On a Friday afternoon in early February, 16-year-old Jessica Kjellberg is navigating the crowds at New York Comic Con, the giant annual gathering of comic fans in New York. She’s heading back to her special gig at the Griffons [sic] Claw Armory booth, a New Jersey–based purveyor of steel swords, as well as more fantastic movies and comics-inspired weapons. In an effort to look vaguely medieval, Jess, who has wide-set blue-green eyes and an athletic build that hints at the many hours she spends practicing kung fu and sword-fighting, is wearing tight black pants, black lace-up boots, and a black corset-style top embellished with red embroidery.

Jess had come across the company’s booth at a previous convention and, impressed by the quality of the steel broadswords, asked to help out. She’s not sure what she’s being paid, but money’s not the object. She just likes being part of the action. Many of the other teenagers at the convention, which attracts people from all along the East Coast, are playing hooky. Not Jess — even though she’s been setting up the booth since 9:30 that morning. She and her twin sister, Caroline, live in the East Village with their mother, who runs a luxury skincare company with the girls’ aunts, and their father, a copyright lawyer, who performs in a band on the side. The twins haven’t been to school since third grade.

Technically, the state of New York considers Jess and Caroline homeschooled, but that term, with its connotations of conservative Christians chanting Bible lessons at the kitchen table, or parents drilling their offspring in preparation for the National Spelling Bee, doesn’t capture what the twins actually do. For lack of a better term, Jess and Caroline describe themselves as unschooled, which is to say that they — and not their parents — decide what, when, and how they will learn.

This year, Jess is doing several school-like activities: Latin and math lessons with tutors, an introductory sociology course at Hunter College, and a lot of reading (she’s up to “J” — Julius Caesar — in The Complete Works of Shakespeare). She gets excited talking about, for example, how Latin is like a puzzle, but she confesses, “Weapons are my life.”

Last year, Jess spent between three and eight hours a day training one-on-one with her martial arts instructor. The year before that was largely spent hanging out with The New York Jedi, a group that performs Star Wars–inspired light saber battles at events like Comic Con. The Jedi have a show this afternoon, and a member of the group stops by the Griffons Claw booth. He’s dressed in a floor-length black leather coat and has a vague Kiss-like look — white face, black clown lips and eyes, crazy hair with sparkles. He complains he doesn’t see Jess enough. She brushes that off, but the fact is, she’s been focusing a lot on academics this year, plus training a lot in martial arts and taking up fencing.

“I’m just going to give you a call at like, 2:00 in the morning,” he says, half-joking.

Jess smiles and does some excited little bounces. “Do it! Do it! Do it! I love spontaneity.”

An adjustment for parents

An hour or so later, Isabel Ringer, Jess’s 12-year-old friend and martial arts student, bounces up to the booth, with her mother, Kayte Ringer, trailing behind, looking tired. Isabel, a tiny, pixie-like girl with green eyes, fair skin, and a heart-shaped face, quit school two days ago. She can’t stop grinning as she chats with Jess about a cartoon portrait she’s had done at another booth and about the history of Japanese weaponry — many have their origins in farm tools, Jess explains, because for centuries only samurai were permitted to carry swords.

On day three of the no-school experiment, Kayte says she feels like she’s flying by the seat of her pants. Jess, who Kayte calls “our heroine mentor,” has been talking up unschooling, and Isabel likes the idea, but Kayte isn’t sold yet. It heartens her, though, that Isabel’s stomachaches and migraines have already vanished.

“I see how happy she is,” Kayte says, gesturing to her daughter, who is still absorbed in conversation with Jess.

Isabel had languished at school for years and had been begging for an out, especially after starting martial arts lessons with Jess. She didn’t mesh well with either the cliquish kids at a prestigious progressive school on the Upper East Side, or the learning-disabled ones at another private school. For the past five years she had suffered from chronic stomachaches and migraines that Kayte, after putting her through a battery of medical tests, finally chalked up to anxiety. But Kayte, a single mother who runs an integrative body therapy practice, called Rolfing, out of her West Village apartment, could not see how she would find time to homeschool Isabel. Then, at a parent-teacher conference a couple weeks before, the teacher said Isabel, who is a night owl and would arrive at school exhausted, seemed out-of-it and “traumatized.” Kayte had had enough.

“All they kept saying was, ‘she’s too fragile,’” she says. “And I’m like, ‘well, maybe we’re too sensitive for school.’”

In honor of the convention, Isabel is wearing a royal blue fake velvet cape that trails behind her as she walks, a choker with a large sleigh bell attached, and a fleece hat with floppy bunny ears. She’s supposed to be a Sith, one of the Star Wars “bad guys.” Despite a battery-operated light saber bought at last year’s convention, she doesn’t look remotely menacing, though she seems entranced by the weapons in the booth, running her hands over a mock dagger, which Jess offers to buy her. Kayte makes some mild protestations about having weapons in the house, but Isabel grins and says, “It’s not your house, it’s my room!”

Kayte pauses and sighs. “This is all so new to me.”

She seemed to be talking about the world of Star Wars, comics, and martial arts enthusiasts, but she might have been talking about unschooling, too.

Helping kids find their milieu

As schools nationwide have cut recess, mandated weeks of test preparation, and lengthened the school day in the name of accountability, unschoolers seem to take pride in going against the grain. They champion flexibility, creativity, and so-called “child-led learning.” Some eschew textbooks, grammar lessons, workbooks, tests, and anything else that resembles school. At its core, though, unschooling is about helping kids find their own milieu rather than requiring them to fit in with a school’s rigid structure and norms. If that milieu is plodding through workbook after workbook, then so be it.

No one knows how many families unschool, because no national agency collects such statistics and because unschoolers themselves debate what constitutes “real unschooling,” since each family’s approach varies. The number of children educated at home, however, has risen from an estimated 850,000 in 1999 to 1.5 million — or nearly 3 percent of the school-age population — in 2007, the last time the U.S. Department of Education surveyed parents and kids. The survey does not ask about unschooling in particular, although advocates of unschooling maintain their approach is growing more popular.

Homeschoolers of all stripes credit John Holt, the educator and advocate of progressive education who coined the term “unschooling,” with starting the modern home education movement some 30 years ago. But until recently, unschoolers stayed largely beneath the radar. New York University sociologist Mitchell L. Stevens, in a seminal academic study of homeschooling, argues that in the 1990s conservative Christians came to dominate the movement, not so much because they constituted a majority, but because they formed efficient, well-organized advocacy groups that skillfully explained their methods to legislators and the media.

In the past two decades, however, unschoolers have grown more visible. A genre of unschooling self-help books, online forums, websites, and blogs has sprung up, with parents detailing their experience and offering advice to others. Annual unschooling conferences for parents and kids attract hundreds. For teenagers, books like the The Teenage Liberation Handbook: How to Quit School and Get a Real Life and Education by former middle school teacher and unschooling advocate Grace Llewellyn advise kids to take control of their own learning.

Llewellyn also runs the Not Back to School Camp for teens aged 13 to18, which boasts no set bedtime, very few mandatory activities, and a self-consciously tolerant outlook. Both Jess and Caroline Kjellberg have attended. Like their peers, unschooled teenagers congregate in Facebook groups and post YouTube testimonials. One teen, putting a self-ironic twist on a sometimes-voiced criticism of unschooling’s laissez-faire approach, calls her blog “I’m Unschooled. Yes, I Can Write.”

The Internet, of course, has encouraged subcultures of all sorts. It has also subtly normalized one of the basic tenets of unschooling: that pursuing one’s own interests, however narrow, is both worthwhile and doable. Even as public schools push for accountability and the college admissions process grows increasingly cutthroat, the Web is ushering in a new wave of amateurism and, perhaps, a renewed respect for the autodidact.

In recent decades, the concepts of self-directed learning and multiple intelligences have gained mainstream acceptance, while books like Richard Florida’s The Rise of the Creative Class champion the cluster effects of a deep and talented pool of creative workers, demonstrating how they help shape the character of a city and define a lifestyle. In parts of Brooklyn and Lower Manhattan, where coffee shops are packed with freelancers, many scarcely a decade older than Jess and Caroline Kjellberg, tapping on laptops and jabbering on iPhones, one might wonder whether, for a certain kind of kid, school may be obsolete.

An unconventional education

Eighteen-year-old Cullen Golden may well be that kind of kid. Except for the fact that he lives with his parents and nine-year-old sister in their apartment in the East Village, he could be any of the thousands of young, aspiring filmmakers in New York City. He collaborates with homeschooled and unschooled friends on goofy but imaginative short videos that he uploads to YouTube and posts to his website and Facebook page. With his fellow unschooled friend, 17-year-old J.T. Schafer, Cullen has been working on a Lord of the Rings–style film they half-jokingly refer to as “The Epic Movie” for three years. They filmed it last summer at Cullen’s parents’ house upstate, but have to reshoot. After some prodding, they confess they forgot to turn on the button on the camera that would allow them to play the film in widescreen, a must for picture quality. Also, Cullen, who for the past couple of years has taken playwriting classes at the MCC Theater, a hip off-Broadway venue in Manhattan, thinks the script needs reworking.

Cullen, who has round blue eyes, a gap between two of his top teeth, and long reddish hair he often wears in a ponytail, has never been to school. His parents, Lori Johnson and Joey Golden, who had moved to New York from Detroit to pursue acting careers, settled on unschooling by accident, after deciding, Lori says, that sending Cullen to school felt like saying, “Here, raise my child for me.” (Although both Lori and Joey acted extensively when Cullen was young, Joey now works for a firm that designs websites for big businesses and nonprofits). At first, Lori tried to make Cullen do spelling and math worksheets. It never worked — there was always something more interesting.

“Every year,” Lori says, “we’d be like, ‘It’s March! Should we be trying to do something that looks like school?’”

After Cullen’s younger sister Addie was born, things got more hectic. Cullen did all kinds of activities, from soccer to avant-garde dance, but throughout, he’s been able to pursue filmmaking with an intensity he doubts would have been possible if he had gone to school or if his parents had insisted on a more structured homeschooling approach. In addition to filmmaking and playwriting, he plays in a guitar quartet; composes flowing, lyrical guitar pieces, as well as some more satirical ones; and shoots stylized photos of cityscapes and nature scenes. He also plays a lot of video games, something his mother has learned to live with. In addition to playing them, he’s the “ideas guy” for J.T., a computer whiz who designs his own games. For awhile, Cullen studied with a math tutor whom he raved about, but last year got too busy.

Cullen knows he’s had an unconventional education but acts nonchalant about anything he may have missed. If he doesn’t know some things high schoolers are expected to have learned, he says, “It’s not lost. It’s not like [because] I didn’t learn it when I was little, now it’s all over.”

Unschooling not an excuse to sit around all day

The notion that learning continues after childhood or adolescence is not a radical idea. After all, an entire industry of for-profit and not-for-profit continuing education programs rests on that premise. Unschoolers are full of anecdotal success stories about brilliant kids who did not learn to read until their teens (Cullen, his mother says, did not read confidently until age 11), but researchers have no data with which to measure how unschooled children perform academically compared to their peers or how they fare in later life. Some states — New York included — require homeschooled children to take standardized tests in certain grades, but the federal government does not collect that data, so there is no way to know on a national scale whether encouraging children to learn at their own pace hurts them, helps them, or makes no difference at all.

Because of the lack of data, experts hesitate to draw sweeping conclusions, but they do say that unschooling’s potential to give a kid either a great, diverse education or a limited and weak one depends a lot on the family’s resources. That’s hardly surprising — there’s lots of data correlating SAT scores with parental income. Maurice Gibbons, an early and influential champion of self-directed learning and the author of a 2002 manual on encouraging high schools to take charge of their education, raised that concern.

“If you have a really rich home life and lots of activities and lots of books around and lots of materials, I could see that as a fascinating possibility,” he said. On the other hand, he said, “I wonder how someone living in the projects, how they would do with unschooling.”

There’s also the question of geography. The Internet has undoubtedly made it much easier to discover and explore diverse passions, but having ease of movement and access to the resources of a big cosmopolitan city such as New York helps a lot. Being old enough to get around by oneself expands one’s choices, too. Even the most ardent unschooling parent has to broker compromises between siblings. Jess Kjellberg, for example, can hop on the bus from New York to Philadelphia to visit her boyfriend. Her friend and Latin buddy, Joe Lodin, 16, never attended school, but he pegs the beginning of his unschooling to when he could get around by himself, often catching the train or the bus from Westchester to Manhattan.

“Now,” he says, “I will consciously think I have an interest in x, and then I will do all the research on x and then see if x is available in a class nearby.”

Most of the discussion of unschooling in the popular media has focused on younger children, perhaps because reading and basic math remain such touchstones in education policy. But unschooled teenagers occupy a fuzzier terrain. On the one hand, adults tend to think of teenagers as self-absorbed and hormone-addled. On the other hand, it’s not beyond the pale to think that self-motivated teenagers might take it upon themselves to, say, study Latin, as Jess Kjellberg and Joe Lodin have, or delve into anarchist political economics and music theory, the way Caroline Kjellberg has. The question is whether this laissez-faire approach can work for just any kid.

Gibbons suspects not. As kids get older and parents get more hands-off, he says, “It really does leave all initiative and methodology and direction to the individual student.” Some teens, just like some children, are capable of challenging themselves, he says, but others many need a push.

Grace Llewellyn turns that argument on its face in her 1991 book The Teenager Liberation Handbook. Teenagers, Llewellyn writes, are inherently creative and motivated; they just need to channel their energies. They are also a lot more levelheaded and reasonable, Llewellyn says, than adults give them credit for. Caroline Kjellberg puts it more bluntly. Unschooling is not, she says, “an excuse to sit around all day eating Cheetos and smoking weed.”

Still, can’t having near-total control over one’s schedule feel kind of overwhelming?

“I’m perfectly capable of handling it — everyone my age is perfectly capable of handling it,” Caroline says, pointing out that, until a little more than a century ago, girls her age were getting married, starting families, and heading households. That’s a long row to hoe compared to deciding whether to do some computer programming or go to play rehearsal.

What about college?

To say that unschooled teenagers have a lot of control over their schedules is not to say that every moment is a pleasure, though you might get that impression from reading the popular unschooling guides.

“They talk about how wonderful every day is because they’re very unstructured,” Caroline Kjellberg says. “And [how] every day they get do to these fabulous things and every day they’re so happy to be alive.”

The reality, she says, is that unschooling is just life. Sure, it’s great to decide what you want to do, but there are days when things don’t go your way. She wishes unschoolers acknowledged that more often.

“Everything is supposed to be this very, very loose, extreme hippie kind of thing, and if you’re not like that or if you have days where you think maybe it’s not the best thing, it can get kind of confusing,” she says. “’Cause it can be like, ‘well, am I a real unschooler? Well, if I was a real unschooler, would I be like this?’”

Jess is more of an evangelist, though she’s under no illusion that unschooling is all endless joy. There’s something to be said for delayed gratification, for doing things now that will help you out down the road.

“I know there’s a lot of stuff that, like, I need to know and should learn,” she said one day last fall, shortly after plunging into algebra and world history courses after a year off from doing martial arts (she later dropped the world history, which she deemed too much busy work). “I’ve sort of waited until now, but I’m really motivated. This is the most academics-heavy year I’ve ever had,” she added, giggling, as though it were almost a little silly. “But I love it.”

Jess has since decided she wants to enroll in Hunter College next year. The SAT math is not her strong suit, so she has enlisted her Latin buddy, Joe, to tutor her at a pizza place in Morningside Heights. After a year at Hunter, she hopes to transfer to Brown University — she likes the idea of having no required classes. Her sister, meanwhile, is taking advanced placement courses in English composition and American history, in part because she appreciates having something to keep her on track, but also to earn some “completely, indisputably objective grades” to show to music conservatories when she applies next year.

“The fact that you took a class doesn’t mean you know anything. It just means you took a class,” Caroline says, but that’s the way college admissions works. To get in, both girls know they will have to play the game.

Cullen Golden isn’t sure he wants to play the game. At 18, most of his peers, even the ones who are unschooled or favor relaxed homeschooling, have already applied to college. Recently, while Cullen, J.T., and two other friends were hanging out, the conversation turned to college admissions. At his parents’ urging, J.T. said he had applied to 10 schools, though he expected to defer and was holding out the possibility of pursuing an as-yet-undetermined “big project” instead of college. Cullen kept quiet throughout the conversation. His eyes darted a bit, like he didn’t want to have to do any explaining.

Asked about it later, Cullen sounded more confident. He’s considered film school, but is not sure it’s necessary and has yet to take or prepare for any of the admissions tests many schools require. Last fall, he and his mother scoped out the acclaimed Tisch School of the Arts at New York University, where they viewed some student films. Cullen was underwhelmed.

“They seemed very planned out, very basic,” he said. “That was kind of weird because I was like, ‘What are you teaching them?’”

