Perhaps the most consequential single episode in the recent history of the northern Mexican city known as the Laguna occurred on May 13, 2007. On that sunny Sunday afternoon, local political heavyweight and underworld boss Don Carlos Herrera and his wife were on their way back from a trip to the local Sam’s Club when their armored car was intercepted by an armed unit. The assailants riddled the car with more than 100 rounds.

Like hurricanes, armored cars are measured on a scale from one to five, with level-five armor offering the greatest capacity to repel projectiles. Herrera’s Cadillac Escalade was a level four, but the bullets, which had never before been seen in the Laguna, blew right through it.

Both Herrera and his wife suffered bullet wounds, and they were raced to a nearby hospital. Scores of local police maintained a one-block perimeter around the area, with no unauthorized person allowed to come any closer. Herrera and his wife survived, but Herrera’s longstanding control over the local drug trade was no longer undisputed. The battle for the Laguna had begun.

Carlos Castañeda is a stocky man in his late 20s, with a shaved head and a wide, welcoming face. He’s worked as a reporter in the Laguna since he graduated from college in early 2000, which he says was the fulfillment of a long-held dream.

“I always wanted to work for a media outlet. As far back as I remember, that’s what I wanted to do. It seemed like the most interesting career. My family wanted me to study some other major, engineering, something that paid a little better. But no, it wasn’t what caught my interest.”

The city where Castañeda works is actually made up of several cities: the Laguna is the colloquial name given to the neighboring municipalities of Torreón, Matamoros, Gómez Palacio, and Lerdo. With more than a million inhabitants, it is the ninth-largest metro area in the nation. Its economy (based largely on exports), quality of life (relatively high), and weather (hot as can be for 10 months of the year, bone chilling for two) make it a typical northern Mexican metropolis.

When I first moved here in 2005, the tranquility of the city and the trustworthiness of its inhabitants were among its foremost traits. While neighboring regions suffered under the weight of surging drug-related violence, the Laguna was an oasis of calm, an unlikely “Pleasantville” just south of the border region. You could walk around late at night undisturbed. Physical violence didn’t go beyond bar fights. Sightings of machine gun–toting federal police and army troops were limited to the television.

In May 2007, Castañeda was a relatively new reporter to the crime beat at La I, a local tabloid newspaper with a penchant for splashy photos and direct, pithy headlines. At that point, Castañeda’s reports revolved mostly around drunk driving accidents. As luck (or more precisely, his schedule) would have it, Castañeda was not working the day Herrera was attacked. But an event of such significance prompted a phone call from his editor, and when he went to work on Monday, he began following the story. This meant little more than the mundane task of tracking Herrera’s physical improvement in the hospital, but the broader significance of the event would soon be known.

The attempted assassination of Herrera was the opening shot in what has turned out to be a very long battle for control of the city. The drug gang known as the Zetas — founded by ex-military officers and linked to traffickers in the Gulf state of Tamaulipas — had moved into town and was determined to rip control of the Laguna from Herrera and his backers in the Pacific state of Sinaloa. At stake were both valuable smuggling routes (Torreón is just six and eight hours, respectively, from key border crossings in Nuevo Laredo and Juárez) as well as the growing local drug market.

What followed was a string of recriminations, kidnappings, threats, grenade attacks, and killings that carry on to this day. In the days following the attack on Herrera, the leader of the region’s anti-kidnapping unit, Enrique Ruiz, was himself kidnapped; his captors videotaped their blindfolded victim identifying local businessmen as being in a league with Herrera.

As Ricardo Ravelo narrates in his book Chronicles of Blood, the Zetas then arranged for the video to be shown before a reunion of a local business group, many of whose members were implicated by Ruiz. A letter was read to the gathering, which warned, “The person who has illicit business outside of our organization will be bothered … be informed that any disobedience before our petition will bring irreversible consequences for yourself and your business partners.” According to Ravelo, 25 private aircraft left the area for the United States the following day.

Today, more than two years later, incidents worthy of an action film are regular occurrences. The city awakens to the sight of executed bodies on a near daily basis.

Last summer, an armed group attacked the police station in Lerdo in broad daylight, killing four officers and beating up female employees before fleeing. (The chief resigned shortly thereafter.)

In September of 2008, Torreón received national news coverage when the army arrested several dozen of its local police for working for the Zetas. Torreón celebrated Christmas Eve with a gun fight in the midst of a downtown shopping rush, and rang in the new year with a nationally televised, four-hour firefight that caused the evacuation of the city’s toniest neighborhood. Schools around the region closed days early, ahead of the 2008 Christmas holidays, due to rumors that armed groups were planning to force their way into the schools to rob all the teachers of their Christmas bonuses (worth two weeks of salary). It’s as if the various cities making up the Laguna are competing for the most sensational headline.

For Castañeda, all this has meant navigating a city that was far different than the Laguna in which he had grown up. A common trope about the drug wars in Mexico is that the drug gangs only kill each other. There’s an element of truth to that, but the underworld fighting invaded the daily routines of the Laguna as a whole. The Zetas created a climate of fear that extended well beyond those who make their living smuggling cocaine, marijuana, and the like northward. They supplemented their trafficking income with car theft, kidnapping, and extortion, all of these crimes much more of a public menace than the peaceful passage of drugs. Other criminal groups, dedicated to many of the same activities, took advantage of the chaotic backdrop to establish a toehold in the Laguna underworld.

The press was among the casualties. Castañeda talks about a local press corps that was threatened and bullied. Various newspapers and television stations were threatened as well. One reporter in Gómez Palacio was kidnapped and beaten up in response to something he wrote, but Castañeda said the threat to the local press went far beyond one mere incident.

“More than a direct threat against any reporter in particular, what you see is a change in the climate in which the reporters work,” Castañeda says. “The editorial chiefs say to be careful, to not investigate too much.”

“[You write] what the authority tells you, no more. Don’t search for more, don’t ask, don’t investigate, period. This is the problem, the self-censorship that has taken hold in the media outlets, which definitely goes hand in hand with the fact that it has gotten more dangerous. That’s how the reporters see it.”

Reporters in the Laguna have reason to be concerned. Mexico is one of the most dangerous places on the planet for a reporter, with more than two dozen journalists killed since 2000, and a handful more who have disappeared. Both Reporters Without Borders and the Committee to Protect Journalists rank Mexico as the most dangerous country in the Western Hemisphere to work as a reporter. From the federal government down, official efforts to address the problem have been slow and ineffectual.

Castañeda says the impact of the threats is palpable. “These threats, whether they are real or not, have modified the way the coverage is carried out.” In response, some newspapers also removed authors’ bylines from crime stories and had local police stationed at the entries to the offices throughout the workday. Media outlets also coordinated their coverage, so that no one newspaper or TV station stood out too much.

Castañeda adds: “Between the media outlets, there’s a discussion among the editorial bosses, the directors, when there’s a story about a murder, and execution — any of that — it’s treated with official information, with information sent by the procuduría, and since then, nothing has been investigated. Nothing is published beyond that which is official information. Information that the authorities provide. There’s no way to balance this information. So as to not get us in trouble, to not investigate too much, to not receive threats, to not be singled out, to not provoke these powers — the drug traffickers — we’re going to go with official information.”

At the same time, the basic obligations of the job hadn’t changed, which left people like Castañeda walking an increasingly fine line. “The reporters have to be playing two games — with the company for whom they work, and with the authority. And with the organized crime, too.”

“Now the officials are so scared, that they say, ‘Don’t put me in the news. Don’t interview me, please.’ It’s really tricky, the situation now. Before, the same functionaries would call you and tell you, ‘I have a detainee here, it’s interesting’ … The authorities themselves feel threatened.”

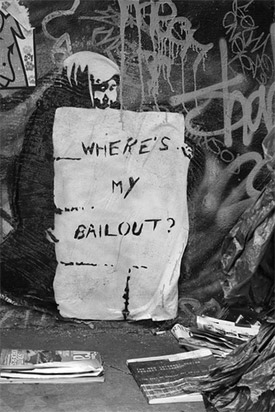

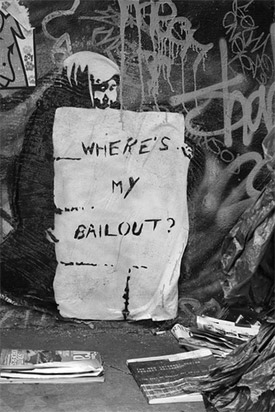

The vacuum that the threatened media left behind ceded space for the dissemination of news through other, less formal means. Alarming, and often brutally graphic, email chains spread news of assassinations, as well as warnings of upcoming violence.

Incidents like those described above were accompanied by the daily dissemination of fear-mongering email chains. Most, written by a concerned citizen or someone pretending to be one, warned against imminent bloodbaths at some bar or another: “So I ask you to please listen it’s for your good don’t go out to bars in the night and if you see trucks without plates report them. In Lerdo be careful in San Isidro and Back Stage. Gómez: In Flamingo’s and Tonic. Torreón: K-pital and La Quinta bar.”

Other emails claimed to be the voice of one trafficking group or another, and tried to justify their presence while condemning their competitors: “[W]e DON’T KIDNAP, NOR ROB, NOR DO WE HARM INNOCENT PEOPLE, we ask that you don’t get scared with big-talking assholes that act with impunity because they are protected …”

Still others served no communicative purpose other than to terrorize. I once received an email that was just a series of snapshots of severed heads in a convenience store, all with a bloody “Z” carved below the hairline.

The impact of the rising tide of drug-related violence in Mexico has extended far beyond one mayoral administration or a small coterie of business big shots. The Laguna has seen the organic weakening of society, from top to bottom. Mexico City columnist Ricardo Raphael captured the prevailing sense of chaos during an August 2008 column:

“Until a little while ago, the Mexicans from the Laguna were famous for being big spenders and big partyers … Now, nevertheless, the streets of the Laguna empty out at eight o’clock at night and consumption has plummeted. The war against drug trafficking has dramatically affected the lives of these residents. As in Tijuana, Juárez, or Culiacán, here also fear has gained ground.”

The same day that Raphael’s column ran, a heavily armed military convoy — totaling 350 ski-masked soldiers and more than 50 Hummers and troop transports — drew stares while proceeding down Torreón’s main drag. A dozen police patrol trucks accompanied the soldiers, a handful of jackals escorting a pack of lions. The soldiers reassured the inhabitants that there was an official authority more powerful than any drug gang, but violence didn’t drop. Indeed, it continued to rise.

Just before the new year, Castañeda switched off the crime beat. Like the ex-police chief in Lerdo, he cited stress as a reason for the switch. Since his professional interest is based less on covering crime than in reporting generally, it has been an easy adjustment. Now he writes international and national news summaries, studies English in his spare time, and freelances at a new magazine called Magdalenas, which focuses on sexuality in the Laguna.

Mexico as a whole saw a drop of 26 percent in drug-related killings in the first three months of 2009. Some of the biggest drops were in Tijuana (79 percent), Juárez (39 percent), and Culiacán (45 percent) — the same trio of perennially drug-addled cities mentioned by Raphael.

Unfortunately, the Laguna largely missed out on this hopeful trend. More than 120 people were killed from January to March, which would give the Laguna a murder rate greater than any in the United States. In one night in February, 11 people were killed in firefights around the city.

In mid-May, a reporter from La Opinión, one of the two major dailies in the Laguna, was abducted and murdered. He was the first reporter to be killed for his work in the city. In its influential Bajo Reserva editorial column, Mexico City’s most prominent newspaper, El Universal, had the following reaction:

“They tell us that in the Laguna things are very, very dangerous for the press, and for society in general. Two groups are fighting for the city: Zetas and ‘the ones from the house on the hill.’ The former are locals. They tell that the two groups continue giving forced conferences to the press. Be careful. The Laguna is coming apart; some say it could be the next Juárez.”

The civilian population, from the mayor’s office, to the press, to the burrito vendors, remains cowed. The reporters who are able, find safer topics than crime to write about.

Patrick Corcoran

Dear Reader,

In The Fray is a nonprofit staffed by volunteers. If you liked this piece, could you

please donate $10? If you want to help, you can also: