I had a nightmare as a child, where goblins marched through the snow in step to the slow, steady rhythm of their drum, and the line of them extended way up into the mountains. Now, when I put my ear to the pillow, I can hear the sound again, and I remember them coming through the walls to get me.

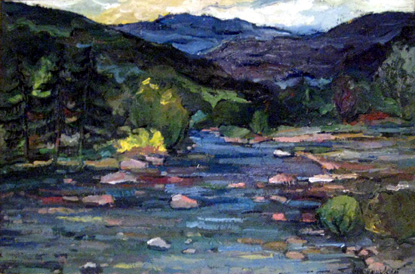

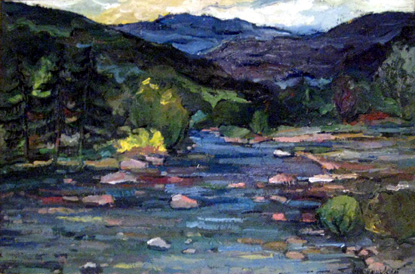

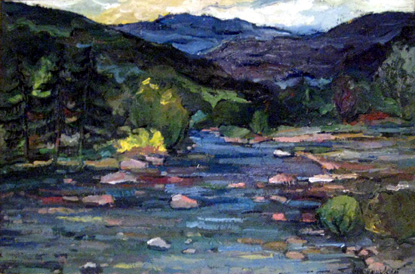

A large, slow-moving river runs through the center of my new life. I am a scholar now, not a soldier, and if successful, my achievements will be noted here and there in obscure academic circles. Dead leaves float in clusters along the banks of the river, just below the surface of the water, and a cold wind blows waves that lap the stones along its shore, and the dead leaves bob with the waves. This was where, months earlier, we met, and she refused to speak to me after I told her I’d been in uniform. She said she wished I hadn’t told her. I said I was thinking the same thing.

She’d been embarrassed, I think, by her anger during our introduction, and after months of polite smiles and quick hellos, she apologized. I told her she didn’t have to. She apologized again and said she hoped I didn’t hate her. I told her I didn’t, and when she said she didn’t believe me, I asked her to dinner. “If I behave strangely,” I told her, “it is only because I’m nervous around beautiful women.” I was glad to have been over there, I said, because I tried to be noble, and someone else might not have even tried. She asked if I had any photographs. Looking at smiling soldiers posing with guns, she said she’d seen enough before we were through with them. She would not look at me just then.

I think it is good to believe in things, meaning, to not believe in nothing, since already there is so little worth fighting for.

I come to my empty apartment wearing a sweater and the warm scarf she knotted around my neck the night before her return to Gaza. Two tea bags rest on my journal as a reminder to write about her. Being a humble woman, she didn’t throw them out after boiling them in water for us. They are dry in my fingers and smell of mint. The tea leaves crumble in the bags. She asked me if I’d ever been hungry and I told her how much weight I lost in training once. She was glad. I told her life is extremely short and she told me we are from different worlds. When she removed her scarf and wrapped it around me, I told her to keep it, because she wasn’t used to cold weather. Already, it was a harsh, dry cold that grabs your fingers and ears as soon as you step outside. She told me that she has hot blood and didn’t need it. I said I believed her.

I had felt happy to be alive again, taking refuge with her from the isolation of winter. Her bones seemed as thin and frail as a bird’s. I’d find her at the bar and sit beyond her circle of visiting artists. She could look so casual, glowing with heat, cigarette and wine, her curls in disarray, the burden of her compassion for this world hidden in the way she looked people in the eye and judged them for kindness. Few, it seemed, looked back.

