Does anyone need a quick refresher on the filibuster and how it has been used by various political parties in the United States over the last two centuries? A website designed by the People For the American Way takes a look at the history of the filibuster in action, as well as current myths surrounding it, and how its disappearance might affect the American ecosystem.

The first Supreme Court nomination approaches as the Bush administration begins another four-year term. Use of the filibuster by Democrats during Bush’s last term successfully impeded 10 of Bush’s 52 appeals court nominees. As a result, Republicans contend that Democrats are “trampling on the Constitution” with their “abuse” of the filibuster, according to an article last month in The Washington Post by reporters Helen Dewar and Mike Allen. Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist has suggested he “may resort to an unusual parliamentary maneuver, dubbed the ‘nuclear option,’ to thwart such filibusters.”

An editorial available on the PFAW website argues the merits of the key role the filibuster process plays in the legislative process. It explains,

“The modern-day filibuster, a Senate procedure that requires sixty senators to agree to a vote on significant issues, is an essential check on the abuse of majority power and can be an effective strategy for achieving bipartisan cooperation.”

Popular arguments against the use of the filibuster claim that in the past, senators have exploited its use. A United States Senate website notes these arguments, as well as the ends toward which filibusters have been implemented.

“Many Americans are familiar with the hours-long filibuster of Senator Jefferson Smith in Frank Capra’s film Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, but there have been some famous filibusters in the real-life Senate as well. During the 1930s, Senator Huey P. Long effectively used the filibuster against bills that he thought favored the rich over the poor.”

What if the use of nuclear weapons were protested based upon the potential that the wrong people might exploit their use? What if such protests were effective?

Activists interested in signing a petition to save the filibuster can find it on the PFAW website.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

A question of honor

The sexual mores of Egyptian culture confine sex to marriage, but marriage in Egypt is an expensive enterprise. For the upper middle class, it requires rings with diamonds — and many of them — a furnished apartment and lavish engagement and wedding parties to entertain the entire extended family. Families with less money haggle over the prices of refrigerators and washing machines. The expense and stress of what can be viewed only as a thinly veiled business deal between two families intent on solidifying their relationships means that marriage is often postponed until both parties are in their late 20s.

While furnished apartments and bathrooms with marble, not tile, may be the topics of discussion during these family negotiations, the consummation of an Egyptian marriage ultimately rests on the woman’s virginity. Since there’s no male virginity test, women bear the responsibility for upholding their culture’s sexual morals, and they pay a high price for it. In rural and poor communities, honor killings, like this recent one in Kuwait, are carried out by relatives in an attempt to preserve their families’ honor, and rid the family of both the shame and economic burden of having an unmarriageable female in the family). Among the middle class and wealthy, losing your virginity before the wedding night entails a visit to a plastic surgeon to have your hymen reattached. Unlike in the United States, single mothers aren’t a demographic, or the target of social services programs — they simply don’t exist.

Or, to be more accurate, they don’t exist publicly; or at least, they didn’t, until now. Hind el-Hinnaway, a 27-year-old Egyptian costume designer and single mother, has captured national attention and sparked what many hope will blow open discussion about women and sexuality in Egypt. El-Hinnawy has filed a paternity suit against the famous television actor Ahmed el-Fishaway, demanding that he take responsibility for their child. The two met on the set of his television show and allegedly entered into a civil marriage — a contractual relationship that does not require a wedding, but permits a couple to cohabitate. She became pregnant, and chose to go ahead and have the child rather than have an abortion. When el-Fishaway chose to ignore her, she took him to court and is now suing him in a landmark paternity case — the first in Egypt to use DNA testing.

El-Hinnawy hopes the case will force Egyptians to examine the hypocrisy embedded in their society, which increasingly embraces a model of gender relations embedded in what many consider a dangerously conservative interpretation of Islam.

“I did the right thing: I didn’t hide, and eventually he will have to give the baby his name,” she said. “People prefer that a woman live a psychologically troubled life; that doesn’t matter as long as it doesn’t become a scandal.”

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

MAILBAG: God’s politics, but whose god?

Jim Wallis’s new book and his engagement in political life is welcome and beneficial. Finally left-leaning theists are getting a high-profile voice to expose the hypocrisy of the Republicans’ policies.

Why, though, must he use the term “Christian evangelical?” Does he really have to alienate a large percentage of the voting public that way? There is a long and abusive history of repression by evangelicals. Even to say “Christian values” is a slap in the face for Jews, Muslims, Hindus, etc.

Why not just say God’s values? We all worship the same one God in different forms. In each religion His/Her professed values are virtually the same, except of course to the fundamentalists and atheists.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

A writer on reading

A whole slew of less-than-thrilling books have been written about writing. Many others have been written that belong to the category of writers on reading. Nick Hornby recently published one of these.

Of course, there has been an article written about the book that Mr. Hornby wrote about reading other books, or not reading them, as he readily admits and then writes about. (Read on for details about the book, titled The Polysyllabic Spree: A Hilarious and True Account of One Man’s Struggle With the Monthly Tide of the Books He’s Bought and the Books He’s Been Meaning to Read.)

Shockingly, the article by Carol Iaciofano in The Boston Globe actually made me want to buy the book. She writes, “But buying books is half the fun. For anyone who’s ever browsed around a bookstore, reading Hornby’s accounts of how one book led him to another, or how he discovered a new author nearly by accident, is like reconnecting with an erudite friend.”

Who knows, maybe I’ll buy the book — or even read it.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

Quote of note

“Neither religious nor secular fundamentalism can save us … but a new spiritual revival that ignites deep social conscience could transform our society.”

— Jim Wallis, Christian commentator, editor, and author, most recently of God’s Politics: Why the Right Gets It Wrong and the Left Doesn’t Get It.

Jim Wallis characterizes himself as a “progressive evangelical,” — not to be confused with a Democrat, since his views can veer to the right of center — and he condemns both the Republican and Democratic approach to faith and political life. In his recent book, Wallis claims that while the conservatives have successfully harnessed the power of religious language for political gain, the Democrats, in propounding the secularist cause, have both lost the most recent elections and lost sight of what Wallis believes should be the American goal — to move beyond partisan politics while embracing Christian values.

The left “doesn’t get it” because it refuses to reintroduce Christian values into the Democratic platform, which allows the Republicans to enjoy a stranglehold on the religious voice in American politics. The right, on the other hand, is “wrong” because it manipulates religious language for a political agenda that is inconsistent with the Christian tradition. The way to change the status quo, Wallis claims, is not for the Democrats to move away from Christian values; the solution is for Democrats and, indeed, all Americans, to embrace and reintroduce Christian values into the political spectrum.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

Quote of note

“Things are now clearer than ever: We have the right to feel a chill down the spine. To describe Bush as a madman with a mission at the head of a state bristling with weapons does not really get us any further … and, although insulting, it is no longer even particularly original. And yet this U.S. administration sends a chill down the spine of anyone unwilling to become accustomed to listening to this madness.”

— the German publication Die Tageszeitung, responding to President Bush’s second-term inauguration.

While George W. Bush escaped the controversy and legal wrangling that sullied the presidential election four years ago, his domestic approval rating now only scrapes in at around 50 percent, which is staggeringly low; the previous second-term president to have had such a low approval rating was Dwight Eisenhower in 1957.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

The inauguration photos the mainstream media failed to publish

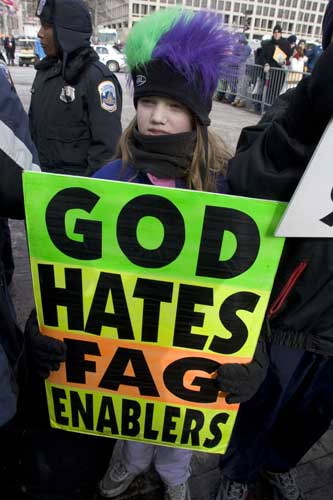

When InTheFray Visual Consultant Dustin Ross attended President Bush’s inauguration on Thursday, he saw the predictable protesters — and some unbelievably uncompassionate conservatism. See for yourself:

Members of the Westboro Baptist Church of Topeka, Kansas, protest George Bush’s inauguration. I overheard one of the members saying “God hates

fags, God hates fag enablers, therefore God hates George Bush.”

Lines stretched for blocks as people tried to enter the parade area for President Bush’s inauguration. Security checkpoints only let a few people in at a time, and people with bags were not allowed into the area.

Star, a patriotic clown, by the parade route during the inauguration for President George Bush.

