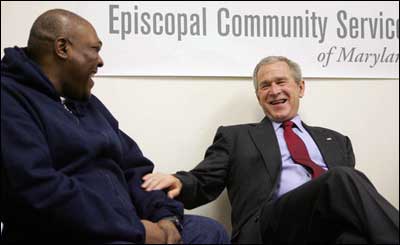

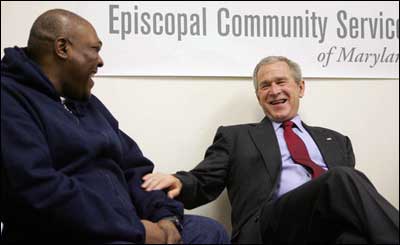

In the basement of a row house in East Baltimore, Maryland, Adolphus Moseley, who had served time in jail for cocaine possession, was listening to a visitor who had been arrested decades earlier for drunken driving.

“I understand addiction,” George W. Bush was saying, according to a reporter allowed to overhear the conversation, “and I understand how a changed heart can help you deal with addiction.”

President Bush was talking about himself, of course. In the last year of his presidency, he seems to have become more candid about a problem with alcohol that he has often talked about more vaguely in the past: He had quit drinking at the age of 40, and has attributed his continuing sobriety to vigorous exercise, and religious faith.

But the president was in Baltimore for what he might call a higher purpose. He was visiting the Jericho Program, which works to help recently released prisoners succeed outside of prison. Jericho is run by Episcopal Community Services of Maryland, one of some 5,000 religiously oriented groups throughout the United States that, during the Bush administration, have received funds from the federal government to provide various social services.

The day before, in his final State of the Union address, Bush had trumpeted what he had intended from the start of his presidency seven years earlier to be a key part of his domestic agenda, his so-called faith-based initiative.

His visit to Baltimore, like his faith-based initiative itself, may not have gone completely as planned. When Moseley suggested that the city could use more programs like Jericho, Bush replied: “There are programs like that all over the city. They are called churches.”

“They are not sincere, like Jericho,” Moseley said.

The president seemed taken aback, according to press reports. “My only point to you is there are a lot of faith-based organizations that exist to help deal with very difficult problems,” Bush said. “It starts with the notion that there is a higher power that will help people change their thinking.”

Mixed legacy

For the past seven years, Bush has hoped to change the thinking of America about the involvement of the state in church activities. But many observers see at best a mixed legacy.

Some who support Bush’s goals say that they have not been fulfilled, or point to inequities: One report showed that federal funding awarded to black churches is disproportionately low.

But opponents question the whole concept, accusing the president, in the words of a recent editorial in The New York Times, of having “worked to blur the line between church and state.”

It is not just the achievements of his faith-based initiative, but its very definition, that is also in something of a haze.

By the way that President Bush talks about programs such as Jericho, it would be easy to infer that it is their religious orientation that makes them effective. But studies are inconclusive about the degree to which faith-based organizations are any more effective at providing social services than secular ones. And — to pick the program that Bush chose to highlight — Bonnie Ariano, Jericho’s director, says that there is no religious content to their program.

“Sometimes a client will ask to say a prayer,” Ariano says, “and we will ask the other clients if that is okay with them.” The role that faith plays in the program is in motivating the organization to work with the poor.

Indeed, anything more would be unconstitutional. The U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that federal money cannot be used to fund religious worship, religious instruction, or any kind of religious proselytizing, since these activities would violate one of the core principles upon which the nation was founded: the separation of church and state.

It is this principle that critics of varying beliefs see endangered by Bush’s faith-based initiative. Some worry that the government could wind up funding religious ideology. Others are concerned that the government money could interfere with religious activity. Still others are most disturbed by the fact that the religious institutions getting federal funding are exempt from many federal civil rights and labor laws.

Faith and the feds

Government involvement with religious organizations did not begin with the Bush administration. During the Great Depression, government looked to religious groups to help address the social ills of that era. Many years later, Congress and President Bill Clinton once again turned to those of faith. During Clinton’s second term, the Charitable Choice laws were passed, which clarified the rights and responsibilities of faith-based organizations receiving funds for certain social service programs.

Bush campaigned to bring these organizations further into the federal fold on his way to the White House. Once elected, he signed a number of executive orders. One stated that faith-based organizations should get an equal chance at receiving federal dollars, and the other created the White House Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives.

In 2006, $2.2 billion dollars was awarded to faith-based organizations to aid such needy constituents as the homeless, at-risk youth, recovering addicts, returning offenders, and people with AIDS. The number, according to the White House, represents a 41 percent increase over 2003, although some have disputed this figure.

The Criticisms

1. Proselytizing

Critics charge that religious views have dictated the policies and practices of a range of federally funded programs.

Many of the pregnancy resource centers funded by Bush’s initiative were found to be providing false or misleading information about abortion, according to a 2007 report by the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. Callers to the center were told that “having an abortion could increase the risk of breast cancer, result in sterility, and lead to suicide and ‘post-abortion stress disorder.’”

“Abstinence-only” and other religiously inspired views reportedly led to the cessation of funds awarded to nongovernmental agencies in developing countries to provide condoms or to educate people about their use.

Department of Justice officials in charge of a program that funds faith-based organizations that run halfway houses told investigators they assumed these groups were exempted from the religious activities ban if chaplains or “organizations assisting chaplains” were involved. But this stance “could be read as allowing all providers of social services in these settings to engage in worship, religious instruction, or [proselytizing],” regardless of whether the religious activities are voluntary on the part of the participant, according to a report in 2006 by the General Accountability Office, an official government watchdog.

2. Inequity

One research group has found that the money distributed by the Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives has not been awarded evenly among religious groups.

Only 2.5 percent of black churches have received funding from Bush’s faith-based initiative, a survey by the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies showed.

“The administration has not been successful in informing the black ministers about the nature of the program,” David Bositis, senior political analyst for the Joint Center told Black Enterprise.

3. Politics over faith

Even while Bush is criticized for pushing the government’s relationship with religious groups too far, others allege he has acted as if he has done more than reality would bear out.

David Kuo, who was the second-in-command at the Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives, has accused Bush of manipulating religion for political gain. Most recently, he coauthored an op-ed in The New York Times excoriating Bush for not doing enough. “Every nonpartisan study has concluded that the initiative has not delivered the grants, vouchers, tax incentives, and other support for faith-based organizations that the president originally promised,” the piece said.

The rise in funding to faith-based groups announced by White House was indeed misleading, according to a piece in The American Prospect. The article says the administration juggled the numbers to make it look like a rise. It points out that certain agencies were already distributing grants to these groups, but had not been part of the original tally.

4. Special arrangements

The government may be doing more than offering funds to religious groups. Since 1989, Congress provided hundreds of special arrangements, protections, or exemptions for religious groups, according to a two-part series in The New York Times in 2006. The story points out that these advantages give religious groups an edge in the competition to provide social services, whether they are government-funded or not.

A number of states have also exempted religious child-care programs from certain oversight, including Texas under Bush’s tenure as governor. There, religious groups were exempted from the need to license their programs under legislation pushed through by Bush. Although few groups took advantage of the new law, at the facilities that did, abuse of the law was 10 times more likely to occur, according to a study by a local watchdog group. The state no longer exempts religious groups from licensing.

5. Undermining religious independence

Ironically, even many of the potential recipients of these grants are worried about their effect.

A letter signed by a 1,000 religious leaders representing a wide range of beliefs stated that they are concerned the funds would encroach upon their activities: “The flow of government dollars and the accountability for how those funds are used will inevitably undermine the independence and integrity of houses of worship.”

As Rev. Ted Fuson, pastor of the Culpeper Baptist Church, told the Jewish World Review: “The folks that send the money tend to tell you what to do with it and rightfully so, if you are taking tax dollars.”

The future

Will the faith-based initiative end with the Bush administration?

The answer is unclear. According to Christianity Today, all remaining presidential candidates have “voiced support for federal funding of faith-based social services. So far, however, none has unveiled a specific plan for the White House’s Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives.”

Meanwhile, the concept has spread beyond the federal government. More than 100 mayors and 35 governors now have faith-based offices.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content