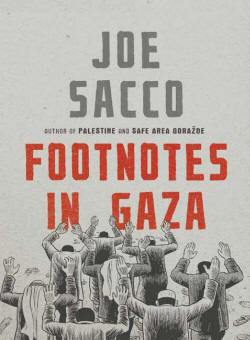

The massacres of 386 Palestinians in two Gaza Strip towns—Rafah and Khan Younis—by Israeli soldiers in 1956 have not left much of an imprint on history. At the time, the media was preoccupied with the Suez Crisis, and as a character in Joe Sacco’s new graphic novel Footnotes in Gaza laments, Gaza is a place “where the ink never dries” before the next calamity happens. Footnotes is Sacco’s impassioned attempt to set the historical record straight, to make the massacres more than a footnote.

“History can do without its footnotes,” he says. “Footnotes are inessential at best; at worst they trip up the greater narrative.”

Sacco himself only learned of the massacres from a brief mention in The Fateful Triangle, Noam Chomsky’s indictment of America’s pro-Israeli policies that was published in 1983. In 2003, he returned to Gaza—where he had previously traveled on assignment for Harper’s during the second intifada—to investigate the killings. Footnotes draws from his interviews with witnesses and survivors, examinations of Israeli archives, news stories, and United Nations photos.

Like Art Spiegelman (Maus) and Ed Piskor (Macedonia), Sacco is a master of what could best be described as “graphic journalism,” his two previous books—the award-winning Palestine and Safe Area Goražde—also using the form. In Footnotes, he alternates images of Gaza in the 1950s with images from present-day Gaza. One drawing, for example, shows neat rows of houses that made up a refugee camp in 1956; that is contrasted with an image of the same camp today, rocks holding down shabbily built roofs, a sea of satellite dishes on top of them. Similarly, when Sacco’s Gaza subjects tell their stories, images of them in the 1950s are juxtaposed with images of them now, their faces showing the toll of a hard life.

Sacco’s method has a tremendously compelling quality, in that his juxtaposing technique evokes a sense of what might have been, as readers grapple with the subjectivity of each storyteller’s memory. In one scene, Gazans debate over when exactly a family member died and was buried. Their memories are eroded from the passage of time—and from pain. The technique also evokes a sense of continuity, weaving together the past and present, and demonstrating the inexhaustible nature of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

As if to demonstrate just how intertwined the past and present are in Palestine, Sacco touches on the death of Rachel Corrie, an American activist who was run over by an Israeli Defense Forces bulldozer while she protested the demolition of a house in Rafah in 2003. On the same day that Corrie was killed, Ahmed El-Najjar, a Rafah resident, was shot by Israeli forces in the head, chest, and leg, reportedly while standing in his own doorway. As Corrie’s body lies in the morgue, surrounded by the flashes of photojournalists’ cameras, El-Najjar is left alone by the media, tended to by only his family. “The killing of a Palestinian in Gaza is a routine occurrence,” Sacco observes. “His loss will cause not a ripple outside of his immediate circle of family, friends, and neighbors.” In one chilling image on one page, Sacco expresses the book’s message: death and destruction are so commonplace in Gaza that the details become simply footnotes, existing only in the memories of Gaza’s residents.

If one aspect of Sacco’s work must be criticized, it might be his apparent inability to leave anything out. Footnotes in Gaza is 432 pages thick (compared to Palestine, which comes in at only 288 much narrower pages) and, at times, feels cluttered. Fortunately, it’s split into sections and can easily be read piecemeal once the reader passes the introduction.

Footnotes does not provide a broad history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, nor does it answer any of its big questions. And though it is not a sequel to Palestine, those without much knowledge of the intricacies of Israel’s and Palestine’s histories would do well to go back and read Palestine first. But Footnotes provides an intimate look into the lives of ordinary Palestinians whose memories of 50 years of conflict are permanently ingrained into their outlook on life. It is one man’s take on the reality of Gaza, brought to vivid life by his unique brand of comic art.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content