- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

Afghan president Hamid Karzai is currently reviewing the law, after much protest from the international community.

The law aimed at the minority Shia community prohibits a woman from leaving the house without her husband's permission and says that a wife cannot say no to her husband when it comes to sex.

Extremism is making a strong comeback in Afghanistan's government, and it is no secret. Otherwise, how can you explain a law that legalizes rape? Not only is the government in Kabul incompetent to deal with extremist mullahs and religious leaders, it is also inept at dealing with the resurgent Taliban.

According to UPI , the Taliban recently murdered a couple for eloping. The woman defied her parents and ran away with her lover. Her parents reported the incident to the religious militia and the young couple was publicly executed.

Friends of my mother are coming to New York for the first time ever. Unbeknownst to me I was nominated as their go-to gal for all things Big Apple. Their itinerary includes super fun things like Times Square and the Empire State Building. Boy, do I LOVE Times Square.

Note: the aforementioned is for parental use only. My grand tour of the city begins and ends by handing them a map and a MetroCard. Rule 31-5.4.6 of my New York City Life Continuity Plan is still in effect, which clearly states that, to improve upon Dorothy's line, there's no place like my couch. Though there is a provision in the event George Clooney should need a personal tour.

So I've been sending my mother's friends all sorts of helpful advice about taking the subway. Number one (say it with me): No eye contact. (This will be hard for them. They are from the South, where it is polite to look people in the eye. In New York, it is considered an act of aggression.) Number two: Ditch the tell-tale I'm-a-tourist white sneakers. Number three: If a train car appears empty, there's a damn good reason.

I emailed them link to the subway map. "This is a little overwhelming," they wrote back.

Why yes, yes it is. Even back in 1904 when the first subway lines were completed, I wouldn't be surprised if one sandhog — nickname of the men who dug the tunnels with pickaxes and shovels — had nudged another and said, "Bet you a nickel they'll never figure out how to get crosstown."

I suggested to my mom's friends they could look to Sammy Sosa for inspiration. Not that Sammy Sosa. This Sammy Sosa, age 5, tired of waiting for his mother, went upstairs to the elevated platform and boarded a 1 train in the Bronx by himself. While his mother frantically called the police, who in turn searched the neighborhood and called in helicopters, little Sammy calmly rode the 1 train, all the way to South Ferry — 33 stops. The police had notified the MTA, just in case, and a conductor noticed a little boy who didn't get off the train even though it was the end of the line. The conductor said, "He looked like he was having a good time, not a care in the world, like it was just another ride for him."

May my mother's friends be able to ride the subway just like little Sammy Sosa. I'll be there for moral support — from my couch.

It seems as though every Easter Sunday has been bright and crispy clear. Although we had a heavy rain storm yesterday, the sun faithfully shone through the window this morning as my cats soaked in the warm rays while watching chirping sparrows tease them on the fire escape rail. The painful puddles of yesterday dried up, and the bright blue sky smiled at me with hope.

"You must look forward," she said.

So in this spirit, I planted yellow and orange snapdragons to remind me how I can turn bitterness into beauty if I choose to.

I am reminded of my neighbors' seder last year, where I had the privilege of experiencing bitter parsley dipped in salt and sweet charoset smothered on matzo for the very first time.

The bitterness and sweetness of life is a universal theme. Every spring can be a renaissance of what we want most in our lives. If I may, I'd like to leave with you with Robert Frost's A Prayer In Spring:

Oh, give us pleasure in the flowers to-day;

And give us not to think so far away

As the uncertain harvest; keep us here

All simply in the springing of the year.

Oh, give us pleasure in the orchard white,

Like nothing else by day, like ghosts by night;

And make us happy in the happy bees,

The swarm dilating round the perfect trees.

And make us happy in the darting bird

That suddenly above the bees is heard,

The meteor that thrusts in with needle bill,

And off a blossom in mid air stands still.

For this is love and nothing else is love,

The which it is reserved for God above

To sanctify to what far ends He will,

But which it only needs that we fulfil.

I see the grubby white utility van as I pull up beside it at the red light. Heavy aluminum ladders are latched onto its sides, like saddlebags weighing down a workhorse. Morning rush hour jams and crams the intersection at Irving Park and Clarendon where the buses stop and load up more commuters. All of us hurry to squeeze onto Lake Shore Drive. We are anonymous, autonomous rats, racing to work.

Quickly, I glance over at the van driver and I am surprised to see that he is putting on lip balm. I don’t know why I am surprised. The tail end of winter has whipped Chicago in the face and it still hurts. I watch as he carefully lines up the lid to press it back on the tube. And I think, I know that, I know that moment. I’ve done it a hundred times myself, determined not to dent the waxy balm with the cap’s edge. And if I slip and there’s a scrape, I apply one more coat to try to smooth out the gouge I’ve made.

