Many magazines, InTheFray included, call their photographers, writers, and editors “contributors.” This was John Kaplan’s description when InTheFray published “Life after torture,” his photographic essay about victims of torture, last year. However, the word “contributor” extends beyond this one-time event to characterize what has driven Kaplan’s efforts over the past few decades.

“It comes from a psychological need to give something back,” Kaplan reflected. “I’ve gotten a lot of help along the way.” The 1989 Photographer of the Year began making pictures in his teens. “A group of extremely talented, yet giving people, were my mentors at a young age,” Kaplan said of the staff on his hometown newspaper in Wilmington, Delaware. Three of these photographers went on to work for National Geographic; two were awarded Photographer of the Year.

He felt very lucky. “As I became successful in my career, I felt a real need to give something back, to give people a leg up on their own path,” said Kaplan. “It’s been an evolution for me.”

After graduating from Ohio University in 1982, Kaplan spent the next decade photographing, designing, and editing for newspapers. In 1990, he founded a journalism consulting firm called Media Alliance. “Basically that was an outgrowth of wanting to contribute to the profession,” he said. “The goal … wasn’t focused on the business itself. It was focused on the education.” Kaplan shared his design, editorial, and staff development expertise with newspapers throughout New England, the South, the Midwest, and Canada.

This venture led to his becoming a fulltime educator. After first teaching for the Syracuse University London Centre in 1993, and leading countless workshops and seminars, Kaplan, who wanted to become a professor, returned to his alma mater for graduate studies in the late 1990s. Now a faculty member of the University of Florida, he was named the College of Journalism and Communications Teacher of the Year in 2002 and, in 2005, the International Educator of the Year. Just three years before, the Academy of Educators in Journalism and Mass Communication voted him second place in the AEJMC Promising Professors Competition.

In 2003, Kaplan developed a third way to help other journalists: through writing. He noted that university and workshop students asked the same sorts of questions over and over: “What are top editors and photo buyers looking for?” The need for a book emerged. No one had written a book about compiling a portfolio since 1984. Kaplan’s Photo Portfolio Success addresses a variety of photographic genres and media of presentation. Courses in several academic programs, such as the photojournalism sequence at the University of Missouri, use his book.

Through his teaching, Kaplan became involved with photographing torture victims. Among his workshop participants was a doctor who had treated these individuals. Kaplan contacted the Center for Victims of Torture, with whom his student had been involved, to discuss the possibilities of a photographic essay. “My idea was just basically to give a voice to the voiceless,” he said. “Torture was absolutely an under-reported issue when I approached it.”

Kaplan became one of the first journalists to go to new refugee camps constructed by the United Nations in Guinea after guerrilla war spilled over the border from Sierra Leone. Between 1991 and 2002, 50,000 people perished in a civil war in impoverished Sierra Leone, a country where a woman can anticipate living 42 years and a man 39. According to the BBC, a signature mark of one side was to chop off the hands of their enemies.

Kaplan’s plan for his two-week trip was to make a portrait of each victim, and record first-person accounts of what each had witnessed and endured. After introducing his project to various NGOs and other groups assisting the refugees, he had only six remaining days to photograph and interview. During that time he commuted four hours to and from the town where he stayed to get to the camps. By the time he was done, he had photographed 20 to 25 people. “I could have easily photographed a hundred if I [had] wished,” he said.

Reporting the darkness in human existence exacts an emotional toll upon journalists. Knowing this, Kaplan devised a plan to process his feelings. “I spent some quiet time alone every evening to really think deeply about what I’d witnessed, who I’d met,” he said. “I try not to distance myself emotionally.” When in difficult situations, journalists, like emergency and medical workers, focus upon the task at hand. There is a delicate balance of permitting feelings to guide, but not overwhelm, reporting. “While you’re photographing and while you’re interviewing, you do need a certain type of distance that allows you to concentrate, not to cry for example, and to maintain a sense of objectivity,” he said. “In my case, I do not believe in absolute objectivity, but I do believe in fairness. The best way to put it is you’ve got to keep your shit together while you’re working.”

Rewards for his efforts came in different ways. Kaplan had hoped that his documentation would be used to bring about justice for the torture victims, so he did not hesitate when the UN asked to use his work in the war crimes tribunal in Sierra Leone. Surviving Torture has been shown in Asia as well as published (as Life after torture) in InTheFray. Visitors to the Visa Pour L’image festival in Perpignan, France, were the first to experience the multimedia version.

Acclaim poured in from colleagues. In 2003, the project received the Overseas Press Club Award for Feature Photography and the Harry Chapin Media Award for Photojournalism, as well as citation by the Robert F. Kennedy Foundation. Survivors of Torture also placed in the National Headliner Awards, Best of Photojournalism Competition, Pictures of the Year International, Society of News Design, and the Photo District News Best of Photography Contest.

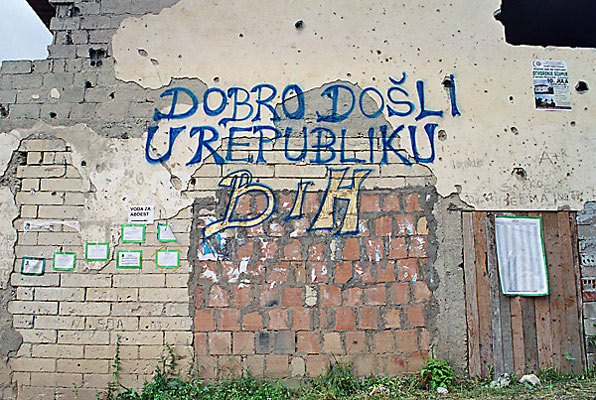

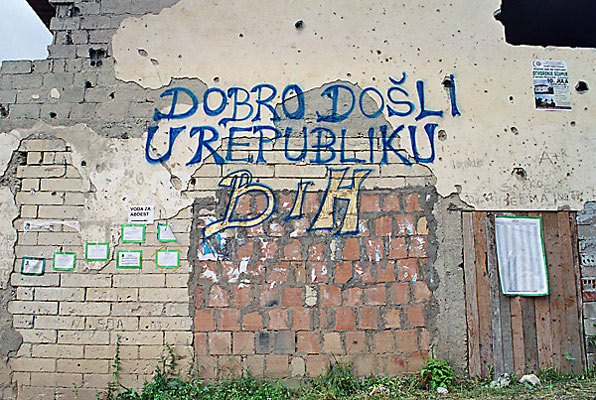

Observing that much renowned photojournalism executed in the past century focuses upon despair at some level, Kaplan recommends that photographers enlarge their vision. “I think the bigger issues need to be looked at,” he conveyed, noting that his two experiences judging the Pulitzer Prize helped him form this view. This is exemplified by one of Kaplan’s ongoing projects — documenting disappearing cultures around the world. (InTheFray published the three-part Vanishing heritage essay in its October, November, and December 2005 issues).

The use of torture is growing around the world, according to Amnesty International, Kaplan says. “What’s interesting to me about this topic is that at the time I pursued this a few years ago, torture was seen as completely apolitical. For example, if you asked members of Congress on either side of the political spectrum, you got a universal response of outrage against its use.”

“I believe that any rationalization of the use of torture in the greater war against terrorism is misguided to say the least, and stoops to the level of barbarism,” Kaplan adds. “It’s very shocking to see that in our culture we’re having a national discussion about its perceived use.”

In The Fray Contributor

Dear Reader,

In The Fray is a nonprofit staffed by volunteers. If you liked this piece, could you

please donate $10? If you want to help, you can also: