- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

Cokie Roberts does NOT speak for me.

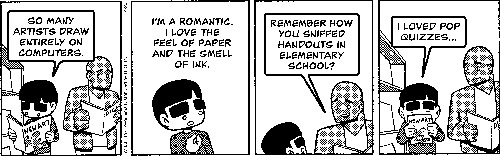

The Bible is America’s favorite book, followed by The Da Vinci Code and Angels and Demons. My head hurts. I suppose it could be worse. America’s favorite book could be Mein Kampf or something written by Danielle Steel.

First Lori Gottlieb got a book deal to expand on her article advising women to settle for whichever men they can. Now that book will be turned into a movie. I can actually understand this, too. The more outrageous your idea is, the more attention it gets. The more attention, the more views and hits. Then the more ad revenue, the more profit. This is a cash cow — of course they’re going to milk it. If any man or woman will take advice on something like whom they will vow to spend their lives with and create children with from a spoiled Beverly Hills dabbler, that’s their problem. Adults make even worse decisions than that everyday. But I wonder how Gottlieb, or anyone, would feel after finding out after a time that they had been the settled for — the person his or her spouse looks at and thinks, "Well, she’s all right enough, I guess."

Single people are being blamed for the bad environment. Because they cohabitate separately, they use more electricity than if they were in a single household. That’s the new theory, anyway. It wouldn’t have anything to do with the fact that families now live in McMansions full of electrical appliances. Or that most households have more than one TV, including one per child’s room. Not to mention more than one computer, cell phones and iPods charging, outdoor lights lining the walkway, etc. It also wouldn’t have to do with the fact that there are now SIX BILLION PEOPLE in the world!

Six teenage girls and two teenage boys in Florida will be charged as adults after videotaping themselves beating a 16-year-old girl unconscious for insulting them online. Oh honey, you should see what they do to you in prison.

Cyber bullying is one thing, a whole other post, a separate crime on its own. But this was a single girl writing things online. As the police chief said, writing childish insults on MySpace does not justify being beaten unconscious, beaten again when you come to, permanently losing hearing and sight on one side, and having it all filmed for the entertainment of others.

I can actually understand the mothers who defend their criminal offspring. Think about it. They’re not defending their children — they’re defending themselves as parents. They’ve created the monster, much like Bush created the war; now they can’t admit that they’ve failed.

Consider the first thing the mother said in the Today Show interview, clarifying that she does have custody of her daughter. She wanted to clear up her own reputation first: she is not an unfit mother who has lost custody or would give up her daughter. She wants you to know that she alone raised one of these girls.

As for their kids, these parents cling to tiny details about the attack because they need to somehow justify having raised a pack animal, an adult-in-training, who plans, carries out, and participates in these uncivilized, illegal acts. That involves cruelty, apathy, a lack of self-control, and ignoring right from wrong. At the very least, you’ve raised a coward who would stand by and watch a girl get beaten unconscious.

Every parent involved will have an excuse: "My child didn’t hit. My child warned her not to come in the house. My child was insulted online. My son didn’t know what was happening behind the door he was guarding." Because to admit that your child did this, you admit that you failed as a parent. They can’t admit that to the world; more importantly, they can’t admit it to themselves. And if the parents cannot own up to their own mistakes, their kids never will.

During the Constitutional Convention of 1787, Charles Pinckney of South Carolina advocated the addition of the following phrase: “but no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the authority of the U. States,” prompting a brief but intense examination of the role of faith in politics from the earliest days of American history. Those against the phrase believed that Enlightenment liberalism negated the need for such a test. Advocates of the phrase believed the requirement of a federal ban on religious tests would preserve the tests already practiced by the states at the time.

Fresh from their own contentious state conventions, the delegates sought to avoid the subject of religion in the Constitution. They trusted that the practice of religious freedom in general would prevent any one sect from dominating all others and casting undue influence over politics.

