- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

Worshippers kneel on pine needles in front of open Coke bottles and melting candles. Colored ribbons hanging from pointed straw hats cover their faces. Faded wooden saints wearing silk stare from behind glass cases. Clouds of incense muffle the chants of the Tzotzil villagers in San Juan Chamula Chiapas, as busloads of Europeans wear a path in the tile. The tourists outnumber the locals, but they have come to witness the religious ceremonies of indigenous Mexicans.

Who are these “indigenous people” of Latin America, and what does it mean to be an Indian? Few countries in Latin America have tribal registries based on bloodline, and most do not have established reservations. Is the answer in the way people dress, the language they speak, the religion they practice, or the color of their skin? Is it valid to fear that indigenous ways of life are vanishing?

These questions are hard to answer, but need to be explored.

The lines that once separated the “indigenous” from the “Latins” are blurring. Hundreds of years ago, the Spaniards came to key cities of economic and geographic importance. They rarely ventured out of these established areas, allowing indigenous communities to develop in relative isolation. Today, however, cultural isolation is rare. As transportation continues to improve, migration occurs and languages disappear; cultures merge. Now only the extremes are obviously identifiable as “white” or “indigenous.” The majority lie somewhere in the middle.

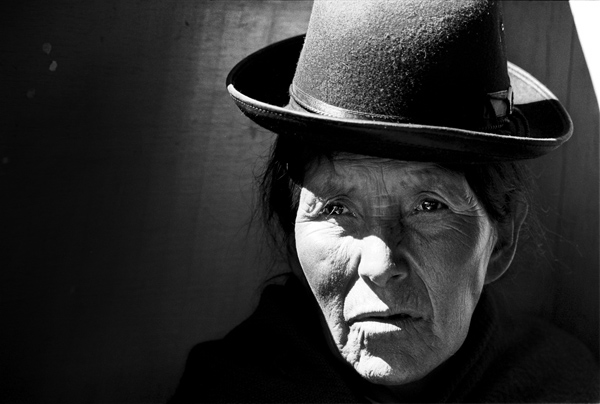

The term “vanishing culture” is frequently used to describe a process that has been occurring for centuries. Cultures are fluid and in a constant state of change. What we now think of as “signs” of the indigenous, such as round, black hats on Aymara women, may not have been recognizable to the same tribes hundreds of years earlier. Many of these “signs” are imports from non-indigenous cultures. I show this cycle of cultural change by photographing isolated indigenous populations, peoples living in mixed cultures, and areas where Indians have become extinct.

For nine years, I photographed in areas of Latin America with large indigenous populations. I worked with Maya in Southern Mexico and Guatemala, Aymara in Bolivia, Quechua in Peru and Ecuador, Tarahumara in Northern Mexico, Guaraní in Argentina and Paraguay, Yagua in the Amazon, and Nivacle in Paraguay, to name just a few. I photographed the vanishing and merging cultures in twelve countries, from the southernmost city in the world in Tierra del Fuego, where the native populations were annihilated, to the Tarahumara cave dwellers of the Copper Canyon on the Mexico-Texas border.

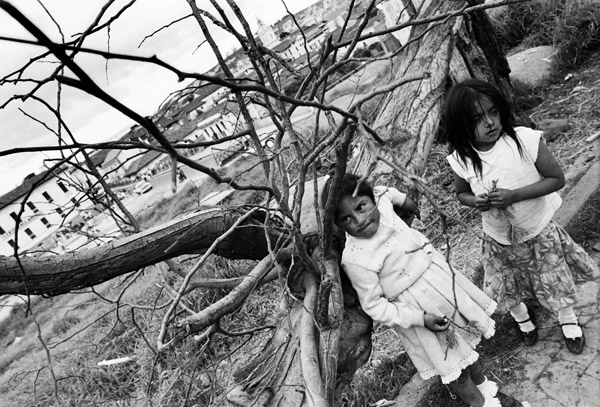

These fifteen images are a small sampling of a larger project. They are documents of street life that show how people live, work, and lead their daily lives. The photographs show the merging of the Indian and Latin cultures and the changing ways of life. They question what it means to be indigenous.

