall results

Overall, 35% of the refuse studied is recycled. But recycling habits of New York's citizens should be better than only 77% residential and 53% out on the street. On the Department of Sanitation's NYCWasteLe$$ website, there are numerous tips on how to reduce waste as well as information about recycling.

Recycling is mandated by law, so you are actually breaking the law when you don't recycle. At home recycling couldn't be easier. You either are given curbside recycling bins that are picked up on certain days, or your apartment building has different containers for your different recyclables. Throwing away trash and tossing recycling into its required bins takes the same amount of effort. When you are outside of home, think about what you throw away before you do it. How difficult is it to hold on to your read newspaper until you get to the office or home so you can recycle it? Can you put your used drink can or bottle into a bag and keep it with you until you find a place to recycle it?

Little acts like this will help keep one less thing out of a landfill. You might think that you aren't contributing much, but if the other eight million people in the city also decided to not throw away their newspaper — that's 8,000,000 less papers in the trash.

keeping the earth ever green

Right now I am teaching a seven-day creative writing program at a public elementary school in Buffalo, New York. On the second day I had the students write collaborative stories: One child wrote a fictional story's beginning, another wrote the middle, and a third penned the conclusion. Most of them struggled with this. Exchanging papers was an ordeal, and many were not happy with the stories they were expected to add onto. Girls did not want to write the plot for a story about football; others thought the people with whom they were supposed to trade papers were icky. But some rose to the occasion and collaborated to produce solid stories.

One in particular caught my eye. It was about someone serving in Iraq. Here's what the students wrote:

Once there was a man named John. He was going to Iraq. He was going to fight for our lives. But then he got a little scared because he was thinking of what might happen to him. But then he was feeling sad because he missed his family. Then he went to Iraq, and when he got there, he felt really better. So he got a popsicle, then he said, “I am going to write a letter to my parents.” He got another popsicle, then he went back to war. This time he was not scared, so he got all the stuff he needed. He got the best gun he could. He wanted to see his parents.

Say what you will about the popsicles and the fact that John ceases to be scared when he gets to Iraq, there is some real awareness here about the dangers of war.

The majority of the attention at Sunday’s Superbowl parties certainly wasn’t always on Peyton Manning and the Indianapolis Colts.

Friends and I attended a Superbowl party at a local restaurant, and it didn’t take long before one of the truer highlights of the game – the commercials – took center stage.

A well-dressed business man walks down a hallway, talking mostly indecipherably from background chatter in the restaurant about his company. No one pays much attention and the commercial is dismissed as another ‘talker,’ clearly not expecting bouts of laughter. But when the male lead takes off his glasses and steps into the marketing room for GoDaddy.com, everything changes.

The question then became, “So what does GoDaddy.com do anyway?”

The ad, linked here, highlights well-endowed women in white logoed tanktops jumping up and down gleefully, while being rated by a number of “biker types,” clad in oversized black t-shirts. If that wasn’t enough to have the eyes of countless men in the room fixated on big screens – the waterworks would do exactly that.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but somehow, wet t-shirt contest doesn’t scream domain registry and web hosting to me. It screams sexism and objectification.

Sure, the Superbowl’s target audience is men, ranging in ages from their late teens on up to the 50-something population. But perhaps the visual was unnecessarily crass and sexualized. Scratch perhaps – that’s a definite.

The clencher: in a user poll by AOL Sports, the commercial didn’t fare that well against other, less “in-your-face” advertisements. In a poll for 2nd-quarter commercials, GoDaddy.com was trumped by the Budweiser dalmation, which came in with 31 percent of the vote. GoDaddy.com’s busty women only held the attention of 2 percent of those polled.

However, don’t let me mislead you. The stereotypes still sell.

Moving on to the Snickers kiss commercial, which painted two unmistakably ‘manly’ men meeting for an accidental kiss after sharing a Snickers bar.

Several problems emerge – the clear media construction of masculinity (who really rips hair off of their chest? Male friends at our table were polled, and apparently that takes a clear level of insanity), as well as the sounds of disgust echoing from around the room when the men’s lips met.

Even in post-Brokeback America, the general population can’t wrap its head around the idea of two men liplocking, whether on the big or small screens – or in real life.

Why is being gay, or being uncomfortable with homosexuality, so accepted in the United States? Why is homosexuality considered a threat to masculinity, as shown in the candy bar ad’s portrayal? What are advertisers selling today, their world views or their product?

Given the choice between the rest of the ads and the cute, yet safe, dalmation by St. Louis-based Anheuser-Busch, I’ll take the dog.

With Valentine’s Day looming, February greets us with commercials reminding us to buy timeless gifts — diamonds, anyone? — for our sweeties. But some of the most timeless presents cannot fit into a jewelry box or be gift-wrapped. And though some may have been mined as recently as the diamonds Zales wants to sell you, many come from another era and don’t sport a price tag.

In this issue of InTheFray we explore relics of the past and their value to the present. We begin in Brooklyn and Philadelphia, where Sasha Vasilyuk treats us to some Russian intellectual football, better known as “KVN,” a game show of comedy and music sketches in which Russian immigrants participate to hold onto a fragment of their past. In Detroit, Scott Hocking and Clinton Snider look at the city’s cyclical nature, from wasteland to thriving metropolitan area, to deserted area, to booming urban centre. In RELICS, their art installation, the two ask how long it takes the old to be forgotten. Meanwhile, across the pond, Jacquelin Cangro discovers Giants among us on a visit to Postman’s Park, where everyday people’s achievements are commemorated.

We then offer three different relics of love: ITF Literary Editor Annette Hyder and ITF Contributing Editor Kenji Mizumori’s Mixed Media Valentines to loves come and gone; a quilt that Rachel Van Thyn’s mother put together One piece at a time, using squares spanning three generations; and Jen Karetnick’s musings On vintage handkerchiefs passed down by her grandmother.

Rounding out this month’s stories is ITF Travel Editor Michelle Caswell’s interview with Easily angered activist Tom Hayden, who shares a veteran critic’s insight on the Iraq War, desegregation, political apathy, and making a difference.

Enjoy!

Laura Nathan

Editor

Buffalo, New York

Toward the end of her life, my grandmother went shopping for birthday and holiday gifts in her own apartment. Some years I received pantyhose; others, a milk glass vase or a brass alligator nutcracker.

Although I never used the last present I received from her, I kept them: three pristine, precisely creased, embroidered muslin handkerchiefs. They have survived college in one state, graduate school in another, and the arrival of my own family in a third. Aside from the figurative ties they give me to my grandmother, whose nose I have inherited, I have always considered them valuable.

But value has a different meaning when it comes to eBay.

One day I was browsing its “clothing, shoes and accessories: vintage” category when I found a listing for an inordinate amount of women’s handkerchiefs. In fact, 238 lots were for sale that very week. The cheapest, a set of four holly-embroidered Christmas hankies, was going for 99 cents. The most expensive, an assortment of 154 floral “everyday ladies” hankies, was on sale for under $60. At 38 cents a pop each, these weren’t exactly Caspian caviar.

On a visceral level, I was a bit disappointed in these anonymous sellers. I know that many dealers bought these products from estate sales and have no attachment to them other than the scant money they paid. But other sellers are daughters and granddaughters who may have cleaned out closets after the owner’s final stroke or battle with cancer. Isn’t the hawking of these long-held possessions akin to the selling of memories?

And at rock-bottom prices, no less.

Sentiment aside, I have no practical use for these tiny patches of gauze, trimmed with faded cross-stitch and permanently scarred with folds. What does one do with such items? Turn them into appliqué lampshades? They’re more suitable for polishing the furniture than they are for clearing the sinuses.

But thanks to my robust love for fiction and a vivid imagination — something else I inherited from Grandma — I can visualize one of these lace-and-linen confections tucked up her three-quarter sleeve.

Each brings back a piece of her. The off-white one with the scalloped edges reminds me that Grandma Min pickled the neighborhood’s best herring in sour cream sauce, heavy on the onions the way my dad and I like it. The eggshell one, with the crocheted border, takes me back to her fragmented square of a linoleum kitchen table, where I sat in my nightgown, watching as she cooked breakfast. She always salted the eggs before scrambling them rather than after, making them taste so much better. The handkerchief that was imported from Europe — and still in its original packaging — takes me to my grandmother's girlhood during World War I. She escaped in a covered wagon driven by her mother across the continent to a ship that would take them to America.

Although in the final decade of her life, Grandma Min blew into disposable tissues like the rest of us, and these vintage handkerchiefs are no longer intended for use, their personal history will always be nose-worthy.

Chances are, my own grandkids are going to receive them, and while they may be initially puzzled, perhaps in the end, they will discern the handkerchiefs’ true value.

It is 6:30 p.m. and the brash young comedy team the Illegals have only half an hour left before the women in the Russian hair salon kick them out. Half an hour is not a lot of time, they figure, but it’s enough to run through their comedy routine one more time.

As the sound of an upbeat melody starts rolling, Semyon, Ruslan, Alexei, and Paul take two steps toward the mirror wall of the room, raise their arms, and smile smugly. Then they break into a flurry of short skits and absurdist one-liners, all in Russian.

“Do you have anything for the head?” Ruslan asks, looking pained, in one scene.

“Here, take an ear …” answers Alexei.

Looking in the mirror after every joke, the Illegals pretend to see the blinding stage lights and the cheering audience that will greet them in two weeks at the popular Russian comedy competition called KVN.

KVN, roughly translated as the “Club of Humor and Wit,” is a team game show, where students from different colleges, cities, and countries compete by presenting comedy sketches, humorous musical numbers, and improvisation. It is fast-paced and intense; one of the show’s creators once described it as “intellectual football.” With no direct equivalent in other cultures, KVN is an essential component of modern Russian life and a popular import of Russian-speaking immigrants around the world.

The fifty-year-old tradition started after the death of Stalin. As Soviet control began to ease in the late 1950s and 1960s and television sets became more common in Soviet households, a group of Russian university students created a unique television game show. At first, KVN was a question-and-answer game based on a Czechoslovakian show and similar to Western models. Although the teams had to give correct answers, witty answers were also allowed. Soon, the producers began to emphasize humor, making up amusing contests and assigning the teams funny skits to prepare.

With lightheartedness rarely seen at the time and humor normally reserved for the underground subculture, the nationally televised show immediately captured the Soviet imagination. During each game, life on the streets would cease, and the next day, everyone would discuss the jokes they’d heard. KVN aired through 1971, expanding to more and more teams from different cities and Soviet republics, but then was cancelled due to criticism from government officials. It was revived only at the dawn of glasnost, when emerging liberties and disarray in the government allowed for less control of what was being said on television.

A humorous critique of the world in the form of popular entertainment, KVN has continued almost unchanged since Soviet times. In Russia and other ex-Soviet republics, being a “KVNshik” can make one a celebrity on par with famous professional comedians. Away from its television audience, however, KVN is — for some 40,000 Russian-speaking immigrants in the US, Israel, Germany, and even Australia — not a road to fame, but a unique national tradition worth holding onto in a foreign land.

Looking in the mirror, the Illegals rehearse a scene from one of the three essential contests forming any KVN game, including the upcoming quarterfinals. Each game starts with the “Greeting,” where a team introduces itself with short tidbits of humor, loosely connected miniscenes, and dialogues. Then they move on to the “Warm-Up,” an improvisational contest in which each team has thirty seconds to come up with a funny answer to a question. Then comes the “Homework,” usually the longest and most theatrical part of the KVN game. It is akin to a sketch from Saturday Night Live and is rehearsed in advance. The Homework skit needs a lot of preparation, and each teammate has to be on top of his game.

For the Illegals, one of the key moments in the Homework is a scene borrowed from “Beauty and the Beast.” Ruslan — a blond, blue-eyed, big-boned Byelorussian — plays the merchant, whose three daughters (Paul, Alexei, and Semyon) ask him to bring back gifts.

“What would you like, my oldest daughter?” Ruslan asks.

“Bring me a decorated shawl,” replies the redheaded Paul, “from Gucci!”

“What would you like, my middle daughter?”

“Bring me an older sister who is not stupid,” says Alexei, the tallest of the three “daughters.”

“What would you like, my youngest daughter?”

“Bring me alimony for three years from that Beast!” answers Semyon, carefully enunciating every word.

At the end of the scene, everyone starts talking at once. Paul gets criticism for his bad pronunciation of “Gucci.” He repeats it several times, giving more punch to the “cci.” Semyon blushes deeply as he tries to argue with Ruslan about the wording of the skit. Meanwhile, twenty-five-year-old Alexei — the team’s oldest member — smiles to himself like a satiated cat. His hair is sticking out and worn-out jeans hang on his tall, thin body. Over the clamor, he hears Sasha, the team’s music assistant and only man behind the scenes, scolding Ruslan.

“You show off too much,” Sasha says. “And you eat up lots of words.”

“He is fine, leave him alone!” says Alexei protectively. Putting his hand on Ruslan’s shoulder, he tells him, “You are a star.”

Other, less poignant criticism continues to echo through the room as everyone gets ready to leave. Ruslan, who has the springy walk of a boxer and a childish smile, tells the skinny, stylishly dressed Paul that he does not like him as an actor. “Do you like me as a man?” Paul says flirtatiously as everyone chuckles.

“Bunch of homos on this team!” says the dour KVNshik as he walks out into the cold Brooklyn night.

The Illegals, whose four members currently live in three states — New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania – are a truly heterogeneous team. Unlike the majority of Russians who immigrated as Jewish refugees, Ruslan and Alexei both moved to the US three years ago, using a four-month visitor exchange program to stay on the new continent. Before the two friends met, Alexei and a few other young illegal immigrants created a KVN team based in New Jersey and named it, appropriately, the Illegals. At first, many KVNshiks, who have lived in the US since the biggest wave of Russian immigration in the early 1990s, thought the laid-back style of the Illegals was strange. Others, however, saw in their style a way to improve KVN’s American league.

“I first met them at the KVN festival in 2003,” remembers Sergei, a member of a Chicago team and a friend of the Illegals. “They brought freshness and youthful inspiration into the game. I immediately wanted to meet them. Their acting ability and quality of humor put them on a level higher than the other teams in the league.”

Yet so far, the Illegals have not been very successful. They left their first game due to disagreements about the judging. Then, they regrouped to incorporate some members of a team from Philadelphia — Semyon and Paul among them.

Semyon, who has attentive eyes and an apologetic manner of speaking, did not participate in KVN back in Russia, but loved to watch the games on TV. Unlike Alexei and Ruslan, he is not an illegal immigrant. After he moved to Philadelphia with his parents five years ago, he found out about the local league and created his own KVN team. “I wanted artistic realization,” he explains. “Some people paint, others play a musical instrument, and I play KVN. It’s a great feeling when you’ve written something, performed it, and the audience liked it. I feel artistic satisfaction.”

Semyon invited his childhood friend and neighbor, the redheaded Paul, to join the team. Paul, who had just moved from Israel, did not remember much Russian. But he was stylish and funny and had a good attitude. “I basically came to KVN for sex,” Paul says impishly. “But now I am the one who has to supply all the chicks.” Outside of KVN, Semyon and Paul work and go to college. They are majoring in film and hope to make a documentary about the plight of young illegal students like their teammates.

The last member to join the Illegals was Ruslan. Although he contributed professional KVN experience from Russia, the team still lost last season’s semifinals. “I went to rehearsals like a fool with a notebook and a pen,” says Ruslan. “And everything just ended in drinking.” Although Alexei’s official response to Ruslan’s complaint is “Nothing brings people together like vodka,” he blames their loss on razdolbaistvo — a slang word that means irresponsibility, carelessness, and even laziness.

“Razdolbaistvo is both our flaw and our style,” he says. “We can’t get together, we can’t rehearse, we can’t figure out the music. That’s why we lost at the semifinals last year. We were funny, but unorganized.”

Less than two weeks before the game, Ruslan is having breakfast with Alexei at a Russian restaurant in Brooklyn. A rowdy group of men drink vodka and argue about yesterday’s hockey game. It is noon. As they wait for a steak, chicken livers, and apple blintzes, Ruslan explains that he has been playing KVN since he was thirteen.

“I even remember the first joke I had to say,” he says, his blue eyes gleaming. “We had this scene: an ad for Aeroflot. The guy looked out the window and said ‘Oh, look, flying elephants.’ And I took his glass away and said ‘Okay, that’s enough for you.’”

“You ripped!” says Alexei mockingly as he digs into his steak.

“When I first started, I didn’t write my own jokes and didn’t really act onstage,” continues Ruslan. “I learned how to write jokes, how to feel the text. So, KVN is not about talent, but experience.”

“I had talent, but I’ve killed it working with these guys,” says Alexei with a sigh. “People told me to go into acting.”

“Well, people told me that, too,” says Ruslan defensively.

“No, no, they lied. Besides, I was the one who told you that. Anyway, I didn’t want to go to acting school, because I like it as a hobby, not as a profession. I’ve always played the role of a fool, and an actor is more than just one character of a fool. My first role ever was to play a fool, and then the second, and the third, and it stuck. But I sort of act like a fool in life, too. Maybe that’s why this role is easier for me.”

Alexei, who became a KVNshik when he entered university in Russia, thinks he should quit competing after this season. “This game is for the young,” says the twenty-five-year-old. “I need to quit soon. I am way too old and KVN takes away so much time.”

“It takes away health, too, since we need to drink a lot,” interrupts Ruslan.

“Time and nerves,” finishes Alexei, who goes to college and keeps a night job at a Russian TV station.

“A great classic once said that KVN is not a game, it’s a lifestyle. Of course, no one knows what that means, but it sounds beautiful,” says Ruslan. He turns more serious and adds, “Someone who once participated in the games, I mean like fully — writing, acting, and stuff — cannot just quit.”

But Alexei doesn’t want to dwell on the serious. “Anyway, to come back to talking about talent,” he says. “Me and him play pretty much all the roles. Wait, what the hell do those two do?”

“Well, one is a redhead, so if something goes wrong, we can always blame him.”

“He also makes great tea.”

“Yeah. And the other one, Semyon, he is just a nice Jewish boy who doesn’t do much.”

“Every team needs to have one, you know,” concludes Alexei.

In Russia and many former Soviet nations, every KVNshik nurtures the hope of becoming a celebrity. But in the US, where an independent KVN league started ten years ago, stardom is out of the question. Although in format and style the American KVN league mirrors the High league of Russia, it does not have millions of fans. The teams sponsor themselves, auditoriums rarely fill up to capacity, and only a few KVN games make it onto a local Russian TV channel.

However, the enthusiasm of local KVNshiks like the Illegals makes them stand out among the mass of Russian immigrants. They do not resemble the majority of older Russian Americans, who, having left the old country for good, severed all ties with modern Russia. They are also not like many younger Russians, who grew up in the US and know little about their country of origin.

Instead, the comedians grew up in the post-Soviet Russia of endless possibilities. They emigrated not because they had to, but because they could. They are media-savvy children of globalization — in their spare time, they browse Russian websites and watch Russian satellite TV. Unlike some immigrants who are completely detached from the life of a cold country thousands of miles away, young KVNshiks often exist in a strange niche between here and there. On the one hand, they have Russian friends, Russian wives, Russian vodka. On the other, they are integrated in American society — they graduate from schools like Harvard, Berkeley, and NYU and work as programmers, businessmen, or lawyers.

But living in this niche, American KVNshiks find themselves at a disadvantage. Surrounded by a different culture, they have neither the structural and financial support enjoyed by Russia’s nationally televised KVN, nor the possibility to achieve true stardom as Russian-speaking comedians. Even their humor reflects their unique situation. To entertain their small, immigrant audiences, they often turn to localized jokes about the immigrant experience, be it Brooklyn restaurants or linguistic mix-ups.

When he first saw American KVN, Alexei thought it was very amateur. “Three years ago it was just horrible,” he says. “The favorite theme was when a dude dressed up like a woman, came out onstage, and said something. The first time I saw that, I realized that you can’t perform here. But everything has been changing and looking more like the real thing. If there are no young teams who want to compete, there can be no KVN. What would be left are the older teams. They are nice guys and their humor may be fine for this audience, but they are not helping KVN evolve. We need more young teams, especially guys from back home.”

With their experience from “back home,” the Illegals are trying to raise the level of the American league by bringing humor that is both poignant and not immigrant-specific. Their other choice would be to give up KVN completely. But even with this amateur league and a limited audience, playing KVN is worth their time. It is a tradition, a form of identity, and a way to preserve their culture.

“We can spend a whole evening talking about KVN and not even notice it,” says Alexei. “It has become part of our lifestyle.”

At 11 p.m. on a Thursday, Alexei is working the controls at the Russian TV station. With little time left before the game, he is surprisingly calm.

“We still have a lot to work on, and we only have one day left — that’s definitely a big minus,” he says. “At the same time, we are funny dudes, we look cool onstage, and we are pretty good actors. I don’t remember a game when we totally rehearsed. If one joke doesn’t get through to the audience and then the second, people see that the team did not rehearse. But if the first joke gets to them and the second, then the audience is in the right mood, they clap and cheer and don’t pay attention to the little mishaps, because everything is absorbed by the overall atmosphere.”

His deep voice leaves the hope for that magic atmosphere lingering in the empty control room. “Even though we are jerk-offs, everyone still wants to win. We all have problems, work, school, some of us have both work and school, not enough time, but you gotta have more in life than work or school.”

Alexei wants to win this season because he is not sure the Illegals will play next year. It’s not only his age. He is also worried that Ruslan may go back to Belarus. Although he has just received his work permit, Ruslan is waiting for a travel visa to see his friends and parents back home. For now, he refuses to buy a car, because he doesn’t want “to get anything that would tie me to the US.” If he does not get the visa before the end of the year, he will leave the country for good. At least in Belarus, Ruslan — the kind of person who sees the world “as if it’s made up of punch lines” — has a bigger chance of becoming a real KVN star.

Two nights later, there is commotion outside the dressing rooms of the Jewish Community Center in Philadelphia. Leather-clad Russian men smelling of liquor swagger down the hall, with Russian women in short skirts and heavy makeup trotting behind them. The women smile confidently, leaving a trail of sweet perfume.

Two women come back to the green room of the Illegals, with cigarettes and cans of Red Bull for the teammates. Semyon and Alexei open the cans and drink. All four Illegals put on hip, dark-gray jackets, beige slacks, and bright-colored shirts. The female admirers straighten out the men’s jackets and put gel in their hair. With only a half hour left before the game, the room is tense. There are endless bottles of cognac and juice on a table surrounded by drinking visitors. Semyon is angry and nervous because Ruslan has been drinking heavily.

“I’m gonna kill that fucker!” he yells. “How can he do this? The game is about to start! Where the fuck did he go?!”

Someone walks into the dressing room and asks, “Why do you guys look so gloomy?”

“Why should we be happy if we’re losing?” says Alexei, half to himself. He circles the room, muttering his lines and squinting nearsightedly. Sergei from the Chicago team tries to rally him. “Capture the audience, this scene is totally on you. If you capture the audience, you’ll rule, I promise you!”

Alexei nods absentmindedly, but does not speak. Ruslan comes back. He does not seem very drunk. “I’m always nervous before the game,” he confesses. “But when the fanfares sound, it goes away.”

Five minutes before the start of the game, the Illegals gather in a tight circle, put their hands together in the center, and yell in chorus, “We swear to you, O goalkeeper, that we will never lose!” They jump up, screaming and making punching gestures.

“I’ll destroy everyone!” bellows Alexei.

The female fans line up to kiss the teammates and wish them luck. An entire minute is filled with a seemingly endless “mma, good luck, thanks, mma, good luck, thanks …”

“It’s like we’re leaving for war,” Semyon says.

The auditorium is almost full. There are no empty seats, someone jokes, just unsold tickets. E. Kaminskiy, an experienced KVNshik from a legendary Russian team of the late 1980s, hosts the game. The jury, consisting of older KVNshiks, two of last year’s champions, and a TV newscaster (the only woman), sit in the first row. Five teams are competing tonight: NYU (famous for winning ten years ago), ASA College (famous for ever-changing members), the Philadelphia team (famous for attractive members), Nantucket (famous for constant intoxication), and the Illegals (famous for razdolbaistvo).

The game starts with the Greeting. “The Greeting is a chance to conquer the audience,” Sergei notes. “It’s all psychological. You need to click with the audience from the first phrase, with your energy and charm. If the audience reacts to you, then you’re the king.”

In order to pack in many disconnected jokes into the fast-paced Greeting, KVNshiks often imitate the format of TV ads, with their spicy one-liners. When the Illegals take the stage, Alexei announces, “American masochists ask to increase the punishment … for masochism in America!” The young audience is quiet. They process the joke. Then, they erupt in laughter. In another scene, Ruslan (who likes “current” jokes) plays Alexander Lukashenko, the Byelorussian president. After he won the elections, he says, “Dick Cheney called to congratulate me. He invited me to go hunting …”

After the Greeting, the Illegals are in third place. But this is no time for distress. They have to prepare themselves for the improvisational Warm-Up — what Alexei calls the most telling contest in KVN, as it allows the participants to show off their true ability in spontaneous comedy. With only half a minute to think, the teams have to answer each question as wittily as possible.

“In the last Winter Olympic Games, the athletes from Zimbabwe did not win any gold medals. Why?” reads out Kaminskiy.

