- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

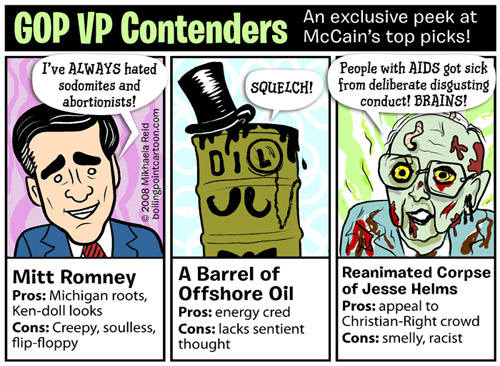

![]() VP Contenders.

VP Contenders.

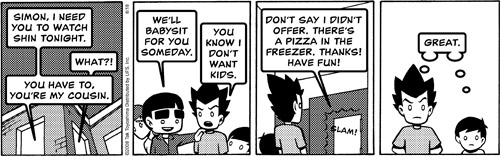

![]() Swing vote.

Swing vote.

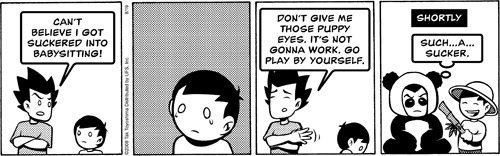

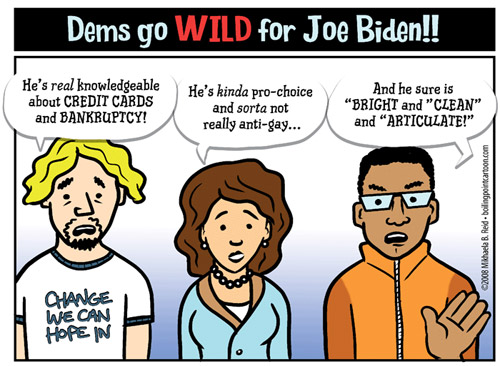

![]() Free ponies!

Free ponies!

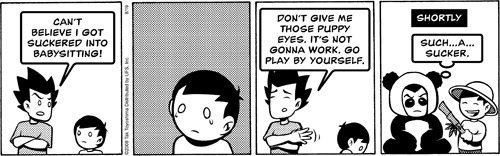

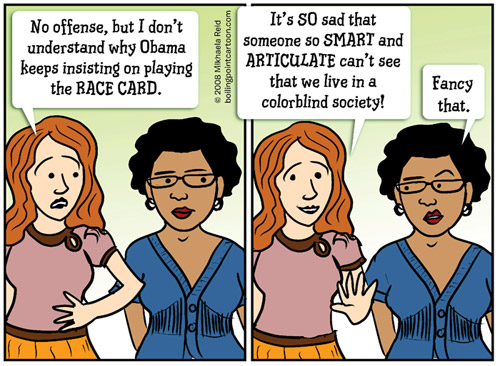

![]() Race card.

Race card.

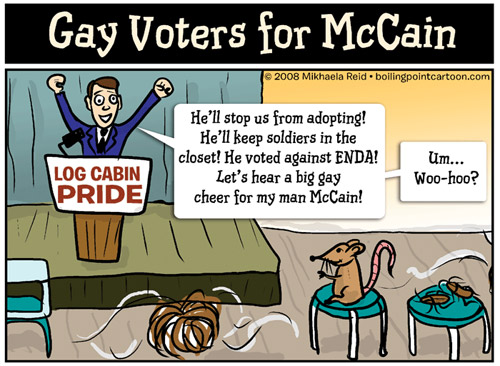

![]() Sqeeky clean.

Sqeeky clean.

[ Click here to view the visual essay ]

The history of humanity is a history of movement. As the first humans wandered out of Africa and began to spread across Europe and Asia, and then North America and South America, they became the world’s first immigrants. Just as with those who immigrate today, these mass migrations were made up of hundreds or thousands of individuals and families, each with their own story of how they uprooted themselves from their homes and ventured out into the unknown, encountering unfamiliar environments and searching for a better life. In this month’s issue, we feature a few of these personal stories of immigrants, refugees, and migrants.

Our journey begins with The jaunt, a story by Ashish Mehta about a journey with no obvious destination. Two people leave their home with nothing, one following the other, walking into the unknown with a purpose deeper than understanding.

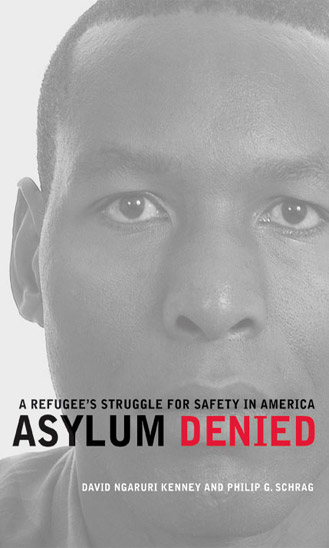

Like these two people, David Ngaruri Kenney left his home in Kenya for the unknown, fleeing persecution for a U.S. basketball scholarship. In A "little death penalty" case, Scott Kuhagen talks with Philip Schrag about Kenney’s legal struggle for political asylum in the United States.

The pressure to assimilate can weigh heavily on a new immigrant, but nostalgia about what’s been left behind can be stronger. In Feeding the need, Amy Brozio-Andrews reviews Broccoli and Other Tales of Food and Love by Lara Vapnyar, a book of short stories about how familiar food can assuage the loneliness of an unfamiliar country.

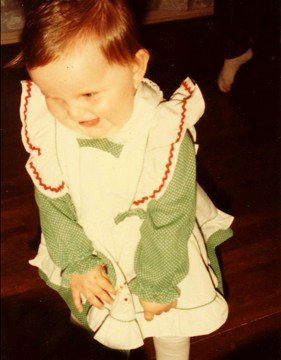

Immigrant communities can be another way to ease the pain of transition. Rose Symotiuk, who emigrated from Poland as a young child, grew up in the United States without this sense of community. In Notes from a "white immigrant", she writes of what it feels like to grow up as a "stealth foreigner": someone whose skin color doesn’t advertise her place of birth.

As immigrants settle, they gradually become residents, giving birth to children who call their adopted country home. Ties to the "old country" begin to fade as the generations progress, until eventually a family has little connection to its ancestral lands. Jane Varley, the great granddaughter of Lithuanian immigrants, writes in Where the moon is a hole in the sky of her encounter with her great grandparents’ homeland.

In Scenes from a party in Uganda, Jennifer Lee Johnson gets a taste of a newcomer’s cultural disorientation when she discovers that Ugandan relationships function in a very different manner than American relationships — and realizes that this isn’t a bad thing.

Finally, we turn to Adam Marksteiner, who brings us to San Lucas Tolimán, Guatemala for their Holy Week celebrations in his stunning visual essay Semana Santa.

The movement of people has shaped our world in the past and will continue to do so in the future. While those who leave are shaped by the country they move to, so too is their adoptive home shaped by the culture and traditions they bring with them. Far from diluting the dominant society, the culture immigrants bring with them rather enhances a country, bringing the spices, flavors, and ideas from another part of the world and adding them to the mix. It is this constant flow of people from one part of the world to the other that keeps culture vibrant and alive, a growing entity that is beautiful and strong.

Aaron Richner I am a writer/editor turned web developer. I've served as both Editor-in-chief and Technical Developer of In The Fray Magazine over the past 5 years. I am gainfully employed, writing, editing and developing on the web for a small private college in Duluth, MN. I enjoy both silence and heavy metal, John Milton and Stephen King, sunrise and sunset. Like all of us, I contain multitudes.

David Ngaruri Kenney, a farmer in Kenya, was imprisoned in a water-filled cell for organizing a protest. He applied for asylum in the United States and Philip Schrag, director of the Georgetown Center for Applied Legal Studies, worked on his case. They jointly wrote the recently published Asylum Denied: A Refugee’s Struggle for Safety in America, which recounts Kenney’s improbable trajectory from Kenyan farmer to U.S. college basketball player, and now, American lawyer.

Interviewer: Scott Kuhagen

Interviewee: Philip Schrag

What is the objective of the book and how did you get involved in Mr. Kenney’s case?

David Kenney was a political activist in his native Kenya in the early 1990s. He didn’t choose to become a political activist; he was a peasant farmer trying to grow tea and making a living. By doing so he discovered he couldn’t make a living growing tea because the price the government was paying was so low that it was causing him to lose money to grow tea. And yet the contract he had signed with the government monopoly prevented him from growing any other crops on his land.

So he organized a farmers’ boycott and protest to try to get the government to justify its policy or change it. And as a result, he was put in jail [and] nearly executed at gunpoint in a forest. He was saved at the last minute because the security forces of Kenya thought he could be more useful to the regime alive than dead. So they tortured him for a week, putting him in a water-filled cell in which he was in constant threat of being killed by drowning, and eventually put in solitary confinement for eight months.

When he was released from solitary confinement, his bank account was frozen and he was prohibited from meeting with more than three other Kenyans at the same time, so his life was effectively over. He had no commercial or social life, and could not even continue his education. He had an incredible piece of luck in that he met some American Peace Corps volunteers who had been assigned to his region, and they had the idea — since he was 7 feet tall — of getting him a basketball scholarship to the United States. This was pretty amazing because he had never seen a basketball! So this was a pretty far-out idea.

Nevertheless, they pursued it. They persuaded an American basketball coach to come from Colorado to Kenya to see him play basketball, and meanwhile frantically taught him how to play basketball.

He ended up coming to the United States on a basketball scholarship. He got a U.S. college degree, and when his education was over, Daniel arap Moi, who was in charge of Kenya when he was jailed and tortured, was still in power. So he applied for asylum. The book tells the story of his four-year struggle with our immigration services, in which he was constantly denied asylum by one bureaucracy after another, and eventually forced to go back to Africa, where he was nearly killed once again.

For those who might be unfamiliar with asylum, can you talk very generally about what an applicant would have to show [to win asylum]?

A person can apply for asylum if he has come to the United States either legally or without permission, and says that he is afraid to go back to his home country because of a fear of persecution on account of his race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group. Kenney of course was afraid to go back on account of persecution as a result of his political opinion.

If you apply for asylum, you get fingerprinted and photographed. Your identity is checked to make sure you’re not a terrorist. But more important than that, you are required to file hundreds of pages of corroborating evidence if you want to have a good chance of winning your case. It’s very difficult to obtain this corroborating evidence if you don’t have a lawyer working for you and if your friends and relatives back home are afraid that if they cooperate with you they themselves would get in trouble with the regime. This is a very challenging process for any asylum applicant, and most people who apply for it do not win asylum.

Is his experience with the system typical of the challenges that asylum seekers face?

Well, every case is different, of course.

Mr. Kenney, for example, was denied [asylum] by an immigration judge even though she believed that everything he said was true and he had a lot of documentation.

When he was halfway through his college education in 1997, he got a letter saying that his younger brother, a boy he had brought up as his own son after his father died, had been arrested and was being tortured in a Kenyan prison. And he knew very well what that meant.

So Mr. Kenney dropped everything, flew to Kenya, hired a lawyer, got his brother out of jail, and immediately returned to California to resume his studies. But because of this trip to rescue his brother, the immigration judge ruled that he had forfeited his status as refugee — that he was a legitimate refugee but he had returned home, proving that he was not eligible to be a refugee anymore.

His case went even further than that, correct?

Yes. He was represented at the initial stages of the case at the immigration court by students of mine at the clinic I run here at Georgetown Law School. It’s called the Center for Applied Legal Studies. The Center and clinics like it throughout the country have students who do all the work that lawyers would do, for academic credit, under the supervision of professors who are experienced lawyers.

And these students did a fabulous job of representing Mr. Kenney. One of them even made an impassioned closing statement at the trial, comparing his [Mr. Kenney’s] tea boycott with the Boston Tea Party of 1775, which did impress the judge despite the fact that she denied asylum. So they did a great job, but he lost there, he lost at the Board, and I took his case to the United States Court of Appeals.

Recently there have been some press reports, especially an article in the Washington Post that quotes the dean of Georgetown Law School, saying that interest in immigration law and immigration law clinics in general has really increased. As a clinical instructor yourself, what really excites you about this increasing interest in immigration law, and what are the hopes that you have for this new group of students moving into the field?

This field has just burgeoned in the last 20 years. In the early 1980s, there were virtually no courses in immigration law at most American law schools. It was a real backwater of legal education. Thanks to a small group of people who started popularizing this field long before I got into it, it is expanded, and now there are immigration law courses at most American law schools, and there are clinics in which students represent immigrants in real cases, as my students did in Kenney’s case.

Students find this area of law extremely exciting and interesting for several reasons. One is that they are little death penalty cases: there is a lot at stake! If a person wins asylum, they can apply for a green card after a year, and then start on the road to American citizenship. If they lose, they are ordered deported. If they are deported to their own country, which is the usual case, they may face imprisonment, torture, or death.

I was curious if you had any surprising or noteworthy examples where you’ve learned of how one of your clients who has received word that they can stay indefinitely in the United States has embraced their new country of the United States?

I think that the most dramatic instance of that occurred today! We recently won asylum for a young woman who had escaped from Zimbabwe — a political activist who had escaped from Zimbabwe — where you know that the human rights record, especially during the last election, has been very bad. She not only won asylum, but because she won asylum, she is able to bring her husband and children over to the United States, and everybody will be safe from retaliation and persecution. Well, she called our offices today and offered her services to volunteer to help other people in the clinic because she was so impressed with what the students had done to help her win her case.

Do you think that we are a generous and welcoming country, or do you have concerns in that area?

Our refugee law isn’t perfect. There are many blemishes and problems with it. But we’ve really come a long way since the 1920s and 1930s. Perhaps the most terrible incidence in American immigration history was when Hitler allowed 939 Jews to leave Germany in 1939. They thought that they could go to Cuba, but the Cuban president refused to let them in. The Christian captain of the ship then sailed the ship toward the United States, and off the coast of Florida radioed President Roosevelt and asked for permission to land his passengers in safety in the United States. And Roosevelt refused to let them land.

The ship went back to Europe, where nearly half the passengers, a little over half the passengers, were killed in the Holocaust.

We’ve come a very long way since then. In 1980, we passed a Refugee Act, and now we’re one of the most welcoming countries in the world at a time when other countries are again turning away refugees. We resettle a lot of people who are in need. Refugees are about 10 percent, maybe 15 percent if you include asylum winners, of all U.S. immigration. In 2006, we resettled about 40,000 refugees from United Nations camps around the world, and granted asylum to another 30,000 or so additional refugees. So that’s a pretty large number.

On the other hand, there are a lot of things we could do to make our system more fair. Perhaps the principal one, one of the first things that we should do is that we should enable people to get fair representation in asylum proceedings when they are indigent. The chance of winning asylum without a lawyer or a representative is 16 percent in immigration court.

With a lawyer — all lawyers combined — it’s about 41 percent. With a lawyer from a law school clinic or a nongovernmental organization [NGO] such as the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society or Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service, or a pro bono lawyer from one of the large law firms, the chance of winning asylum in immigration court is about 90 percent. Not because these organizations select the cases more carefully than others, and not because they’re more brilliant than the other lawyers who represent asylum seekers, but because lawyers from big law firms and NGOs limit their caseloads and devote enormous amounts of resources to investigating the facts of each case, getting all that documentation to prove the case so that the judge doesn’t just have to accept the asylum applicant’s word for it.

Unfortunately, there aren’t enough such lawyers to go around, so providing free legal representation to indigent asylum seekers is essential for fairness in our system.

[Without giving away the ending] what is the outcome of the case and your relationship with Mr. Kenney?

Mr. Kenney, despite being nearly killed three times in his life, is currently back in the United States. He is a lawful permanent resident and has applied for American citizenship. He has graduated from an American law school, Catholic University Law School, and is working in the district attorney’s office of Montgomery County, Maryland. So it’s been an extraordinary odyssey for him from being a peasant farmer, to being a political prisoner, to being a student at an American college, to being ordered deported and leaving the United States and being nearly killed in Africa again, to coming back to the United States and graduating from law school here. During that period, I have been fortunate enough to become his friend and his co-author.

I’m a white American, so I suppose that immediately means I have this great white privilege, like I got a VIP card in the mail or something. Let me say, to start, that I absolutely believe that racism is still around. Institutionalized racism and white privilege are both very real in modern American society. I’m not denying that at all.

I’m uncomfortable being associated with white privilege, because I wasn’t born here. In fact, I’m a refugee.

I came from Poland to America as a baby. In my early days, we lived in Section 8 housing and my mother worked at a Kmart in the ghetto. It was I who taught my mother how to drive: Along with English, driving really stumped her. I had to learn the fundamentals from our teacher in English and then drive around yelling “CLUTCH!” in Polish. I also translated for my grandma when she lived with us. We went to refugee groups with the Vietnamese, and attended “poor” family activities at the YMCA.

At about seven years old, I remember riding the bus with my mother with an incredible tension inside me. My mother had taken the civil service exam and aced it. Having studied half a dozen languages growing up, she found written English far easier than spoken. Now she was going to find out if she had landed a job at the post office. In our home country she had a job as a newspaper editor, and now our only salvation was the post office.

She got it and has worked there for over 20 years now. The reliable pay and good benefits of that government job slowly pulled us out of our lives as poor immigrants. I went to Catholic school, where I was ostracized for my Nutella “chocolate sandwiches” and thrift store clothes. She eventually pushed me to go to a “fancy” private university, where I felt very out-of-place among the 98 percent very rich, very white population. I hung out with the poor kids on scholarship like me. My best friends were a black woman from Atlanta and a redneck from Mississippi.

I was hurt when my black friend started hanging out with the girls in the black sorority. They and the other minority students in my junior high and high schools got to bond in their ethnic clubs once a month.

From kindergarten through 12th grade, we spent half a year reading black history books and researching the Holocaust. To this day, I’ve only met two other Eastern European refugees. I’ve never learned in school about what happened to me and my family.

I’m white, right? I get a passing grade if not privilege.

As an adult, my skin color has allowed me to drop almost all issues of being an immigrant and of being poor, within a matter of years. I do get it: Fat people get hassled in grocery stores and restaurants because they can’t hide their weight. Black people get turned down for loans and jobs because they can’t hide their skin color. Fourth-generation Americans get pulled over by airport security for “looking like” terrorists. My Asian friends, despite saying they are from America or Canada, get asked, “But where are you from originally?”

By contrast, I tell people I wasn’t born here and “that’s right, I’m a stealth foreigner, here to take your jobs.” Sure, there’s no big “FOREIGNER” stamp on my forehead, but sometimes I want to share in that struggle with my fellow “underclass.” That’s why I live in Harlem and eat in Greenpoint.

I feel as if I spent my childhood with all the poor immigrants and at some point in my teens someone ran in and said, “Wait! Dear God, what’s a trustworthy, white American girl doing mixed in with these people?”

There are snobby, rich people in every country, but I always found it somewhat sweet that so many wealthy people in the United States are completely egalitarian. Even as they earn six figures, most “middle-class” friends of my mother and me are quick to defend the fact that they work, have only part-time cleaning services, and that their kids’ cars are used.

My fiancé’s family is fairly well-off, though I suppose they’re still middle-class by American standards. They’ve only had positive things to say about my family’s early struggles, and openly embrace the color I bring to their lives. I imagine it is taboo in their culture to consider themselves above people like me.

Still, the other day we were driving through Connecticut, and I mentioned that my cousin lived and worked there.

“Illegally?” my fiancé asked, and I murmured an affirmative. There was no judgment, just surprise. Just a bit of weight in the air between us, as my other life — the life of a poor refugee — drifted into the car and sat between us. It left quickly though.

We were a nice white couple driving through Connecticut, after all.

“How is it that you do not have any children, Jennifer?”

I thought about it for a second, bewildered. It was a question I’d never been asked before, considering that I was 27 and not yet married. Then again, this was the first time that I’d made polite conversation at a party in Uganda, a country where most women are married by age 17 and the average woman has seven kids.

I visited Uganda last December to attend meetings for a reproductive health network in East Africa as part of my work for a Washington, D.C. nonprofit that advocates for women’s reproductive health issues. It was my first time in Africa and only my second time abroad, so to say that I wasn’t sure what to expect was the understatement of the century. I imagined exploring local villages, visiting health clinics, and meeting the people that my organization supported. Instead, it was day four and all I’d seen was the over-air-conditioned conference room of my hotel, where I’d sat in all-day meetings discussing policy with regional officials. Not exactly the eye-opening experience I’d been expecting. A conference room is a conference room, no matter what part of the world it’s in.

But things were looking up now that I’d finally been let out of the hotel. Our meetings were over; I still had three days in Kampala ahead of me, and our Ugandan hosts were throwing a party to celebrate all our hard work. In the United States, business meetings end with a handshake and the mutual signing of contracts; in East Africa, they end with a party, complete with a DJ, an open bar, and dancing. In another stark contrast to American business practices, the guests at this party actually let loose and had a good time. This was no stuffy affair filled with empty speeches and pretense; this party was truly an opportunity to break out of the rigid formality of our meetings and “get to know each other as brothers and sisters,” as one of the group’s leaders explained it. It looked like I was finally about to learn more about the country that I’d flown halfway around the world to experience.

We were still in a hotel, but this one was a little more inviting than the one I was staying in. The party was in a third-floor party room, complete with a beautiful veranda overlooking a garden. Brilliant fuchsia blossoms bloomed from vines twisting around the veranda’s railing, and you could hear the steady hum of insects mingling with the distant roar of Kampala’s ever-present traffic jam. We all converged at the veranda’s bar, tipping back our heads to drink to the success of our meetings.

Throwing myself headfirst into the festivities, I started chatting with a group of young government officials who were more than eager to tell me more about life in Uganda. Twenty minutes later, I somehow got caught up in a conversation about the state of my fertility with Joseph, a short Ugandan man with piercing brown eyes and a boyish grin. I told him I was getting married in April and that I was waiting to have children until I was ready. “I guess America is different,” I said. “A lot of American women like to wait until we’ve experienced life and had a career before we get married and start a family.”

Joseph was incredulous. He shook his head slowly, convinced that I was putting a happy face on my clear failures as a woman. He looked so sad for me that I started trying to convince him that I really was happy. How did I get to the point in my life where I had to defend my life decisions to a guy at a party in Kampala? “So, how many kids do you have?” I asked playfully, trying to turn the conversation back to him.

“Only five. Three girls and two boys.”

“Only five? Sounds like a lot to me.” I was pretty sure that Joseph was younger than I was. How did he have five kids already?

“Is not so many, my brother has eight. I have to catch up!” Joseph wasn’t joking.

“So, who is taking care of them right now?” (It was 10 o’clock on a Wednesday night.)

“They are with their mothers.” Mothers. Slowly I teased out of him that he was married, but also had kids with a mistress. Not only that: He spent a few nights a week going out dancing and drinking without his wife, but not without female companionship, if you catch my drift.

I made the joke that if my fiancé did that, he wouldn’t be my fiancé anymore. “Why not?” he asked. Joseph was genuinely bewildered. The other people in our little group all stared at me like I was crazy. I was starting to feel like a judgmental prude.

“What is wrong with going out?” one woman asked me, curiously.

Good question. What was wrong with “going out” if both parties involved are okay with it? I’d read about infidelity in Ugandan culture and always imagined that it was the men who were “at fault” and the women were victims. Could it be that women were just as likely to be cheating? Was it really cheating, or did relationships just work differently here?

And that was when I realized that throughout our entire conversation, I’d been judging Joseph based on my American perceptions of how a relationship between a man and a woman should be. Now, I don’t know what Joseph’s wife thought about his infidelity, or if she even knew about it, but after talking to a dozen different people of both genders at this party, I did know that Ugandans had a very different stance on infidelity. And these were the people who worked in reproductive health, the people who know that having multiple concurrent partners raises the risk of contracting a sexually transmitted disease and who had devoted their careers to educating their peers of this fact.

By assuming that a woman should be offended (if not incensed) by her partner’s infidelity, I was viewing Joseph’s relationship through a lens tinted with my own cultural biases. Even worse, it was keeping me from really understanding what it was like to live in Kampala, which was the whole point of my trip.

I felt like the people I hated: Americans who travel abroad and then spend the entire time limiting their experience to fit preconceived notions of how things should be, rather than opening their minds to new adventures, new friendships, and a greater understanding of the world. Traveling in a self-contained bubble isn’t any different from staying home; by filtering your experiences, you aren’t really experiencing anything.

So I smiled and said, “Nothing’s wrong with going out, it’s between you and your wife.” The group of us then took a shot of what Joseph called Ugandan Orange, a very strong whiskey-like liquor distilled from oranges, and I left the rest of my preconceptions at the bar. The music started pumping loudly from the dance floor — it’s not an African party if there isn’t dancing, I learned — and we all hit the dance floor, singing along to Madonna’s “Holiday.” (Knowing all the words made me quite the popular dance partner!) We stood in a circle, teaching each other dance moves and laughing the night away, forgetting the ways we were different and relaxing into our new friendships, all to an ’80s pop soundtrack.

In one night of drinking and dancing in Kampala, I learned more about what it was like to live there than I did during the entire first half of my trip. More importantly, by shedding some of my preconceived notions, I was able to view the rest of my trip through the eyes of Joseph and my other new friends, opening myself to really learning about the country and its people.

I might not have been in what my new friends would have called a happy “relationship,” but the men and women I danced with that night sure were. After all, who am I to judge? I’m 27 and I don’t even have any children yet!