They say there is a city of dolphins at the bottom of the Amazon waters. A lost city. Time passes slowly down there. One day below equals one year above. The pink dolphins of the Amazon don’t have enough mates. So the male dolphins swim to the surface and steal Amazonian women, and the female dolphins steal handsome men. If you stay underwater and live the dolphin life, time appears normal. But when you return to the surface, your village is gone, and a modern city has taken its place. Your family and friends are dead. Eventually, you age as you should and turn to dust as your long-dead ancestors.

They call the pink dolphins “witches”—bad, pink witches.

He gives a hiking tourist directions on how to reach the bottom of the deepest canyon in the world. Then the Tarahumara sits on his bench on the rim of the Copper Canyon and carves a stick and a ball. His shadow points the way.

Like musical notes, the pigs hang in an uneven line. Women inspect and decide on their favorite slabs. A cat hides around the corner, hoping for handouts. A man humming and whittling sticks waits for his wife to shop.

Easter morning on Lake Titicaca. A baby monkey grasps a necklace charm with a fuzzy image of the Virgin of Copacabana. Aymara Indian women in shiny skirts tease children by chasing them down the street with a stuffed frog that has colored stars on its back. Street vendors sell strings of fresh roses for twenty cents and images of the Virgin in barnacle-covered oyster shells. Believers pray for new homes while drunk, chanting priests perch faded plastic houses on their heads.

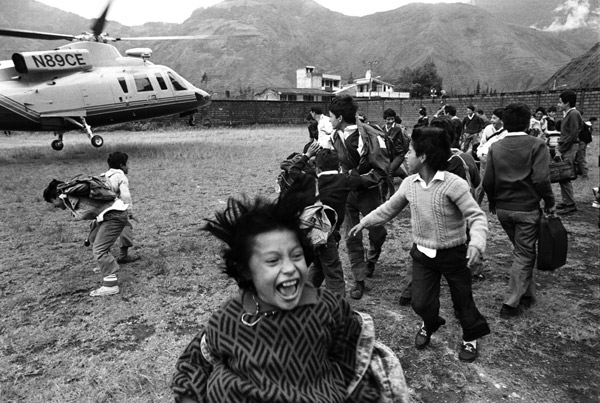

Blades slice thin air and squeeze between mountain peaks. Crowds race down cobbled streets toward the soccer field. Boys spin in circles with arms outstretched and little girls squeal and scream. Parents giggle and sprint ahead of the crowd. The helicopter descends, and the twirling boys push each other closer to the blades. An elegant leg steps out, and a rich visitor comes to town.

Confetti drips like melting snow from hats onto sour shoulders. The day is festive, but they are not. The bride walks out. A guest lifts a hat to sprinkle the woman with more flakes. But nothing touches their faces.

They stare at the sea. Their ancestors came on that sea—slaves—shipwrecked to short freedom and then shuttled to an island off Honduras. These are the Garifuna. They dance with the wind.

View from a damp hotel window. I lift off my blanket as the clouds unveil the town.

Gerónimo carries a pickaxe on his neck and smiles with a chipped tooth. He steps into the mist while his feet break muddy reflections. In the distance, army drums echo tunes of revolution.

Two priests in white satin robes plant their feet in front of towering church doors. Patrons gaze from the plaza below while the priests stand silently for photos. Children with gladiolas and men carrying wooden St. Christophers on their shoulders bow their heads as they pass the priests. Shoe-shining Indian boys giggle behind the robes. Three lambs carved out of papayas with furry fruit hair greet people as they enter the church.

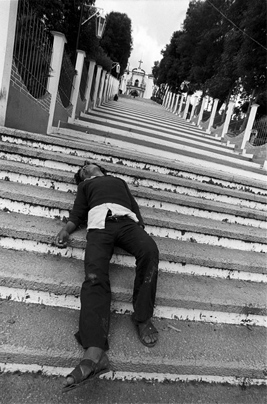

Dozens of steps on the way to heaven. A drunk walks a few and dreams the rest.

They light tires and cardboard boxes. They run through the flames protected by the spirit of Saint Martín. Children giggle. Parents smile. Fumes rise to heaven.

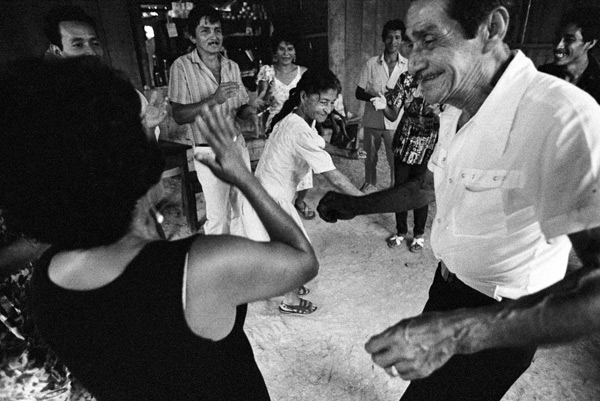

She’s sixty-four and dances like Chubby Checker. Green ruffles at the bottom of her dress twirl when she squats, wiggles her hips, and raises her arms. It’s Mother’s Day on the Amazon, and she shouts her motherhood as she celebrates with her family. She guzzles the beer-egg milkshake and opens her eyes wide. “You drink half, and I drink half,” she insists as she passes the bottle covered with lipstick smudges the color of cotton candy. “For Mother’s Day. To the mothers!”

Winding streets and twisted trees in the Old City. The Virgin of Quito looks over the city from the highest peak, guarding the children who stare through those branches.

Tierra del Fuego. The Land of Fire, where before they were extinct, the Fuegians warmed themselves by flames. Tierra del Fuego. The End of the World.

The nation is divided. After the last election, one party dominates the government. It has sustained its hold on the presidency and bolstered its majorities in Congress. Its newly elected president will likely appoint several justices to a closely divided Supreme Court. The situation looks bleak for the opposition, which during the campaign failed miserably to articulate what, exactly, they stood for. Their politics, scoffs one columnist, are “hardly more than an angry cry of protest against things as they are.”

But the opposition has been mobilized. The last campaign was an ugly, embittering experience, but it brought countless new soldiers into the party and into the cause. A journalist writes:

It was something more than just finding ideological soul mates. It was learning how to act: how emails got written, how doors got knocked on, how co-workers could be won over on the coffee break, how to print a bumper sticker and how to pry one off with a razor blade; how to put together a network whose force exceeded the sum of its parts by orders of magnitude; how to talk to a reporter, how to picket, and how, if need be, to infiltrate — how to make the anger boiling inside of you ennobling, productive, powerful, instead of embittering. How to feel bigger than yourself. It was something beyond the week, the year, the campaign, even the decade; it was a cause.

The election I have in mind is not the election of November 2, 2004, but the one of November 3, 1964 — when Democratic incumbent Lyndon Baines Johnson crushed his Republican challenger, Barry Goldwater. (Just to keep you on your toes, I substituted “emails” for “letters” in the quote above.) This was the pivotal election that ushered in the rise of the American conservative movement, an unlikely coalition of cultural warriors and economic elites who have dominated the nation’s politics for the last two decades.

Rick Perlstein (the journalist quoted above) chronicles the 1964 election in his book Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus. Goldwater was the candidate of the Republican wing of the Republican Party. He went down in blazing defeat, but his campaign galvanized conservatives across the country. “Scratch a conservative today: a think-tank bookworm at Washington’s Heritage Foundation … a door-knocking church lady pressing pamphlets into her neighbors palms about partial-birth abortion … an organizer of a training center for aspiring conservative activists or journalists … and the story comes out,” Perlstein writes. “How it all began for them: in the Goldwater campaign.”