The Illegals stand in a circle, whispering, laughing, and nodding. Finally, Ruslan approaches the microphone. “That’s because in the last Summer Olympics, Zimbabwe’s diver died of happiness when he finally saw water!” The audience cheers loudly — nothing like a bit of dark humor to please the Russians. After several questions, the judges once again reveal the score for each team. The Illegals move up to first place.

The next and last contest is the Homework. The Illegals have constructed their Homework performance around the childhood of each of the four members. First, Semyon announces that when he was a kid, he wanted to be a banker. In the bank, Semyon offers his customer (Ruslan) a $100,000 credit line.

“A hundred thousand?!” cries Ruslan. To the music from Pulp Fiction, he pulls out a gun and points it at Semyon. “Attention, everyone, this is a robbery!” He turns to Alexei, another customer at the bank. “Don’t move!” he yells. “Or I’ll shoot his brains out!”

“You are bluffing,” says Alexei, calmly.

“Why the hell am I bluffing?!”

“Because he doesn’t have any brains.”

After Semyon is dead, Alexei flees the bank and Ruslan hides from the cops under Kaminsky’s podium, where he finds “a remote control for the judges.” Suddenly, a newscaster — also played by Alexei — interrupts with “breaking news from the scene of the robbery.” Ruslan, it turns out, is a correspondent sent to cover the robbery he has just committed. Smugly, Ruslan says that no one has seen anything. “There is only one witness,” he says, pointing the gun at KVN’s host in the corner. “But he didn’t see anything, either.”

In the next scene, Paul comes out onstage to confess that he always wanted to be “a tall, broad-shouldered blond,” rather than a skinny redhead. At least he has acting talent, he says, and the Illegals break into the scene from “Beauty and the Beast.”

The final scene is from the childhood of Alexei and Ruslan — two thickheaded thugs.

“I can read thoughts,” says Alexei.

“People’s thoughts?” asks Ruslan.

“Yeah, people’s … c’mon, help me out!”

Ruslan raises a cardboard sign and Alexei proceeds to read it. “Thoughts,” the sign says.

When Ruslan ends up robbing Alexei, Paul and Semyon emerge in police uniforms and arrest them.

“And that is how we all met,” concludes Ruslan, as they take a bow.

Tonight, there is nothing stopping the Illegals. They have the charm and the energy, and they are prepared. The audience loves them. Most importantly, the judges love them. Tonight, the Illegals finally win.

Now, they only need to survive the after-party.

Update, August 3, 2013: Edited and moved story from our old site to the current one.

Sasha Vasilyuk Sasha Vasilyuk is a writer based in New York City. She was born during a cold Russian winter and grew up in the golden hills of the San Francisco Bay Area. Her essays and articles on art, culture, business, travel, and love have been published in the Los Angeles Times, San Francisco Chronicle, Russian Newsweek, Oakland Tribune, and Flower magazine. She received the 2013 North American Travel Journalists Association silver medal for her Los Angeles Times cover photo "Barra De Valizas." She is currently working on a collection of essays about her year-long solo journey around the world.

Demonstrating an intolerance that is noxious, bizarre, and antithetical to living in a globalized world, the founder of PraiseMoves – a recently concocted “Christian alternative to yoga” – is demonizing yoga, of all things. PraiseMoves founder Laurette Willis was, apparently, stunned to learn that yoga was related to Hinduism, and now decries the practice, suggesting that the mental components of yoga can lead, apparently, to something approximating possession: “If there's nothing in your mind, you're open to all kinds of deception… While I don't believe Christians can become possessed, I do believe we can become oppressed by demonic spirits of fear, depression, lust, false religion, etc.”

While the movement’s idiocy may neuter its effectiveness, the motivations for PraiseMoves are both destructive in its encouragement of religious division and demonization as well its curious inability to acknowledge religious dialogue and shared religious practices that have evolved through inter-religious contact. If Ms. Willis were to be told that the Christmas tree is a practice that has rich pagan roots, she might be nudged to reconsider her intolerance. Although factionalization and the rhetoric of religious and ethnic division has gained currency and publicity, Ms. Willis would do well to be reminded that religious practices neither developed in a vacuum, nor are they static: they are dynamic processes that have developed through intellectual exchange – polemic and violent as well as syncretic and peaceful – both within and with other faith communities.

