The economic impact of market restrictions prompted by the pandemic—not to mention the coronavirus’s broader toll of more than 200,000 Americans deaths and other losses from ruined health and well-being—will likely linger well into the next president’s term. In the meantime, the pandemic appears to be accelerating trends toward greater income and wealth inequality within the country. U.S. billionaires have fared spectacularly well under the lockdown, having increased their wealth by $931 billion since March, according to data from Forbes analyzed by Chuck Collins and his collaborators. A report by the anti-poverty group Oxfam estimates that Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos now has so much money that he could pay each of his employees a six-figure bonus and still have more wealth than he had in March. Meanwhile, less advantaged Americans have been hit hard by the lingering downturn. Although stimulus checks and temporary expansions of unemployment benefits for a time worked well to mitigate the damage, poverty rates have recently spiked. Covid-19 cases, hospitalizations, and fatalities are disproportionately high among people of color. And while high-wage earners have recouped almost all their job losses, employment among low-wage earners remains almost a fifth lower than it was at the start of the pandemic, according to an analysis by Raj Chetty and other researchers.

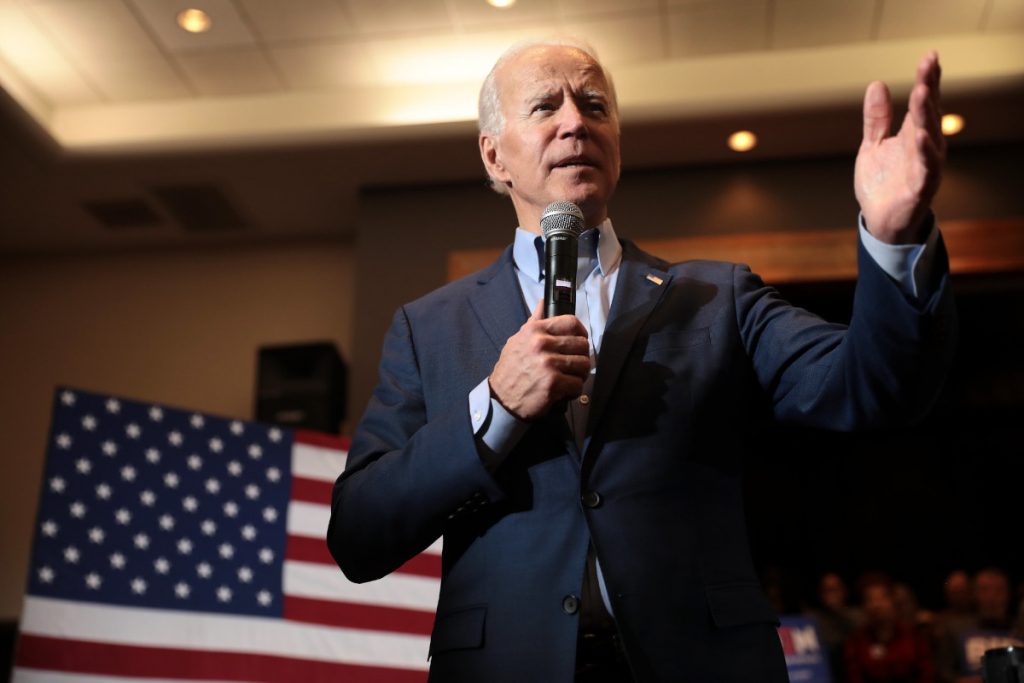

Amid this upheaval, the next president will make policy decisions with major implications for whether the gap between the rich and poor in this country grows or narrows. Joe Biden and Donald Trump have put forward two starkly different visions for the country’s economy—particularly in regards to tax policy, which will dramatically shape income and wealth inequality over the next decade. In general, Trump argues that the tax cuts on high earners that his administration pushed through in 2017 should be extended, which he believes will lead to greater economic growth. Biden supports rolling back tax cuts for those who earn more than $400,000, saying on the campaign trail that the wealthy need to pay their “fair share.” The continued impact of the coronavirus on the economy will complicate these policy decisions moving forward, but we can sketch out the sort of agenda each candidate will likely push forward once in office—based on their stated proposals as well as their track record while in office—and the possible impact of a Biden or Trump presidency on economic inequality.

First, it is important to note that income and wealth inequality have been growing almost without interruption since the 1980s, according to the World Inequality Database, a repository of data maintained by an international team of researchers. Since around 2012 the levels have stayed more or less steady, though the latest available figures do not account for the impact of the pandemic. For example, after taxes, the top 10 percent of earners took in 39.9 percent of all income in 2012—the end of Barack Obama’s (and Joe Biden’s) first term in the White House. That figure has stayed slightly below that level in the years since, landing at 39.0 percent in 2019, Trump’s third year in office. The richest tenth of Americans took in 73.9 percent of the country’s wealth in 2012, the highest level since World War II, but that share has also fallen slightly since. Granted, it can take years for shifts in policy to register on observed levels of economic inequality, and many trends that affect inequality—such as automation, education, and globalization—are massive tanker ships that heads of state can only turn by degrees, if at all. Nevertheless, the next president will be able to shape levels of inequality rather directly in two ways: through the repeal, or survival, of the tax cuts that the Trump administration passed in 2017, and through the administration’s response to the ongoing economic fallout of the pandemic.

While it lowered taxes across the income spectrum, the 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA) benefited the well-off much more in both absolute and proportional terms. In 2018, for example, a typical low-income household saved $40 and a typical middle-income household saved $800, while the top 1 percent of households—those making $733,000 or more—received an average tax cut of $33,000. Unless extended, these individual tax cuts will expire at the end of 2025, but the legislation’s large cuts to corporate taxes—which largely benefit wealthy households that own stock—are permanent. In its current form, the legislation is costing taxpayers $1.9 trillion in lost revenues over an eleven-year period, according to the Congressional Budget Office. A recent analysis by the Brookings Institution, a centrist think tank, concluded that—contrary to the claims of its supporters—the legislation failed to pay for itself by stimulating the economy.

Trump has stated that preserving the tax cuts would be a priority of his next administration. Biden plans to restore Obama-era tax rates on households that make more than $400,000 and limit how much high earners can deduct. His proposal to tax the capital gains and dividends of millionaires at the same rate as employment income would also have major implications for inequality, given that rich households make much of their money from stock, and yet often pay lower taxes than salary and wage earners on it. Biden also proposes to increase Social Security benefits for lower-income and older seniors, which will reduce poverty among the elderly, even as he rolls back some of the exclusions that have shielded higher incomes from Social Security taxes. Finally, Biden has proposed increasing the top corporate tax rate from 21 percent to 28 percent—still substantially lower than under the Obama administration, when the rate was 35 percent—and increasing minimum taxes on profits, especially foreign profits. If Biden’s tax proposals become law, government revenues will grow by $4 trillion over ten years, the Tax Policy Center estimates.

During the Democratic primary, Biden’s rivals criticized his actual commitment to taxing the rich, particularly after Bloomberg News reported that he told wealthy donors that “nothing will fundamentally change” were he to become president. However, one of those erstwhile rivals, California senator Kamala Harris, is now his running mate, and the Biden-Harris campaign now supports her proposal for a dramatic expansion of the earned-income tax credit, a wage subsidy for lower-income workers. Biden has also come out in support of making housing vouchers for low-income renters a funded entitlement, and is considering a Democratic plan to transform the federal child tax credit into a larger, unconditional child allowance—two measures that will greatly widen the circle of households that receive assistance under these programs. Columbia University researchers recently analyzed the potential impact of these three proposals and concluded that together they would cut the poverty rate by half, reduce the child poverty rate by three-quarters, and substantially narrow the racial and ethnic poverty gap.

Until the pandemic hit, the U.S. economy had been experiencing an unprecedented economic expansion across the Obama and Trump administrations. To the extent that economic growth increases the size of the overall pie, it may be more beneficial than redistribution in raising the well-being of ordinary Americans in absolute terms. Indeed, between 2017 and 2019 the poverty rate fell from 12.3 percent to 10.5 percent, according to census data. For his part, Trump predicts record-breaking growth in his next term (in the 2016 campaign, he promised 4 percent annual growth, which in reality has ranged from 2.3 to 2.9 percent between 2017 and 2019). Even if such growth rates could be attained, however, there is concern that income inequality has reached such extreme levels that headline indicators such as GDP growth—or, for that matter, stock market indices—do not adequately reflect the well-being of typical American households. In addition to redistribution through tax policies, then, more direct approaches to reduce inequality—such as labor regulations, targeted job creation, and debt relief—are needed.

When it comes to the employment policies, Biden supports a federal minimum wage of $15 an hour. During the 2016 campaign, Trump expressed support for a $10 minimum wage, while arguing that the states should really decide such policies (Larry Kudlow, director of the president’s National Economic Council, has argued the minimum wage should be zero). While Trump appointees in the National Labor Relations Board and the courts have moved to weaken labor unions and worker protections more broadly, Biden has pledged support of legislation to expand collective bargaining rights for workers and punish violations by employers. Given the role that a strong labor movement plays in reducing income inequality, the next administration’s relationship with organized labor will be decisive, and some labor leaders have expressed hopes that a Biden will institute the most pro-union administration in generations. Biden’s track record, however, is complicated in part by his support over the decades of the North American Free Trade Agreement, the normalization of trade relations with China, and other free trade agreements. In recent years, research has highlighted the major impacts that free trade—particularly with China—had on U.S. manufacturing firms, devastating working-class communities that relied on relatively well-paid factory jobs for those with less formal education. Trump renegotiated NAFTA with Canada and Mexico, with the agreement’s stronger worker protections (including changes to Mexican labor rules on union organizing) gaining the backing of Democratic lawmakers and labor groups. With less bipartisan support, Trump has made his tougher line on trade with China a centerpiece of his reelection campaign. Trump argues that his trade war will ultimately restore domestic manufacturing jobs; in the short term, it is levying substantial costs on American consumers.

Trump campaigned in 2016 on promises to invest in infrastructure, which would presumably have positive benefits for middle- and lower-income Americans, who would be in line for many of the jobs created. For much of his presidency, he has pushed for a $2 trillion infrastructure bill to rebuild crumbling roads and bridges and invest in future industries. Over the years his proposal has failed to get any traction, in part because Trump pulled out of negotiations with Democrats on the legislation, stating that a deal was not possible while Democrats continued to investigate him. Recently, the administration unveiled a smaller $1 trillion infrastructure plan, but it has stalled in the Senate due to Republican concerns over the debt. For his part, Biden has called for $2 trillion to be spent over his first term to create jobs in manufacturing and clean energy research, construct and modernize schools, and upgrade roads, bridges and highways. The proposal is intended to stimulate the economy and create jobs for ordinary Americans while adhering to Biden’s net-zero greenhouse gas emission target.

Another plank of Biden’s platform with major consequences for inequality is his proposal to forgive student debt. Americans currently owe more than $1.5 trillion in student loans, a figure that has risen fivefold over the last two decades to become the second-largest source of debt behind mortgages. Thanks to the passage of 2005 legislation widely supported by the financial industry—and by Senator Joe Biden—this particular debt cannot be absolved through bankruptcy. Millennials and Gen Zers have faced mounting tuition costs, and the loans taken out to finance their higher education wind up stunting their later financial progress, particularly for the children of working-class households. Biden has called for making two years of community college tuition-free and doubling the maximum value of Pell grants for lower- and middle-income students. To highlight racial economic inequality, his plan includes an additional $70 billion targeted to historically black colleges and universities.

Meanwhile, the fate of the Affordable Care Act under the next president will have major repercussions for lower-income Americans, who benefit especially from the expanded Medicaid access provided by the law. After the passage of the Affordable Care Act, the percentage of uninsured Americans fell. Trump has acted in various ways to subvert the law, and the number of uninsured has risen under his presidency, from 8.6 percent in 2016 to 9.2 percent in 2019. The nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget has estimated that the health care plan that Trump supports as a replacement for the Affordable Care Act would raise the number of uninsured by an additional 21 million, or about 7 percentage points, and increase health care costs by $330 billion over ten years.

