In this special edition of InTheFray, we focus on the interplay between religion and politics, especially during the singular and sometimes downright peculiar events of Campaign 2008, but we also go beyond U.S. presidential politics.

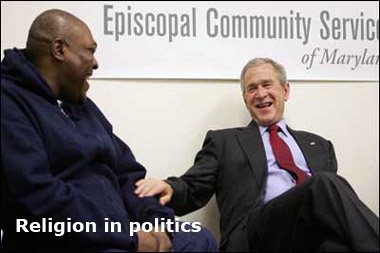

The complete line-up is to your right. Some stories offer a history of church/state issues in the United States. Others explain the consequences of recent developments, such as the look at the unhappy track record of President George W. Bush’s faith-based initiatives in Spreading the faith — and the funds. Some of this month’s articles report on conflicts between religion and politics abroad in places like Afghanistan. Others look inward, such as ITF senior editor Anja Tranovich’s interview with gay evangelical Rev. Mel White and Dr. Farnad Darnell’s personal essay on being Muslim/Mormon.

The question that inspired this edition — “Is there a ‘religious test’ in politics?” — was addressed two centuries ago in the U.S. Constitution, which specifically bans such a test “as a qualification to any office or public trust under the United States.” But in a broader sense, Americans have been struggling all along with this question in many ways. (See ITF Executive Director Victor Tan Chen’s time line highlighting more than 300 years of battles between "church and state")

Has religious conviction become a de facto requirement for presidential candidates in the half-century since the election of John F. Kennedy as the nation’s first (and so far only) Catholic president?

“I believe in an America where religious intolerance will someday end,” Kennedy said in his famous speech on religion in 1960, “… where every man has the same right to attend or not to attend the church of his choice, where there is no Catholic vote, no anti-Catholic vote, no bloc voting of any kind …”

Kennedy delivered that speech out of fear that his religion would deter many Americans from voting for him. In 2008, another presidential candidate, Mitt Romney, delivered a speech about religion and politics that consciously evoked the JFK address. Like Kennedy, Romney feared that Americans would not vote for him because of his religion, which in Romney’s case is Mormon. But some critics suggested the core of Romney’s argument was the exact opposite of Kennedy’s — intolerance of the irreligious rather than religious tolerance. “Freedom requires religion,” Romney said, “just as religion requires freedom.” (See more on Romney — including a fascinating contrast with his father George — in our interview with Randall Balmer, author of God In The White House.)

But the speech that has earned more comparisons with Kennedy’s during this campaign season was delivered by Barack Obama. Though Obama’s speech focused on race, it was brought about by religion: The speech was Obama’s response to attacks on his former pastor’s sermons. (Mark Winston Griffith comments on Obama’s speech in the context of politics and the black church in “The black church arrives on America’s doorstep.”)

For all this attention, Campaign 2008 does not seem to have clarified the issue of the role of religion in politics — or that of politics in religion.

“This political season has only heightened the confusion over the future of religion in the nation’s culture and politics,” Walter Russell Mead wrote in the March 2008 edition of the Atlantic Monthly, one of several publications to devote recent editions to the subject of religion.

Now InTheFray enters … into the fray. And so can you — add your answer to our round-up of views on whether there is a religious test in politics. Then take OUR religious test in politics, our quiz, and see if you know which 2008 presidential candidate said, “When discussing faith and politics, we should honor the ‘candid’ in candidate — I have much more respect for an honest atheist than a disingenuous believer.”

The answer — along with much in this edition — may surprise you.

Jonathan Mandell

Guest Editor

New York

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content