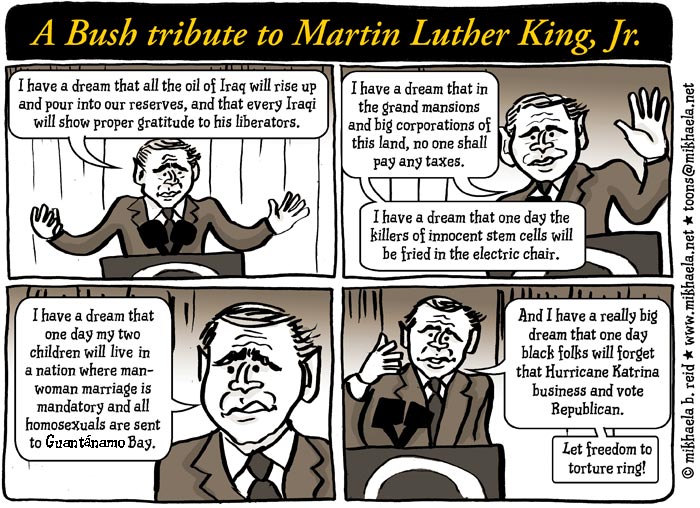

Detroit’s transition from past to present.

Detroit’s transition from past to present.

Concept

As technology spreads into the future, the obsolete are left behind. New things are created, while past creations decay. Nature begins to take apart what man once struggled to assemble. There is a threshold that is hard to pinpoint, when a manmade object becomes nature again. The difference between the two becomes blurred, and the beauty of this transition becomes visible: Concrete cracks with plant life. Iron and steel bleed rusty stains. Years of paint stratify walls. Wood warps and buckles to the elements. Trees grow upon the tar roofs of skyscrapers. Detroit is this transition.

Through the RELICS installation, man once again alters nature by extracting these objects, interrupting their return to the earth, and using them to create a contemporary museum of natural history. Patrons of this reliquary room sensually engage the history of Detroit, encompassed by energy and information. The viewer is overloaded by input, not unlike the artist’s own experiences while exploring forgotten sites. The senses are flooded, and one becomes fully aware of his/her surroundings — in the present moment — triggered by objects of the past.

Like everything and everyone, Detroit is moving and changing through time. Transiting cycles of birth, death, and rebirth; the City is our creation, and therefore, reflects our behavior. In the 300-some years since being named “the strait,” Detroit has gone from pure marshes and forests teeming with wildlife, to expanding farmland and industry that expended and veiled the fertile ground, to a state of post industrial wasteland with a waning population. Inhabitants have steadily fanned out of the core in a concentric pattern, leaving the civic center for nature to reclaim with infinite persistence. Now, a state of renaissance and rebirth is blossoming in the city’s core, and the natural cycle continues. The RELICS installation attempts to capture this state of transition and present the viewer with questions regarding art, history, and time — especially the dramatic changes over the last 100 years. How long, in this ever-changing landscape of our present world, does it take for something to be forgotten?

RELICS aims for a communication with viewers regarding what we, as civilized creatures, are creating, destroying, and leaving behind. It is meant to spark reveries and inspire conversation with strangers, and simply, to overwhelm viewers with the sheer mass of information, memory, and energy generated by thousands of relics of the future.

Logistics

At last count, over 400 wooden “boxes” make up the reliquary walls that create this installation. Each box measures 18” x 18” on the face, with a 12” depth. The boxes are made of medium-density fiberboard, 6 tons of it, and assembled in a chasing pattern with wooden screws and glue. The content of each box is secured by a variety of adhesives and hardware, whether recessing within the cube or protruding beyond the face. Each box rests upon those below, and is secured to the others and a supporting wall (unless free standing). Box construction places all weight upon the vertical boards, with added strength from wall to wall, or box to box pressure. Weight of individual units varies from about 10 to 100 pounds, with the heaviest being in the minority. The entire installation is modular and adaptable to any space, utilizing each site individually, but a large area with high ceilings is ideal. The boxes are open to the elements and human contact — naturally, they may change through travel and exposure. Some have been sold, others have been destroyed and/or recycled, and new boxes continue to be created. The installation is reconfigured and updated according to location and theme; hence, a detailed architectural plan of the potential exhibition area is necessary to determine the size and dimensions of this reincarnation.

[ Click here to enter the visual essay ]