I watch as he rubs his lips together. I rub my lips together too. Mine are dry and sore. I imagine his are smooth and soft. And in that moment, all anonymity slips away. He is familiar to me. We are the same. Just skin. Chapped from the long months of winter winds.

Manama is not a very glitzy city when you compare it to cities in the region, but it is charming. Sadly the waterfront areas are being rapidly urbanized, making them look like an ugly replica of Dubai. And there were lot of South Asian laborers around the city. I met some from my native Nepal.

Along with its pragmatic attitude on women's rights and their participation in public life, Baharain has gone a new way on Jewish-Muslim relations.

The New York Times reports that "It's O.K. to be Jewish in Bahrain." It is no secret that in the region and around the world, Jewish-Muslim relations have suffered because of Israeli-Palestinian conflict, but Bahrain's King Hamad bin Isa Al-Khalifa — a Sunni Muslim — has taken steps to embrace the country's Jewish minority.

But not everyone is happy. Some see the King's move as a way to keep America — Bahrain's ally — happy, and some question the king's tolerance towards Jews and discrimination against the native Shia.

The bundled man hurries onto the train. Sloppily scooting through the aisle, dangling his umbrella from his wrist. Wet nylon droops from its spokes and the umbrella spins. The floor is wet, water in the ridges, and the bundled man slips slightly, skimming the teenager in the seat in front of him. The umbrella spits and splatters the back of the kid's neck. "Sorry," I hear the man say. I hear him say this from the other side of the train. But the kid can’t hear him, not from a foot away, because he's plugged into his iPod, which I can also hear from the other side of the train. The look of adolescent disdain on the kid's face is wasted as the man sits down behind him, oblivious.

Slowly, the kid reaches up and flips the droplets off his neck with the back of his hand. Flip. Flip.

More riders tumble onto the train. The aisle fills with dripping wool coats, and I adjust my bags to keep from getting soggy. In the process, I bang my bag into the woman seated next to me, hitting her purse. Reflexively I say, "Sorry." And the woman, also plugged into her iPod, hears me, recognizes my gesture at least, and without the effort of air behind her words, mouths, "It's okay." But it's obviously not okay because I hear her sigh a put-out sigh and clutch her purse as tightly as she purses her lips.

My discarded apology flutters to the floor, and the standing passengers grind it into bits beneath their feet.

No one can hear anyone anymore, I think. iPods, cell phones, bluetooths (or is it blueteeth if it's plural?). All of us putting plastic up against our ears, or shoving it down inside, a barrier between our eardrums and another being's voice. Yeah technology, more ways to communicate, to stay in touch, to be connected. Whatever. Screw it, I think, pulling out my iPod and plugging in.

At Fullerton, the woman next to me tries to squish past. I don't notice that she wants out because I have my music up loud. I barely have time to move my knees let alone stand, and her adult disdain isn't wasted on me.

Once she's gone I get a new seatmate. He's soaking wet, denim darker from the shins down. Rain rolls down his leather jacket and I follow the beads as they travel the length of his sleeve. He's holding a Palm Centro, like mine, but black, and typing furiously, thumbs tap dancing on the tiny keys. I assume he's playing a game, Tetris or Bejeweled, and think, yep, just another way we disconnect. But then I get a good look at his screen.

I smile when I read the subject line — Re: Apology.

Still waiting…

The peeps inch closer to a commuter.

The peeps, tired of waiting for the train, decide to commit hari-kiri.

Into the Light is a collection of images bound together by their impressive use of light.

[Click here to view the slideshow]

Saturday, April 14, 2007

Late morning

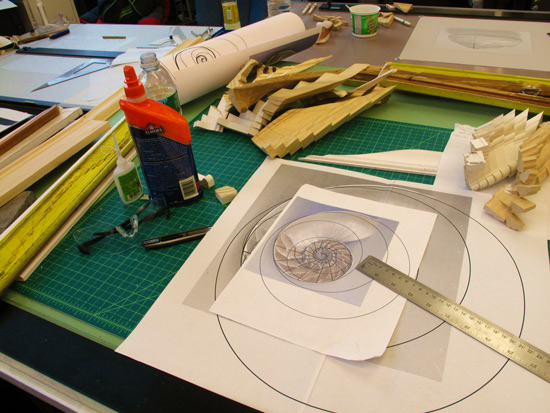

Approximately 240 hours until Final Review

Sunlight floods through skylights in a vast loft and washes over a scene of filth and chaos. Gutted Chinese food cartons, crumpled sandwich wraps, abandoned ice cream tubs oozing at the seams, razors, rulers, energy drinks, sawdust, tape, foamcore, and glue lie heaped and scattered across 40 tabletops. It is only the occasional odd structure, delicate and meticulously crafted, or the intricate drawings of complex geometry, or the laboriously worked models tossed in with the debris, that reveal this to be a place where architecture is conceived and designs struggle to find form.

This morning, in the far left corner of the studio, half a dozen young men and women are working quietly. They are first-year undergraduate students at the Pratt Institute’s School of Architecture in Brooklyn, New York. In just 10 days they have their end-of-the-year final review, where they will present their semester’s work to a jury of professors and professionals and be judged for the sophistication of their thought and the beauty and quality of their craft.

Ezra G., 19, sprawls on his stool. He stares at his laptop and sketches a complex diagram on the paper covering of his table.

“Okay Ezra, looks like you’re going to be first,” says Evan Tribus, instructor for one of the four classes that share this studio space. Tribus has come in the past several Saturdays, in addition to class time, to offer his 10 students what assistance and advice he can. He circles Ezra’s desk. So far, Ezra’s model is a sheet of intricately interconnected paper cones that look more like a scaly pelt than anything pertaining to a building. Next to it are strewn an abundance of sketches, diagrams, and equations.

“So, these are your underwater viewing chambers?” Tribus asks, peering at one of the drawings.

“Yeah …” Ezra drops the pen, wipes a hand across his face, and blinks hard. He is tall. He has wide shoulders, hair the color of pale ale, and carries himself with the loose-limbed confidence of an athlete. He is from the mountains of North Carolina and knows how to kill a deer, rebuild a motorcycle engine, and survive in the woods for days if necessary.

“Show me again how you’re going to accommodate the ocean currents,” says Tribus.

Ezra pokes his model impatiently and explains something of the engineering principles behind the structure it represents — a building of sorts that would float on the ocean surface, flush visitors through a dizzying array of water tunnels, wind halls, and pitching chambers, and guarantee them a “nauseatingly visceral” experience sure to inspire meditation on such topics as control, fate, fear, and liberation.

Tribus nods solemnly. “Okay. Great. But looks like you’ve got a lot of work to do.”

Several tables down from Ezra is Eunice K., also 19. Her desk is littered with gritty, graying pieces of paper that have clearly been glued, pulled apart, and re-glued multiple times. For some reason Eunice has replaced her stool with a shopping cart. Seated in the cart, her head barely rises above the table’s edge. Tribus surveys her table.

“I don’t have any new work,” she says quietly.

“Nice seat,” says Tribus. “You want to talk about that?”

“There’s nothing to talk about.”

“Look, your drawings are really nice. Make sure you present them at final too, okay? It’s important to show your process.”

The studio door swings open. A young man in shorts and flip-flops huffs in, weaves noisily between the desks, and drops his backpack with a thud by the table in the corner.

“How are you, Eric?” asks Tribus.

“Bad. Stupid upperclassman. Totally took over the laser cutter. They wouldn’t let me use it at all.”

Like most other students, Eric has pictures, notes, and mementos of personal significance around his desk. Among his are photographs from several of his high school’s theater productions. He loves theater. He thought he might want to study set design, but his father graduated from Pratt’s School of Architecture, and his older brother attends currently. All things considered, Eric explained, he decided that architecture maybe was the more practical field to pursue.

The other students’ models are fanciful structures, scarcely distinguishable as architecture, but Eric’s is distinctly a building. It has a smooth floor, a hint of stairs, and a watermelon-sized domed ceiling.

There is a long moment of quiet while Tribus gazes at Eric’s model.

“Your dimensions are all wrong,” he says eventually. “You want these to be stairs, right? Do you see? They’re way too steep.”

“Mmmmmm,” says Eric.

There are apparently other problems too, something to do with the whole concept of the piece. Tribus urges Eric to consider the viewer-viewee relationship more carefully, to think in terms of feeling rather than literally, to try to convey a mood. Eric glances out the window. Tribus shrugs. “Look … I can’t make you do it, but I think it would make your project better,” and he moves on.

Charrette is a French word meaning chariot, wagon, or cart. According to legend, in the 19th century at L’Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, students’ work was gathered up and whisked off for review by means of a horse-drawn cart. Students working frantically until the last minute would leap onto the cart and make final changes en charrette as it trundled to its destination. Now, for those in the design profession, the term refers to final crunch time before a deadline — usually a period of sleepless nights and frenzied productivity.

In April 2007, all architecture students enrolled at Pratt were in charrette, getting ready for their respective classes’ final reviews. For first-year students the pressure is particularly acute. The relentless workload and harsh critiques of the first year are designed to cull out any who might prove insufficiently bright or dedicated to pass in the program.

“Look, if I had my way,” Tribus says one evening over dinner at a restaurant near Pratt, “they’d never leave the building. I want them there all day, every day. If you sleep, sleep there. If you need something, order in.”

Tribus is a smallish man with a tidy goatee and a sharp, intelligent gaze. He stares at me over the noodles.

“You think I’m kidding,” he says. “I’m not.”

Charrette, he tells me, can be a remarkable time too, as long as people engage in it wholeheartedly.

“Charrette is a really special time. The sheer fact of so many people working together in a contained space, so intensely … it generates an incredible creative energy. Being in that community environment helps. You can get so much done. It’s a singular, really amazing thing.”

He recalls warmly the friendships forged and the euphoric moments of exhaustion and achievement from the charrettes of his school years.

But in architecture, he explains, the quality of one’s work correlates closely to the sheer quantity one produces. Students must be able to demonstrate their thought processes through the work they do, and be able to justify all decisions. The more work one does, the more thoroughly one thinks through the nuances of one’s project, and the better one can defend it at review.

“You can never have enough work. You could always produce more. And so you should.”

Sunday, April 15, 2007

Late night

Approximately 206 hours until Final Review

Four students bend into the puddles of light at their tables. Outside, lightning flickers and rain pours down steadily. Wet clothes drag on a rope strung between two columns. Reggae thumps quietly from another corner of the studio.

Eunice is perched on the edge of her cart. When she grins, a deep dimple punctures the left side of her chin.

“I got it to work!” she says triumphantly. Last night, she finally figured out how to connect the folded paper pieces that are the building blocks of her model. Now they spread in a stiff froth across her entire desk.

“This is a desert landscape,” she explains. “My architecture grows here, at the end. The idea is that you go from this arid, harsh landscape to a cool, really nice space, where you can relax. Every individual can rest, however they want to. It’s kind of a journey, I guess.”

Eunice tells me how she struggled for a long time to get her model to behave. She became frustrated, then lost enthusiasm for her work.

“Sometimes you get to a certain point, you think you’re doing well, then you look around and it seems other people get it so much faster, are doing so much better. And then you have a doubt here …” She touches her heart.

For some reason, Eric never bought a desk lamp, so his corner of the studio is dark. I don’t see any progress on his model, but he says things are going well.

“It’s kind of an amphitheater,” he says, then rolls his eyes. “Though I’m not supposed to call it that anymore. Tribus says it’s too literal, or something.”

Thursday, April 19 / Friday, April 20, 2007

Very early morning hours

Approximately 103 hours until Final Review

Charrette has a smell: rancid food, the tang of fermented liquid — also the students. They smell of unwashed bodies and hair, dirty clothes and feet. The reason most students wear flip-flops or pad around in socks, I’m told, is to avoid “swamp foot”: that particular condition when overlong confinement in a shoe brings on massive skin peeling and odoriferous decay.

There are many people in the studio tonight. Lights blaze. Behind a barrel overflowing with garbage, someone is sleeping on the communal couch. The couch looks like the well-used toy of a huge canine. An entire side has been ripped off, trailing stuffing. This was done on purpose, I’m told, so that tall people could sleep comfortably, too. Grueling sleep deprivation is the most renowned — indeed celebrated — aspect of architectural training.

Ezra has been absentmindedly slicing up the paper on his desk with an exacto knife, ruining the intricate drawings laid down there over weeks. On the skin between his thumb and forefinger he’s written a list of numbers that remind him of the tasks he wants to accomplish, and roughly how many hours they’ll take.

“So I know if I can take a break or not,” he says wryly. “Sometimes I fall asleep on my desk. That’s kind of comfortable,” he says. Often he sleeps under it and stays in the architecture building four or five days at a time without going home.

Patrick, a mild-mannered and diligent student, 19 years old, stands at his desk gluing together long slivers of basswood. The wood is a cream color except along the edge where the laser cutter has burned it dark brown. The pieces look like thin slices of portobello mushroom. Patrick looks like a soldier from a PBS documentary about the Revolutionary War. He is lean, has lank brown hair pulled back into a walnut-sized nub at the nape of his neck, and earnest, thoughtful expressions.

When I comment on all the empty liquor bottles scattered around the studio — and there are many — Patrick smiles lopsidedly.

“We’re trying to have a college experience too, you know.”

“You should have been here last night!” calls out Evan, an 18-year-old who could easily pass for 13. “We played this crazy drinking game … like with how fast you can eat saltines … and Patrick did these tricks …” He pauses, concentrating for a moment on the tiny bits of wood he is gluing together with the aid of dental tools.

Sunday, April 22, 2007

Early afternoon

Approximately 44 hours to Final Review

“Dude, you left your phone here,” someone tells Eric, who has just arrived and slipped quietly behind his desk.

“I know. I realized that when I got home last night and wanted to call my mom.”

“You were going to call your mom at 4 a.m.?” I ask.

“Well,” his smile is strained, “she did say to call if I ever needed anything …”

“What did you need?”

“To talk to her,” and he ducks his head.

Ezra is wearing clean clothes and is freshly shaven, but he looks exhausted. He slumps at his desk, his back curved like a question mark.

Patrick is trying to tease out pieces of wood carved, imperfectly, by the laser cutter. A delicate piece snaps. He groans with great feeling. He has made some extras, but not many.

“I didn’t make any extras at all,” says Eric. “Some of mine broke, too, and I had to glue them together. I guess my model will just have to have some seams in it.”

Brandon B. is perched delicately on his stool, teetering above the chaotic scrap pile of supplies and filth below his desk, gluing portions of his model to a blackboard and gossiping steadily with Julie, at the adjacent desk. Brandon is quick-witted and whimsically imaginative, but easily distracted. He stops gluing and happily explains his model to me. The concept is evolution, he says. At presentation he will show how a single geometric unit — the same one that ultimately succeeds in growing into a piece of architecture — could, with other rules governing its duplication, have petered out, turned in on itself, expanded uselessly and, in myriad other ways, failed.

“You know,” says Ezra, “that’s what my model last semester was all about.”

“Cool,” says Brandon, gingerly extracting his fingers, which have dried into the glue on his model.

“Yeah … it was about failure … success …. fate. You know.”

“Shoot! I got superglue on my lip again.”

At 3:00 p.m., Eric shouts, “Done! I’m done with my theater!”

“Aaaagh!” Patrick wails as another thin slice snaps.

Tuesday, April 24, 2007

Predawn hours

Approximately nine hours to Final Review

The studio is quiet. Eight from the class are there; Brandon and one other are working at home.

The only sound is the repeated swiping of blade on wood, where Eunice is bent over a long board, carving out the basic building blocks of her model. It takes four or five swipes along the same line to cut through the wood. Fifteen to 30 swipes per piece — that’s about half a minute for each one. Some pieces break. She needs at least a 100 to build her model. She wasn’t able to start before because she couldn’t figure the right dimensions. Ezra taught her a new computer program that helped, but it didn’t all come together until yesterday.

“I loathe my project,” says Ezra, staring contemptuously at the elegant paper sculptures and elaborate drawings scattered across his desk. “I really do … I don’t know if it’s the concept that sucks, or just me. The craftsmanship is shitty.”

Julie, a pretty girl who is rarely in the studio, always stylishly dressed, and who usually projects an aggressive self-confidence, slips through the main door looking completely dejected. Apparently an upperclassman kicked her off the laser cutter before she’d gotten the last pieces she needs. Her face threatens tears. She explains her story to her concerned classmates.

“What an asshole!” bellows Evan, who is still edging sharp slivers of wood around with his dental equipment, and everyone agrees.

Patrick is the only one who seems happy. He’s on his last drawing and exudes zealous energy. He wipes the paper with a flourish after laying down each line — his work is very clean and neat; the jury will like that.

Mysteriously, there’s a pile of balloons on Evan’s desk. Suddenly, Patrick puts aside his pencil and selects one.

“Let’s see who can blow up the balloon biggest in one breath,” he says.

Evan grins.

Eric looks up.

Kevin and Jon promptly rise from their tables and drift to Patrick’s.

“I got to see this,” says Ezra.

Everyone gets a balloon. Even Julie. Even me, and even Eunice, though she hesitates, momentarily undecided, glancing at the clock. She selects a bright yellow one.

“Ready, set, go!”

We stand in a cluster under the inky skylights. For a bright, hissing moment, nine lovely bubbles of color bloom just perfectly.

Sincere thanks to the Pratt Institute School of Architecture; Evan Douglis, chairperson undergraduate architecture; Evan Tribus, visiting assistant professor; and the students of the Arch 102.07 studio, spring 2007.

I’m a sucker for those Internet advertisements that promise a free iPod, laptop, or camera. I’m ashamed to admit it, but I’ve clicked on them enough times to know by now that what they promise and what they deliver are two different things. Usually you have to sign up for a few credit cards, maybe register for Netflix, and then spend $1500 or so on airplane tickets or home furnishings. So you do get a free iPod, but only if you spend $1500 first. What a bargain.

It’s a lesson that I must learn again and again: There is nothing in this life that comes for free. Everything must be earned, everything must be worked for and all must be built. There are no shortcuts, not in dieting, in exercising, in education, in relationships, or in anything else in this world. Yet it is human nature to search for an easier way.

This month’s issue of InTheFray features stories that explore the value of hard work. Sarah Hart takes a look at first-year architecture students preparing their final projects in Charrette. In The delicate art of Facebook snooping, Preethi Dumpala looks at how Facebook has made keeping up with former classmates, old friends, and ex-partners easier — and what this means. In my piece Tourism vs. Backpacking, I tell how my trip through Kashmir has taught me the difference between the two modes of traveling.

