He rocks in his chair from excitement, and it creaks under his weight. Finally, Cameron, a young man who goes only by “C,” moves his white bishop across the board. He takes his opponent’s knight, smashes the button on the timer with the same hand, and taunts, “How you like that?”

The opponent, Big John, calmly takes C’s bishop with a pawn. It is an even exchange in terms of the pieces’ values, but it leaves John in a better position, controlling more of the center of the board. C stares at the board intently, and — for a moment, at least — is quiet.

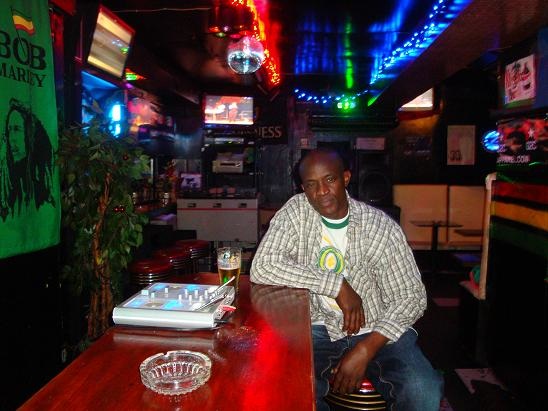

C has dark skin, bright eyes, and a neatly trimmed black beard. He is wide around the middle, and his loose-fitting clothes make him seem even larger. Every pound of C is filled with energy. He rattles off his words rapidly, and often berates opponents for poor moves (“What was that, what you thinking?”).

John Hill, forty-nine, who goes by “Big John” or just “John,” is a tall man with wide shoulders, whose grayish white stubble stands out against his dark face. He is soft-spoken and purposeful. He speaks unhurriedly, drawing out each of his words, even as he cracks lighthearted jokes. John reminds me of one of Tolkien’s Ents (the towering, mythical, tree-like creatures who are never rushed), while C brings to mind a 200-pound hummingbird.

John asks for a three-dollar donation for every game played, while C hustles, betting customers five dollars on the game’s outcome. John plays during the day, while C arrives in the park — New York’s Union Square — later in the afternoon, often playing until5 a.m.

John works the night shift as a security guard, his primary source of income. After work he might stop by home for a nap, but he then goes to the park to play chess, and does so on many weekend days as well.

C does not have a steady job, though he certainly does work. He plays chess in Union Square almost full-time. On days when the forecast predicts rain, C brings a large gym bag full of cheap umbrellas, which he hawks on the sidewalk. (“I got to get my money. It’s a recession! I got to get every nickel and dime. Every nickel and dime.”)

A few seconds pass before C decides on his next move — and is back to trash-talking. “You’re my fish, you’re my fish!” he yells, slamming the timer.

“No, you’re my fish.” John almost never goads an opponent, but C’s exuberance can be contagious.

“I’ve got you, I’ve got you. I’ve got you hooked,” continues C, moving a piece.

“Yeah, yeah — keep talking,” John answers, unruffled.

The onlookers, many of them street players or regular customers, watch with interest, grinning at the banter but keeping silent. Only after John wins do they begin commenting — “Oh, John, I thought you had him here when the pieces were like this,” or “Hey C, why didn’t you move here when he did this?”

After the game, C talks loudly about how in a real game John would have lost by a technicality — John had advanced his pawn to the last line of squares, but did not announce that he was promoting it to queen. John does not seem to pay C any mind. He just relaxes in his chair, triumphant.

The Game

Chess is one of the oldest board games in the world, originating in India about 1,500 years ago. In the centuries that followed, it was a game of kings, a pastime associated with high culture and martial strategy, played in royal courts in the Middle East and Europe.

But there is little that is regal about the men — and it is almost entirely men — who hold court today in Union Square and elsewhere, playing street chess for money. These men are public figures, who choose places of high visibility to sell chess games. In New York, they can be found in many parks or places of social gathering. They are a diverse group. Some are homeless, and some have jobs, apartments, and families. For some, chess is a vital — perhaps only — source of income. For others, the game is a hobby that provides additional cash. Some ask for straight donations. Others gamble, betting on the game’s outcome.

Big John has an apartment, a family, and a job, but he also spends hours every day outside, playing chess and smoking Newport cigarettes. He spends as much time in Union Square as one would spend at a full-time job. Street chess provides him with a small supplementary income, but he insists that he plays it in the parks because he loves the game. “Chess is the only sport — and I consider it a sport — that anyone of any height, weight, race, nationality, or even eyesight can do. It’s a level playing field,” he says. “Chess makes us all equal. It’s one of the things I love about it so much: that anyone can play.”