Past is not always prologue, but what happened then does offer Americans some idea of the possibilities for changing what is happening now. The Democratic Party lost the last election, and the defeat was devastating. Yet amid all the confident declarations of its imminent political demise — that the party is a “national party no more,” that it lacks a clear message, that it must change its values to match those of Middle America — we may lose sight of the fact that Democrats are building, as the Republicans did four decades ago, a grassroots network. This fact alone should give Democrats hope moving into the second term of a second Bush administration, even though the fight remains a long and uphill one.

The Republican revolution

Americans have forgotten how sharply political attitudes have shifted in the last half-century. In 1964, conservatives were fighting to be taken seriously in their own party. The Republicans who did win national office were largely moderates. The Republican Party’s only winning presidential candidate in three decades, Dwight Eisenhower, presided over a substantial growth in federal government programs: the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, the federal interstate highway system, the expansion of low-income housing. (He also declared his staunch support for the biggest “big government” program of all, Social Security.)

The blow dealt to conservatives by Johnson’s landslide victory left them chastened. The numbers (61 percent for Johnson, 39 percent for Goldwater) did not lie: The conservative agenda had been roundly — awesomely — rejected. A consensus had emerged, the pundits of the time said, in favor of government solutions to social and economic problems.

“By every test we have,” said presidential scholar James MacGregor Burns, “this is as surely a liberal epoch as the late 19th Century was a conservative one.”

Two years later, the Republicans seized ground in the House and Senate, and ten conservative governors were voted in. Two decades later, Ronald Reagan smothered his Democratic challenger Walter Mondale in a blanket of red, leaving only Washington D.C. and Mondale’s home state of Minnesota untouched. Three decades later, the Republicans swept into power in both houses of Congress. Four decades later, Republicans dominate all three branches of government.

The ingredients of the Republican revolution were, to some extent, the usual mix: wealthy financiers, charismatic leaders, a brain trust of conservative intellectuals. But the heart of the movement was its foot soldiers. Many had been baptized in the ruin of the Goldwater campaign; now they were raising money among their neighbors, running for local offices, and immersing themselves — with zeal and excitement — in the American political process.

In a word, they organized. “These low-budget, no-frills, volunteer driven, high-tech groups packed grassroots punch with blazing efficiency and little overhead,” writes Ralph Reed, one of the architects of the grassroots network of evangelical Christians that came to prominence in the 1980s. “Housewives at kitchen tables, home schoolers perched before personal computers, businessmen burning fax lines, and precinct canvassers identifying voters formed a grassroots network without parallel. At first few took notice of their existence, and the absence of many headline hounds in their ranks delayed their appearance onto the national political scene. Most felt uncomfortable with the limelight. They were simply citizens, parents, and taxpayers organizing others of like mind.”

Ralph Reed’s Christian Coalition started off by building a grassroots presence in all 50 states. Their candidates took control of local school boards. They fought ferociously over state legislation and local ordinances. “Rather than tune the rhythm of the group to election cycles,” Reed writes in his book Politically Incorrect, “we focused on the long-term picture, assembling a permanent organization that would represent people of faith in the same way that the Chamber of Commerce represents business or the AFL-CIO represents union workers.”

Slowly, power at the grassroots translated into power in Washington. In the 1992 election, the voter turnout of self-identified, born-again evangelicals was the largest ever — an estimated 24 million, or one out of every four voters.

The cultural conservatives lost that presidential election, but they made inroads at the state and local level. What’s more, the Clinton presidency radicalized evangelicals, bringing countless new activists to the movement. It was, in Reed’s words, “a wake-up call for many churchgoing voters who had retreated from the political arena after the Reagan years.”

The liberal president won a second term, but the cultural conservatives regrouped in larger numbers. They were the troops who voted George W. Bush into office in 2000. They were the ones who stormed the polls in 2004, again in record numbers, to keep Bush in the White House and keep alive the dream — afloat on the backs of 11 state ballot measures — that gay marriage would be outlawed across the land.

They succeeded on both counts.

A battle lost, a war begun

On the other side of the aisle, the question is, “What went wrong?” Much was made of Howard Dean’s grassroots-based, Internet-powered campaign that brought legions of young people into politics. Then the candidate stumbled in the primaries, and the “Dean machine” was written off as hype. Much was made, too, of the bloggers and small donors who gave a much-needed boost to the campaign of Senator John Kerry, as well as the unprecedented numbers of new voters who registered in the months leading up to the election. But when the votes did not materialize for Kerry on November 2, pundits pooh-poohed the Democratic Party’s faith in the not-seen. They shouldn’t have had so much confidence in young voters known to be fickle and unreliable. They shouldn’t have expected to win the ground war in Ohio and Florida. They should have known all along that ordinary Americans care about personality more than policy, values more than health care, terrorism more than the economy.

“Kerry was counting on millions of first-time Democratic voters to carry him through, and millions apparently did turn out, but probably not enough to make the difference,” went The New York Times’ postmortem. “… Only about half the voters yesterday had a favorable view of Kerry, about the same as for Bush, and he dueled Bush only to a draw on who would best handle the economy … Voters who cited honesty as the most important quality in a candidate broke 2 to 1 in Mr. Bush’s favor.” (Christian soldiers, on the other hand, came out in droves for their leader: This time, a third of voters identified themselves as evangelicals, and they voted overwhelmingly for Bush.)

It was not that the Democrats did not have a “ground game” — it was that the Republicans, having been at this for four decades, had a much better one.

Now, staring at the wreckage of the Kerry campaign, progressive activists have many reasons to second-guess their efforts over the last few years. They may be discouraged by their failure to build a winning grassroots organization. They may be tempted to soften their populist rhetoric of equality and opportunity, to retreat from their stands on controversial issues like gay rights — all in an effort to appeal to middle-of-the-road voters who apparently spurned them this last time around.

To some extent this repositioning will be necessary. Without a message that appeals to voters across the nation’s vast cultural and socioeconomic spectrum, there is little hope for victory at the polls.

But the lesson of the Goldwater campaign of 1964 is that political attitudes are not frozen in time. A well-organized network of citizen-activists can change minds and win votes, one person at a time. The triumph of one party and one ideology can, in a matter of decades, be utterly reversed. The good news for Democrats is that time is on their side. Like Clinton radicalized evangelicals, Bush has radicalized progressives. From MoveOn.org to Air America Radio, grassroots organizations and media outlets have sprung up in the shadows of Republican political dominance. They will continue to flourish now that a president as polarizing as George W. Bush will be in office for another four years.

There are leaders in the Democratic Party who recognize the importance of this street-level strategy. “Instead of doing this from the top-down, you need to make people feel they have power over their lives again,” said Howard Dean, speaking at a forum during the Democratic National Convention last July. “The way you win presidential elections is to make sure the local elections are taken care of first. We can’t win a national election unless we’re willing to take our case to Alabama and Texas.”

Democrats can also take heart in the long-term demographic trends in this country, which favor their party. John B. Judis and Ruy Teixeira make such a case in The Emerging Democratic Majority — a book whose title alludes to Kevin Phillips’ 1969 classic, The Emerging Republican Majority, which presciently heralded the rise of the conservative movement. Like tectonic plates slowly grinding beneath the surface, the political realignment that Judis and Teixera describe may be gradual and barely noticeable, but they insist it is real. A browner population, a postindustrial economy, and a burgeoning class of educated professionals will help the Democrats win votes and reclaim lost ground over the next decade. With a white population that tends to vote Republican remaining static, the growing Asian, Hispanic, and African American communities can become the foundation for this uprising — if the Democratic Party establishes the grassroots network necessary to reach out to them and mobilize their numbers. (Younger voters, too, must be tapped: They voted in large numbers for Kerry and tend to be less conservative than their elders on social issues like gay marriage.)

