- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

Catholic Europe is seeing a Vatican-backed resurgence in exorcisms. The brothers and father of the church, with their good book, believe that demons or the Devil are possessing people. Literally. A few bits from the Washington Post article:

"…people who turn away from the church and embrace New Age therapies, alternative religions or the occult…internet addicts and yoga devotees are also at risk [for possession by the devil]."

Oh no, anything except Christianity will make you evil!

"According to what I could perceive, the devil was present and acting in an obvious way," he said. "How else can you explain how a wife, in the space of a couple of weeks, could come to hate her own husband, a man who is a good person?"

You, sir, have never been married.

"More recent horror stories have also taken their toll. In Germany, memories are still fresh of a 23-year-old Bavarian woman who died of starvation in 1976 after two priests — thinking she was possessed — subjected her to more than 60 exorcisms."

Well, I’m sure she’s in a better place now.

This is the 21st century, right? Didn’t we all get tired long ago of the church’s glory days of burnings at the stake? Didn’t we have these centuries in which things like science, reason, and common sense show us that burning people at the stake was rather silly and cruel? But I know, I know — science, reason, and common sense don’t put a dollar in the collection plate on Sunday.

In another related story:

"The Saudi government is set to execute an illiterate woman for the crime of "witchcraft." She "confessed" to the crime after being beaten by the religious police and then fingerprinting a confession she could not read…Among her accusers was a man who alleged she made him impotent."

I guess Western Christianity and Eastern Islam aren’t so far apart after all. When weak, corrupt, mortal men take the power of God into their hands, the innocent everywhere suffer.

About 10 years ago (perhaps not that long, but it feels like it), I did something really stupid. I gave $25 to the Kerry campaign. It was right after he hooked up with Edwards, when many of us were dewey eyed with our liberal theologies and that nascent hope that W could be vanquished. I gave online. I clicked a box on an email. I was a reporter at the time, so I probably shouldn’t have done it.

More recently (five years ago? Who knows, everything gets cloudy when you move to a foreign country and politicians start campaigning from the crib), I contributed $25 to Barack Obama. A volunteer called me on the phone. She was nice. I respect people who sacrifice their personal time for a cause they believe in. She said uplifting stuff about social justice. White girls are a sucker for that line. She knew it.

*Note to men: If you ever want to get a progressive girl into bed, all you have to do is tell her that you love "social justice and giving sight to the blind." You’ll have to dig up a few articles from The Economist or The New Yorker to back it up. It’s not that hard.

Anyway, because of my past foolishness, I have to delete email campaign contribution requests from Obama every day.

Will I call a friend? No.

Will I join a canvassing party? I live in Korea. And thank god I do because before moving here I was already broke from my meager reporter’s salary and high oil prices.

Hillary doesn’t even try to stalk me. I must’ve been "tagged" early as an Obama supporter. This is what I got Saturday:

"Senator Clinton has decided to use her resources to wage a negative, throw-everything-including-the-kitchen-sink campaign. John McCain has clinched the Republican nomination and is attacking us daily. But I will continue to vigorously defend my record and make the case for change that will improve the lives of all Americans."

When aren’t politicians waging a negative campaign? You all claim to promote changes that will improve the lives of all Americans.

Instead of giving your $25 to put more ads on CBS, why not send it to 826CHI, a literacy program in Chicago (find it online at www.826chi.org). Then take W’s rebate check and save it. Invest it yourself rather than handing it over to the Man to buy more shit that you don’t need. But keep $25 and get a box of Leffe, or a case of cab sauv if that’s your thing. You’re going to need it to get through this political war.

T.P. Mishra shifts his load of 1,000 newspapers from one shoulder to the other. Someone honks at him. He gracefully navigates through the maze of cars, motorcycles, and people competing for space in the streets of Kathmandu, Nepal.

No staffers are paid, and the paper’s monthly budget of 2,500 Nepali rupees (about $40) is contributed by the staff’s editors, many of whom work as teachers. Subscriptions and advertisements are impossible.

Most of the newspaper’s readers are refugees who have lived in camps near Damak, in eastern Nepal, for the last 17 years. They are legally barred from officially holding jobs in Nepal, which means they have little disposable income. In addition, the paper cannot solicit advertisements, since it is technically an illegal publication; Nepalese law does not allow foreign-owned media — like The Bhutan Reporter — to publish their Nepali newspapers and magazines in the country.

“I always feel responsible to the 23 correspondents stationed in camps and other associate editors

stationed in Kathmandu,” said Mishra. “They have been sweating a lot selflessly, therefore the very frequent question I receive is that whether the paper will give continuity to its hard-copy print.”

Sometimes the answer Mishra gives is “no.” The paper, which began printing in 2004, skips publishing at times due to lack of funds. Back in March 2007, The Bhutan Reporter nearly ceased to exist until a story about the newspaper’s plight appeared on Media Helping Media, an online portal for news about freedom of the press in transitional countries. An 11th-hour donation from the World Association of Newspapers saved the newspaper for three months. More recently, a donation from an individual kept the paper afloat through this past February.

Despite the financial hardships, the paper’s reporters and editors remain steadfastly dedicated to

journalism.

During a summer editorial meeting at one of the refugee camps, reporters told Mishra that he must find a way to continue publishing The Bhutan Reporter because it was the one thing they had to look forward to in their lives.

“I go to Damak by bicycle to bring [the] newspaper to camps,” said Puspa Adhikari, one of the paper’s special correspondents, referring to the town about an hour’s bicycle ride from the Beldangi refugee camps. “I face lots of difficulties; I have ambition to become an international journalist.”

Adhikari’s dream is the same dream as many of the paper’s other reporters. But a lack of educational resources and opportunities may keep their dreams from becoming reality. Most of The Bhutan Reporter’s staff do not have formal journalism training, and indeed, this is sometimes reflected in the newspaper’s stories; they do not always name sources or attribute information. Readers, too, have suggestions for improving the newspaper.

“If this paper could add more reporters, they could give more fresh news from on the spot. It is lacking this,” said Kapil Muni Dahal, a 10th-grade Nepali language teacher at a school inside one of the seven refugee camps.

Despite this lack of fresh news, Dahal said, “I share the paper with other people whenever I get it. I read it among the group and translate it into Nepali, and the people listen and interact.”

It’s that commitment to readers like Dahal and his friends that keeps Mishra and the rest of The Bhutan Reporter staff working on the paper month after month. Their dream is to transform the newspaper into a bimonthly publication, and more.

“We have been working, keeping the aim that one day we will reach establishing this paper as the leading paper of Bhutan,” said Mishra.

[Click here to enter the visual essay.]

Vanity Fair‘s new issue features a big, glossy spread about famous funny women. A year ago this same magazine ran Christopher Hitchens’ piece about why chicks aren’t funny, in response to which women with nothing better to do stood up and proclaimed that they, too, laugh at fart jokes (I don’t) or proved Hitchens’ point by acting, you know, humorless, and even suggesting censorship.

Now the funny females are getting their due in what is essentially another celebrity rag. Except, I never cared in the first place. So a bloated Brit had an opinion — why should I care? The last line of the article, provided by Tina Fey: "[She] says that there are people who continue to insist that women are not funny. ‘You still hear it,’ she says. ‘It’s just a lot easier to ignore.’"

Toward the end of every year, it seems warnings resume anew about an inevitable fare increase for subway riders.

The discussion between the transit authority, politicians, union groups, and advocacy organizations feels almost scripted.

MTA: Remember that $32 billion we borrowed over the last 25 years? Well, the bill’s coming due. Time to raise fares.

Governor Spitzer: On behalf of all of the low-income workers in New York City, this is an injustice! There must be something we can do. As you know, my proposed legislation to give driver’s licenses to illegal immigrants failed, so I am jumping on the "no fare increase" bandwagon to divert all of that bad publicity.

Straphangers Campaign: Can’t the MTA wait at least until March 2008 to raise fares? That’s when they submit their five-year, multi-billion dollar capital rebuilding plan for approval. Seems kind of short-sighted to ask for an increase now. Anyone?

Mayor Bloomberg: No comment.

MTA: Wait just a minute! What do we have here? Looks like we found $220 million laying around in this old shoebox marked "Extra money." Guess we don’t need to increase fares in 2008 after all.

Governor Spitzer: Whew! But come to think of it, Albany is running at a $4.3 billion defecit. We should at least raise the unlimited Metrocard fares. Four percent seems like just the right amount not to ruffle any feathers.

Straphangers Campaign: Well that about does it. See you this time next year.

Type “March” and “month” into Google, and you’ll discover that the third month of the year wears many hats. March is National Kidney Month, Women’s History Month, National Nutrition Month, and Red Cross Month, just to name a few. In this issue of InTheFray, we look at what unites March’s many causes: the body — and women’s bodies in particular.

We begin in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where ITF contributors Anna Sussman and Jonathan Jones make a harrowing discovery: Rape in the West African nation has become the norm, a reality that both locals and the international community have come to accept. In an accompanying podcast, Sussman and Jones reveal just how excruciating this trend is when they speak with a rape victim and a Congolese doctor.

On the other side of the continent, women aren’t faring much better. As A Walk to Beautiful director Mary Olive Smith explains during her interview with fellow filmmaker and ITF Director Andrew Blackwell, a rare childbirth-induced injury has sentenced many Ethiopian women to shame and isolation. But as Smith’s documentary reveals, some women are rallying for a cure.

In Ghana, meanwhile, Julia Hellman discovers a new sense of community — and self — while tending to the body of a friend who died at an underresourced regional hospital. And in South Asia, ITF Visual Editor Laura Elizabeth Pohl documents the implausible perseverance of a Bhutanese paper that delivers news to refugees living in camps in eastern Nepal.

Back in the United States, Ashley Barney looks at a lighter side of corporeal (and sometimes romantic) existence. In What ever happened to college dating? Barney explores how complicated dating has become for a generation who speak of “hooking up” and “friends with benefits” instead of “going steady.” Taking this look at language and self a step further, poet Cheryl Snell and artist Janet Snell collaborate to provide annotated and illustrated looks at relationships with doctors, lovers, gender, and the truth. Be sure to check out the accompanying podcasts of Cheryl reading her work.

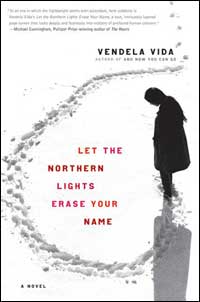

Rounding out this month’s stories, ITF Books Editor Amy Brozio-Andrews tackles the relationship between names and identities in Rewriting History , her review of Vendela Vida’s Let the Northern Lights Erase Your Name.

Coming next month: a special issue devoted to religion and politics.

Thanks for reading! We hope you enjoy this issue as much as we have enjoyed putting it together.

Laura Nathan

Editor

Buffalo, New York

The word “dating” is not in the vocabulary of many college students. It seems like a relic from the college days of their baby boomer parents, joining other words on the verge of extinction, like “wooing” and “going steady.”

No longer is the man expected to pick the woman up from her house and take her to a “nice restaurant” for dinner. No longer is the man expected to pay for the date. No longer is the man even expected to be the one who initiates the date. These unspoken changes have made many college students question whether the traditional notion of dating has become out-of-date.

A random sampling of college students found that dating isn’t dead, it’s just very casual. “Because dating today is a lot more informal, where dinner and a movie used to be the norm, nowadays dinner in the cafeteria or a trip to the library could work,” says 19-year-old Howard University sophomore Marie Smith. The Virginia native pointed out that a couple mutually agreeing to meet one another at a party can be considered a date.

Dating is further complicated by ambiguous language: just talking, hooking up, friends with benefits, and open relationships. These words are all used to avoid the dreaded concept of commitment, their “kryptonite.” These semi-relationships alleviate the pressure of a real relationship by allowing both parties to leave their options open.

