Fifty years after the March on Washington, we are well versed in the visual cues of the civil rights era: grainy black-and-white photos and footage of peaceful protesters being accosted by angry mobs, beset by dogs and water cannons, and enveloped in plumes of tear gas. John Lewis, one of the giants of the civil rights movement, not only lived those scenes of protest and violence — a beating by Alabama state troopers fractured his skull — but he worked to make sure the struggle led to real political and cultural change by the era’s end.

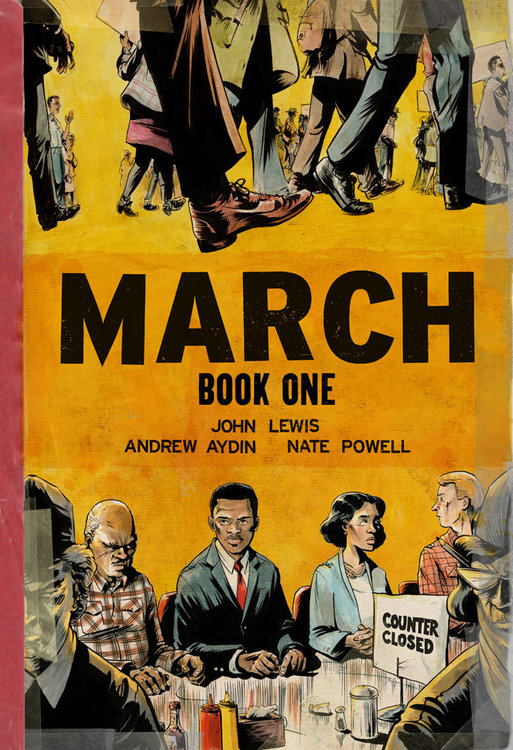

Now Lewis and his collaborators offer a new visual take on the protests and the people behind them, in the graphic novel March, an illustrated (and unconventional) autobiography of the civil rights leader and longtime member of Congress. In a way, the book brings Lewis full circle: Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story, a comic book published in 1956, helped inspire him to take up the nonviolent cause as a teenager.

There’s a long tradition of autobiographical comics, from Harvey Pekar’s American Splendor to Jonathan Ames’s The Alcoholic to Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis (the basis of an Academy Award-nominated animated film). But Lewis is not just any other thoughtful voice of retrospection. One of the original Freedom Riders, he was a founding member and then chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which was instrumental in organizing some of the era’s most important sit-ins and other nonviolent protests against segregation — including the March on Washington. (The youngest speaker that day was Lewis, then twenty-three years old.) He also played a prominent role in another of the era’s iconic demonstrations, the Selma to Montgomery march, the source of the scars he still bears on his head. Lewis went on to a career in politics, representing Georgia’s fifth congressional district since the late eighties and now serving in the House Democratic leadership.

Lewis, we learn in March, was an unusual child. His parents were sharecroppers, and Lewis grew up on a farm in Alabama. As a boy, he raised chickens, not only giving them names but even devising a makeshift incubator because his family couldn’t afford the one in the Sears, Roebuck catalogue. His youth in the forties and fifties is captured in a series of panels: Lewis as a boy honing his sermonizing skills before a congregation of chickens (his first ambition was to become a preacher). Lewis as a young man first hearing King on the radio and becoming inspired to embrace nonviolence. As the narrative of Lewis’s life advances, March reminds us of the events transpiring in the background — from Rosa Parks’s civil disobedience to the killing of Emmett Till to the Brown v. Board of Education decision that struck down school segregation — all of which shaped Lewis’s worldview and led him and others down the path to protest.

The best dramatizations carry a sense of dread, or anticipation, even when you know the outcome. Like a train slowing a moment on the tracks and, by degrees, gaining momentum, March crackles with a sort of inevitability. We watch as Lewis and other young protestors in the Nashville Student Movement, a nonviolent direct-action group fighting against segregation, subject themselves – and each other – to a series of humiliating tests, preparing them for not only the harsh words, but also the physical retaliation they were likely to encounter. As Lewis points out, “For some, it was too much.” The hardest part to learn, he adds, was “how to find love for your attacker.”

Once the book settles into the sit-ins by Lewis and his fellow activists in downtown Nashville, you’re firmly locked in — you’re enlisted. And, here, really, is where Nate Powell’s art takes off.

Once the book settles into the sit-ins by Lewis and his fellow activists in downtown Nashville, you’re firmly locked in — you’re enlisted. And, here, really, is where Nate Powell’s art takes off.

When the sit-ins begin, the artwork becomes darker, the pages soaked with dark ink, the lines sketchier, shadowy, conveying the pain and fears of the nonviolent protestors. Powell’s style is somewhere in between the worlds of photorealism and animation, the images at times seeming to move on the page. It’s detailed enough that each face is distinctive from the other, with exquisitely rendered backgrounds undoubtedly reflecting Powell’s research on the downtown buildings of that era. His use of black and white is not just an artistic choice; it intensifies the action by making the reader slow down to see the details.

Part of a planned trilogy, March ends right after Nashville Mayor Ben West announces to the press and a group of protesters at city hall that he will support the desegregation of lunch counters. On May 10, 1960, six downtown stores, the book tells us, “served food to black customers for the first time in the city’s history.” We’re left with scenes of black Americans sitting at a lunch counter some three years before the historic March on Washington.

In August, Lewis spoke at the fiftieth anniversary of the March on Washington, sharing the podium with former presidents Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton and President Barack Obama. The last surviving speaker of the original march, Lewis noted that the country still has “a great distance to go before we fulfill the dream of Martin Luther King Jr.” And yet, he said, change had come — as March itself suggests, in its introductory depiction of the inauguration of the country’s first black president. “Fifty years later we can ride anywhere we want to ride, we can stay where we want to stay,” Lewis said. “Those signs that said ‘white’ and ‘colored’ are gone. And you won’t see them anymore except in a museum, in a book, on a video.”

Sometimes I hear people saying nothing has changed, but for someone to grow up the way I grew up in the cotton fields of Alabama to now be serving in the United States Congress makes me want to tell them come and walk in my shoes. Come walk in the shoes of those who were attacked by police dogs, fire hoses and nightsticks, arrested and taken to jail.

March invites the reader to walk in the shoes of Lewis and the many other men and women who sat down, picketed, and marched for justice, without violence and with a great love for their attackers — and for their country.

Cornelius Fortune is a journalist whose work has appeared in the Advocate, Citizen Brooklyn, the Chicago Defender, Yahoo News, and other publications.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content