- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, / But in ourselves, that we are underlings. —Cassius in William Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar

Beware the terrible simplifiers. —Jacob Burckhardt, Swiss historian

Victor Tan Chen Victor Tan Chen is In The Fray's editor in chief and the author of Cut Loose: Jobless and Hopeless in an Unfair Economy. Site: victortanchen.com | Facebook | Twitter: @victortanchen

Our pain, and how we bear it, defines us. It is only through suffering that we can appreciate joy, and it is only during times of duress that we can know how strong we are. Trauma alone can tell us if we will break under the stress, or if we will persevere to thrive during better times. As spring spreads across the land, I see physical evidence of nature’s power of perseverance in the flowers that bloom and the leaves that burst forth after the long, cold winter. In this issue, we look at the power of human resilience.

We begin with Stephanie Yao’s stunning visual essay Afghanistan, which reveals a strong people struggling to move beyond their war-torn past. Accompanying these images is Angie Chuang’s essay Life after the theocracy, which highlights two university professors’ memories of life in Kabul, Afghanistan before the Taliban.

Next, we look at the trauma that individuals inflict upon themselves. In 1999, journalist Ted Conover wrote the book Newjack about his experiences as a guard at New York’s infamous Sing Sing prison. This project required Conover, a normally reserved and peaceful person, to adopt the persona of a hardened corrections officer. In his story Crossing the line, Rafael Enrique Valero explores how much of his true self Conover was forced to repress and the effects this experience continues to have on his psyche.

Another repressed trauma is the collective wounds of the legacy of slavery. Barack Obama’s historic presidential run has brought the simmering issue of racial tension to the forefront of popular culture and has prompted the art world to ask whether art created by African Americans is “black art.” Michael Miller explores the debate in his article Is it black art, or just plain art?

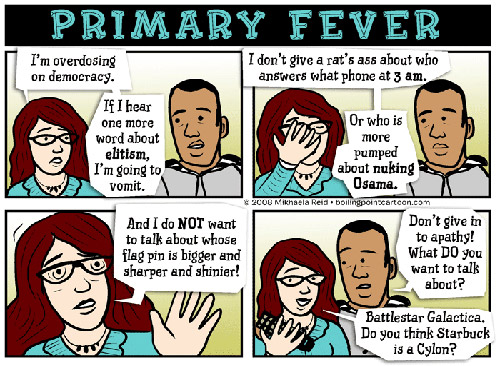

The best way to overcome the past may be to look to the future. This is the thinking in the 20 states that allow 17-year-olds to participate in the primary process, as long as they will be eligible to vote in the fall. In Should 17-year-olds vote in the primaries?, Jane Wolkowicz considers both sides of the issue, including the first-hand experiences of a 17-year-old who participated in Minnesota’s Republican Caucus in February.

Courtney J. Campbell takes us away from the democratic process and shares five poems that explore the love, loss, and life in Brazil. Accompanying her poems are photos that evoke a strong sense of place, lending her verse a visceral power.

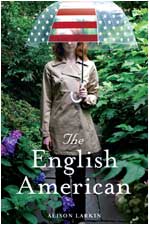

And last but never least, our books editor Amy Brozio-Andrews has reviewed Alison Larkin‘s novel The English American, which considers a British woman’s struggle to reconcile her American roots when she reconnects with her biological parents.

Aaron Richner

Editor

St. Paul, Minnesota

Aaron Richner I am a writer/editor turned web developer. I've served as both Editor-in-chief and Technical Developer of In The Fray Magazine over the past 5 years. I am gainfully employed, writing, editing and developing on the web for a small private college in Duluth, MN. I enjoy both silence and heavy metal, John Milton and Stephen King, sunrise and sunset. Like all of us, I contain multitudes.

While nature versus nurture may be one of those perennial questions, for people like Pippa Dunn, the protagonist of Alison Larkin’s new novel The English American, it’s not just academic. Pippa is the eldest daughter in a stiff-upper-lipped British family; she knows how to make a proper cup of tea, likes Marmite, and so on. However, where the rest of the Dunn family is neat and orderly, quiet, and focused, Pippa is outgoing, messy, artistic, and spontaneous. She’s always losing her things, forgetting to scrape the bowl clean before putting it in the sink, and she secretly hates Scottish dancing. She’s not happy at just any old job — she wants to follow her bliss and write plays. Pippa’s sure that her personality traits reflect those of her birth parents; she’s known that she was adopted since she was a small child. Now, as an adult, Pippa learns her parents are American — Southerners to be exact.

Feeling rudderless and out of place in England, Pippa tentatively reaches out to her birth mother in the United States, hopeful that she will measure up to the ideal that Pippa’s carried with her all these years: “She was beautiful, and delicate, with red hair, like mine, only hers wasn’t springy … The sight of her filled me with warmth and made all the fear go away.”

Her reunion with Billie, a flighty and exuberant redhead, is at first validation for Pippa — here is the woman from whom she inherited her enthusiasm for life, her creativity, and her relaxed attitude toward tidiness. Pippa also reconnects with her father Walt, a Washington, D.C.–area businessman who is actively involved in international affairs.

Joy and relief at finding her appearance and personality reflected in the people who gave her life soon turn to the cold realization that while Billie and Walt may be her parents, they don’t behave like family. Billie’s manipulative attempts to make Pippa reciprocate her neediness in the relationship and Walt’s hesitance to divulge Pippa’s existence to his wife and children leave Pippa feeling as out of place as she did before.

The English American is threaded with a romantic subplot that expertly and subtly evokes Pippa’s assumptions about other people’s identity as she struggles with her own. It provides a nice twist to the main storyline, save for when it involves Nick, a tortured artist type whom Pippa thinks she loves from afar, and who appears in the book almost exclusively via email messages. Where the relationship between Pippa and Nick is concerned, the storyline goes off the rails a bit, since so little about Nick is revealed until the final chapters, and the only communication between him and Pippa is through email; he’s a comparatively flat character.

Alison Larkin’s take on the issue of identity, while couched in a fast-paced contemporary novel, infuses the subject with realism, humor, and compassion. Larkin’s writing is at her finest when she is plumbing the depths of Pippa’s psyche. The novel echoes elements of her one-woman show, The English American. Larkin’s own life aligns with Pippa’s somewhat, as Larkin too is an American-born adoptee raised by a British family.

From the red tape and bureaucratic delays Pippa encounters in trying to obtain the names and contact information of her birth parents, to introducing herself (albeit with a posh British accent) in a bar as a “redneck,” Larkin’s ability to know just when to use a light touch buoys the darker, more emotionally powerful scenes in which Pippa’s self-reflection takes her to the depths of acknowledging who she is, who she wants to be, and how much she may or may not owe her parents.

Pippa comes to realize it is up to her alone to reconcile her roots and her upbringing. Until she can navigate the rocky boundary between genetic and environmental influences, she can never feel comfortable in her own skin. And while people may continue to argue about the influence of nature versus nurture for as long as they’re able, at least Pippa Dunn finds peace as she settles the question for herself.

And other reflections on two of the oldest cities on Brazil’s northeast coast.

And other reflections on two of the oldest cities on Brazil’s northeast coast. her children

one day she stopped at the market

where her old lover once had a stand

the lolling red of tomato

the serenade of bell pepper

the seduction of cilantro and cashew fruit

o! what a time they had!

as curfew came and passed

she found the

sidewalk again

it was not too difficult

it was right where she had

left it that one day

so many years before

when the sirens came out

and the vegetables

learned to grow in

the colors of march

no, it was not too difficult

and when she picked up

her feet

they were

they were her

children

tall children

though not quite

as tall as they used to be

you would not recognize her

she is a hurricane filter

a richter scale

the contents of a secret bag

hidden in a lingerie drawer of

planned confession and

careful compromise

inside her right hand

she carries a prepaid response

inside her left a change purse

of identities

she blows leaves to the

air as she walks

on her mind

a list of casualties

in her stride

a pen to check

unopened boxes

you would not

recognize her

in her hair

an army of lice and

city pollution

in her shorts

a brigade of

tourists with foreign accents

she is a fire escape

a mathematician

a physicist

a politician

a pressure cooker of unchained recipe

and the doubled-over flags of pride

in the stretch of her trunk

golden lava fresh from the

core of the earth

in the bough of her arms

each revolution the moon

dreamt of and was denied

thirty days later

thirty days later

he moves thick feet in hot mud

he was once an orphan

but is no longer

now, he is a crab drifting

inside his brother’s hat

This, he says, is not the river —

it is water

a hat in a river that runs

counter current or on its side

far from people who run

along the shore peering into

the water in search of crabs or

orphans or young men named Carlos

“Bet you can’t swim across

that river, Carlos.”

“You bet I can!”

thirty days later

he is a crab drifting

in a hat where his brother

still swims upstream

in defiance

far from

that place called

forward where

boats carry lies to

no family with no home

to receive them

his meteors, his sea

he is not a man anymore

he is the ocean at midnight

high tide on low shore

a balcony of late-night conversation

in his body there is dark sky

light sand

red words —

words that curl

then unbend then curl

then unbend along

his infinite blackboard

he is the ocean behind him

he is the balcony in front of him

he is cigarette embers in a

dance of swirls and dashes

he is an ember

now neon lights

he is another

now meteor shower

he is a ball of dialogue

mixed with saltwater

and seaweed

he breathes

he pulls it all in

the balcony across the street

the ocean at his back

the sand below his feet

like a fishing boat of meteors at deep sea

out of the egg yolk shavings of an emperor

when i crawl out i will be a breaking weather system

i will crawl until i am a perfectly shaped round breast

in the center of my own hurricane oyster

again

when i crawl out

out of the staged battle

out of the conscious nightmares

out of the sleeping insomnia

out of the cold glaring nudity of your sun

i will be a monolith of marble swimming

a coliseum of the tide

i will crawl out

of the barred bottle

of the painted humility

of this note card and staple and paper clip monastery

out of the half-fried egg runny yolk of your vast shadow

your dominant violin tuning

your lampshade oppression

out of your bubble gum jealousies

and bottle opener teeth

out of your five-hundred ton fascist chains of government

and its innumerable unpredictable constitutions without constituents

and i will be, i will be, i will be — i will not hide

between creased pages anymore

i will not be an estranged compliment fallen

from the door hinge of an emperor

nor the violence of insult shavings on a chocolate cream pie

i will be white noise

the sound of static

the ocean in a shell on a beach in the ocean

and no matter how long you search amidst the sands

raking with your crab pinchers and your sting ray hands

you will never find me again