After journalist Mark Jacobson comes into possession of a lampshade — purportedly made out of human skin at a Nazi concentration camp and pilfered from an abandoned house in post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans — he takes a voyage into the unfathomable.

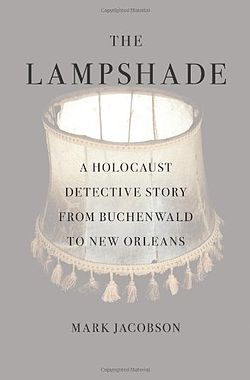

Jacobson describes this journey in his new book, The Lampshade: A Holocaust Detective Story from Buchenwald to New Orleans, initially focusing on the roundabout way he got ahold of the grisly artifact. In the chaotic wake of Katrina, Dave Dominici — a “gap-toothed” junkie and convicted cemetery bandit — was rummaging through a pile of left-behind belongings in a home in the Bywater neighborhood of New Orleans when he spotted the lampshade sitting on top of the heap, “like a cherry on top of an ice cream sundae,” “glistening” in the glow of his flashlight.

“Don’t ask me where I got the idea of what it was,” Dominici tells Jacobson. “But I’d been watching some Hitler stuff on the History Channel … You have to trust your instincts, know when something’s special … That’s why I say it was from Katrina. If it wasn’t for the storm, I never would have found it.”

Dominici showed the lampshade to Skip Henderson, a New Orleans friend of Jacobson’s, whose collecting of collectibles — Fender guitars, wristwatches, records — is a “life-defining joy.” Skip holds it in his hands.

Now he began to grok it, the material of the lampshade itself. The warmth of it. The greasy, silky, dusty feel of it. The veined, translucent look of it.

“What’s this made out of, anyhow?” Skip asked.

“That’s made from the skin of Jews,” Dominici replied.

“What?”

“Hitler made skin from the Jews!” Dominici returned, louder now, with a kind of goony certainty.

Skip bought the shade from Dominici. But owning the lampshade and contemplating its horror started to distress Skip and disrupt his sleep. He bowed out and sent it to Jacobson. “You’re the journalist, you figure out what it is,” he says to him.

So begins Jacobson’s globetrotting mystery tour to learn everything he can about his newly acquired “parcel of terror.” He starts at Buchenwald Concentration Camp in Weimar, Germany. “If you are interested in lampshades, allegedly made out of human skin,” he writes, “Buchenwald is the place.” While camp commandant Karl Koch “imposed a reign of relentless cruelty … marked by innovative tortures” at Buchenwald, his redheaded, “legendarily hot-blooded” wife, Ilse Koch, inflicted her own special brand of brutality. According to a US prosecutor at the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal, the “Bitch of Buchenwald” ordered tattooed human skin to be made into lampshades for her home.

There’s a problem, though, with the provenance of Jacobson’s lampshade. Even though DNA tests certify that it is indeed made of human skin, the skin is not tattooed. So, Jacobson agonizes. Could his lampshade really be an authentic Buchwald artifact, or could it be one of those “illusionary tchotchkes of terror, the product of Allied propaganda and the brutalized imagination of prisoners?”

The characters Jacobson encounters, as he travels to Germany and Jerusalem and hops back and forth from New York to New Orleans, add insight and color to The Lampshade. Among others, Jacobson seeks out neo-Nazi David Duke, “Louisiana’s most famous fascist,” who’s living “under the radar” in Germany and finishing up his latest book, Jewish Supremacism: My Awakening to the Jewish Question. He also interviews a Holocaust denier who calls himself Denier Bud.

“It is my goal to lead the Holocaust denier movement away from the stench of anti-Semitism,” Denier Bud tells Jacobson. “I don’t think the Jews should be punished or suffer unduly for continuing to spread the lie about what happened to them during World War Two. They were a society under stress, so it is easy to sympathize with their motives. What I’m looking for is a Jew-friendly solution to the Holocaust hoax problem.”

Distinguished Holocaust scholar Yehuda Bauer advises Jacobson to continue telling the story of the lampshade no matter how much or how little certainty about its origin he may finally uncover:

For Bauer, oral history was mutually beneficial to the teller and the listener. In the past decades, he’d heard so many stories. “Thousands of terrible stories, rattling around in my brain.” Some of these narratives were more revealing than others, but all of them, even the lies, had value. One day, however, the last survivor will die. Then, even though he and many other historians had written down the stories, finding the truth of things will become more difficult because the voices, “the sound of them, the voice of the teller, will never be heard again.”

The Lampshade is a multifaceted, indelible, and haunting tale full of silences and unknowns. Jacobson recognizes that the sweep and scope of human history is shaped by the interconnectedness of all things, and The Lampshade serves as a commentary on this “commonality.”

“As I stared off into the Buchenwald fog,” he writes,

I felt a connection between this place of terror, where the lampshade supposedly had come from, and where it ended up, in the New Orleans flood. The lampshade had its secrets, things I needed to know ….

But the inconclusiveness did place the lampshade in a unique, and possibly illuminating, existential position. Here was an example of an object that … had served as a most repellent symbol of racial terror, an icon of genocide. Yet it [may not] be possible to know who had died and who had done the killing …. The lampshade was an everyman, an every victim.

… It sounded insane then and it sounded insane now. But I had hopes, inchoate as they might be, that this purported symbol of racist lunacy, product of the worst humanity could conjure, might through its everyman DNA somehow stand as a tortured symbol of commonality.

It was just a thought.

Update, August 4, 2013: Edited and moved story from our old site to the current one.

Amy O'Loughlin Amy O’Loughlin is a freelance writer and book reviewer whose work has appeared in American History, World War II, ForeWord Reviews, USARiseUp, and other publications. She blogs at Off the Bookshelf.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content