The Biden campaign claims that its health plan would extend health care to an estimated 15 to 20 million people, half the total of Americans currently uninsured. Among other things, it would lower the age for Medicare eligibility by five years and offer all Americans a public option for insurance. Given the offsets from lowered drug costs and higher taxes, the Biden health care plan could potentially save Americans money in a best-case scenario, according to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, but will more likely end up costing roughly $850 billion.

Regarding the nation’s debt, a strict look at receipts and outlays, provided by the Office of Management and Budget, shows that the Obama administration increased debt by $7.7 trillion over eight years, which includes the 2009 economic stimulus package and the variety of other interventions the administration pursued to stave off the Great Recession. Through the first term of the Trump administration, debt increased by $3.6 trillion, not including the $3 trillion in Covid-19 stimulus legislation passed so far. The danger of the current level of debt—$27 trillion, or $81,800 per citizen—is not so straightforward, however. Economists tend to reject the layperson’s view that a government taking on debt is equivalent to a household taking on debt; in fact, one school of thought associated with the Obama administration—modern monetary theory—makes the case that government debt at current levels is a sign of a healthy national economy, which foreign investors want to have a stake in, and which grants the federal government access to relatively low-cost loans to fund its expenditures. That said, those close to Biden have characterized him as wanting to restrain spending in light of the recent growth in the federal deficit.

In the short term, however, both Trump and Biden seem willing to spend emergency funds to help the many Americans out of work because of the pandemic. Roughly twenty-five million Americans now collect some form of unemployment benefits, and racial differences in unemployment remain stark. Because of the many Americans still left out of the recent improvements in the economy, some commentators have taken to calling the recovery “K-shaped”—with separate trend lines for the country’s wealthier and poorer citizens. Those out of work tend to have service jobs that cannot be done from home, while well-paid office professionals have more easily transitioned into teleworking. Meanwhile, Main Street businesses have taken a beating, with data from the review app Yelp suggesting that 60 percent of businesses that have closed since the pandemic began have shuttered permanently.

The $2 trillion put to use by the CARES Act did provide a substantial amount of relief to ordinary Americans in the months after it passed—among them, one-time stimulus checks, temporary expansions to unemployment benefits, and forgivable loans to small businesses that continued to pay their workers. (Granted, the CARES legislation also offered relief for the wealthy, given the ways that large corporate chains were able to take advantage of the small-business loan program, and thanks to provisions that Republican lawmakers inserted to cap real-estate losses and offer other tax benefits that disproportionately benefited the ultra-wealthy.) This massive infusion of government funds kept nearly ten million Americans out of poverty, according to the Urban Institute, and meant that the poverty rate actually continued to decline into April, May, and June, bottoming out at 9.4 percent. However, the expiration of the legislation’s $600 weekly federal supplement for unemployment benefits in July has been followed by a spike in poverty and an uptick in new unemployment claims, which remain higher on a weekly basis than during the peak of the Great Recession. President Trump has repurposed federal funds to make up for some of the lost supplement—though not all states have accepted the money, and many of those that did have yet to distribute it. His administration has also extended federal moratoriums on evictions and student loan payments to the end of the year.

At the moment, Democrats and Republicans continue to negotiate over another stimulus package. Congressional Democrats and Trump have both argued on behalf of a larger stimulus, but Senate Republicans have blocked such measures, arguing that they are unneeded and that the impact on the deficit would be too great. There is still a chance for a last-minute deal, but the broader shape of U.S. inequality will likely be determined in the next president’s term—above all, in what is sure to be a bitter fight over tax policy and continued assistance for the many Americans who will likely still be left out of any recovery.

This essay was coauthored by Timothy Beryl Bland and Victor Tan Chen and cross-published in Virginia Commonwealth University’s Election 2020 blog.

Timothy Beryl Bland Timothy Beryl Bland, PhD, is a writer based in Richmond. For his doctorate in public policy and administration from Virginia Commonwealth University, he researched the influence of think tanks.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content