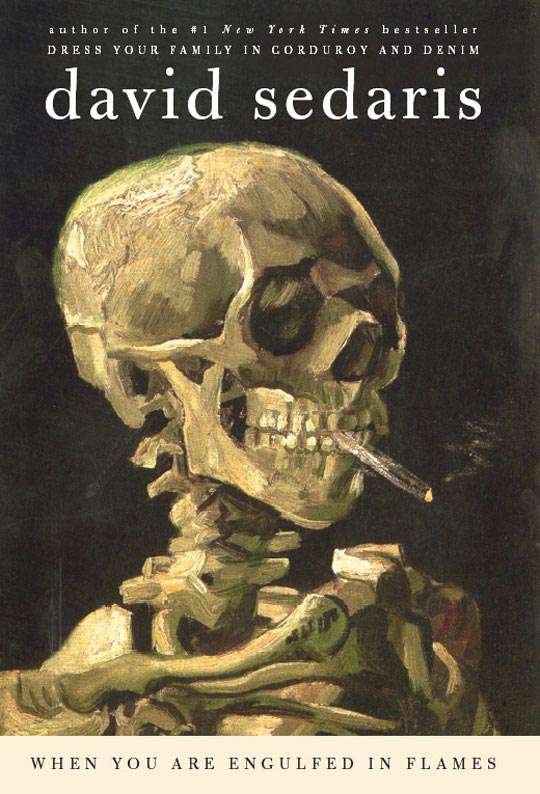

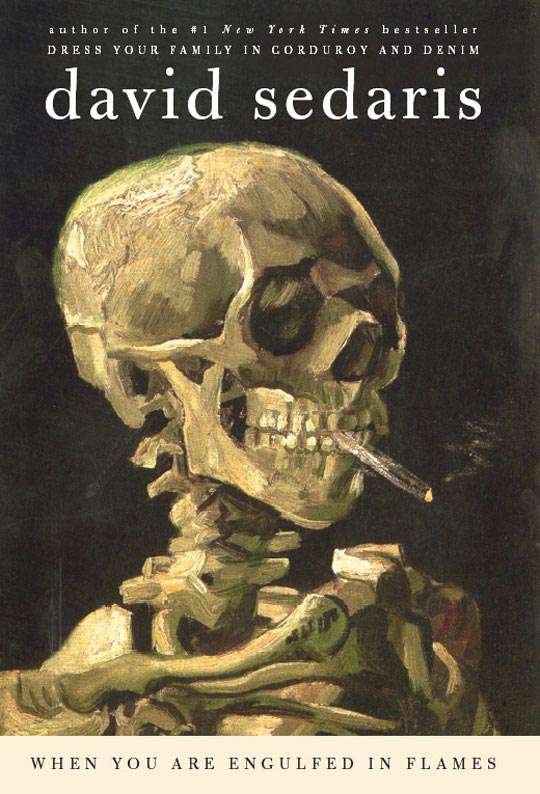

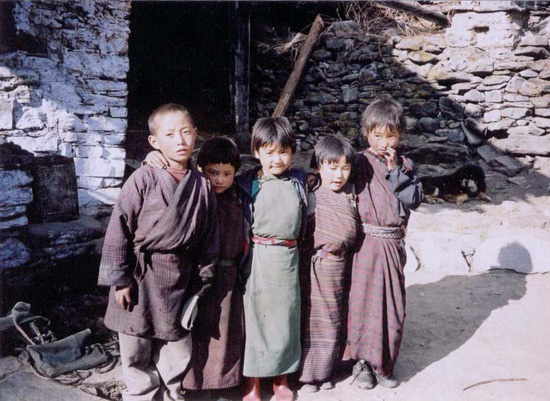

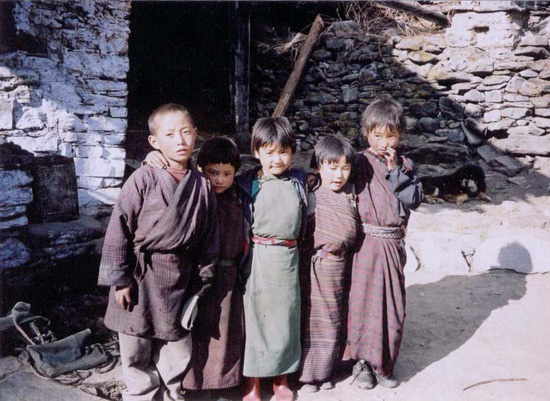

She gawked when I showed her my home, said not even a good woman could save my children from extravagance. (I’d never considered myself this way.) She asked how to use the stove. I told her I didn’t want her to leave, that she should find a way to stay at the university, to extend her visa. She told me how confused she felt. I told her she is still young. She talked about her family. “You must love them,” I said. She told me I’m a good person, and I said she doesn’t know me very well. She said she wanted to see the inside of a prison, and I told her she is still young and shouldn’t be rash. We never had enough time to finish understanding one another. I told her about the paintings on my walls — about the one of the house blending into the pale mountains behind it, the home of my grandparents and place of my childhood.

That was where I knew all the stones for a half mile up and down the mountain stream and had given them all names, where hemlock needles would spin through the curls of fast-moving water, and, in places where the stream was still, one could crawl to the edge of a boulder, peer over it, and if the sun didn’t cast your shadow over the water, faces of minnows would appear below the surface.

At night, in the mountains, the goblins came at me but couldn’t get through the walls, so they would bend them, and objects from across my room would suddenly be right on me. They would whisper to me and then jump back to the other side again, and the walls would bend, and my grandmother would squeeze me against her and tell me everything is okay, that there is no drumbeat inside of my pillow, that it is only the beat of my own heart. My grandmother would sing Ukrainian lullabies and I could feel the goblins scratching themselves inside of my skin.

