To put it bluntly, the past few years have been exhausting. That’s been all the more true for the African American community, which has suffered not only a disproportionate number of Covid deaths, but also high-profile killings at the hands of police and White nationalists. Since the pandemic began in 2020, I’ve found myself particularly isolated because of an autoimmune illness, which has made leaving home especially risky and taken away my ability to travel internationally—an outlet I’d relied upon in the past whenever anti-Black racism had gotten to me.

When the lockdowns were at their worst, and Black death seemed everywhere, Hollywood didn’t offer much of a respite—shows and films like Lovecraft Country, Underground, and Antebellum still hit too close to home. Browsing on Netflix one night, I came across Chocolate, a Korean drama about a chef who falls in love with a neurosurgeon. As a child, the doctor dreamed of becoming a professional chef himself, and the two bond over their passion for cooking. At a time when Covid was raging unchecked across the country, this foreign-language tearjerker set in a hospice ward connected deeply with me, helping me to mourn the thousands dying every day. I was hooked. After that first taste, I dove deeply into the catalog of South Korean dramas now available on online streaming platforms. Since then, I’ve become a devoted fan.

In recent years, “K-dramas” have steadily gained a foothold among American audiences, riding a larger “Korean wave” of wildly popular K-pop musical groups like BTS and Blackpink and celebrated Korean filmmakers like Bong Joon-ho (director of the Academy Award-winning 2019 film Parasite). You can see this trend as yet another sign of globalization: the growing interconnectedness of the world’s markets and cultures. As singularly dominant as Hollywood has been over the past century, creators in other countries are increasingly able and eager to get their homegrown work shown widely in global media markets. The flow of blockbuster pop culture is no longer so one-way.

As someone tired of hearing the same stories from American shows and movies, I’ve found it refreshing to see Korean (and Nigerian and Brazilian) perspectives on TV. At the same time, the surging popularity of K-dramas has brought with it a host of concerns about representation and historical accuracy, as recent controversies underscore.

Kdramas have been a global phenomenon for years, with massive fanbases in societies as linguistically and culturally diverse as India, China, and the Philippines. A fledgling market for these shows finally emerged in the U.S. thanks to Dramafever, a popular streaming service that launched in 2009. After Dramafever shut down in 2018, Netflix helped popularize K-dramas among its increasingly global selection of titles. Then came Squid Game. The spectacular success of the 2021 survival drama—which became Netflix’s top-viewed program in 94 countries and remains its largest series launch—highlighted just how mainstream these Korean shows have become across cultures.

K-dramas tackle your typical genre fare—serial-killer crime procedurals, romantic comedies, soap operas, period dramas—usually across a sixteen-episode arc. However, the period dramas (sageuks) tend to focus on the Joseon era, the five centuries when Korea’s last dynasty ruled. And in the overly theatrical melodramas (makjangs), characters are inexplicably at risk of being hit in the face with fermented cabbage—as part of the trope known as the “kimchi-slap.”

While clearly there’s a lot of cultural context that non-Korean viewers will miss in these shows, I’ve found the stories easy to relate to. Perhaps it helps that I was raised by Nigerian immigrants; as a U.S.-born ada, or eldest daughter in an Igbo family, I see many similarities in the ways that the Korean characters on screen understand age as a status marker and observe rites to honor their ancestors, yet also uphold patriarchy through a preference for sons. I know how hard it is to fulfill your personal needs and desires when you’re part of a community that prioritizes the collective over the individual. And I can understand the great lengths that the characters in K-dramas go to save face—like them, I come from a culture where you always represent not just yourself, but your entire family and ancestry line.

With all the recent debates over cultural appropriation and representation in American entertainment, it’s also been fascinating to hear—thankfully, as a detached outsider—about the controversies that have raged around hit K-dramas. Sometimes, the furor has had a geopolitical dimension. China has unofficially banned K-dramas (along with K-pop bands and other Korean media) since 2016, when Seoul agreed to deploy a U.S.-made missile defense system that Beijing opposed. In turn, Korean audiences have lashed out whenever their TV shows have appeared to side with China in a larger nationalist debate over whether aspects of Korean culture originated across the Yellow Sea. For example, the 2021 K-drama Joseon Exorcist was canceled after only a few episodes due to controversies over its use of Chinese props and alleged historical inaccuracies. Another recent show, Mr. Queen, faced a backlash when its origins in a Chinese novel and web drama came to light. The outrage has been particularly intense whenever Chinese brands have tried to hawk their versions of traditional Korean dishes like bibimbap through the product placements rampant in many K-dramas.

Not surprisingly, the focus of some K-drama storylines has been the fractured relationship between North and South Korea, divided after a bloody civil war where the U.S. and China sat on opposing sides. The 2019–20 series Crash Landing on You follows a wealthy South Korean socialite who accidentally paraglides across the demilitarized zone and meets a North Korean army captain who helps her hide; romance ensues. A hit in South Korea that was subsequently picked up by Netflix, the show drew both praise and criticism for its sympathetic portrayal of North Koreans. (For their part, North Korean state media savaged the show’s creators as “human rubbish.”)

Earlier this year, Disney released the K-drama Snowdrop on its streaming service. Another series with a contentious take on North–South relations, Snowdrop takes place in 1987, a pivotal year in South Korea’s slow transition from dictatorship to democracy. Even before its release, Snowdrop was criticized for depicting a romance between a South Korean college student (played by K-pop idol Jisoo of Blackpink, in her TV debut) and a North Korean spy disguised as a graduate student. Critics pointed out that during this period of authoritarian rule in South Korea—shortly after democratic elections and a student uprising triggered a violent government crackdown—democracy activists were routinely labeled as North Korean spies and tortured. The show also seemed to imply that the return to democracy involved a compromise with North Korea, which critics said downplayed the important role that student activists played in clamoring for change. Another issue was the name of Jisoo’s character, Young-cho, which happened to be the name of a prominent activist in the real-life student movement.

A Korean civic association sued to put a halt to Snowdrop, and a petition asking the country’s president to intervene garnered over 300,000 signatures—not bad for a country of fifty million. In response to the criticism, the show’s producers reshot several episodes and changed the name of Jisoo’s character. Ultimately, a Seoul court threw out the court case, and Snowdrop continued airing on Korean TV, ending on a high note. Nevertheless, the controversy prompted Disney to postpone the show’s October worldwide release on its streaming service by several months.

Even as Korean producers have become savvy—perhaps too savvy—about how China perceives their content, they still have a lot to learn about what Western viewers find offensive or troubling. Recently, I was watching Twenty-Five Twenty-One, a K-drama about a romantically entangled group of friends, one of whom goes off to work as a television reporter in New York. To make a lighthearted reference to the main character spotting her love interest on TV, the show inexplicably used on-the-ground and reenacted footage of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, including disturbing images of people fleeing the area or lying injured in hospitals. A bubbly romantic comedy suddenly leapt off its tracks and veered into historical trauma, leaving me whiplashed and in tears.

