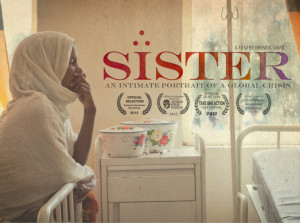

At the heart of Sister, Brenda Davis’s documentary debut, are three inspiring stories of an Ethiopian health officer, a midwife in rural Cambodia, and a traditional birth attendant in Haiti. When Davis met Goitom Berhane in Ethiopia in 2008, she was taken with his vivacious personality and dedication to solving the maternal health crisis in his country. Berhane’s example encouraged Davis to explore women’s health as an international human rights issue. Eventually, he became a central figure in her film.

At the heart of Sister, Brenda Davis’s documentary debut, are three inspiring stories of an Ethiopian health officer, a midwife in rural Cambodia, and a traditional birth attendant in Haiti. When Davis met Goitom Berhane in Ethiopia in 2008, she was taken with his vivacious personality and dedication to solving the maternal health crisis in his country. Berhane’s example encouraged Davis to explore women’s health as an international human rights issue. Eventually, he became a central figure in her film.

We meet Madame Bwa in the poverty-stricken Shada neighborhood of Cap-Haitien, Haiti. An aged woman who struggles with basic survival, Madame Bwa has delivered more than 12,000 children with no formal medical training.

In an area of Cambodia that is littered with land mines, Pum Mach puts her own life at risk so that geographically isolated mothers and their children may live through the common event of childbirth. In one of the more ghastly moments of Sister, a nineteen-year-old girl delivers her baby by caesarean section thanks to Mach identifying the child as breech and securing transportation to the nearest hospital, which is several hours away.

These moments make Sister as beautiful as it is brutal. The film showcases the passion of health workers who overcome incredibly difficult circumstances to combat the alarming rate of maternal and newborn deaths occurring around the globe — deaths that, with adequate care, are almost entirely preventable.

In The Fray spoke with Davis about her family’s experience with child mortality and the challenges of filming a tragic topic.

When did you develop an interest in maternal and child mortality?

My grandmother gave birth to sixteen children in rural Nova Scotia. Four died during childbirth and one died at the age of two. She lost her first child when she was nineteen and her last at thirty-nine. I remember my cousins coming together to buy a gravestone for all the children my grandma lost. They spoke about it casually because this happened a lot where my grandmother lived, but it had a lasting impact on me.

Why did you choose to explore this topic for your film?

As an artist, I’m interested in storytelling. If a subject is compelling to me, I want to pursue it, but I don’t want to speak for people. I want them to tell their own stories.

I was very fortunate to find people willing to tell their stories in Ethiopia, Cambodia, and Haiti. We were able to show similarities in women’s experiences, despite entirely different cultures, while also focusing on local strategies. The unifying theme to every story is a lack of access — access to basic health care, access to emergency obstetric care, and access to family planning.

How are health workers attempting to close these gaps in access?

It’s difficult to articulate just how important health workers are, and in many instances, it goes beyond the service they’re providing. In Ethiopia, Hirity Belay is a young woman who walks to places where there are no roads to provide women with the care they need to have healthy babies. While that service is invaluable, you must also consider what an amazing example she’s setting in these small villages. One of the things that inspired the name of the documentary was Hirity’s relationships. The women would often call each other “sister.” I thought this was so beautiful and warm.

In the case of Madame Bwa, being a traditional birth attendant has been passed down through her family. The work she does is important to her community, and for the most part Madame Bwa lives off donations from the families she helps. Traditional birth attendants fill a gap where there is nothing. I’m not a medical professional, but I don’t understand why so many people want to eliminate traditional birth attendants. They’re making a difference, and with a bit more support, they could be making a much bigger impact.

I found many of the scenes hard to watch, not because they’re graphic, but because they are heartbreaking. How do you approach filming people’s intimate tragedies respectfully?

In Ethiopia, we spent time in the hospital without cameras and became a familiar presence. The women often didn’t understand why we were filming or why anyone would be interested. I’d explain that we wanted to show what was going on in their communities.

Sister was definitely difficult to film, and the director of photography and I constantly struggled with the fear that we may be invading a woman’s privacy. When you’re meeting people in such intense and difficult circumstances, you constantly grapple with whether or not you’re being sensitive and respectful.

In some respects, I feel like Sister is a war movie. Women everywhere — but especially in developing countries — are fighting for their lives. What you see was exactly what was happening. The women, health workers, midwives, and birth attendants all speak for themselves and tell their own stories. It was a conscious decision not to narrate or pretend to know the answers.

What do you hope viewers take from the film?

I hope Sister encourages people to think critically about what the United States does that affects other countries — from a its inability to grow food to being littered with land mines. People should think about how they’re connected to what’s happening in other places, or how they’re complicit in it. Donating funds is awesome, but it’s not enough.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content