We cooked dinner and she asked me to play my music. She asked if I had any music from my family’s old country. I didn’t realize how much this meant to me. I told her they were singing about freedom and she told me that I must be very proud. I was. Many of hers, she said, are ashamed. Different worlds aside, I asked her to marry me. She agreed. If we are both single a decade from now, we will find each other and marry. “And living,” she added. I asked if she’d like to live in the mountains, and she told me it’d be up to me. I told her I’d try to remain unsuccessful so our children can grow up humble. I wished her great happiness and she told me to wish her great courage instead.

They came through the walls again and marched back and forth in my room. Back and forth, seeing nothing with their blank fish-eyes, and they marched on their feathered legs and feet that look like human hands, their horns carving furrows in the plaster of my ceiling, and I could see their severed limbs.

When I was a child, I was told to write because it was healthy. They said write that you don’t know what to write, because it’s healthy for you to have an outlet, because you have no sibling to talk to, few friends. But the dreams persisted. I learned to slip outside at night to take walks, and I’d wait for the dawn before sneaking back to my bed.

Write your secrets, they said. The woods across the stream were dark. The trees were older there and rooted in the seep bank. Some bowed so far toward the water, the tops of them touched the surface. The only way to cross came in the autumn, when the water was lower, and even then, one had to be an expert of the rocks. One had to know which way to hop so as not to strand oneself, or to unexpectedly step on a rock widely known among experts for its wobble. This knowledge was my secret. At night, the noise of the stream pushed away the drum.

I told her about the ringing in both my ears — something I’m learning to live with — and how I missed the sound of quiet. She lay with her ear to my chest and told me my heart sounded strong. She asked if they could still call me, if I’d go back, if I’d refuse.

My new is life is so easy, I feel guilty. I told her I would go. Of course I would go. Duty, I said. “Don’t,” she replied, “because we will kill you.” We. I told her I believed her. Her body was thin as a match stick. She said we had too much to say to one another before she had to return home, and I told her to write it all down.

When I told her she must be tired from carrying such heavy things all the time, she startled like she’d been doused with water, and touched me for the first time — the promise of something worthwhile, permanent. I asked her to put the heavy things down for a little while and sit on the swings with me. We’d gone for a walk. The stars were out. I told her I didn’t believe in God. She told me how confused she was. I told her I could spend all night telling her stories about the house and the mountains, and she told me she’d listen.

In the summer, I could skip one of every five stones off the surface of the stream and have it bounce onto the opposite bank. Scouts. In the autumn, I would gather the ones that made it and return them to the water.

One of the goblins stopped his march, looked straight at me with the jelly eye of a fish. I felt him crawling and twisting underneath my skin, his bones clattering against my own. I don’t know why they hate me.

“I like drinking and sex,” she’d told me, “but when I think about my father, I am ashamed.”

I’m alone now with my paintings and my heart, and I fear the truth will make me a very lonely person. At some point I became aware that the puzzle of the Earth did not quite fit together, and the goblins’ drum comes to sound like the question “why” hammering in my temples. I want to stop thinking, and yet: Why! Why! Why! Why! Why! The frail patches of logic I construct over the fault of the Earth collapse the instant they are created, and I fear the pressure is building somewhere deep, somewhere beneath the surface of the ocean, unseen, unheard, building slowly in the darkness. A pressure in the depths that may yet come roaring out from the darkness and toss the ocean in a wild and unpredictable direction.

At night, I’d pull sneakers over my bare feet and find peace in the chilly air, electric with the chants of unseen creatures. The road between my grandparents’ house and the near bank of the river looked like a striped serpent heavy in its slumber. A few paces off the asphalt, everything was dark. I would stand in the dewy brush, listening to the night, my eyes groping the darkness. Slowly, black and blacker things distinguished themselves in the shadows, and I’d feel for the path under my feet and follow it toward the gurgling stream, where stones shone white with moonlight and the water raced eternally between them. I’d watch the far bank, and the goblins’ drum would seem very far away.

“I’ll see you in 10 years,” she told me. Insha Allah.

I fell into the stream once as a child, when summer was still in bloom and I, too anxious to wait for the fall, attempted to reach the dark woods. I burst back up through the surface, sucking the sweet air, my sweater heavy with water, pulling me down, the sound of falling water all around me, skin bristling with cold, and my eyes flooding with the moon shadows of leaves on the water, and the dark woods alive in the starry night. I wanted the moment to last forever, like a painting. It was then I decided to follow the sound of the drum.

When I wrote, telling her they were calling me back, and that I would be going, she said good-bye.

Roman A. Skaskiw

Dear Reader,

In The Fray is a nonprofit staffed by volunteers. If you liked this piece, could you

please donate $10? If you want to help, you can also: