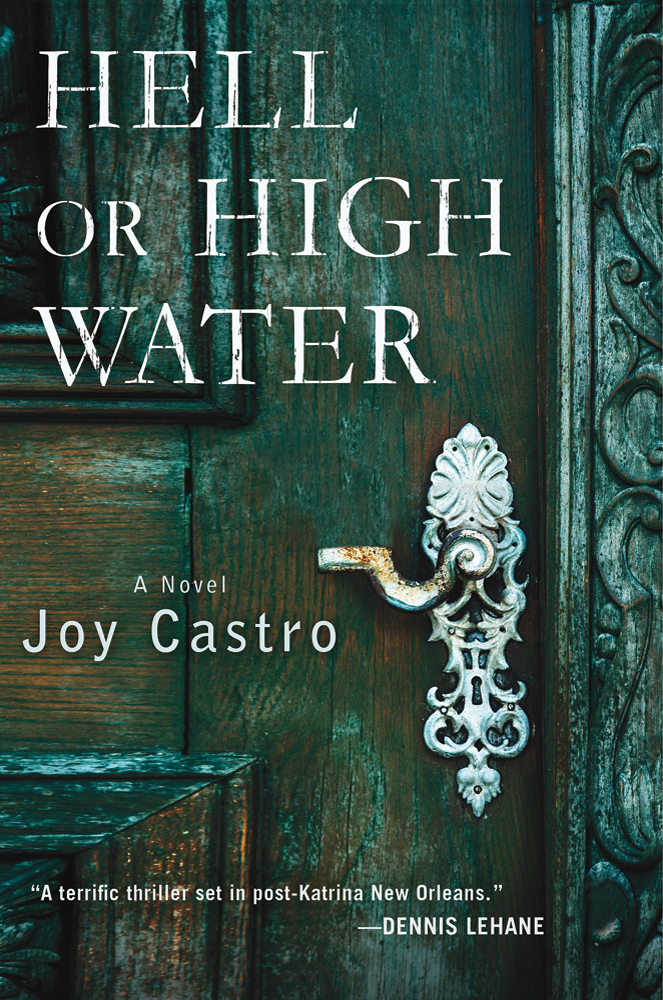

Hell or High Water: A Novel

By Joy Castro

Thomas Dunne Books. 352 pages.

When Joy Castro was fourteen years old, she ran away from her abusive family, who had adopted her at birth. Raised as a Jehovah’s Witness, in an environment where she was to proselytize “the truth,” Castro sought refuge in the church. But after the church failed to protect her from the emotional and physical anguish she endured on a daily basis, Castro reached beyond their teachings to forge her own path to salvation.

This past year has been a busy one for Castro. Her 2005 memoir detailing her childhood, The Truth Book, was re-released. This coincided with the publication of Island of Bones, a collection of essays that continues Castro’s story of survival and resilience as she moves through adulthood. In addition to her nonfiction work, Castro’s debut crime novel Hell or High Water also recently hit the shelves.

In The Fray spoke with Castro about letting go of traditional concepts of faith, becoming a parent, her attraction to the crime fiction genre, and her definition of truth.

You were raised in an environment where the concept of “truth” was steeped in paradox. What is your understanding of truth now?

When I was growing up as a Jehovah’s Witness, “the truth” was the short-form term we used to refer to the belief system of our religion. Someone was “in the truth” or “not in the truth.” From infancy, I was taken to the Kingdom Hall for five hours each week, and my mother read to me regularly from Jehovah’s Witness literature at home. We went preaching door to door. I prayed morning and night and before every meal in the way I had been taught. So, it was pretty much a full-immersion experience.

I was a believer. Another option was impossible for me to conceive when I was a child. It was only as I got older — ten, eleven, twelve — and had been exposed to enough contradictory material at school that I began to question the tenets of our faith. I ran away at fourteen and stopped attending the Kingdom Hall at fifteen. As we know, “truth” is something that’s energetically debated by political and religious systems all over the world, so it wasn’t as though, when I was fifteen, I moved from a brainwashed state into one of clarity. Truth remains up for grabs.

Now, I just prefer to believe in kindness, compassion, the attempt at honesty about one’s experience and perceptions, and the effort to create justice. As a species, we need a variety of competing voices, competing subjectivities, in order to be able to figure out the best strategic ways forward.

You’ve written about there being freedom in accepting one’s own imperfections and inability to conform to social expectation. As a woman who grew up in poverty and a survivor of childhood abuse, how have you learned to constructively carry the confines of your personal history?

It has meant relinquishing the dream of having had a beautiful childhood — or, within academia, the psychic comfort of having an intellectual pedigree. I cannot compete with people who sailed or had families full of love or went to Harvard. I cannot compete with people who were not raising a child in poverty or riding city buses or doing without. By writing transparently about my own experiences and making them public, I’ve gradually let go of the desire to have been someone else, someone more socially acceptable.

How did unintentionally becoming a parent influence this process for you?

Becoming a parent at twenty, while perhaps not ideal in terms of timing, was overwhelming and transformative for me. Parents will tell you that their souls broke open when they had children. That was true in my case. That radical empathy, that willingness to sacrifice and defend, that compulsion to make a better world for all children — it’s so powerful.

For me personally, it was an opportunity not to neglect, not to abandon, not to abuse, not to commit suicide — all the things my own [adoptive] parents did that left my brother and me damaged and bereft. It was a chance to face down the deep, brooding fear of becoming an abuser. It offered a long series of moments in which to choose to say “yes” to love and growth. While that sounds like a positive, obvious, easy thing to do, it’s not so easy for people who’ve shut down after multiple traumas. For me, opening up and committing to someone in such a profound way was risky and difficult. And, ultimately, so worthwhile.

Before my son was conceived, I was never the sort of person who consciously longed to have a child. Unexpectedly becoming pregnant derailed what I thought my life would be, but in a good way. It carved out a kind of generosity and compassion in me that probably would not have otherwise developed.

My son is twenty-four now, so I’ve been this person for a long time. Lately, my focus has been on changing into someone who does not have a child, like a compass that steers all her choices, at the center of her life anymore. That has been the real challenge for me for the past few years. I think I’m getting the hang of it.

For those of us with unenviable pasts, writing can be a kind of coping mechanism employed to escape or manage the darker realities of our lives — which makes writing both painful and necessary. Has this been your experience?

For me, writing has been a beautiful gift, an escape — as you say — and a way to manage painful truths. It has also been one of the most profound pleasures of all. Using our imaginations to shape and reshape the world is a magnificent gift. What power! And hearing our own voices and exploring our own thoughts in a noisy world is such a soothing, beautiful, private thing that writing allows us to do. I’m grateful for it.

You’ve recently published your first crime novel, Hell or High Water. Does writing crime fiction allow you to explore issues in a way your previous work did not?

As a child and adolescent, I loved reading mysteries. I enjoyed the puzzles and the suspense. I still do. But now, as a writer of crime fiction, I’ve come to appreciate how devoted the genre is to issues of justice. Writing crime fiction has been a method for translating the insights of the academy for a broad audience. I’m not sure crime fiction provides additional freedoms; it’s just a different vessel for exploration.

Your novel is set in New Orleans, a place known for its stark contrast between the lives of blacks and whites, rich and poor. What do you find compelling about placing a struggling Latina journalist in this post-Katrina backdrop?

Your novel is set in New Orleans, a place known for its stark contrast between the lives of blacks and whites, rich and poor. What do you find compelling about placing a struggling Latina journalist in this post-Katrina backdrop?

There are a couple of reasons. First, like many people, I love the city of New Orleans. My husband grew up on the north shore of Lake Pontchartrain, and he lived, went to college, and worked in the city as a young adult. When we met in graduate school, he took me home to meet his family, and I fell in love with the city as I was falling in love with him. I’ve been going there regularly for twenty years now, and my affection and respect for New Orleans made me want to set a novel there.

You’re right about the black-white construction of race and ethnicity in New Orleans. While there has famously and historically been a great deal of mixing, it has usually been defined along a black-white continuum, though the influx of Latino construction workers and their families has shifted the demographic somewhat since Katrina. I was interested in exploring how a character lives her Latinidad in an environment where there’d been almost no Latino community.

You have personal experience with that as well.

Being a Latina without an ethnic community was my own experience growing up. Though I was born in Miami, we quickly moved to England, where we lived for four years when I was little. Then, after two more years in Miami, we relocated to West Virginia, where I lived until I graduated from high school. In the 1980s, I was the only Latina student in my high school, and my Spanish teacher was the only Latina I knew outside my family. Being culturally isolated is something I knew well. So, I wanted to tell a story about cultural isolation, and the strange pressures and loneliness that come with that.

There are similar feelings of isolation that come with “escaping” poverty and climbing the social ladder that your main character contends with throughout the novel.

I don’t see [the main character] as a social climber in the negative way we usually construe the term: someone who sacrifices her ethics and true feelings to attain prestige and wealth. She’s a newspaper reporter, after all, because she believes in justice. But it’s true that she did climb her way out of poverty, and she did leave some people behind, which she regrets.

Bright, poor, ambitious people in our society often live that painful story. Our social structures frequently push gifted young people to choose between pursuing their talents fully and remaining in the community that raised them. Either way, people sacrifice. It’s unfortunate.

A theme in your writing is finding redemption in telling the truth, though the result is not always a victory. Why do you embrace the mistakes people make?

It just seemed more realistic, more true to what I’ve experienced in the world. I have failed in ways that schooled my soul. Even when we’re trying, we make mistakes. We have blind spots. Knowing that about myself helps me to be compassionate with others who fail.

It’s often the case that various forces — commercial forces, political forces — don’t want uncomfortable truths to become public, and they sometimes have the power to squelch those stories. Other times, the route to a public hearing is beautifully clear. It’s a process, and it’s a choice. There will be hits, and there will be misses. The important thing is to keep telling your truth.

Mandy Van Deven Mandy Van Deven was previously In The Fray’s managing editor. Site: mandyvandeven.com | Twitter: @mandyvandeven

Dear Reader,

In The Fray is a nonprofit staffed by volunteers. If you liked this piece, could you

please donate $10? If you want to help, you can also: