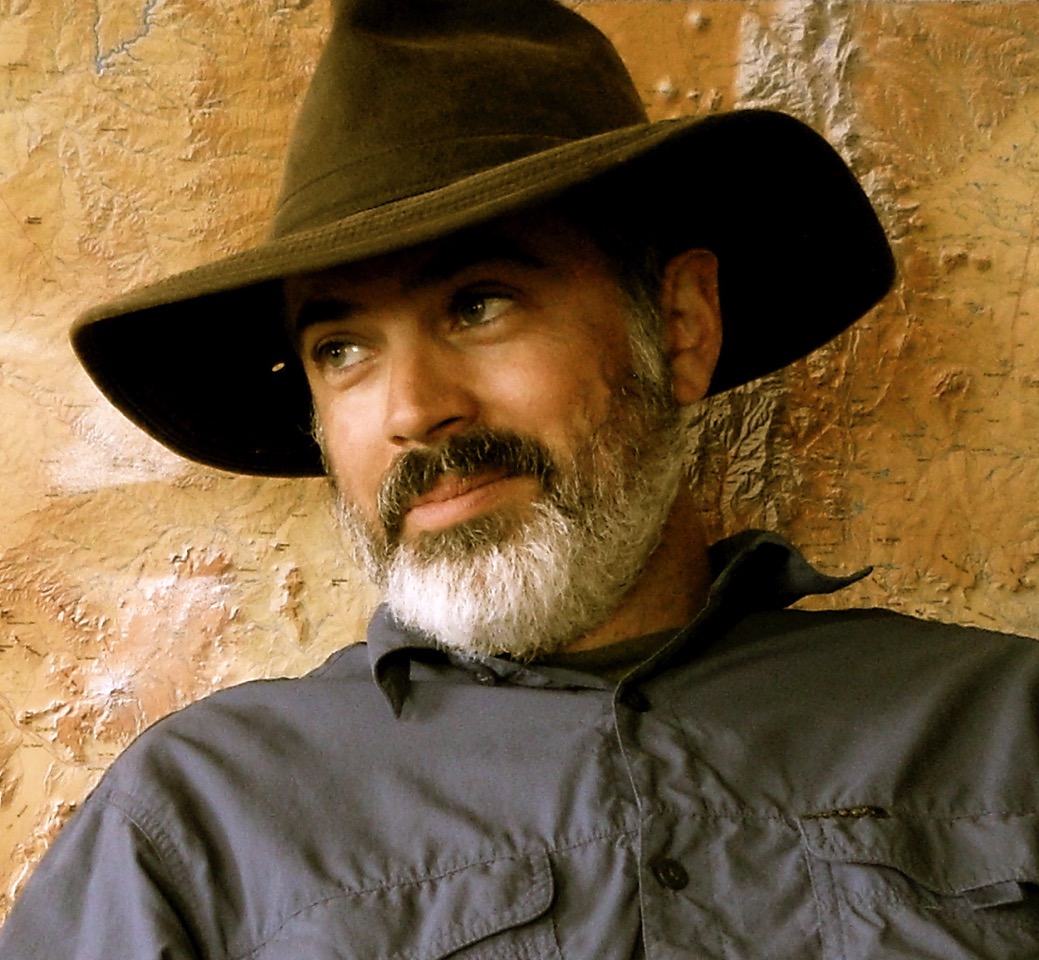

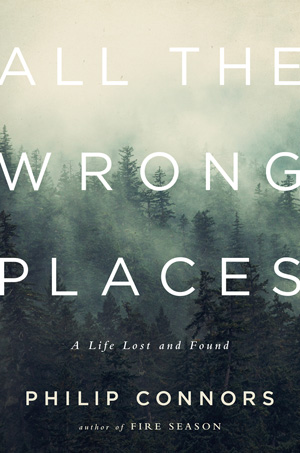

Earlier this year, forest-fire lookout and nonfiction writer Philip Connors came out with his second book, All the Wrong Places: A Life Lost and Found. It’s a beautifully wrought memoir about his brother’s suicide, which happened when Connors was only twenty-three. In the Fray’s Susan Dunlap talked with Connors over email in the spring about the way his brother Dan’s death shaped the trajectory of his own life, the approach he took to writing about a taboo subject, and the comforts of solitude.

You started out as a journalist and avoided getting an MFA degree. Were you daunted when you first set out as a creative nonfiction writer?

I first started writing nonfiction because I tried and failed to write quality fiction. A good deal of my apprenticeship—aside from working for newspapers—involved writing terrible short stories that no one has ever read, nor ever will. I just couldn’t write a good one. I couldn’t seem to finish a story without getting bored with it. And I never had the desire to subject myself to the torture of the MFA workshop, which Louis Menand memorably described as “a combination of ritual scarring and twelve-on-one group therapy.” At some point, having failed for years to write any decent fiction, I thought, “Why not try to write a true story? The thing happened; I know how the story begins, I know how it ends.” And my first attempt was decent enough to be published in a little magazine, the Georgia Review, which was, of course, encouraging. I haven’t written a word of fiction since.

All the Wrong Places is a very personal book about a dark chapter in your family’s life. You say that you felt inspired to write about your brother Dan because your mother shared her diary with you. Was it hard for your family to see the entire story when it went to print?

Parts of it were very difficult for my parents to read, as they would have to be: I’m writing about their only other son, who chose to end his life with a bullet from an assault rifle. But they’ve been remarkably supportive of the book. My sister told me she loved it. That meant a lot. My mother told me she couldn’t put it down, even as she cried through the whole second half.

As you mentioned, it was her brave act of connection and sharing that originally unlocked the book for me. She’d been keeping a diary of her thoughts about Dan, and in one of our rare moments of conversation about him, she had the impulse to share what she’d written. I found it very moving that she would offer up something so intimate. By then I had come to understand how difficult it is to talk about suicide—so difficult that it’s among our last taboos. It was not something we talked about much in our family, even though it sat there like the elephant in the room. And after my mother shared what she’d written with me, I thought maybe I could also write something that chipped away at the taboo.

It feels like you are saying in the book that your brother’s suicide shaped your adult life, both in the mistakes you made but also in the fact that you became a nonfiction writer.

It happened when I was still in the process of crafting an adult self, so I think it’s only natural that it affected everything that came afterward in my life. And I do think it’s a major part of what made me the sort of writer I became. Because the subject of suicide is so taboo, I found that the only place I could talk about it was in my own private notebooks. For years and years I had a running conversation with myself about it; if I didn’t, I feared the fact of Dan’s death would eat me alive. In some perverse way, the fact of his death ordained my becoming a writer. In order to live, I had to write—and so I did.

The sense of lost connections, or a failure to connect, gives the book a sense of poignancy, without it ever becoming maudlin.

Yes, that was a trap I wanted to avoid. I didn’t feel a need to accentuate the tragic nature of suicide. The reader is going to get it. What I wanted to do was write a quest story—a quest for how to be in the world after something like that has happened in your family.

The suicide of a family member is like a bomb going off, and it leaves everyone left behind with a lot of shrapnel and a lot of questions. How could my brother have believed that a bullet in the brain was the answer to what troubled him? And what was the thing that troubled him? For years, I didn’t know. It took some searching to unearth a plausible story, and in the meantime the fact of his death was close to unbearable. I thought about it every day for years, and it made me what I suppose a doctor would call clinically depressed.

But finding a way to live with the unbearable can result in comedy, at least in retrospect. Making the unbearable bearable is a real-life run at improvisational burlesque, and often a massive exercise in self-deception. I made counterintuitive choices. My life became deeply weird, sometimes even farcical. I managed to work myself into the wrong situation—the wrong neighborhood, the wrong job—over and over again.

The details of that impulse allowed me to laugh at some of what I had made of my life in those years, and that was crucial in writing a readable book, one that didn’t take the reader by the scruff of the neck and rub her nose in endless misery. I like to think that parts of it are pretty funny, perhaps unexpectedly so.

Part of the book is also about clandestine phone sex, which adds a touch of ribald humor but also is closely tied to the theme of an inability to connect. Was it hard to write about something so personal?

Not really. Those parts of the book were among the first I wrote, and they came pretty easily, because the experience was so strange and vivid, and so rich in narrative potential. If you’re going to write a memoir, you’ve got to be willing to confess. Having grown up Catholic, I know a thing or two about confession.

I was especially riveted by the story of your friend who developed a phone relationship with a dying man. I think that could fall under the “you can’t make this stuff up” category of nonfiction. Yet with this book you managed to do what I think good fiction generally tries to do—capture an emotional truth through telling a story.

Life is almost always stranger than fiction. How to capture some of that strangeness in a true story—and how to impose a certain shapeliness and beauty on the chaos of lived experience—is a motivating challenge for me. In both of my first two books, I wanted to write nonfiction that had a depth of feeling and an emotional impact similar to the best fiction.

Was there another memoir writer you’ve met or read who inspired you to think about your own book the way you did?

[The semi-autobiographical novel] A River Runs Through It always spoke to me because it mingled the comic and the tragic so beautifully, and deftly managed big jumps in time. But as a memoirist I was dealing with the raw material of my own life, so the challenge was to sift through my experience to discover what about it had the shape of a story. I wanted the book to have a kind of relentless narrative drive. The goal was to create that unlikely thing: a page-turner about a suicide. Mostly that involved writing and rewriting, again and again, and stripping away anything extraneous so that all that was left was essential.

Your first book, Fire Season: Field Notes from a Wilderness Lookout, could be called a modern-day Thoreauvian account of a solitary life in the wilderness. Solitariness is also a theme in All the Wrong Places. Do you think solitude is a necessary condition for you as a writer?

I’m not sure solitude is a necessary condition, but it is without question helpful. Back when I lived and worked in New York, I wrote in the mornings before setting off on my commute. I think what I’ve written since then is better, deeper, and more thoughtful for the time I’ve been given as a Forest Service fire lookout, living and working in solitude, with plenty of mental elbow room for thinking or not thinking, being creative, allowing things to bubble up unexpectedly. Part of writing, for me, is sitting and doing nothing. In order to write for an hour, I often find I have to sit doing nothing for three. Then a phrase comes, and I’m off.

What’s next for you?

Check back in six months and perhaps I’ll have an answer. This book left me feeling that I’d scraped from the bottom of the well. Now I need to allow the well to fill again. I hope to be pleasantly surprised.

You’re about to head back into the Gila National Forest to work as a fire lookout for another season. Are you looking forward to a respite from the pressures involved in being a public person?

Absolutely. I’m far more comfortable sitting alone in a lookout tower than I am speaking in front of strangers in bookstores. I’m very much looking forward to sitting quietly, communing with the birds, studying cloud shapes. It’s what I do best.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Susan Dunlap is the natural-resources reporter for the Montana Standard.

Correction, August 10: Due to an editing error, an earlier version of this story mistakenly said All the Wrong Places is Connors’ third book; it is the second he has written, though he edited and contributed an essay to a third book. The story also said the suicide of Connors’ brother occurred when he working as a reporter; he was actually a college student at the time. We regret the errors.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content