In Ashish Mehta’s short story Aliens, we are shown how the difficult moments of our childhood become the defining moments of who we are. Niclas Rantala presents photography that makes a powerful use of light in his slideshow Into the light. Finally, poet Lynn Strongin shares four poems in her series Lean over: there is something I must tell you.

In some senses, it is humanity’s desire for an easy way out that is behind thousands of years of technological development. Early farmers wanted an easier way to break the soil and invented the plow. The desire to move across the country quicker than by horseback drove the development of modern transportation. And the need for increasingly accurate counting and calculating machines resulted in the development of the modern computer. Yet each of these innovations was itself the result of hard work. There is no way around it: progress must be earned.

Aaron Richner I am a writer/editor turned web developer. I've served as both Editor-in-chief and Technical Developer of In The Fray Magazine over the past 5 years. I am gainfully employed, writing, editing and developing on the web for a small private college in Duluth, MN. I enjoy both silence and heavy metal, John Milton and Stephen King, sunrise and sunset. Like all of us, I contain multitudes.

It’s hard to know exactly where to begin with India. India is a contradiction. India is an ancient enigma. India is both a temptress and thief, modern and ancient, new and old, alive and dead. India will pay for the tuk-tuk to take you away from the train station just to sell you an expensive trip to Kashmir. India will take your picture and demand to be paid when you take hers. India will promise to not sell you anything and sell you something anyway. India will leave you to sit on the roof of the houseboat floating on a lake of shit, to watch the sun set and listen to the prayer calls. India will insist that there is no problem when it is clear that there is a problem. India will tear at your heart and she will restore your hope in humanity.

See what I mean? Where do you begin with that?

So forgive me if I start with something of which I am certain: I do not like airports. There are too many people asking too many vaguely accusatory questions, too many security checks, too many regulations, too many assault weapons, and too much waiting. I get uneasy, nervous, anxious, and I’m unable to relax. The domestic terminal of the Delhi airport, where my wife and I are waiting for a flight to Srinagar, in Indian Kashmir, does nothing to relax me. I am sitting in a thick knot of humanity, the scent of which hangs in the air around me. It wafts out from the strange and frightening toilets and floats through the lobby of impatient travelers. My anxiety is not eased when I have to identify my bags on the tarmac before they will be loaded on the plane. It is a jarring reminder that Kashmir is a disputed territory and terrorism is a very real threat.

I’m not sure what has brought us to India. I had a vague, idealized notion of a romantic India: a place of magic and wonder, where a young prince meets death, illness and old age becomes an enlightened ascetic. The United States refers to itself as the melting pot, but it is India where Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, and Christians all swirl together, mixing in a thick stew of 22 constitutionally recognized languages. Kashmir represented the crown jewel of this mystery and mysticism, a paradise on Earth, fought over by nuclear powers.

Srinagar, in the heart of the Kashmir valley, is famous for its lakes; there are sections of town with streets of water, and shikara boats ply the channels like gondolas in an Indian Venice. The interconnected lakes, Nagin and Dal, are ringed with houseboats and filled with floating vegetable and flower gardens. For centuries the town was a major tourist destination, but visitors to Kashmir have declined due to terrorism. Though tensions between India and Pakistan have eased in recent years, violence occasionally flares up. All of Kashmir is heavily militarized. Each intersection has two or three soldiers posted, assault rifles ready, and there are frequent barricades in the road made of barbed wire and sandbags. The devastating violence has left the people war-weary, ready for peace.

Lonely Planet India (LP) advises a traveler to not under any circumstances book one’s accommodations in Srinagar before leaving Delhi, because you will overpay for a houseboat that has been over-promised. LP warns travelers to not believe anyone who tells you that the tourist office is closed, that it’s somewhere else, or has burned down. My wife and I, with our week’s worth of experience in India, are certain we know much more than our guidebook. We follow the advice of a very kind tout who found us wandering around in the Delhi train station, confused and lost. He is nice enough to put us in a tuk – tuk and bring us to his friend’s travel agency.

"This tourist office is closed today," he says. "I will show you."

He knows a guy who can get us a “great price.” He is doing us a favor. At the travel agency we are shown photos of a beautiful, ornate houseboat floating on a pristine lake surrounded by the snow-capped peaks of the Himalayas. It looks like paradise. It is paradise, our travel agent assures us, and he will give us a bargain price. Just because he likes us. We pay up front.

We think we are clever, because this means we’ll have a ride waiting for us at the Srinagar airport. This is what you do when traveling as a Tourist. Your transportation is arranged for you, you have an itinerary, and everything is planned out ahead of time. There is a comfort in these certainties, because you do not have to worry about where you will stay, how you will get there, what it will cost, and whether you are getting a good deal. As a Tourist, your needs are catered to by someone who has done this before.

Mustaq is a tall, bronzed man with a loping gait and a quick, wide smile. He is easygoing and instantly likable. We chat about ourselves and about Kashmir as we drive to the houseboat, where we meet Hamid, the manager of the boat.

My wife and I envisioned ourselves exploring the streets of Srinagar by ourselves, stumbling across mysterious ancient ruins or maybe the Tomb of Jesus, or visiting a mosque. It is Hamid who tells us how it will be. We may have paid for our lodging, but we hadn’t paid for anything else. Because Kashmir is a disputed territory, Hamid tells us, we are required to have a guide with us at all times. Any tours we want to go on will have to be arranged through him. For a fee. Hamid sees our blue American passports and determines that we are like washrags filled with money that he must wring out.

"Americans and Saudi Arabians have all the money," he repeats several times as we discuss our itinerary, wringing, twisting. "They can afford anything."

But once we are through negotiating with Hamid, he and Mustaq make it clear that we are their guests, and Mustaq proceeds to treat us with the utmost of respect and care, attending to our every need.

Despite the heavy militarization of the area, and despite giving us the hard sell at every opportunity, Kashmiris are extremely friendly, always quick to offer a cup of their milky, cardamom-flavored tea. Pakistan and India may both lay claim to Kashmir, but the Kashmiri soul is fiercely independent. The Kashmiris we meet are a proud and happy people. When we meet someone, they invariably ask, "How are you?"; "Where are you from?"; "How do you like Kashmir?", in that order.

Kashmiris often say that they live in the most beautiful place on earth, and it breaks my heart a little bit every time I hear this. In addition to the smog that hangs over the mountains, the lakes and channels are clogged with pollution. Toilets in the houseboats flush directly into the lakes, filling them with thick, nasty sludge. The streets are thick with litter. The buildings are decrepit and decaying, like broken teeth. Despite all this, you can sometimes still see Kashmir’s beauty. The Mughal Gardens burst forth with fountains and flowers, the lakes shine like jewels when the sun strikes them, and the pride of the people who live there is humbling. It is painful to see this evident beauty diminished by a lack of resources to provide adequate sanitation.

We experience Kashmir as Tourists, riding from the Hazratbal Mosque to a trek in the Himalayas in a large, white SUV, like VIPs blasting through the streets of Baghdad. We are supervised every moment we are awake by either Mustaq, Hamid, or another guide. The few moments that we are free we spend on the roof of the houseboat, playing cards and watching the sun set over Lake Nagin.

As the week wears on Mustaq becomes more relaxed with us and we get brief glimpses of the real Srinagar, the one we came to see, not the sanitized Tourist version. He takes me to get my glasses repaired on the back of his moped. My wife and I take a tuk-tuk to the bank, and when we take too long, the driver takes a detour to pick up his two kids from school, who cram into the back next to us. I am waiting for my wife outside the restroom on an unescorted trip to Chakreshwari Temple when I’m surrounded by a group of giggling young girls, who ask if I’m married, and claim me as their boyfriend. They run away with peals of laughter when my wife returns. These glimpses are enough to leave us frustrated when we deal with Hamid, who insists that we are required by law to have a guide at all times, though it is now clear that we aren’t.

When we leave Kashmir on a public bus, we cease to be Tourists. Tourists do not sit on bumpy public buses filled with bags of mail and a few other Kashmiri travelers who blow smoke at the “No Smoking” signs and stare at my wife. Tourists do not eat in cheap roadside restaurants with the locals. Tourists do not arrive at the Jammu bus station as the sun is setting with nowhere to stay and nowhere to go. We are now Backpackers.

The road between Jammu and Kashmir is narrow, and it twists around hairpin turns, dives through interminable black tunnels, and climbs over mountain passes. As we bounce around bends, I look over the edge of the roadway and down, down, down, to the Chenab River which carved the valley we are riding through. I can see the burned-out shell of a bus much like the one we are riding in at the bottom — or is that a rock? My imagination is certain, but my mind is doubtful. The bus stops several times along the road. The winding mountain track is susceptible to landslides, and a recent landslide has blocked a portion of the road; until it is cleared, traffic can only go in one direction at a time. It is eight hours before we arrive in Jammu. We spend six hours there before boarding an overnight bus to Dharamsala, home-in-exile of the Dalai Lama.

Except it isn’t exactly an overnight bus to Dharamsala. It is an overnight bus to Mandi that stops at a junction near Dharamsala. At three in the morning. The bus disgorges us and we stand on the side of the road, wondering what to do next. It is at this point that we wish we were Tourists and not Backpackers. Tourists do not stand on the side of the road in the middle of the night. Backpackers must figure things out for themselves.

There are seven of us: two Irishmen, three Englishmen, and two Americans. We stand in a rough circle and eye each other. There is one small taxi with two drivers, one of the ubiquitous silver Tata sedans, with room for maybe three of us, with gear. A few minutes of conversation reveals that we all had found ourselves on the side of the road in the middle of the night in northern India in much the same way: We’d been talked into staying on a deluxe houseboat that had perhaps once been deluxe but no longer was. We’d been swindled on carpets, cheap trinkets, textiles, saffron, and everything else we’d bought that was supposed to be real but wasn’t. My wife and I had felt like fools for the times we’d been suckered like this, and it was nice to hear that we weren’t alone.

The taxi driver wants 500 rupees each to take us into Dharamsala, which we reject as unreasonable. This is how negotiation here works: One party begins with an unreasonable offer, the other party counters with an equally unreasonable offer at the opposite end of the pricing spectrum. We offer him 50 rupees each, expecting a capitulation, but he doesn’t budge. He has us over a barrel. If he doesn’t give us a ride into town, we’ll have to walk, which at three in the morning isn’t something we want to do.

"Let’s just pay him," someone says, and the driver’s eyes light up.

"I think a bus will be along soon," says one of the Brits, James.

We continue talking about our experiences. Someone lights a cigarette and passes it around. A truck rumbles by, and the driver ignores our attempts to flag him down.

"What should we do?" someone asks.

"I think a bus will be along soon," says James.

"You said that before. Why do you think a bus will come by?"

James shrugs. "I don’t know. I heard that they have buses that run into Dharamsala from here. One will be along soon enough."

"We might be here until morning."

James shrugs again. "I think a bus will be along soon."

The taxi driver decides he’s wasting his time. He starts his car and scolds us in Hindi through his open window as he drives away. The seven of us watch with forlorn resignation as the taxi’s red taillights fade in the distance. I set my pack on the ground and sit on it. No sense standing here if we are just going to be waiting around. The two Irishmen have the same idea, but the opposite reaction. They hoist their packs and head down the road toward Dharamsala, disappearing into the dark after a few moments.

"I think a bus will be along soon."

Out of the darkness two yellow eyes gleam, growing, with a dull roar, into the headlights of a vehicle. A bus! It rolls to a stop in the intersection in front of us and the door opens. James shrugs and smiles, and we all board the bus, paying the eight rupees fare to Dharamsala.

Once we reach Dharamsala, we still aren’t at our final destination. Dharamsala is at the base of an enormous hill, one of the many foothills of the Himalayas, and above us is McCleod Ganj, home-in-exile of His Holiness, the 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet. We find the taxi drivers in Dharamsala to be much more reasonable, and soon are whipping up the steep, curving streets toward McCleod Ganj in a rusty, dented minivan.

Just shy of the crest of the hill, the taxi begins to slow. The driver stomps on the gas and the engine roars, but the van keeps slowing, rolling to a momentary stop before reversing direction and beginning to roll back down the hill. The driver steps on the brakes and kills the engine before turning to us. "The taxi is no more. It will not go."

"This way?" asks James, pointing up the hill. We are no longer surprised when vehicles refuse to work, when the power goes out, when things aren’t what they seemed to be. We have come to expect such things.

"Yes. Not much farther," the cabbie replies, nodding his head.

Of course, once we reach McCleod Ganj, it is still four in the morning, pitch dark, and all of the shops and hotels are locked up tight. Stainless steel doors have been lowered and secured with padlocks. We walk up and down the empty streets, banging on hotel doors occasionally, trying to rouse someone with no success. I am starting to get discouraged when a voice calls out to us.

"Hey, over here. I have a place you can stay!"

We’d been in India long enough to be skeptical. What is this guy doing out wandering around at four in the morning? What is he up to?

Nothing, it turns out. He had heard us making noise, and came out to help. He is a Tibetan refugee and works at the International Buddhist Hostel. He offers us warm, clean beds for a fair price. He knew what it was like to be new in town, and he wanted to give us a hand. It was beautiful gesture. It was moments like these that have brought us to India.

The sun is beginning to rise as I pull the thin white sheet to my chin and drift off to sleep, but I feel exhilarated, as if a great weight had been lifted from my shoulders. We are safe, we have arrived, and we made our own way across the Indian countryside. It has forced us to interact with the population instead of observing them from behind glass. Outside our hotel room, India looms large, waiting for us. We have seen much since we left Srinagar that morning, and much more since we’d arrived in Delhi two weeks earlier, but I know, with certainty, that India still has innumerable surprises waiting for us.

Aaron Richner I am a writer/editor turned web developer. I've served as both Editor-in-chief and Technical Developer of In The Fray Magazine over the past 5 years. I am gainfully employed, writing, editing and developing on the web for a small private college in Duluth, MN. I enjoy both silence and heavy metal, John Milton and Stephen King, sunrise and sunset. Like all of us, I contain multitudes.