Every so often I will drive by farmworkers toiling in the fields near my home in Davis, a town in rural Yolo County, California. Even in the middle of the summer, everyone will be covered from head to toe in long-sleeved shirts, khaki work pants or blue jeans, wide-brimmed hats, and work boots. It’s always a colorful scene. Cars of different shades, glinting in the sun, lined up along the dirt road running past the field. The faded reds, greens, blues, and browns of old work clothes. Rows of green crops, sunshine pouring down from a powdery blue sky, a line of rolling brown hills on the horizon.

When I saw several months ago that the Yolo Food Bank was looking for volunteers to do some harvesting, I signed up. I respected the work the food bank did, and I was curious about what went on in the fields of California’s Central Valley. In the back of my mind, too, were articles I’d read about how very few native-born Americans signed up to do farm work nowadays—and how those who did would quit right away. The articles would make shocking claims: Just a handful of the hundreds of Americans who apply for farm jobs in North Carolina last the season. A California grape farmer raised his average wage to $20 an hour, but his U.S.-born workers kept quitting: “We’ve never had one come back after lunch.” An Alabama tomato farmer said that in twenty-five years of farming, he could “count on my hand the number of Americans that stuck.” Was it true that migrant laborers were taking jobs that locals could be doing? Or was the work just too hard to attract Americans raised in relative privilege? I wanted to see for myself what harvesting was like.

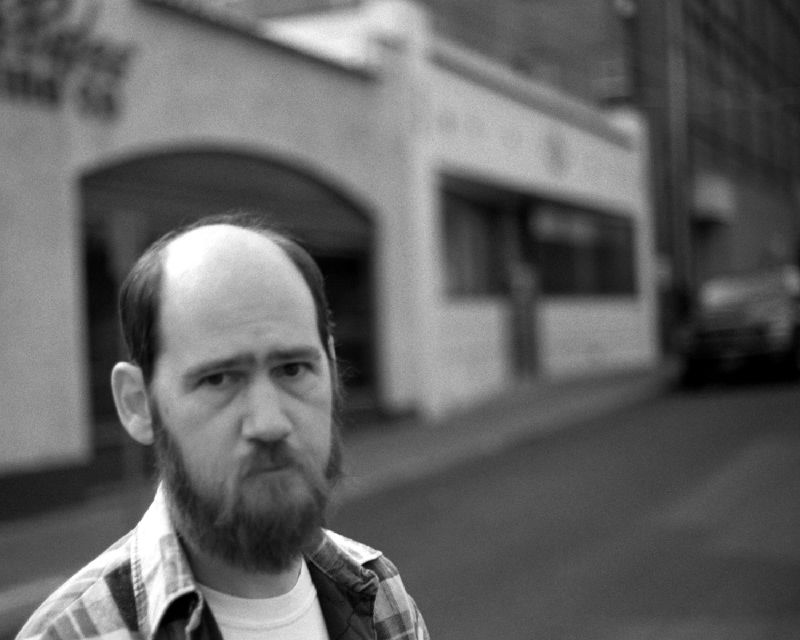

Continue reading High-Hanging FruitPaul Michelson Paul Michelson lives and writes in Davis, California.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

I’ve

I’ve