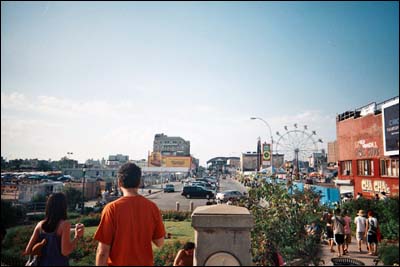

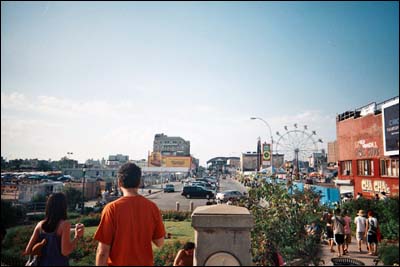

On the roof of Gregory & Paul’s hotdog and beer stand is a statue of a paunchy man giving the thumbs-up. He’s holding a hamburger so faded one suspects it was fresh off the grill 30 years ago. The man is covered in graffiti, and so is the old-fashioned rocket ship with which he shares the roof. Back in the day, it would not have looked out of place in a Flash Gordon serial; today its blue and red paint has faded, and its white spots are splattered with yellow rust.

The sign on the top of the beer stand says “Astroland Park,” a reminder of a time when Coney Island was somebody’s idea of the future. Though the area has currently lost its former space-age shimmer to time’s onward march, it still inspires futuristic thinking — and not just the thinking that has it slated for massive commercial renovation in the coming months.

Day-trippers and beach-lovers have been visiting Coney Island for centuries, and in 1864, the West End Terminal, the area’s first train station, opened. But at the beginning of the 20th century, as Brooklyn grew in popularity, the New York City authorities and the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company had the West End Terminal demolished and rebuilt with the most innovative, flexible transportation technology available, including a then unheard-of eight tracks and four platforms.

The new station, named the Stillwell Avenue Terminal, opened on May 29, 1919. Shortly afterward, Surf Avenue’s bustling boardwalks and amusement parks, like Steeplechase Park and Luna Park, made Coney Island one of the most popular vacation spots in all of New York; at the height of its popularity, the area had more than a million visitors a day.

Over time, Stillwell has grown into the largest above-ground terminal in New York City and one of the largest in the world. And since its 2005 renovation and reopening, it has become the first and biggest solar-powered terminal in the world, says Gregory Kiss of Kiss + Cathcart, Architects, the architectural firm that helped plan the reconstruction.

Kiss, a skinny man with a calm, professor-like demeanor, walks along the bridge that links all four platforms, pointing with pride to the panels above him. Kiss and his company worked with the New York Transit Authority to design and build the 80,000-square foot terminal shed that covers the platforms like a stadium dome.

In many ways, the Stillwell Terminal feels like the first attraction that subway users see upon arriving at Coney Island. The platforms are constructed with faded periwinkle- and white-colored steel, and are markedly free of the grime and graffiti coded into the DNA of the New York subway experience. Yet the disembarking teenagers and nuclear families rarely pause to look upward at the roof’s phalanx of panels, as such gawking is for tourists, and there are beaches, myriad forms of deep-fried batter, and the Cyclone to attend to.

If they did look up, they would see a ceiling composed of 2,730 five-by-five panels, which are two layered sheets of industrial glass that have sandwiched between them two squares and two rectangles of semitransparent photovoltaic glass. The intersecting lines between these sheets form crosses of light when looked at from below.

Photovoltaic glass is a type of solar cell that captures the energy of the sun and converts it into direct current electricity. Kiss estimates that there is more than 50,000 square feet of it in the shed. “In most ways, they really are the best source of energy, period, because they are solid state with no moving parts, no emissions of any kind, and they produce the most energy when you need it the most — typically, in the middle of the day,” Kiss says. “This is the biggest project in the world that uses this kind of technology, integrated into a building structure.”

The shed’s solar panels represent the successful union of architectural design and fuel efficiency. They are also very, very shiny. The silvery glow of solar cells make the terminal feel like something more akin to Disney World’s Epcot and Tomorrowland amusement parks than the nostalgic charms of Coney Island. When viewed up close, a vantage point made possible by the nearby Wonder Wheel Ferris ride, the ceiling resembles a mirrored disco ball that has been unraveled and fashioned into an airplane hanger. Taken in as a whole from 150 feet in the air, the terminal and the rest of Coney Island’s attractions seem symbiotically out of time: Astroland Park and the rest of Coney’s attractions a living postcard from half a century gone by, and the terminal shed an image that arrived a few years ahead of everyone else’s schedule.

Construction time again

Last year, the New York state government announced the “15X15” plan to reduce electric energy usage in New York by 15 percent by the year 2015. The plan seeks to address the rising cost of energy by reducing the state’s reliance on fossil fuel–burning power plants. The “15” initiative calls for an increased investment in clean power options and greater energy efficiency, two areas Kiss understands well.

Kiss, 49, was born in Toronto but grew up in New Jersey around Princeton. He received his bachelor’s from Yale and his Master of Architecture from Columbia University. In addition to authoring technical manuals for the Department of Energy, his lectures on advances in solar technology and how they can be used with architectural design have taken him across the globe, and his projects have been developed everywhere from Panama to Native American reservations.

He moved to New York to study architecture in 1981, and in 1983 his newborn firm had its first commission: to design a solar panel manufacturing factory. Ever since, he’s had an interest in integrating solar technology and efficient energy practices into architectural design.

His firm has constructed a number of environmentally forward-thinking projects in the city, including the sun-fueled, self-sustaining Solar One community education center by the East River. The center, which resembles a suburban home outfitted with a downward-facing, panel-lined roof, teaches energy conservation techniques to New York students and residents, and also hosts dance and film events.

In 1998, Kiss and his company were hired by the New York Transit Authority to help revitalize the dilapidated Coney Island Terminal. Though the area was synonymous with the Roaring ’20s, after World War II it struggled to remain relevant. The area faced competition from Jones Beach, as well as the rising popularity of then-burgeoning entertainment options like television and air-conditioned movie theaters. In 1946, the popular Luna Park closed after being ravaged by fire, and Steeplechase Park closed in 1964 following a series of accidents and the rise of crime in the area. By the 1970s, the area had become so deeply synonymous with drug- and gang-related crime, much of it linked to notorious low-income housing projects like Surfside Garden, that commercial developers were wary about investing in the area. By the 1990s, the once mighty Coney Island shrank to just four blocks of roller coasters and shows, with The New York Times reporting more than 50 unoccupied lots in the area.

Kiss remembers visiting Coney Island when he first moved to New York in the early ’80s. Back then there were hypodermic needles in the sea and fear in the air. And it only got worse as years of saltwater-infused air, as well as citywide neglect, accelerated the rust and decay of the platform’s metal.

Physically, the terminal was close to collapsing. “It was pretty scary. The steel columns down below these tracks and in many other places were corroded away to almost nothing, so there was some degree of danger there. It had to be replaced,” Kiss says. “This was an expensive project, not the sort of thing you do lightly, but as a matter of safety, it had to be done.”

Kiss + Cathcart was hired to create a new ceiling. The terminal once had individual roofs over each platform, but the Transit Authority wanted a giant roof that covered all of them. It had to be aesthetically pleasing, it had to be durable, and it had to be low-maintenance and easily fixable. Also, it would be nice if the structure could multitask.

“They thought, ‘well, this station has been here for almost a hundred years, and it will hopefully be here for another century or more.’ They have very long planning periods,” Kiss says, “and they figure that it might as well be generating electricity as it’s sheltering the station.”

Kiss and his team worked with the Transit Authority to integrate the energy-saving photovoltaic glass into the structure, and designed it with a state-of-the-art, silver and glass retro-futuristic look that would blend in well when subway passengers viewed the terminal on the same horizon as Coney Island institutions like the Wonder Wheel and the Cyclone. The firm took care to use recycled steel and aluminum, and Kiss even designed the roof to have wires that delivered a mild shock to keep birds from nesting on it.

Although they came to Kiss wanting a forward-thinking structure, the Transit Authority still had to be convinced that the project could actually work. “[We had to] show them why this makes sense and why this is not a finicky, scary, fragile technology, and why it is very reliable, and how it can be done in a way that if something does go wrong, it can be fixed.

“One of the most satisfying things to me was really the process of dealing with this very large organization that, for very good reasons, tends to be very conservative, and working through the process of educating them and understanding their needs,” he says. “It affected the design a lot; we did a lot of work and made a lot of changes to make this a very user-friendly, maintainable facility and so on.”

Power, houses

The total rebuilding of the terminal cost $250 million, some of which is returned in the form of energy savings.

The sunlight collected by the photovoltaic glass is fed into a conversion device that creates alternative current electrical energy, which is then fed into the grid for the entire station, including the main office, police stations, and underground lights. None of the collected energy is used to fuel the actual subway trains, as Kiss says that utility companies are very strict about how much power can leave an installation, and the Transit Authority prefers to sidestep the issue by keeping the energy within the local grid. “The power that is generated is used within the system,” he says.

“Another way to look at it — this project is unusual and it’s hard to get your head around it — this station produces enough electricity to provide all of the electricity for about 33 average single-family houses in this part of the country,” he says. “Total, per year. It’s a significant amount of energy.”

Green days

Because of the difficulty of efficiently transporting electricity into the city from outside the city, 80 percent of the energy for New York City is generated by fossil fuel–burning power plants within city limits. These power plants contribute to unwanted citywide pollution, so Kiss thinks it’s only a matter of time before every city-owned structure that has sunlight falling on it will be outfitted with solar cells.

“The sun is giving off about probably 850 watts per square meter of energy, and it’s basically going to waste right now,” he says. “All it’s doing is heating up the sidewalk.

“In fact, it’s worse than that, because in most cases city buildings with a black roof, the sun is heating up the roof, heating up the building, and we are cranking up the air conditioner to counteract that. So we’re wasting all that energy, and there is an enormous capacity to harvest and use this energy in a very positive way in the city.”

There are several ways of getting power from the sun: Solar thermal power stations use sunlight and mirrors to heat up a liquid that drives an electric generator. But photovoltaic cells are the most popular form. Though solar panels have existed since the 1800s, the first solar cell was patented in 1946 by semiconductor researcher Russell Ohl. The company for which Ohl worked, Bell Laboratories, discovered that certain forms of silicon were markedly sensitive to light. The company was the first to create a device to harness energy from the sun; it had an efficiency of around 6 percent. Driven both by America’s space exploration efforts and the gas crisis of the 1970s, the technology continued to slowly grow in efficiency, popularity, and affordability, but has yet to achieve widespread household acceptance.

Even today, many think that solar panel technology, especially photovoltaic glass, is too exotic, too expensive, and not ready for mass use. Kiss wants to prove that cutting-edge technology and innovative design can fit into a reasonable budget.

“There is this sense among a lot of people, even environmentalists, that ‘yeah, solar is great, it’s expensive, but we shouldn’t even worry about the cost, we should do it anyway,’” he says. “I find that kind of an unfortunate attitude. By doing things like [Stillwell], you can make the technology much more economical than it would otherwise be. It is a struggle, but that’s not a reason not to do it.

“You don’t see more of this because of a lot of different reasons, none of which is a very serious issue in and of itself,” he says. “Technically, obviously it can be done. It can be made quite economical. There are regulatory issues, building code [issues], but those things can all be overcome.”

Whether out of concern for the environment or the bottom line, there is no doubt that the construction industry is showing an increased awareness of environmentally responsible building principles. In 2006, the Chicago-based Mintel International Group Ltd. estimated the green marketplace to be worth more than $200 billion. Chief executive officers (CEOs) are paying attention. According to a recent study conducted by PricewaterhouseCoopers, 61 percent of executives who responded said it was important that their companies take steps to reduce their environmental impact.

One organization helping companies do that is the U.S. Green Building Council, a nonprofit environmental organization that works with businesses to promote energy efficiency. Spokesperson Ashley Katz says that 39 percent of total energy consumption and 39 percent of harmful carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions come from buildings in metropolitan areas. The council helps companies reduce their energy use by showing them how to rely on windows instead of indoor lighting and how to install energy-saving air-conditioning units, among other techniques.

“I attribute it to a lot more awareness of climate change and global warming, whether it be Al Gore’s documentary [An Inconvenient Truth] or people learning more about the issue,” Katz says, “but I think right now this is a big time to be green, and people are really seeing that they need to step up to the plate in order to make a difference and turn back the clock on global warming.”

Show and prove

Kiss’ design has already saved the Coney Island Terminal both financially and in terms of CO2 emissions. And while architectural design that integrates photovoltaic technology could potentially help reduce electricity costs and harmful emissions across the country, Dr. Edward Kern of Irradiance, Inc. cautions that solar panel–integrated design is far from a quick fix for all of America’s power and pollution issues.

Kern has been working on the development and deployment of photovoltaic systems for close to three decades. A past president of the Solar Energy Business Association of New England, Kern and his company help to create commercial photovoltaic installations, and designed and executed many aspects of the Stillwell Terminal design.

Kern points to “incredible year-over-year growth” of 40 percent for companies that make solar cells as proof of the technology’s increasing acceptance. But he warns that it is best to take the development with measured enthusiasm, as the technology can reduce carbon emissions, but will not be able to completely replace the current means of producing electricity.

“It’s definitely a step in the right direction. The more solar you do, the better,” he says. “But it’s not something that’s going to end coal tomorrow and save the world.”

Kern points to the technology’s limitations, one of which is the finite amount of energy that panels can provide relative to an area’s electricity needs.

“If you look at the electricity consumed per square mile and the amount of sunlight falling on that square mile, for New York, that ratio … is a very large number compared to rural areas,” says Kern, adding that even if it were theoretically possible to put solar panels on every square mile of the city, “solar alone for New York isn’t going to do it. You’re going to have to bring in energy from the surrounding land.”

In addition to concerns about how much energy can be generated, Kern also believes that the other main obstacle to solar technology catching on in American cities is its cost-effectiveness. While solar cells cost about $4 a watt, coal, which he says is still the most commonly used fossil fuel, only costs “about $1 or $2” a watt. A power source’s dollars-per-watt ratio is determined by dividing the cost of the source by its rated energy output. For example, Kiss says that a panel that produces 200 watts and sells for $600 has a ratio of $3 a watt.

When solar panels first became commercialized in the 1950s, the cost was usually thousands of dollars for one watt, says Kiss. These days, prices are holding steady at $4 a watt, as booming demand for solar panels in Europe and Asia is keeping prices high at the moment, he says. But he’s encouraged by reports from solar technology developers First Solar, which is currently developing a thin-film photovoltaic cell that he says will be “approaching $1 a watt fairly soon.”

At that point, it’s unclear whether people will take to the change and how much energy solar panels will truly be able to provide, as even experts in the field cannot agree on just what can be reasonably expected of photovoltaic technology.

But it is clear that as proud as Kiss is of the energy saved by the terminal he designed, he thinks the greatest achievement he made at Coney Island was showing that large-scale, environmentally friendly, solar-powered buildings can not only be achieved, but can be practical and economically feasible.

“The general awareness of people that ‘yes, solar is great but it belongs in space,’ or ‘it’s going to be another generation,’ it’s just a lot of stuff like that adds up to a big obstacle,” Kiss says. “But there’s no inherent reason there shouldn’t be a lot more of this. And there will be — it’s just a question of time.”

Michael Tedder

Dear Reader,

In The Fray is a nonprofit staffed by volunteers. If you liked this piece, could you

please donate $10? If you want to help, you can also:

Seeking the zen of the present moment.

Seeking the zen of the present moment.