It’s a small coffee shop, a Shingle-style shack with blue trim, listed by Yelp as one of Laguna Beach’s best. Cookies and biscotti lie in a basket in front of the order window. The barista, an upbeat blonde woman in her late fifties, early sixties, comes over to me. As I’m trying to choose what flavor to put in my coffee, we start talking. She finds out I’m from Phoenix and asks what brought me to Laguna.

It’s a small coffee shop, a Shingle-style shack with blue trim, listed by Yelp as one of Laguna Beach’s best. Cookies and biscotti lie in a basket in front of the order window. The barista, an upbeat blonde woman in her late fifties, early sixties, comes over to me. As I’m trying to choose what flavor to put in my coffee, we start talking. She finds out I’m from Phoenix and asks what brought me to Laguna.

“My friend passed away two weeks ago. I’m here to clear my head,” I tell her. Hal, a pastor, was one of the first friends I’d made after moving to Phoenix a year and a half ago with my fiancé. He had helped us through some tough times.

She’s curious about where my accent is from. I tell her I was born in Iran. “But I have lived here longer than I have lived there,” I quickly add.

It’s a cool, sunny November morning. As she’s making my coffee, the woman spots the book I’m carrying in my hand, The Ministry of Guidance Invites You to Not Stay, by Hooman Majd. She asks me what it’s about. I tell her it was written by an Iranian immigrant who had left Iran when he was eight months old. When he turned fifty, he decided to go looking for his grandmother’s house halfway around the world, hoping to find his roots. He found the area, the familiar scents, the leftover mud walls. But he couldn’t find the actual house.

His story is not much different from mine, I say. Several years ago, I visited the neighborhood where my family used to live in Tehran. For the first time in more than two decades, I walked our old block, looking for the home I had grown up in. But it wasn’t there anymore.

Describing my trip to Iran reminds me of a passage I read in Majd’s book: Maybe it was better that the house and even the street weren’t there. Reality could not possibly rival a childhood memory, and my memory was intact, if rose-colored. Not finding the house also kept me somewhat rootless—now there truly was nothing for me to directly claim as mine.

“My grandparents emigrated from Denmark,” the woman tells me. She starts talking about how her grandparents worked hard, how they worked their way up—until one day they owned their own business.

I expect her to go on about her family, yet she abruptly turns the conversation elsewhere. “I don’t see my culture here anymore,” she says, testily. At first, I think she’s talking about Danish culture. But I’m mistaken. “Have you been to Heisler Park?” she asks me.

“No.” I know from my friends in Laguna that Heisler is the park Iranians go to for their New Year celebrations.

“When I went to Heisler Park, I had to pass all these Asian tents to be able to celebrate my Memorial Day. Before the Asians, it used to be Mexicans.”

There’s an awkward pause. I’m not sure how to respond. “You know what?” I finally say. “It’s too cold to sit outside. I’ll come back later.”

As I turn away, I feel disappointed with myself for not saying what’s really on my mind. I want to tell her that she should have compassion for those who leave their countries to come here. I want to remind her that her ancestors were also immigrants. But I don’t have the courage to speak up.

Instead, I walk away, thinking about what I should have said, feeling like the outsider I still imagine myself to be—twenty-seven years after coming to America.

• • •

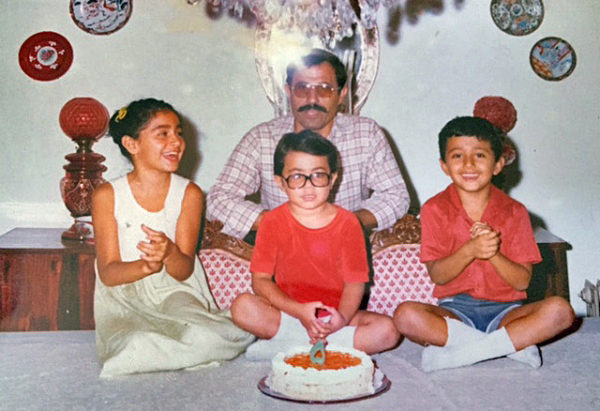

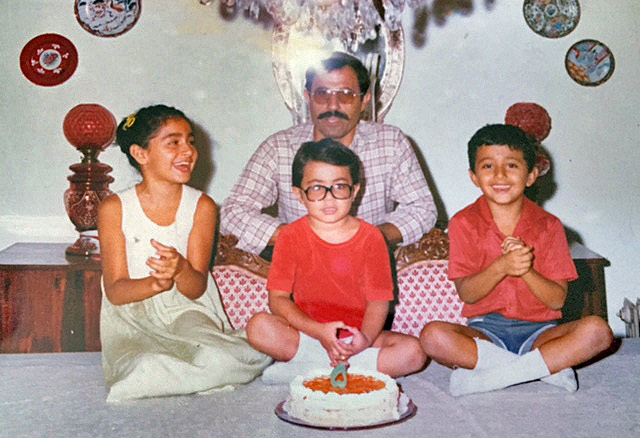

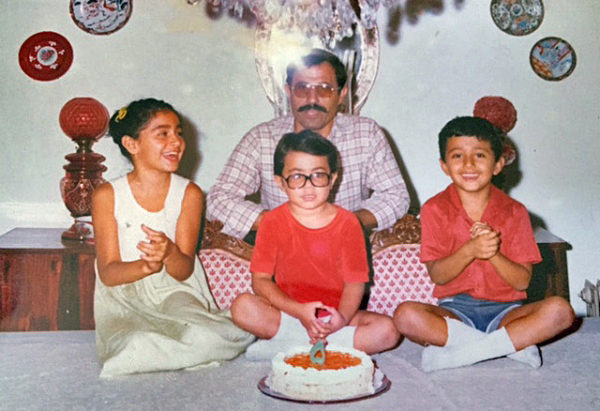

I was born in Tehran. When I was seventeen, my family decided to leave Iran. We immigrated to America not because of conflict—the Iran–Iraq War had already ended by then—but for opportunity. My father was an engineer, and my mother had studied law before becoming a stay-at-home mom. They wanted their children to have a good education.

Growing up in Houston in the nineties, I fought with my mom because I didn’t want her to pack Persian food in my lunchbox. The salt-laden Lunchables would do—anything to fit in among my new classmates. During lunch breaks, I used to hide in the piano rooms to avoid the humiliation of not speaking English. At home, I practiced pronouncing words properly, without the thick Iranian accent. “The,” not “de”—so what if we didn’t use the sound th in Farsi? We were living in America. We needed to respect its language.

As I grew older, I distanced myself from the Iranian community and embraced American culture. Though I was born a Muslim, most of my family and friends had lost interest and trust in religion, thanks to Iran’s Islamic Republic. From early on, I had steered clear of mosques. Yet in America, whenever friends invited me to church, I went. Defying my parents and their Iranian values, I dated American boys without plans to marry. Once, my mom—playing matchmaker—asked me to meet her friend’s son, who had traveled from Switzerland to see me. I refused to go.

When it came to school, however, my two brothers and I were good Iranian children. My father, who had gone from building factories to manufacturing blinds, had no time for nonsense, and demanded hard work and excellence in whatever we did. He was the type of immigrant dad who, if I got a 98 on a test, would ask me, “Who got the 100?” Once the managing director of an engineering firm in Iran, he had been forced to take a job as a low-level supervisor at the blinds plant when we moved to America. He expected much more for us, and his high expectations paid off: two of us earned doctorates, and the third, an MBA.

At dental school, I’d been one of a large number of immigrants in my class. Being around people who shared my experience as a newcomer had been good for me, and by the time I graduated I was no longer as anxious about sticking out as an Iranian. After I finished school, I started an oral and maxillofacial surgery residency at a hospital in New Jersey.

I was in my second year there when the September 11 terrorist attacks happened. A few days afterward, a group of us were in the operating-room holding area waiting for a patient. News streamed on a small television set. We congregated around it, watching footage of the collapse of the Twin Towers over and over.

Soon the anesthesiologist and nurses were peppering me with questions about why the terrorists had done this. “You are from the Middle East, aren’t you?” someone asked me.

For years, every time I traveled by air, I was pulled out of the line for a “random search”—something my then-husband, also Iranian, avoided because of his light complexion.

After my hospital residency, we settled down in Atkinson, a tiny New Hampshire town along the Massachusetts border, and I became a US citizen. When I was finally able to vote in 2008, I felt such a sense of joy as I waited at the polling station to cast my ballot—only to have that feeling vanish when I overheard someone in line say, “We oughta show these towelheads who’s the boss.”

Let it go, I told myself. Why bother about what a couple of people in a small town think?

• • •

In Iran, we grieve the loss of a loved one for forty days, with ceremonies on the third, seventh, and fortieth days. We even have specific foods for funerals—halva, a sweet dish made with flour, butter, sugar, and rosewater and decorated with pistachios, is often served to mourners with tea.

In America, a culture of positivity, I don’t really know how to mourn. Right after Hal died, I disconnected from my emotions. Eventually, I became angry—at others for their platitudes, and with myself for how long it was taking me to get over his death. I needed to get away from it all, and so I went to Laguna Beach, where many of my old Iranian friends live.

I tell them how much Hal’s death has shaken me—and how much I’ve struggled to properly grieve for him. I need the ceremonies we used to practice, I tell them. I crave the taste of halva with tea.

They listen. Ironically, out of all my Iranian friends, the one who has the least nostalgia about her former life best understands the pain of that old wound. “You know, our parents are Iranian,” she says. “Our children are American. We, I’m afraid, are neither. We are orphans.”

I think back to my search for my childhood home in Tehran. I remember coming to the block where my family’s house had once stood, and seeing the sterile apartment complex they had built in its place. Good, I told myself. Who has the energy to feel emotional?

Afterward, a friend drove me around the neighborhood. We passed my middle school. The old mosque. The pastry shop I used to stop by on my way to school.

Suddenly, tears started streaming down my cheeks.

It wasn’t there anymore. It wasn’t there.

Bahar Anooshahr is an Iranian American writer and recovering oral and maxillofacial surgeon. Twitter: @banooshahr

Dear Reader,

In The Fray is a nonprofit staffed by volunteers. If you liked this piece, could you

please donate $10? If you want to help, you can also:

It’s a small coffee shop, a Shingle-style shack with blue trim, listed by Yelp as one of Laguna Beach’s best. Cookies and biscotti lie in a basket in front of the order window. The barista, an upbeat blonde woman in her late fifties, early sixties, comes over to me. As I’m trying to choose what flavor to put in my coffee, we start talking. She finds out I’m from Phoenix and asks what brought me to Laguna.

It’s a small coffee shop, a Shingle-style shack with blue trim, listed by Yelp as one of Laguna Beach’s best. Cookies and biscotti lie in a basket in front of the order window. The barista, an upbeat blonde woman in her late fifties, early sixties, comes over to me. As I’m trying to choose what flavor to put in my coffee, we start talking. She finds out I’m from Phoenix and asks what brought me to Laguna.