He figured he would wait it out, see what he could keep learning on his own. His playwriting teacher is giving him help on how to write a screenplay and, on the suggestion of a friend’s filmmaker father, he sent his resume to a film production company, hoping for an apprenticeship. Cullen’s mother, Lori, isn’t sure her son needs to go to college, either, but she does not want him to feel he can’t go.

A couple of years ago, when kids his age were frantically cramming for college admissions tests, getting expensive tutors, and memorizing test-taking strategies, “it just seemed like ‘what a weird thing to do,’” Lori says. “But that’s almost an unfortunate thing because maybe it closed some doors for him.”

Cullen frames the issue differently. “It is interesting,” he said recently. “Some of the people I know who aren’t in college are kind of not really doing anything.” He doesn’t want that, but says as long as he has projects like the Epic Movie he and J.T. are working on, he’ll be fine.

“I think the best thing to do is keep pushing forward,” he says. “Just keep doing stuff.”

Ever-changing interests

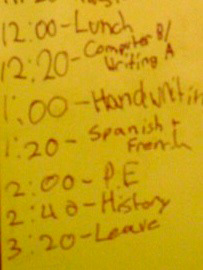

The week after the comics convention, Jess Kjellberg and Isabel Ringer have arranged for a martial arts lesson. They used to meet at a regular time, but since Isabel left school, everything is up in the air; they finally settle on 5 p.m. A friend of Isabel’s from camp comes along. The winds are gusting past 30 miles per hour, so their usual sparring on the pier a block from Isabel’s apartment will be too difficult. The girls traipse upstairs to the apartment, which is large for New York standards, and drop staffs, sticks, coats, and a steel broadsword on the living room couch.

While the girls spar, Isabel’s mom, Kayte, goes on the computer and scrolls through the homeschooling paperwork she has to file with the state. She has no idea how to do it and was up half the night reading books on all different kinds of homeschooling. They’re stacked on the kitchen table, along with some classics she hopes she and Isabel can read aloud together: Tom Sawyer, The Jungle Book, and others by Hans Christian Anderson. Jess, who’s letting Isabel and her friend practice on their own for a bit, spots The Unprocessed Child, a mother’s memoir of unschooling her daughter which she had lent Kayte. “Go unschooling!” Jess says, with only a tiny trace of irony.

Kayte says she doesn’t know what to do. It’s day seven of the no-school experiment.

“It’s more me. She’s better adjusted to it. She’s fine with it,” Kayte says. “She acts happier by the day.”

After a bit, Isabel and her friend scamper upstairs so Isabel can put on black kung fu pants to match the ones Jess is wearing. Jess browses martial arts videos on YouTube while Kayte hovers, waiting for her next client.

“She told me today she hates workbooks,” Kayte says of Isabel, sounding at a loss.

“Yeah, I went through a phase like that,” Jess says, nonchalant.

“I left a note by the computer,” Kayte says, “saying ‘Do you want to write an essay on Jane Eyre?’”

On the wall behind the computer is a big poster that reads, “Isabel’s Home School Wish List.” French, piano and voice lessons, cooking, a fashion design project, martial arts with Jess, the city homeschool association’s spring play, gymnastics, lots of other stuff. Isabel has amended it to include pottery lessons and “band” — the rock group she plays in with two girlfriends. Kayte inspects it.

“We were going to do another one, because it’s already changed,” she says.

Jess doesn’t miss a beat. “It always changes,” she says.

Two weeks later, things have indeed changed. Isabel kept amending her wish list until it spilled over onto sheets of paper that have collected on the piano bench.

“I can’t really make up my mind,” Isabel explained. “I get really excited about one idea, and then that leads to another thing and that leads to another thing.”

Reading about the Greek god Dionysius recently, she stumbled on something about a potion and immediately became obsessed with mixing imitation versions in preparation for her magic potion–themed 13th birthday party next month. Kayte, though, had been waking up at 3, 4, and 5 in the morning, worrying. Her attempts to spark an interest in “the classics” had fizzled, finally, with Gulliver’s Travels.

But seeing Isabel sit still for hours, stringing intricate beaded charms to decorate the potion bottles, Kayte felt better. She’d rarely seen her daughter focus like that before. She reminded herself that Isabel had started reading and writing stories for fun, and now, was asking about computer graphics lessons at the huge Apple store down the street. They made a big pot of chili, and Isabel, who hadn’t had an appetite for months, kept going back for more.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content