I celebrated every birthday under my mother’s roof with a bowl of miyeokguk, or seaweed soup. I ate it for breakfast and had the leftovers for dinner the rest of the week. When I was old enough to understand, my mother explained that it was a Korean tradition to eat this soup on one’s birthday. It was also a tradition for women to eat nothing but miyeokguk for several weeks after giving birth. That sounded great to me; I love miyeokguk.

Records of seaweed in Korean cuisine date back to the tenth century. Coastal people of the Goryeo dynasty fed new mothers miyeok (seaweed), having witnessed whales eating it after giving birth. The soup is eaten on birthdays to honor one’s mother and the pain she endured while giving birth.

Today, seaweed is widely known as a “superfood”: low in fat and calories and loaded with crucial nutrients like iron, iodine, and vitamins A, C, and E. Studies have shown it to be good for your heart and blood pressure.

Yet I love the rather mystical origin story of miyeokguk: a mother whale giving birth and then intuitively seeking seaweed in her given environment to nourish herself. The story could serve as a metaphor for Korean cuisine itself, whose traditions arose from a people’s harmonious dependence on their immediate environment for sustenance. But in the United States, where I was born and raised, our relationship to food today seems more distant from our surroundings than ever. We Americans consistently lead the world’s wealthy nations in obesity. Have we forgotten how to nourish ourselves? Where and when did we lose our way?

The co-owner and executive chef of Blue Hill at Stone Barns, Dan Barber, offers one theory on America’s problem: it doesn’t have a cuisine. “All cuisines evolved out of a negotiation that the peasants were making with the landscape,” Barber explained in an interview. “Now what could the landscape provide? And how could they make it nutritious and delicious in terms of a diet? That’s the genesis of every cuisine.” In other words, a cuisine is not just a style of cooking; it’s “a pattern of eating that supports what the landscape can provide.”

Food in America, however, evolved in the reverse manner. Thanks to the New World’s “freakish soil fertility”—as Barber puts it—the first European settlers were able to impose their fully formed notions of cuisine upon the land. In the northeastern colonies, they planted crops from England, retaining their food traditions and only occasionally replacing familiar ingredients with indigenous foods.

As the nation grew, regional food cultures—New England, soul, Cajun, Creole—did form, developed out of long-established cuisines brought over by early European colonists and African slaves and infused with the immediate environment’s indigenous offerings.

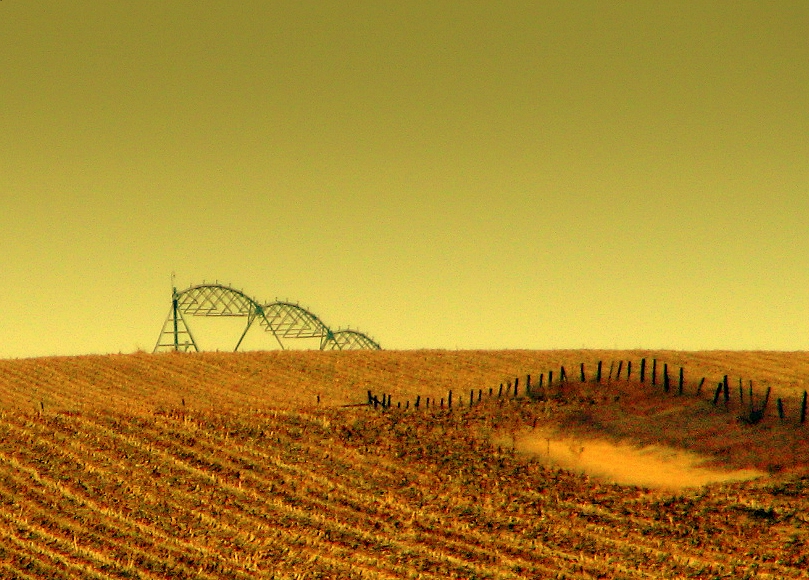

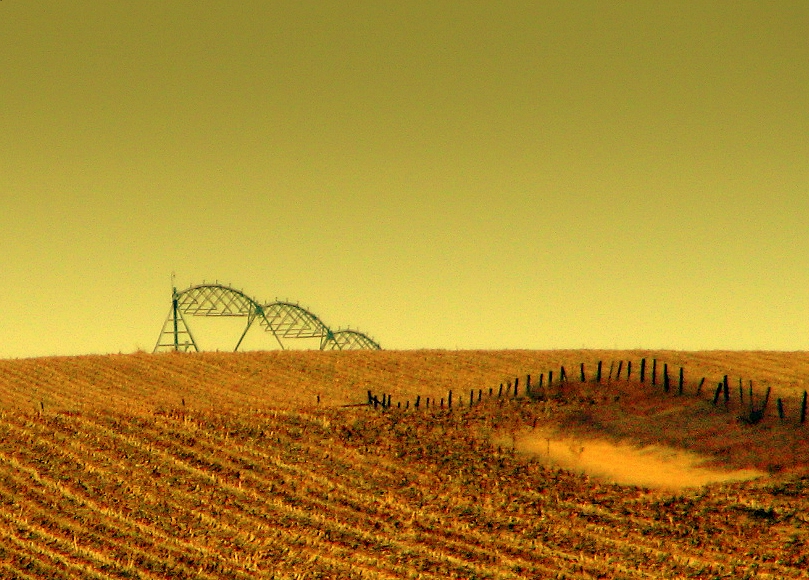

More recently, however, the industrialization of farming and agricultural technology has tamed the land, introducing monocultures of wheat, soy, and corn, whose surpluses are fed to livestock in industrial animal-feeding operations. With the abundance of a few ingredients, food is now more processed and homogenized and less nutritious than ever before. Synthetically produced flavors have replaced nature-made ones. The proliferation of fast food has narrowed our diets, too, by limiting our food choices.

Our modern food system, with all its technologies, has created an ever-growing rift between us and the rich, diverse supply of nutrients that nature provides. But we can repair our relationship to our food and health by creating and eating a cuisine that the seasons, soil, and climate can provide sustainably. Nature can produce all the nutrition that we need. Our bodies have complex systems to perceive and receive that nutrition. And we, too, possess the instinct to nourish ourselves from our surroundings, just as the whale mother knew to eat her seaweed.

Sandra Hong Sandra Hong is a freelance writer based in Hong Kong. After a stint in finance, she delved into her love of eating and cooking by attending the International Culinary Center in New York and then working in a restaurant and a cafe in Hong Kong. She devotes her spare time to running, traveling, and volunteering for the Hong Kong chapter of Slow Food International.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content