The honeymoon of religion-free politics was short-lived, however. Just three years later, a de facto religious test dominated the 1800 presidential election. Thomas Jefferson believed firmly in a private faith, between a man and his God. John Adams advocated that faith belonged in the public sphere, with the ultimate goal of preserving morality. Adams explained his loss of the presidency by reasoning that Jefferson’s camp framed the election in terms of religious liberty or religious orthodoxy; given those options, Adams, years later, didn’t fault the American people for choosing religious freedom over the risk of the establishment of a national faith.

Now, more than 200 years later, much has been made of religion in this current election cycle. Despite the constitutional separation of church and state, the two have in fact had a long, convoluted, intertwined history, as explored by Frank Lambert in his new book, Religion in American Politics: A Short History. While no official faith-based litmus test has ever been established for those running for elected office, Lambert, a history professor at Purdue University, posits that the influence of religion is, and has been, both foreground and background in American politics.

In America’s early days, the Founding Fathers put their trust in the idea that religious pluralism would defend against any one sect or faith becoming too powerful. This was despite the fact that vying factions argued either that it was folly for the young nation not to acknowledge the work of providence in its creation, or, in order to avoid widespread religious conflict and oppression, that it was critical that no religion be nationally established. The resulting lack of federal — and later state — support mobilized religious groups to work within the political system to achieve their goals.

The role of religion in American life, and politics in particular, has resurfaced numerous times throughout American history. In his book, Lambert examines the roots, evolution, and developments of this relationship through the days of westward expansion, the rise of industrialism, the Gilded Age, post World War II, the rise of the conservative-leaning Moral Majority of the 1980s, and the dynamic between the Religious Right and the Religious Left as we approach the 2008 election.

Time and time again, the issue of faith has shaped and influenced American history. In the early 1800s, congressional approval of Sunday mail delivery was seen as a choice between the obligation of a Christian nation to keep the Sabbath holy and the federal government’s obligation to provide a national economy with the infrastructure necessary for growth. The Scopes trial of 1925 crystallized the conflict between science and religion, as John Scopes stood trial for violating the law that prohibited the teaching of Darwinism in public schools. Meanwhile, religious groups of the day resisted the growing influence of scientific thought on the basic tenets of faith — for example, the view of the Bible as a historical document instead of God’s literal word, or the use of technology in the form of radio with the growing influence of orators who celebrated their faith and motivated their followers.

In the 1960 election cycle, voters rejected an unofficial religious test in the Nixon/Kennedy race, merely requiring that their candidates reflect general Protestant heritage and values — a civil religion — allowing for the election of the Catholic Kennedy. Twenty years later, born-again Christian President Jimmy Carter, seen as a man of character and values, and who was elected in the wake of the turbulent Nixon administration, was repudiated by evangelical supporters after he failed to align his administration with their goals. This was another watershed moment at the crossroads of religion and politics that contributed to the dominance of Moral Majority in the American political landscape of the 1980s. It also contributed later to the election of George W. Bush, a candidate who, in effect, responded affirmatively to an unspoken religious test, an assurance to conservative Christians and evangelicals that his goals and theirs were aligned.

Lambert examines the centuries-long evolution of the relationship between politics and religion, and its ebb and flow in response to social, cultural, and economic concerns. His work shows that the arguments made by the Founding Fathers as a basis for their foregoing a religious litmus test, that religious conflict would jeopardize the “more perfect Union” that they’d worked so hard to attain, show an eerie presentiment. As the political right and left ratchet up their rhetoric in the run up to the 2008 presidential election, there is a divisive religious undercurrent that remains.

In 2007, the signs were clear that the unofficial religious test still existed as mainstream media reported on voters’ concern about Mitt Romney’s Mormon faith. He stated in a December 2007 speech at the George H.W. Bush Presidential Library that “Our Constitution was made for a moral and religious people.” And in early 2008, Barack Obama, who had been quoted in 2006 as saying that it is a “mistake when we fail to acknowledge the power of faith in the lives of the American people,” was forced to defend his membership at Trinity United Church after the pastor of the church was reported to have made racially divisive statements.

The eight major eras Lambert chooses to examine more closely in his book reflect times of great change and opportunity in America — economically, politically, and socially — which is expressed in both politics and religion. The book weakens slightly in the middle, but is buttressed by a very strong beginning and ending.

Perhaps Lambert’s most successful achievement with his book is the correction of the perception that this phenomenon is anything new, or that it will go away any time soon. The book is light on suggestions for a resolution; but Lambert’s framing of his discussions so firmly in American history seems to suggest that only by reigning in all sides, in keeping with the Founding Fathers’ original intentions, can the tide of increasing vitriol be stemmed.

Those who personally witnessed Barack Obama’s Philadelphia speech on race were riveted by what many consider to be an address of historic importance. Given the sobering nature of the moment, ovations from the Constitution Center audience were few and far between. However, at least one remark by Obama drew applause: It was his recalling of the well-worn saying that the “most segregated hour in American life occurs on Sunday morning.”

This truism pushes out beyond the pews and continues to be played out long after Obama’s speech ended. Whether critical or laudatory of Obama’s words, the predominantly white editorial voices in the mainstream press largely agreed that Reverend Jeremiah Wright’s comments were scandalous, racist, and far afield of sober public opinion.

On the other hand, many of my fellow black folk and people of color understand why Obama had to distance himself from Wright’s remarks, but they don’t necessarily disagree with those remarks themselves. (In the same way, many people of color understand that Michelle Obama’s comments about being proud of the United States for the first time in her life were politically clumsy, but not the least bit unreasonable.) They might not openly discuss this around an integrated office watercooler, but such expressions of sympathy with Wright’s point of view can be found in side conversations at the office, inside people’s homes, in Internet chat rooms, and in the barber shops and hair salons that Obama references in his speech. And despite Obama’s claims to the contrary, this conversation is happening across generational lines, among the embittered and the upbeat alike.

Even the comments by Wright considered to be the most incendiary — the idea that the violence directed against Americans on September 11, 2001, was karmic comeuppance for America’s legacy of imperialism and violence abroad — resonate widely in the black community and in houses of faith. Just like Obama condemned Wright’s remarks, Elijah Muhammad sanctioned Nation of Islam Minister Malcolm X because he made the “chickens coming home to roost” comments about the assassination of John F. Kennedy, comments that also tread on what is considered to be sacred political ground.

Reverend Wright is hardly a fringe figure on the American religious scene. The church where he pastored until recently, the Trinity United Church of Christ, has over 10,000 members. The reason Wright’s views figure so prominently at Trinity and countless other black churches is because the black church, going back to the time of slavery, has always been the place where black folks have indulged in conversations considered subversive.

Furthermore, Reverend Wright is not unlike countless other kente cloth–clad ministers throughout the country with sizable followings who are critical of everything from right-wing politics to hip-hop music. These messages are inseparable from a promotion of self-determination, self-help, and self-love, which some might dismiss as Black Nationalism.

In the same way the black church incubated so much political activity during the civil rights movement, Trinity United Church of Christ was compelling enough to Barack Obama that he was a member for 20 years and gave tens of thousands of dollars to it. For politically conscious black folk — particularly members of the middle class who are acutely aware of glass ceilings — their church can provide a space where racial justice is viewed in spiritual terms, a sanctuary where hard truths can be spoken and where righteous political action can be inspired. The Bible — a text that champions struggles against state power, oppression, and injustice — is the perfect trumpet of this message.

While Obama bravely waded deeply into the waters of race, he profoundly understated how much Reverend Wright speaks for a great deal of black people across the country, including Obama himself. That is something from which neither America nor candidate Obama can hide.

Mark Winston Griffith is senior fellow for economic justice at the Drum Major Institute for Public Policy.