John has played chess ever since a childhood accident kept him home from school for a few years. As he grew up, he continued playing. For years he played in public parks — as a customer, playing against street players. As he began beating them, he decided to set up his own spot outside, to allow his “hobby to pay for itself.” He tried different places, including Washington Square Park and Times Square, but they didn’t have the right atmosphere. Finally, two years ago, John settled on Union Square.

The Cash Box

It is a sunny Saturday just before noon, the first clear day after a week of rain and snow. John has just arrived at Union Square and is setting up. He places a huge clipboard — the kind that art students use — on top of a cardboard box, to make a table. He drapes newspaper over upside-down plastic milk crates to make chairs. As he works, John leisurely starts to tells a story from his Brooklyn childhood, when he and some friends sneaked into an abandoned apartment building in their neighborhood.

Out of his gym bag John pulls a rolled-up mat with white and green squares. He straightens out the chessboard and clips one side of it to the clipboard. He takes a roll of tape from his bag, and slowly begins taping down his board.

It’s a new board, one that John recently bought from the Village Chess Shop, an iconic store in Greenwich Village that has catered to chess players for more than three decades. It is open all night and lets people play each other for $2.50 per hour. There you can find players of all kinds — grandmasters and children, street players and tourists. “It’s an equalizer — chess,” says Michael Propper, the shop’s owner. “You have a guy worth a million dollars, and you’ve got the guy with no home. And the big shot is the guy with no home, ’cause he’s a great chess player. And if he comes in here, he’s got authority, he’s got respect.”

Street players go to the chess shop mostly at night or when the weather is bad, especially during the winter. It provides a warm place indoors, but then their games are not as profitable, because they have to pay the house and because gambling is against the rules. (“There’s some subtle gambling that we overlook, that we know takes place, where they play for a couple of dollars against each other,” Propper says. “We have people who come here for thirty hours straight, and they’re clearly gambling.”)

Whether or not a street player chooses to play at the Village Chess Shop, he will still usually shop there. The chess shop, which also sells a $400 rosewood board, does steady business selling no-frills $8.50 chess sets to the park crowd.

John bought his new chessboard and set of pieces for twenty-five dollars, spending extra money to get heavier pieces that wouldn’t blow away in the wind and that wouldn’t break if stepped on. The color of John’s old set had also started to wear off, the white pieces turning beige from so much cleaning. Many street players make do with beat-up sets — one player uses a soda cap instead of a lost pawn, and C mixes pieces from different sets. But John says he’s aiming to attract customers. “Out here you always want to present something that’s desirable — new set, shiny pieces,” he says. “It just made more sense to go ahead and invest in a new set.”

Once his board is taped flat, John turns his attention to his cash box, the cardboard container that holds the day’s earnings. He tapes the bottom so it will hold, and he tapes down each of the four cardboard flaps so they will not be in the way. Then he reaches into his gym bag and retrieves yet another piece of cardboard. It’s a sign with John’s writing in blue pastel: “If you take a photo of the chess players please leave a donation.”

He tapes the sign to his cash box at an angle, so that the sign can flip down. That way, it can act as a lid and cover the contents of the box if a park ranger walks by. (While the authorities generally tolerate street players, gambling on chess is technically illegal, and players have been known to be hassled or fined wherever money overtly changes hands.) The cash box itself can be disassembled and reassembled fairly easily — if, for instance, skateboarders keep bumping against it.

John reaches into his bag again for a piece of purple checkered fabric, which he uses to line the bottom of his cash box. He dumps a handful of his own dollar bills into the box; this will encourage other people to donate. It’s one of the many tricks that John has picked up over the years to increase his chess income. But he does not live on what he earns in the park, nor could he. “I tend to do okay: maybe forty, fifty bucks,” he says. “A great day for me would be around eighty dollars.” But that’s just “once in a blue moon,” John adds. “This in no way is like a great windfall. You eek out a few dollars here or there.”

One reason that John makes less than some of the other players is that his prices are so low. Most players charge five dollars for games, but John charges just three dollars — to “make it inviting,” he says. “You make it affordable, where someone can actually enjoy the game if their game is not that good — someone who plays for, like I said, the love of the game.”

Finally, John pulls out his new set of weighted chess pieces, along with a sleek digital chess clock. As he meticulously puts each piece in its place, he nears the end of his story, too — this now twenty-minute chronicle of John when he was eight years old, exploring an empty apartment in Brooklyn with his friends. They were poking innocently around the rooms, John says, when suddenly his world turned upside down.

“I didn’t know what happened,” he says. “And then my friend looks at me, and he starts screaming.”

Putting down the rook he’s been holding, John whips off his cap. His silver hair is cut short, almost to the skin, making his head look like a grizzled coconut. He takes my hand and runs it along a deep groove in his skull — a scar from where a falling brick embedded itself in his head decades ago. After his accident, John remained housebound for a few years. Stuck inside, he would look out the window at kids playing outside and wish he could join them. This was the time of his life when he learned chess.

I find myself wondering where this story started: what question had I asked to provoke the twenty-minute tale? It was like John Nash in A Beautiful Mind, taking twenty minutes to answer, “Would you prefer coffee or tea?” Then I remember: earlier I had marveled that John was not tired, coming straight to the park from his graveyard shift as a security guard. His story, throughout which the mantra “enjoy life” was repeated, was an elaboration of his answer: “I like the sunshine.”

John finishes setting up his pieces. Nearby, other street players are yelling their catch phrase — “Do you play, sir?” — to passersby. But John just leans back on his crate. Behind him, the park’s performance acrobats have drawn a large crowd, their stereo blasting pop reggae. John bops his shoulders to the beat, grinning.

The Players

A few hours later, John is still in good spirits. He has played a few games against the pedestrians who have dribbled in through the afternoon, and is now sucking a lollipop and playing Mike Koufakis. Mike is an eight-and-a-half-year-old whose feet dangle from his milk-crate seat, inches off the ground.

“Oh, heeeeey. He’s got me now. That’s not nice, that’s not nice.” John makes a show of mock defiance. “They sent me a ringer.”

Mike is playing well, but making mistakes. At one point he takes John’s bishop, leaving his own white queen in jeopardy. John slowly puts his bishop back where it was and taps the white queen to alert his opponent to the danger.

“How long has he been playing?” John asks Mike’s father.

“Two years,” replies Steve Koufakis.

“He’s good. He rushes, though.” As John waits, he scratches a lottery ticket with a dime. “Most of his mistakes are because he rushes.”

After John checkmates Mike and shakes his tiny hand, Mike’s father throws three dollars into the cardboard box by the table. As Mike gets up, a twenty-something man sits down. This customer is a regular.

“ I do now have a small gallery of repeat customers, ’cause I’ve been here a little while,” John says. “Most of them work in the office buildings, so they’ll take their lunch when their business is done.”

Regular customers are a vital part of street chess, but can also be a source of tension: poaching customers sometimes causes conflict. Once, another street player yelled at John for playing a steady customer. “He goes, ‘Traitor, traitor!’” John says. “It’s like, ‘Oh, you play with me.’ And it’s like, ‘Well, you know, you don’t own anybody.’”

Street players are protective of their regular customers and encourage them to come back. John asks a lower price of his regulars — two dollars instead of three. Another way that street players ensure steady business is to let their regulars win occasionally. Not everyone does this, but many do. John says that letting regulars win keeps up their morale, encourages them to keep playing chess, and ultimately teaches as well. “It’s a customer-by-customer judgment,” John says. “I enjoy this, so I try to make it enjoyable for the people I’m playing.”

For players like C who bet five dollars on a game’s outcome, letting a regular customer win once in a while is seen as a cost of doing business. After “I beat them enough where they get frustrated,” then C will consider throwing a game, he says. “Sometimes you have to give a little to make a lot. I give them five bucks, but I’ve won fifty, sixty from them.” On the other hand, some regulars are so good that they don’t need to be given wins. But hustlers like C cannot afford to play too many players like these.

Besides repeat customers, John also has repeat onlookers he recognizes. “He’s a professional watcher,” John jokes after one man refuses a game but hangs around anyway. Half-circles form around particularly intriguing or lively chess matches. These are mostly composed of interested street players, friends of customers currently playing, and customers waiting for a match. If a child is playing, this draws a particularly large crowd. John does not mind onlookers because they might evolve and “become customers,” and also because crowds cause curiosity and generate business. John compares having a crowd of onlookers to “advertising.”

The crowd is also good for any nearby street players. As Big John plays, the player next to him — also named “John,” but smaller — asks the onlookers if any of them would like to play. This is one of the reasons that chess players who are friendly with each other congregate together at the park. Another reason is security: John often asks adjacent players to watch his things if he has to run across the street to use the bathroom at Whole Foods.

Rules of the Game

In the afternoon Big John is quietly engrossed in a match when a booming voice behind him announces, “The General has returned.”

“I’m back, I’m back!” C whoops, making his entrance.

“Heeeeeaaay,” John drawls, shaking C’s hand. “Where ya been?”

“Oh, you know, you know — around,” replies C, slapping hands and doling out one-armed hugs to the other players. C grabs a seat next to “Little John,” and the two begin playing.

C plays other street players, which is rare in their world. “It’s not that they have anything against each other, it’s just that some people don’t want to tip their skill level to the other player,” John explains. “If you have a bunch of people who have tables set up, one may be better than the other, a couple might be better than the rest. If you begin to play each other, then the other people know, ‘I’m better than him, I’ve played him.’ And a rivalry will begin like that. A lot of people can’t take a loss.”

When he was a street chess customer, John played all of the Union Square players. But after he set up his own spot in the park, the rules of social interaction changed — he could no longer play against other street players. “That’s like bothering someone’s other stand,” John says, motioning to the nearby Union Square vendors selling art and souvenirs. “You have a stand and you’re working. Tend to your business and let him tend his.” The only street player John will play is his friend C — and only when there are no paying customers. “Yesterday me and him played most of the day because it was real slow — I think I had like two participants all day.”

When C does play street players, he is very conscious of the difference in roles. If playing on his own board, he may stop a game at a moment’s notice if a customer shows up. But if C is playing another street player on that person’s board, he is even more hyper-aware of potential customers. Normally C might try to solicit a game from every fourth or fifth passerby, but when taking up a customer’s seat, C will ask almost every lingering pedestrian, “Do you play?”

“Do You Play?”

C looks up from his match with Little John. A young couple with cameras is watching the game.

“Do you guys play?” he asks them.

The woman shakes her head, and the man walks away. C shrugs and returns to the game. Less then a minute later an old man pauses as he walks by, and C immediately yells out, “You play, sir?”

As a means of soliciting customers, “Do you play?” is significant in that it is designed not to close conversation. If a passerby answers “Yes,” then the chess player invites that person to sit and only then — once it is more awkward to refuse — brings up money. But even if the potential customer answers “No,” the lines of dialogue remain open.

As a young woman in a college sweatshirt walks by, C asks, “Do you play?”

“No,” she answers, smiling.

“Want to learn?”

She shakes her head and walks away. But C’s follow-up question is fairly standard for street players. Dozens of times a day, the player switches roles — from a worthy adversary offering a challenging and fun match, to a patient teacher willing to impart his expertise.

Street players often do teach chess; during the summers John has parents who pay for weekly lessons for their children. But John points out that he is still learning, too. Even though they play chess for hours every day, he and other street players still actively try to improve their game. C says he occasionally pays for a chess tutor, and John keeps his skills sharp by playing bullet chess with one of his regular customers, for a reduced price. Bullet chess is an especially intense form of speed chess where each player has just one minute on the clock. (In most speed games played on the street, players have between three and ten minutes.)

The Endgame

It’s around eight in the evening, and John is putting away his set. He places all the black pieces in one Ziploc bag and all the white pieces in another, and wraps both baggies in a cellophane grocery bag that he stows in his gym bag. Then he slowly removes the tape holding his chessboard to the clipboard. He rolls up the mat into a tube, secures it with a rubber band, and puts it in another cellophane bag. He takes out his Walkman CD player, wraps the headphones around it, and places it in his jacket pocket. As he puts his things in order, John talks in his meandering way about how the cost of movies has risen since he was a child.

John turns his attention to his cash box. He scoops out all the dollar bills and stuffs them into his pants pocket. “I usually don’t count till I get home,” John says. “I find it’s bad etiquette.” But he guesses it was a fairly average day, netting about forty to fifty dollars.

John removes the cloth lining from the bottom of the box, and several coins clink free. (Some tourists, seeing the sign asking for donations in exchange for photos, drop loose change instead of dollar bills.) John sighs as he reaches down to pick up a nickel, a dime, and several pennies. “I used to have a dollar sign on the box,” he says. “I might put it back up.”

He folds the cash box flat, while keeping the sign attached to it. Then he lifts the clipboard off the larger cardboard box that made the table, and folds that, too.

He shakes hands with the other street players who remain, and gathers up the two folded boxes, the clipboard, and the two plastic milk crates. He walks to the west side of the square, and slides the boxes and clipboard snuggly between a wall and a recycling bin. He hides the milk crates behind a statue.

Big John adjusts the strap of his gym bag, then stretches out his large hand. “I’ll see you when I see you.”

As he walks away he turns and says, over his shoulder, “But, you know I’ll be out here tomorrow.”

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content