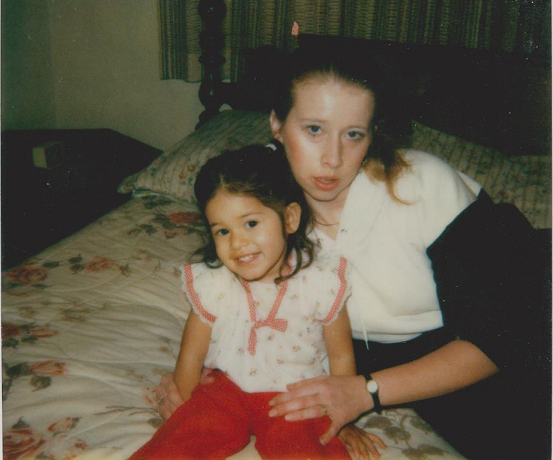

She looks like a child: a baby face and large, round eyes, long and thin arms that make her seem gawky. When she sees me, her eyes brighten, and she struggles to sit up in her hospital bed. The blanket covering her drops, revealing a frail and gaunt body—a nineteen-year-old’s body. Five feet, four inches, she weighs only eighty pounds.

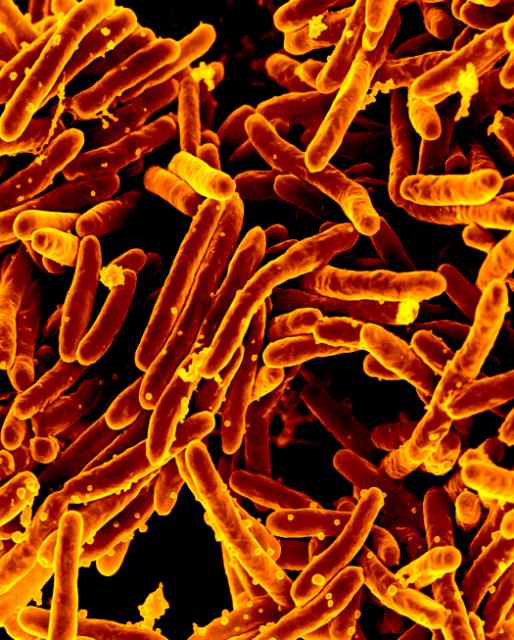

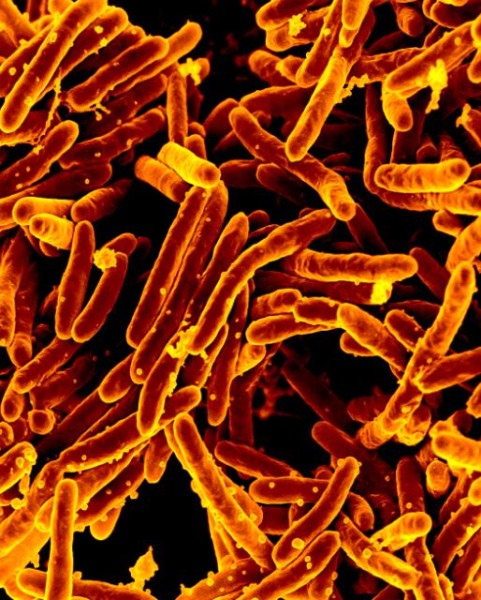

Sonam Yambhare is dying, and there is little modern medicine can do for her. Two years ago, she contracted a drug-resistant form of tuberculosis in her lungs. The bacteria that cause the disease have destroyed her macrophages, the body’s first defenders against foreign invasion. Constant nausea, loss of appetite, and vomiting—symptoms of the disease—have emaciated her. All medications have been infective. In her weakened state, another serious infection will likely kill her.

Ward Number Eight of the Sewri Tuberculosis Hospital is a silent room with gray concrete walls. It is a world away from the chaotic streets of Mumbai. And it is a world away from the rest of Indian society. With nowhere else to go, neglected and stigmatized TB patients like Yambhare come here—even from towns and villages hundreds of miles away—to wait out the last stages of the disease, sometimes alone.

“Everyone is depressed here,” says Chandge Mokshada, a young doctor on her rounds. In the crumbling ward, dozens of women lay quietly on their beds. There is little chance they will recover, Mokshada says. “We mostly lose our patients.”

One of the world’s most lethal infectious diseases is making a comeback. Two centuries ago, tuberculosis was responsible for a quarter of all deaths in parts of Europe and the US. Known as the “white plague” or “white death” due to the way it blanched the skin, the disease left a deep imprint on the culture. Thomas Mann and Fyodor Dostoevsky wrote about it. Emily Brontë and Henry David Thoreau died from it.

After the development of effective antibiotics in the 1940s, deaths from tuberculosis plummeted. But TB remains a formidable killer in many parts of the world. And in recent years, it has evolved in frightening ways. Its virulent new strains now defy many or all known antibiotics. And while they have ravaged Asian countries in particular, these deadlier forms of the disease are spreading everywhere.

Last month, the World Health Organization released a report about the surge in infectious diseases that are fast becoming untreatable. “A post-antibiotic era—in which common infections and minor injuries can kill—is a very real possibility for the 21st century,“ the report read. The WHO singled out drug-resistant tuberculosis as one of the greatest dangers. In 2012, it accounted for 450,000 new cases and 170,000 deaths—that is, less than 4 percent of those newly infected with TB, but 13 percent of those the disease killed. The total number of confirmed cases has grown sevenfold over seven years, with India, China, and Russia accounting for more than half of new infections. (The official statistics also understate the size of the problem, since many of the hardest-hit countries report bogus numbers.)

New strains of TB arise when the old ones are not properly treated. Not taking a full course of antibiotics, for example, can merely weaken, rather than eradicate, the bacteria that cause the disease. The remaining bacteria evolve to adapt to the drug, turning a treatable strain of TB into a resistant one.

The problem has gotten progressively worse. At one point, health officials believed TB could be eliminated. But in the 1980s, tuberculosis strains emerged that resisted the most common and safe anti-TB drugs. In the past decade, even second-line treatments have become ineffective against certain tough strains that fall under the category of “extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis” (about 10 percent of drug-resistant TB cases). To deal with them, doctors will put patients on more than one of these toxic drugs. Their side effects, however, can be severe, ranging from acne, weight loss, and skin discoloration to hepatitis, depression, and hallucinations.

For the hardest-to-treat strains, doctors are now forced to use so-called third-line drugs, an even more toxic regimen whose effects have yet to be fully tested.

Today, resistant strains can be found virtually everywhere, including the United States and Europe. But perhaps nowhere is the crisis more real than in India. The world’s second most populous country has a quarter of its TB cases—and now, many of the hardest ones to treat. While the number of Indians suffering from the disease has actually gone down in recent years, thanks in part to widespread vaccination, the WHO estimates that in 2012 the country had 21,000 new cases of drug-resistant TB of the lungs—an exponential increase from the few dozen cases the government had been reporting just six years earlier.

India also has the dubious distinction of being one of three countries—Iran and Italy being the others—where certain strains of TB have resisted every drug used against them. Four years ago, Zarir Udwadia, a noted pulmonologist at Mumbai’s Hinduja Hospital, identified twelve patients suffering from untreatable TB infections. (Three of the twelve have since died; the others have been taken into isolation by the government.) Udwadia and other researchers have described these kinds of cases as “totally drug-resistant.”

The Indian government disputes the categorization, arguing that these strains have not been tested against all of the experimental third-line drugs. Another term, “extremely drug-resistant TB,” gets around the worry of some experts that classifying such a common disease as untreatable may cause panic.

Regardless of what they are called, these hardy strains have the power to push societies back to a time before antibiotics, when the “white plague” was all but unstoppable. “If not contained,” says infectious disease specialist Charles Chiu of the University of California, San Francisco, “it poses a big problem to the world.”

In India, those infected with TB tend to be the most vulnerable people in society. Yambhare was born into a low caste. She lived in a cramped apartment, where she shared a room with her mother and two sisters. Every day she took overcrowded trains from her home in the countryside to Mumbai, where she helped her mother clean houses. In other words, her poverty made it far more likely that she would be exposed to TB, which often (though not always) settles in the lungs and can be transmitted through the air.

Two years ago, Yambhare developed a persistent cough. She visited one of the private medical clinics that line the teeming streets of the western suburb of Bandra. There, a doctor diagnosed her with tuberculosis, and Yambhare began taking antibiotics. When her family saw no improvement over two years, they switched doctors. The new doctor prescribed more drugs.

No one bothered to give her a drug-sensitivity test. The test would have revealed what strain of TB she had, and a competent doctor could have then prescribed the correct drug. Instead, the incomplete and inept treatment that Yambhare received gave the bacteria the chance to adapt and become stronger. It soon developed a resistance to all four of the first-line drugs used to treat TB.

In Yambhare’s case and thousands of others, a broken health-care system has made the problem of drug-resistant TB much worse. Hospitals are overcrowded, and the services provided are minimal. So Indians—rich and poor—flock to private doctors. But the slapdash treatment they tend to provide, with laxly administered drugs and inadequate follow-up care, has allowed drug-resistant TB to spread wildly.

Udwadia, the Mumbai pulmonologist, says that many of these doctors are unscrupulous, and most are uninformed. In 2010, he conducted a study in Mumbai’s Dharavi slum, one of Asia’s largest and the origin of many of the city’s most severe TB cases. He asked more than a hundred doctors in the area to “write a prescription for a common TB patient.” Only six were able to do it correctly. Half of the doctors he surveyed were practitioners of alternative therapies with no grounding in modern science.

Udwadia argues that India needs a law that will let only designated specialists treat drug-resistant tuberculosis patients. But at the moment the government does not bother keeping detailed records on the many private doctors now operating, much less ensuring they provide adequate care.

“The government has no control over private practitioners,” says an official in the health ministry, speaking on condition of anonymity since he is not authorized to talk to the media. “They require only once-in-a-lifetime registration, and there is no chance for them to lose their license.”

Calls for regulation by experts like Udwadia, the official says, are silenced, ridiculed, or ignored. Meanwhile, the government has been accused of underreporting the number of new cases of drug-resistant TB every year. In 2011 the official count was 4,200 cases; the next year, the government began adjusting its figures to resemble the WHO’s estimates, and the number of reported cases quadrupled. (Indian health ministry officials did not respond to emails asking for comment.)

In terms of its anti-TB spending, however, the government has been devoting more resources. In 2013 it budgeted $182 million to fight the epidemic.

Some of this money will go toward upgrading the 103-year-old Sewri hospital, which could use it. In its ward for drug-resistant patients, there is no medical equipment in sight; records are kept in rusted metal cabinets. The most pernicious forms of TB are hitting a health-care infrastructure poorly equipped to deal with them.

Every year, more than eight million people fall ill with tuberculosis. More than a million die from it, placing TB just a notch below AIDS in its globe-spanning lethality. And a whopping one-third of the world’s population has what is called “latent TB”: they are infected by the bacteria, and a tenth of them will go on to develop the disease at some point in their lifetimes. Drug-resistant TB, in other words, is just one part of a global health emergency.

Meanwhile, the problem goes ignored in rich countries. Antibiotic treatments for TB have been so successful there that most people’s experience with the disease today is limited to works of literature: novels and poems with archaic references to “consumption” and TB sanatoriums. But that may change someday soon. In the United States, a hundred new cases of drug-resistant TB are diagnosed every year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cases of extensively drug-resistant TB have already been reported.

Paul Nunn, the WHO’s TB coordinator, says that these deadly strains have cropped up in certain European countries, too, though the reports have yet to be published. “If the health system of the world fails, the highly resistant strains will replace the old,” he adds. “We’ll see a worsening of the situation if nothing is done.” On the other hand, it may be only when the resistant strains become a major problem in rich countries that the profit-seeking pharmaceutical industry will take notice and pour real money into the development of potent new treatments.

Without effective drugs to combat the most resistant strains, doctors may have to revert to remedies from an earlier era. Udwadia recalls his first patient with untreatable TB. Twenty-six years old, she had spent the last five years trying a variety of anti-TB drugs, all of which had failed. As a last resort, she underwent a pneumonectomy, a high-risk medical procedure to remove a lung. The woman later died of complications from the surgery. The procedure had not been used on tuberculosis patients since the introduction of antibiotic treatments six decades ago.

Even though so many people are infected, TB still carries a terrible stigma in Indian culture. “People treat you with disgust,” Yambhare says. As she grew sicker, she became more isolated. Her sisters were told to stay away. Her friends stopped visiting. Finding a partner or even a job was impossible. She sunk into a depression.

Meanwhile, her family struggled to pay for her treatment. Their monthly household income was just $100—not uncommon in a country where one in three people lives on less than $1.25 a day. But the expensive second-line drugs cost $80 a month. And once she began taking them, the side effects kicked in. Her skin became discolored. Her muscles atrophied. Her weight dropped.

Eventually, Yambhare’s family could no longer care for her. They sent her to the Sewri hospital.

When I visit her in the ward, orderlies are carrying out the infected mattresses of previous patients. In a nearby courtyard, they set the mattresses afire.

Yambhare watches the smoke curl past the window near her bed. Below her, in the courtyard, stray dogs fight over bones.

Yambhare turns to me, an eerie shine in her eyes. “I don’t want to die,” she says through her mask. “I want to go home and help mother.”

Octavio Raygoza is a video journalist who covers sports, news, and culture. Twitter: @olraygoza

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content