Of course, there is no inevitability in history. The blogger revolution and “Dean machine” of 2004 might turn out to be just another political fad. A multicultural America could easily be co-opted by Republicans with enough savvy to shift with the tide. Younger voters, slightly roused by this last election, may very well sink back into apathy. Yet, the possibility exists for transformation — for a profound realignment of American politics. Like 1964, 2004 could be a turning point. Those who despair need only look at what Goldwater’s faithful accomplished in the years after their humiliating defeat. “You lost in 1964,” Rick Perlstein writes of the veterans of that earlier campaign. “But something remained after 1964: a movement. An army. Any army that could lose a battle, suck it up, regroup, then live to fight a thousand battles more.”

Victor Tan Chen Victor Tan Chen is In The Fray's editor in chief and the author of Cut Loose: Jobless and Hopeless in an Unfair Economy. Site: victortanchen.com | Facebook | Twitter: @victortanchen

I went to bed Tuesday night praying for a miracle.

I’ve spent the last year following and occasionally writing about the presidential campaigns. And all year — especially since covering the Democratic National Convention in July when I pretty much resigned myself to four more years of Dubya — I tried not to get my hopes up. I mean, if you can’t manage a simple balloon drop, how are you going to outfox Karl Rove?

When you grow up in Boston, you come to realize that no matter how much you pray that your guy will prevail, he’ll usually find a way to blow it. Until two weeks ago, our Red Sox hadn’t won a World Series in 86 years. In fact, just about the only reliable thing about the Red Sox was that they would find new and ever more excruciating ways to lose when victory seemed so close, so possible.

But that was our October surprise. This week, still elated — and partially blinded — by an improbable Red Sox win, I allowed myself to contemplate the possibility of a John Kerry presidency. By 8 p.m. on Election Day, I was actually confident of Bush’s ouster. On the basis of preliminary exit polls, the nit-wits on right-wing radio were almost ready to concede. On Fox News, droopy dog Brit Hume seemed so defeated that his face looked as if it was ready to slide completely of his head. What could possibly go wrong?

Of course, we know what went wrong. Somehow, Kerry found a new and more excruciating way to lose. The exit polls were wrong. But this time, the election wasn’t stolen — we lost it. Instead of waking up to a miracle, I woke up to endless clouds and a cold hard rain.

But if I’ve learned anything from being a Red Sox fan, it’s this: There’s always next year. Or in this case, there’s always 2008.

So it’s time to stop crying in our lattes. Every cloud, even the towering gray cumulonimbus that is the Bush presidency, must have a silver lining.

Right?

In case you need to be talked down off the ledge — or the next flight to Vancouver — here are a few things that might cheer you up. Maybe.

For those who are truly desperate, those for whom no baseball analogy is a comfort, those who believe that 2008 is way, way, way too far away, there is one last consolation: While everyone was trying to figure out which of his three Purple Hearts John Kerry actually deserved, George W. Bush let the assault weapons ban lapse. So when they start shutting down the libraries and museums, you’ll be well armed for secession.

“If we want to have a hopeful and decent society, we ought to aim for the ideal, and the ideal is that marriage ought to be, and should be, a union of a man and a woman.”

— Karl Rove, in a statement aired today on Fox News Sunday. Mr. Rove, as Senior Advisor to President Bush, is largely responsible for President Bush’s rise to the White House and for engineering many of the president’s policies.

As a testament to Karl Rove’s disconcerting grip on both President Bush’s ear and on American policy, John DiIulio, former director of the White House Office of Community and Faith-Based Initiatives, stated: “Karl is enormously powerful, maybe the single most person in the modern, post-Hoover era ever to occupy a political-adviser post near the Oval Office.”