Like many other things that the city has branded and made its own (pizza, the blues, improv, hot dogs), Chicago has its own kind of politics. The structure of the city’s government is decentralized and hyperlocal, a swamp of favors, family ties, and a certain flair for the theatrical. Its leaders’ crooked dealings land on the front pages of Chicago’s papers on a regular basis. Corruption in Chicago is as constant as the Cubs’ losing streak: an inside joke that’s been done to death.

Chicago has always belonged to hustlers. In the 1830s, after a stretch of land was ceded by Native Americans, speculators saw the potential for a transportation hub. The city was built in a swamp known for its pungent onions (according to local lore, an Indian word for wild onion, shikaakwa, provided Chicago with its name).

Before Prohibition, the members of Chicago’s city council were mostly self-made men who exchanged favors for votes, giving rise to a system of patronage and cronyism. They were men with backgrounds as colorful as their nicknames: Michael “Hinky Dink” Kenna, “Bathhouse” John Coughlin, Johnny “De Pow” Powers.

They weren’t the first to make a living brokering deals between the criminal element and politicians, but they did it in true Chicago style: loudly and unapologetically. They hobnobbed with the madames, gangsters, and pimps of their districts, took bribes as their due, and ran protection rackets. When the Municipal Voters League, a reform organization, printed that Coughlin was a tool of gamblers and thieves, Coughlin demanded a retraction — not of their claims that he was corrupt, but because they had written he’d been born in Waukegan. As a native Chicagoan, Coughlin took offense.

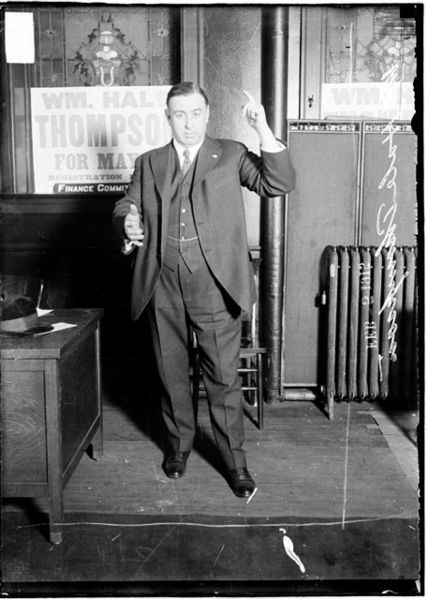

The last Republican to hold the mayor’s office was William “Big Bill” Hale Thompson. During his time in office, the Chicago Outfit, the organized crime syndicate that Al Capone would make famous, dominated the bootlegging trade. Violent turf wars broke out — between local politicians. These culminated in more than sixty bombings in the run-up to the 1928 primary elections. The editor of the Chicago Tribune once wrote that Thompson had “made Chicago a byword for the collapse of American civilization.”

The Depression turned Chicago into a Democrat’s town. A succession of slick mayors molded the city government into little more than an autocracy, complete with its own dynasties. Richard J. Daley served for five terms before dying in office in 1976. Despite an administration marked by scandals and well-publicized corruption cases, Daley is still regarded by political scientists as one of the best mayors in American history. After all, he gave us Sears Tower (now known as Willis Tower) and O’Hare Airport; what’s rampant and systemic corruption compared to that? The city loved him so much it elected his son, Richard M. Daley, after a very brief flirtation with a couple of reformist mayors. The younger Daley surpassed his father by serving for six terms before retiring.

It takes a certain kind of mindset to go into Chicago politics: a combination of brute determination, narcissism, flexible ethics, and manic tendencies — not to mention a rich vocabulary of curses. Maybe this can explain the slow-motion implosion of Rod Blagojevich’s short stint as governor of Illinois.

The son of Serbian immigrant parents, Blagojevich was born in 1956 on Chicago’s North Side. Growing up, he had a variety of odd jobs: shoeshiner, pizza delivery boy, meat packer. After a short, failed career in amateur boxing, he went to law school at Pepperdine University in California. He married the daughter of a powerful Chicago alderman, Richard Mell, who got him a clerk position with another member of the city council, Edward Vrdolyak. (Vrdolyak had been charged with attempted murder in 1960, at age twenty-two. Nearly a half century later, he would serve time for corruption.)

Blagojevich later became a state representative and then in 1996 won a congressional seat. He was young and charismatic, and he belonged to the city. He won the next two elections easily and eventually set his sights on a higher seat: governor of Illinois. He promised an end to the endemic corruption plaguing then-governor George Ryan, whose single term was marked by the indictments of seventy-nine state workers and business leaders — some of them with close ties to Ryan — on various graft charges. (Ryan himself was convicted in 2006 of mail fraud, tax fraud, racketeering, and lying to the FBI.)

Voters believed Blagojevich when he claimed to be an agent of change. But after becoming governor in 2003, he quickly alienated nearly everyone in his party, including Mell and the other men who had helped put him in power. His approval ratings were an abysmal 13 percent by the time the FBI caught him attempting to sell the newly vacant U.S. Senate seat of Barack Obama in 2008. “I’ve got this thing, and it’s fucking golden,” he said, in the now-infamous recording. “I’m not giving it up for fucking nothing.”

The ensuing frenzy was as sensational as the headlines themselves. Outrage, disbelief, and censure flooded in from all corners. Blagojevich was impeached and removed from office in January 2009.

Blagojevich went on a media blitz, appearing on talk shows to proclaim his innocence and even joining the cast of Donald Trump’s reality TV show, The Celebrity Apprentice. After a mistrial in 2010, a year later the former governor was convicted on most counts and sentenced to fourteen years in prison. He was the fourth Illinois governor convicted of corruption charges since 1973.

This year scholars at the University of Illinois at Chicago released a report, “Chicago and Illinois, Leading the Pack in Corruption,” citing new public corruption conviction data from the Department of Justice. The report concluded that the Chicago metropolitan region has been the most corrupt area in the country for the past thirty-five years, and that Illinois is the nation’s third most corrupt state. From 1976-2010, Illinois saw 1,828 convictions of government workers, including elected officials, appointees, and employees — an average of fifty per year. In Chicago alone, thirty-one aldermen have been convicted of corruption since 1973 — one-third of the aldermen who have served since then. Even nominally reformist aldermen have been embroiled in scandals, prompting the Chicago Tribune to lament that the city is a “place so crooked, even the reformers are on the take.”

It’s interesting to note that no Chicago mayor has ever been arrested, never mind convicted, on corruption charges, even as their associates, friends, and cronies have been carted off to prison. It begs a few uncomfortable questions: Are they more powerful than the governor? Are they above the law?

Today the fast-talking Rahm Emanuel occupies City Hall. The former U.S. House Democrat from Illinois resigned as Obama’s chief of staff to run for Chicago mayor after the younger Daley announced his retirement. (Replacing Emanuel for a time was William M. Daley, the former U.S. commerce secretary — and brother of the man Emanuel would succeed in Chicago.) Emanuel has shown himself to be every bit the autocrat as the Daley father-son dynasty was. The city council acts more like a Greek chorus than a governing body, unanimously agreeing to his budget despite cuts to social services, granting him blanket spending authority for last May’s NATO summit, and backing his speed-camera ticketing plan.

Chicago’s politics are America’s politics — a crossroads of race, money, power, and greed, magnified and put on display. In some respects, the city has come a long way. Its leaders are no longer throwing bombs, gunning down rival politicians, or openly cavorting with mobsters. Yet its politics remain one of the most reliable spectator sports in town. Its cast of characters is huge and colorful, its daily drama edgily entertaining.

Carl Sandburg’s elegant summaryof Chicago gave it one of its proudest nicknames, “City of the Big Shoulders”:

Come and show me another city with lifted head singing so proud to be alive and coarse and strong and cunning. Flinging magnetic curses amid the toil of piling job on job, here is a tall bold slugger set vivid against the little soft cities …

There is pride here, to be sure, an ironic swagger that comes as a consequence of such a checkered history. “Chicago ain’t ready for reform,” Alderman Mathias “Paddy” Bauler famously said in 1939. It still ain’t, in plenty of ways.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content