I’ve been walking down the streets of Cairo for weeks now, but I’ve never been to a corner. A map of the city’s geography slowly surfaces in my imagination, peopled with various urban landmarks. But in my vision of Cairo, the corners are nowhere to be found.

There are, of course, places where the sides of a block meet at an angle. In other cities, however, corners parse and define elements of urban space, reminders that there is a manufactured grid underlying the people and pavement. In my native New York, corners help orient a civilization that can no longer locate itself with respect to the stars. But here, corners are an afterthought. Edges and angles ebb and flow in a dance between spaces and crowds, like air pockets in clay — incidental to a social thicket that defies any preconceived scheme.

Here, corners are not actually extinct, but rather are like an obsolete tailbone. The newer outlying neighborhoods, where wealthier Cairenes reside, do mimic the clean edges of “developed” metropolises around the world. And the major commercial thoroughfares do fit into roughly perpendicular lines. Still, the Cairo I see, where pedestrians and vehicles blur in the frenetic, dust-caked streets, is fueled by a gnarled urban core that has little use for the conventional corner.

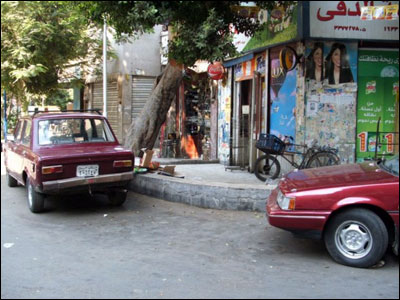

Here, spasmodic traffic neither follows rules nor needs them. Carts of cactus and melon butt against crookedly parked fiats. Clouds of lush trees erupt from scorched ground over an architectural jumble of postwar-socialist concrete slabs, high-rises, and European-style townhouses.

Cairo has plenty of squares — plazas known as midans, which are loftily titled after heroes, or “liberation” (tahrir), or the Sphinx. But these spaces are far from the manicured quadrilaterals characteristic of Western cities. To reserve a corner in the chaos just for hailing a cab or meeting a friend would seem an utter waste.

In the Dokki district where I live, when crumbling sidewalks kiss their cross streets, they typically curl narrowly around the foot of a cement stack of apartments. The “corner” might be colonized by a tree jutting from the concrete, or pensive men — maybe cabbies, maybe poets — sitting and puffing shisha from standing metal pipes. Pedestrians find it easier to share the adjacent asphalt with taxis and donkeys.

Cairo’s layout evokes the lyrical cursive of the Arabic script. Walls, alleys, and other spaces are distinct facets in the landscape, but they sometimes weave into each other, matted and coiling. Even the bricks seem somewhat elastic; the architectural contours rearrange themselves mischievously when you’re not looking to make you lose your way.

When you expect to turn a corner, you happen upon a roundabout, where traffic spools into a haphazard knot encircled by storefronts and cracked cement. Or a twist in your path zigzags into a bazaar of Orientalist clichés, like the Khan Al-Khalili suq, where hawkers haggle with tourists over brass lamps, papyrus posters, and other contemporary relics.

Follow another strip and find it suddenly swallowed by the entryway of a brightly lit mosque, where legions of beat-up shoes stand guard. Inside, socks and foreheads softly touch the carpet, and men check their cell phone messages amid an arabesque of delicate shadows.

In the Zamalek district on Cairo’s central island, artists have spun a would-be dead-end into a buoy of cultural happenings. At the terminus of 26th of July Street — named for the day Egypt took over the Suez Canal — the Culture Wheel harbors concert halls, lecture rooms, and photo galleries. On one side of the venue, beneath chugging traffic, a tiled pavilion flanking the murky belt of the Nile offers refuge to wistful minds.

Despite its physical anarchy, the city falls reflexively into a structured rhythm. Every day is punctuated by five moaning calls to prayer that swell up through the loudspeakers of mosques in simultaneity. For a few minutes, all of Cairo sings with the same tension, aligning the churning crowds into one spiritual refrain.

While the lack of straight lines and angles can feel liberating, it can stifle an outsider. Sometimes each turn reminds me of my alien status as passersby jeer in Arabic and stare. The sharpest corner I’ve encountered, perhaps, is the one that my foreignness backs me into, though I know I will escape by retracing my path back to the order and predictability of America.

But Cairo’s fluid landscape has always enough give to absorb outside elements. The Persians, Romans, and modern imperialists of every sort have occupied the city in turns. The sheer weight of its past collapses borders, mashing together churches and mosques and skin tones of every shade.

In a region percolating with war and paranoia, Cairo spins in relative peace on its own axis, slippery with honey and grease, and the sweat under headscarves and three-piece suits.

You don’t have to be here long to sense the odd joy — hushed but proud, a reason for the city to resonate praise to God each day. Without corners, it’s hard for me to grasp this place and how it plods on with such flair. But I’d rather that Cairo keep its secrets to itself and roll on as it always has, slipping through history’s fingers.

Sherif Megid is a Cairo-based photographer, filmmaker and writer of short stories. His works are inspired by the history and images of the street where he grew up, Sharaa El Khalifa in Islamic Cairo. He has published two collections of short stories and recently held an acclaimed exhibition of his street photography in Cairo.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content