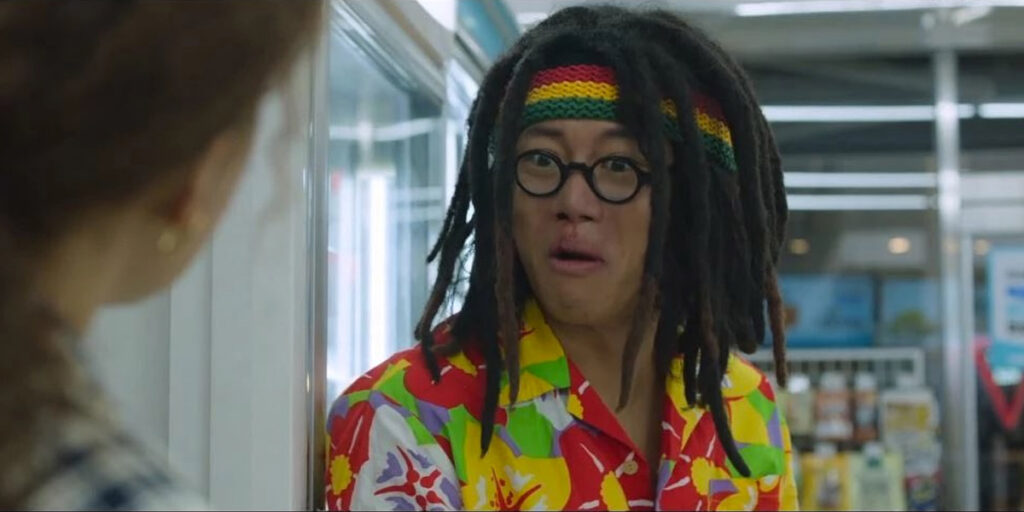

As much as I find watching Korean TV to be an escape from the fraught race relations in my own country, at times these issues have crept into K-dramas, too. The 2020 show Backstreet Rookie (a recent addition to Netflix’s catalog) was heavily criticized not only for depicting a high school girl in a sexualized way, but also for peddling in Jamaican stereotypes—namely, through a character who did not bathe and pulled an insect out of his fake dreadlocks. In 2021, the K-drama Penthouse sparked an online firestorm when one of its characters appeared in blackface. That unnecessary plot point was especially cringeworthy given that several of the show’s stars had just appeared in the United Nations #livetogether social media campaign against racism.

If sometimes I can be disappointed by the occasional moments of anti-Blackness and nativism in Korean media, at other times I feel heartened by how many Black women and other women of color are vocal fans on social media. After I started watching K-dramas, I started looking around for other people who wanted to talk about them, which eventually led me to a podcast hosted by three Brown women based in the U.S., the UK, and India: Dramas over Flowers, a nod to the iconic K-drama Boys over Flowers. I immediately took a liking to the hosts’ way of mixing together fangirling and critical analysis—the latter based on their many years of watching and writing about K-dramas. (Recently, co-host Anisa Khalifa appeared on the NPR show 1A to talk about the growing popularity of these shows.)

It turns out that women of color play key roles in online communities devoted to Korean media. For instance, one of the largest K-drama fan clubs is run by a group of women in the United States and Canada—most of whom happen to be Black. With over 12,000 followers on Clubhouse (an audio-based social media app), the K-Dramatics Club has hosted watch parties for hit dramas, held Q&As with people in the Korean entertainment industry, and created game shows to quiz members on K-drama trivia. Last year, the K-Dramatics received a shoutout in a Teen Vogue piece (along with their “sister” club, the K-Pop Kickback) for creating fandom spaces where people were free not just to gush over their favorite K-drama but also to discuss anti-Black stereotyping and other problematic material in Korean media.

If the content first lured me down the K-drama rabbit hole, the community has kept me coming back. During the lockdowns, the K-Dramatics Club regularly organized chat rooms on Clubhouse. On an otherwise dreary Christmas in 2020, Dramas over Flowers hosted a special Zoom session for their listeners. These communal events helped ease my loneliness during the bleakest moments of the pandemic.

A good story is a good story, no matter where it comes from, and I’m glad that today’s audiences are more open than ever to cross cultural boundaries for their content. It may have taken longer than other forms of globalization, but it seems that a growing share of the things we watch—much like the things we buy—now come from creators abroad. Yet there is an important distinction to be made here. By design, a foreign-made toaster or T-shirt doesn’t usually bear conspicuous marks of that other culture. That’s not the case for entertainment. K-dramas are distinctively Korean, and part of their allure for foreign fans is the escape they provide from our own country’s perspectives and problems. However, I hope that this influence can run both ways, and that the growth of diverse and international fandoms for these shows and movies inspires their overseas creators to feel a real sense of responsibility for the accuracy and sensitivity of their content. After all, the whole world is watching.

Republication allowed: This content has been published under a Creative Commons Attribution/No Derivatives license (CC BY-ND). You can republish it for free so long as you follow our guidelines.

Chinyere Osuji Chinyere Osuji is the author of Boundaries of Love: Interracial Marriage and the Meaning of Race, uses social science to understand how Blacks interact with ethnic and racial “others,” and has watched Something in the Rain five times. Site | Instagram | Twitter | Clubhouse

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content