The ever unclear “hooking up” seems to be the most widespread phrase favored by college students. A 2001 study of college women sponsored by the Independent Women’s Forum, an advocacy group, found that “hooking up” was defined as when “a girl and a guy get together for a physical encounter and don’t necessarily expect anything further,” with the definition of a physical encounter ranging anywhere from kissing to having sex. However, the study also noted that “hooking up” can be used to describe a third party who introduces two people, or simply going out with someone — not necessarily in the romantic sense.

The average college student was raised to believe in equality between the sexes, which has resulted in the blurring of gender roles. While the burden of asking and paying for a date is no longer expected of the guy, the Women’s Forum report suggested that there are still very few girls who would ask a guy out on a date.

Blair Alexander, an 18-year-old Morehouse College freshman from Maryland, thinks that as a guy, he should pay for the date even if the girl initiated it. “It’s about chivalry and it’s just the polite thing to do. I believe this because this is what I was taught by my father,” he said.

Marie Smith agrees. “I expect to be approached, which is a dangerous and unfruitful game, but I’m kind of old-fashioned,” she said.

The shift of the gender roles also leaves both guys and girls unsure of who should make the first move — which often results in no one making a move at all. New York University (NYU) senior Karim Hamadi, who is from Maryland, says: “I sometimes will make that first move if I am interested, but I am the kind of guy that genuinely appreciates and loves when women make the first move.”

Not all girls share in the hesitancy of approaching someone who interests them. NYU sophomore Caty Wagner, of Connecticut, has no hesitation about asking a guy out. “I am a big believer in not letting life pass you by, and if I see someone I think can be ‘the one,’ I’d really regret not going for it.”

To approach or not to approach? Is it a relationship or a hookup? Dating may have become more casual in recent years, but it is no less complicated.

![]()

Producer and director Mary Olive Smith’s new documentary, A Walk to Beautiful, follows five Ethiopian women who struggle with an isolating medical condition and who set out on a search for treatment.

A lack of basic health care during pregnancy and delivery in parts of Africa leaves some women with debilitating physical injuries after childbirth. Mary Olive Smith’s new documentary A Walk to Beautiful examines their hardships — and their quest for a cure.

Smith recently spoke with filmmaker and ITF Director Andrew Blackwell about how the documentary came about, the women in the film, and the political implications of her decision to let the camera linger on Ethiopia’s incredible landscapes.

Interviewer: Andrew Blackwell

Interviewee: Mary Olive Smith

What is the story of A Walk to Beautiful?

It’s about five women in Ethiopia who have suffered from serious childbirth injuries, and live in isolation and loneliness as a result. The film follows their journeys to a special hospital in Addis Ababa, where they hope to find a cure.

The real story is one of women who have been shunned by society and who are trying to regain their dignity and their lives, and become whole people again. It’s a human story, a story of personal transformation, not a medical story. The medical problem is the struggle, and we explain that, but the journey is a personal one.

What is the medical problem they are struggling with?

It’s called fistula, and it’s really a hidden problem. Very few people know it exists. The [United Nations] U.N. campaign to deal with it only began five years ago, although the problem has been around as long as humankind.

It’s an injury that is caused by prolonged, unrelieved, obstructed labor. Even in the [United States], obstructed labor occurs in 5 percent of all deliveries, but here the problem is overcome by Caesarean delivery. But in the poorest countries of the world, where there are not enough doctors or hospitals, these women basically need a Caesarean section, but don’t receive it. And there are higher rates of obstructed delivery as well, due to early marriage and pregnancy as well as malnutrition. So these women end up in obstructed labor for days on end, and they either die or they end up with severe injuries. They can be crippled, or get fistula, which causes incontinence.

The reason they’re incontinent is that, after days and days of obstructed labor, they end up with a hole between the vagina and the bladder. And there’s no way to get better without surgery. The bladder doesn’t hold the urine, so it’s constantly coming out. They smell, they are too poor even to have diapers or underwear, and it doesn’t matter how much they wash.

They think they are cursed. They have no idea that it’s a physical injury. Many of them go to hospitals, and the hospitals don’t know what to do with them. And their communities shun them. A lot of the doctors call them modern-day lepers. They are no longer part of society. They just disappear. The response depends on the family, but as a rule, they no longer can hang out at the market or at the well. Some of them are so afraid and ashamed that they go to wash their clothes at night, and their families just leave food out for them.

There are exceptions, in which the family maintains strong support, and it varies from country to country. But in rural Ethiopia, the stigma is very strong. It’s not that they blame the person; they just don’t want to be around them. And the women are too ashamed to go out as well. For the most part, they are rejected by their community. In the case of Ayehu, a young woman who we followed for the film, her siblings were really cruel. Her mother was her only defender. When we met Ayehu, we found her living in a makeshift lean-to that she had put together with sticks against the outside of the back wall of her mother’s house. She would crawl in there and sleep on the floor. Even during the day, she would just sit in there. She would never come in to the house; she wasn’t allowed.

Why is the community and family response so harsh?

The families don’t abandon them at first. I met family after family who took them to the hospital. They’ll sell their goats to raise money to try to get them help. But often they don’t encounter anyone who knows how to deal with fistula, and if they haven’t heard about the Addis Ababa Fistula Hospital, or if it seems too far away, then there’s nothing they can do.

It’s true, women in these areas are second-class citizens: They do most of the work, they don’t have property rights, and they are definitely subordinate. But if a man had the same condition, I think he might not be treated much differently. The smell is very bad; there’s no way to control the flow of urine, and people just don’t want to be around the person. I don’t think you can really point your finger at the culture. The situation comes more from poverty, which creates both the conditions that lead to the injury in the first place, and the circumstances that keep it from being treated.

How did you come to make a film about fistula?

I work for a company called Engel Entertainment, a documentary production house based in [New York City]. I’ve been working there for 12 years. The idea came from an op-ed in the New York Times by Nicholas Kristof in May, 2003, called “Alone and Ashamed,” in which he wrote about women at the hospital suffering from fistula. It was a really moving piece. A friend of Steve Engel, who is the president of our company, brought the idea to him, and Steve took it up as a documentary project. He asked me if I would be interested in directing the film, as I have a longstanding interest in human rights in general, and in Africa in particular. We had always done television in the past, for [stations] like Discovery, PBS, and so on. But this time we wanted to do it as an independent feature documentary.

And so the film follows these women to the hospital?

The first half of the film is that journey to the hospital. Ayehu knew about the hospital before we met her, but she was too afraid to go. Again, it’s a long way away, and they’re unsure if it’s going to be costly, and they’re afraid of going to the city. Going to Addis Ababa can seem like going to the moon for them. But she was convinced to go by another woman who had had the treatment. And so we followed her, as well as two other women, who made the journey separately. The trip means walking for hours and hours, and then a 16-hour bus ride. The treatment itself is free, and they can even get money for the trip home, if they can just get themselves to the hospital.

The middle of the film is at the hospital. When Ayehu gets to the hospital and is given a bed, you see her smile for the first time, as she realizes that she’s not the only one with this problem. … she is amazed that there are 120 women also there who have the same problem as her. And it’s a really open, neat place — very lively — and they can socialize. There’s a real transformation in them as people, even before they get the surgery.

The twist in the film is Wubete, another woman who we met in the hospital. At age eight, she was married off against her will. She was beaten by her husband, became pregnant by him, and had this fistula as a result of the delivery. She’s so beautiful, and her family doesn’t want her. But in her case, the treatment was more complicated, and it was unclear whether or not she would be cured, and we followed her as she dealt with that. In addition to her story, the latter part of the film shows the other women returning to their homes, and becoming part of their community again.

Ethiopia has a lot of stereotypes associated with it, going back at least to the famines of the 1980s, which received so much media coverage. But your film really seems to portray it in a different way.

Some films really show the squalor and hopelessness in African countries, so I really wanted to show how beautiful Ethiopia is. I get tired of the portrayal of Africa as a hell on earth. There is so much beauty and hope there. And there was such a contrast between Ayehu’s situation and the beautiful landscapes. So Ayehu’s leaving her shack and going on this journey through this beautiful environment sort of represents the hope in her poor conditions. Our cinematographer and editor really brought that out.

Although I hadn’t been to Ethiopia before, I wasn’t surprised at how beautiful it was, as I had been to other parts of Africa. And I wanted to bring out the beauty of the country, in a way to represent the dignity of the people there. The women in the film have so much dignity as they go through this process. Ethiopians in general have responded really well to the film. Although it shows a difficult situation in their country, they see the dignity of the people we show, and realize that it’s a personal story, not an indictment of their entire country.

Also, after the devastation of what the film shows — people often describe the film as “devastating” — there’s excitement that comes with realizing that these women can be helped. The Addis Ababa Fistula Hospital is becoming better known, and more women therefore have the possibility of making the journey there. And if you can imagine being a leper of sorts, and then after being treated, being allowed to rejoin the community again, there’s real joy there.

For those who wish to help women suffering from fistula receive restorative surgery and care, visit www.fistulafoundation.org.

Clarissa Iverton’s mother once told her she was named not after Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, but Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa: “I named you after this Clarissa, with the hope that you’d rewrite history.” When that opportunity comes years later, it’s up to Clarissa to decide whether or not to take it, in this third book by Vendela Vida.

At 28 years old, Clarissa earns her living editing subtitles, cleaning up poor translations of foreign language films, and fixing other people’s words so that their meaning is clear. Ironically

though, nothing can fix the discovery of another man’s name where she expects to see her father’s listed on her birth certificate. Even more stunning, Clarissa’s fiancé admits that even he and his mother had known the truth for years. Never having fully come to terms with the disappearance of her mother, Olivia, 14 years earlier, this fresh vanishing of a parent sends Clarissa into an emotional and existential tailspin.

Adrift in grief and betrayal, Clarissa takes off for Finnish Lapland in search of her real father, the Sami man whose name is on her birth certificate. Clarissa’s search within the Sami community, despite her being unable to speak the language, is surprisingly fruitful, but not in the way she anticipates. In a complete reversal, the level of communication between Clarissa and the people she meets in Lapland is light years beyond the depth and breadth of the communication between the people with whom she shares a language, a home — even blood — prompting her to reexamine all she has previously believed about family, community, and identity.

Vendela Vida’s spare and concise prose is more like a series of vignettes than a long, detailed narrative. Yet it makes real to the reader the desolation and isolation of Finnish Lapland’s geography, of the insular Sami people, and of Clarissa’s feelings of aloneness. In spending two weeks among the Sami, Clarissa isn’t known as Olivia and Richard’s daughter, Jeremy’s sister, Pankaj’s fiancé; she’s half a world away from home and stripped of the identity pressed upon her by those around her.

It’s only through reconciling what she’s learned about her family history with what she articulates about her own personal history that she can even consider rewriting anything, balancing what her family — her mother in particular — may owe her and what she owes them. Only by fully realizing the truth of who she is and where she is from, can Clarissa transcend a legacy of secrets, betrayal, and grief.

The women next to me are crying. Silently, to themselves, but unabashedly. As the men in the truck bed look over the terrain, their faces are abnormally blank and sullen. My face is squished against the window in the crowded back seat, and I notice the ubiquitous red dust (a staple of West Africa) flying off of the road as we drive. Like it does every day, today it coats the banana leaves, cocoa trees, and assorted green bushes that cover Ghana. People are still walking along the road with baskets on their heads, smiling at everyone they meet and maneuvering around goats that flood the streets and bleat loudly.

But unlike these people who move to the normal, almost ineluctable West African rhythm, today does not feel like a normal day for me. In shock, I can’t believe that I’m driving along a dusty road in Ghana, with the wind whipping in through open windows, and my dead friend Raymond wrapped in a blue bed sheet on the truck bed behind me.

I’d only met Raymond once before that day. About a week into my six-week volunteer stint in Ghana, I began working in the Accidents and Emergencies Ward in the Volta Regional Hospital — a different experience from being in American emergency departments, because the hospital had no ambulances, defibrillators, or electrocardiograms (EKGs). The primary emergencies that they managed were broken bones, sutures, or diabetic emergencies requiring IV fluids.

Because I didn’t speak the native language, Ewe, I felt like I was being ignored in the hospital ward. After about a week-and-a-half of this, I wandered over to the General Male Ward where I knew some other volunteers were working. I spotted Katie, with her short, curly hair escaping from the pigtail braids she had tried to wrestle it into, and the top half of her head bleached blonde from the sun. She had taken out her large, silver nose ring, but I could still see the two bluebird tattoos peek out from behind the straps of her tank top. Amy, a quiet, blonde volunteer, was hunched over a shopping bag on a windowsill. As I entered the ward, she looked up and kindly smiled before pulling a package of adult diapers out of the bag.

Katie called me over to where she was, sitting at the head of a bed with the remnants of a Fanchoco ice-cream bar coating her hands. “This is Raymond,” she explained, gesturing to a rail-thin figure lying on the bed next to her, “and he is here from Togo.”

Immediately I felt excited because I could practice my French with him. Katie patted his arm and told me that he had “eaten some bad beans” that made his stomach hurt, and that medicines from an herbalist had only made him more sick. The family took him to one hospital, but the hospital’s operating room “couldn’t help him,” and so they sent him to the Regional Hospital. In the meantime, the wound from his surgery dehisced so that the intestines basically spilled out through the hole. They were held in only by the diapers that he wore in the hospital.

Without much muscle mass, Raymond was basically a skeleton wrapped in a sheet of his own skin. I stared at his huge feet attached to twig-like legs. His knees were by far the largest part of his legs, bulging out like two baseballs between two muscle-less sticks. When Katie told Raymond my name, he looked at me with velvety brown eyes. His eyes reflected a thousand pains, but they were also the strong eyes of a 17-year-old boy. Reclining amidst a sea of sheets, he held out a limp hand with long fingers for me to shake.

We all chatted for a while, learning about each other’s lives. Raymond told us how his sister sold green beans in the marketplace in their hometown, Aflao. He eventually asked Katie when she was returning to the United States. I translated for Katie while she pointed to a date in her planner. August 4. “That is when I go home,” she said, being careful to speak without contractions like the Ghanaians did.

Raymond turned his wide eyes to me and stated matter-of-factly, “I will go with her then. Tell her I go to America, too.”

As I relayed the message to Katie, I shifted my feet beneath me and glanced at Amy, who was still sitting on the windowsill next to Raymond. Katie looked at me with thoughtful, slightly sad brown eyes, and then playfully patted Raymond’s hand. “I’ll try,” she said grinning at him, “but you have to get some more muscle before then!”

I decided to translate “try” as essayer. Once Raymond understood me, his eyes bulged with alarm, and his whole body writhed as he shouted, “No! Not try! Will! Will! You will bring me with you!”

Katie stared pensively at Raymond’s smooth hands as he assured her that he would be big and strong in three weeks. Nodding along, she untwined her fingers from his and turned his palm over delicately. Sliding her hand over his, she wrapped her fingers around his wrist. “OK, Raymond,” she said, noticing how her fingers made a complete circle around his arm, with room to spare on all sides, “I will. But remember, big and strong.”

Raymond nodded at her and found a pencil from a table next to his bed. With shaky but deliberate movements, he leaned over Katie and wrote his name, RAYMOND, in her planner underneath August 4. “Now it is a plan,” he explained, pulling up a sheet so that it covered his diaper. “I am going to America.”

About a week later we went to the hospital again and brought more volunteers. I was laughing as Katie stomped and banged on her Jimbe drum, imitating our drum teacher, Joseph, and his testosterone-filled teaching style. The drum had a resounding, hollow, but somehow pure sound that broke up the relative silence in the ward. As we walked in, one of the nurses (in Ghana, nurses are “Sisters”) smiled sheepishly from behind the administrative desk. Her hand stopped its casual lilt on the page, and hesitated for just a moment. “You are here to see Raymond?” she asked out of complete stillness.

“Yes,” we answered, blundering into the room and talking amongst ourselves.

“Ah.” Pause. “We lost Raymond this morning.”

I turned my head to the Sister, whose hand was still frozen on the page, and Katie stopped drumming. We all stood still. The Sister’s words hung in the air like reverberations from a musical performance, and in their silence they were almost as loud as the sounds from the Jimbe drum. The sudden change from loud to quiet echoed the unexpected news we had just received, and I couldn’t believe what had happened.

It was a particularly warm day when we got Raymond’s body from the morgue. It’d been about a week-and-a-half since he died, and his body had been kept in refrigeration. When they brought Raymond out, I was shocked by how peaceful he looked. He was so still that it was as if he had eternally extended the pause between inhaling and exhaling so that there was a breath trapped inside of him. His mother and Katie couldn’t stand to see him, and so I cleaned his body with two of his aunts and Becca, a nursing student volunteer with a sunny disposition and a go-getter attitude.

I kept wondering why I was cleaning his body in the first place. Holding his lifeless left hand, I realized that I had only met this boy once before, and that I hardly knew him at all. I wasn’t sure why I even cared about what happened to him. But as I wiped his elbow with a rag, I thought about how happy it had made him that we came to visit him. I realized that the whole reason I came to Ghana was to connect with new people and to learn from their life experiences. I’d certainly met many people when I observed a physician, blood lab technicians, or a traditional bone healer. By spending time with these people I was able to learn a lot about their life stories.

But I just sort of stumbled upon Raymond and his story, and it still impacted my life. I realized that these informal relations are clearly important ways to make a connection with other people. Even more significantly, I understood that by making Raymond even a little bit happier, I had affected his life as well. Gazing into his slightly sunken, matted eyeballs, I realized that I was giving back to him for what he had taught me. It became clear that these sorts of informal connections, with Raymond and with other West Africans, were not only important, but actually some of the most significant ways through which I gave back to Ghana.

Back with Raymond, I still felt confused as I moved the rag between his bony fingers, but I also felt in awe of our own connection and what it meant.

It is almost afternoon by the time we leave the morgue and arrive at Raymond’s family’s house in Aflao with his body. We plow quickly through the unpaved streets, which are more like glorified paths, and dodge chickens and avoid hitting huts on either side by six inches.

When we pull into a clearing, people are milling about between the noises of chickens and goats. Jumping out, the men seem to know what to do and start speaking in Ewe. Against the backdrop of a dialect that sounds like a rushing brook, I feel completely confused.

Raymond’s mother grins at me with the type of smile that turns complete strangers into instant friends. Other volunteers had mentioned that she had been extremely distraught over her son’s death for about a week, but it looks like she has finally calmed down and is able to interact with other people. She waves me over to a group of people who are the rest of Raymond’s family. I almost cry when his younger sister looks at me with her huge eyes and holds out a hand that also has long fingers like Raymond’s.

The men hoist Raymond’s body onto their shoulders and carry him to a sandy area. I guess this is a cemetery, though the only grave markers are Coke cans and plastic wrappers. One of the family members starts digging a large hole to my right. I am still confused about what I should be doing, and so I stay back with Becca, kicking the sand with my flip-flop. I watch Raymond’s father lower his son into the hole, and I watch the different layers of sand cascade around Raymond. “No grave marking,” everyone explains to me, but “maybe the family will plant a tree later.” I take a last look at the grave, now a wet patch of sand, and go back to the compound, stepping on a dusty Fanchoco wrapper on the way.

Back in the clearing, in the huts, I meet members of Raymond’s extended family. I shake about 20 hands, and I see so many faces that are creased with age and worry, but they crinkle even more with warm smiles for me. I feel embarrassed, like I haven’t done anything to deserve this kind of unstinting love from strangers. Raymond’s mother gives me a huge hug as she sobs silently, and Raymond’s sister kisses me on the cheek as she walks back elegantly to her father, like a dignified queen, even though she is crying.

Continuing this generosity, someone hands me a coconut he has just chopped open and his eyes simply say, “Thank you.” As I drink the milk, another relative throws more and more coconuts back into the pick up truck. After convincing them that I cannot take coconuts with me, I slide back into the truck and wave goodbye.