A protester dresses as a prisoner from Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

A dream of dissent, undeferred

The last line in a letter written by the activist group Ladies of Liberty reads, “Remember: Dissent is Patriotic.” Their message is timely. On Thursday, President Bush will be re-inaugurated. The rage which inspired activism after Bush claimed the presidency in 2000 appears to have subsided into a lethargic response of depression and denial, as The Stranger’s Amy Jenniges reports:

“For lefties who became political activists for the first time in their lives last year, the realization that their hard work didn’t turn Bush out of office has translated into feelings of grief, frustration, depression, apathy, and denial — but not anger. Anger can inspire people to protest. Depression and denial lead people to hibernate, drink, and check out of politics.”

With many freedoms at stake, the Ladies of Liberty are one of several protest groups who will march in counter-inaugural rallies this Thursday, January 20th. The Ladies have organized a peaceful protest in the form of a funeral procession and will be accompanied by a New Orleans-style jazz band in mourning for “the multiple blows to the American people dealt by the Bush Administration (and the prospect of four more years of the same), as well as [in celebration for] the possibilities of rebirth and regeneration.” The blows the Ladies cite include those to the areas of women’s rights, gay rights, reproductive rights, social security, the democratic process, environmental conditions, free speech, principles of inclusion, economic equality and freedom from arbitrary imprisonment.

Some American citizens view Bush’s majority win in 2004 as a justification for silence, although they oppose his administration. Still others envision his victory as a last-ditch effort on the part of conservative America to protest the increasing speed of life in the 21st century by grasping at any straw which might slow the process down. Groups like the Ladies of Liberty voice the belief that multiple perspectives are not only rooted in American culture, they must be nurtured and provided with plenty of sunlight.

“Now the trumpet summons us again,” said John F. Kennedy in his 1961 Inauguration Speech, “not as a call to bear arms, not as a call to battle, but a call to bear the burden of a long twilight struggle, year in and year out, rejoicing in hope, patient in tribulation.”

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

Quote of note

“Yes, if you want to say that I was a drum major. Say that I was a drum major for justice. Say that I was a drum major for peace. Say that I was a drum major for righteousness. And all of the other shallow things will not matter. I won’t have any money to leave behind. I won’t have the fine and luxurious things in life to leave behind. But I just want to leave a committed life behind. And that’s all I want to say. If I can help somebody as I pass along, if I can cheer somebody with a word or song, if I can show somebody he is traveling wrong, then my living will not be in vain.”

— Martin Luther King, Jr., in his 1968 sermon titled “The Drum Major Instinct.”

Coretta Scott King, the wife of the late Reverend King, has written an essay for The King Center in which she explains the meaning of today’s holiday, which celebrates the life and legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

Occupation’s death grip

The war in Chechnya has drained the lifeblood from a once powerful Russian army, and it doesn’t look like it will end anytime soon.

A squat military van parked in the middle of Pushkinskya Street last summer. Surrounded by military schools and bases, soldiers crossed this pedestrian mall every day. In Rostov-on-Don, the military enjoyed particular freedoms with parking and traffic laws.

Last summer, hundreds of soldiers strolled down the leafy sidewalk on Pushkinskaya Street daily, enjoying the pedestrian mall that crisscrosses the heart of Rostov-on-Don in southern Russia. In July, they wandered past neat-trimmed grass, flower gardens, outdoor cafes with plastic patio furniture, and past the concrete dividers that border them.

This street was named after a poet, but warriors dominate the city founded along the Don River, a century-old shipping route and crucial frontier, less than 500 miles away from Chechen border. Two military bases, two military academies, a regional recruiting station, and the headquarters for the Great Don Cossack Army all lay within walking distance. The city’s 1.2 million inhabitants have spent their entire lives surrounded by military outposts that are a microcosm of the troubled Russian army. Civilians mingle with a sea of uniforms: boy-soldiers in camouflage, officers in crisp dress, and off-duty recruits in khaki civilian clothes and sunglasses to hide their eyes.

At the end of last summer, wreckage from an exploded airplane fell just outside this city, changing everything for these soldiers. The guerilla war in Chechnya had jumped the border to Russia with renewed intensity. In just a few weeks, Chechen suicide bombers had destroyed two airplanes, bombed a Moscow subway stop, and murdered hundreds of children in a Beslan schoolhouse. In response, Russian President Vladimir Putin summoned military forces to tighten borders, pacify Chechnya, and protect Russia.

The increased attacks, however, only highlighted problems with Russia’s military that have been brewing for years. Russia’s terrorism policy rests in the hands of thousands of young men from the Rostov region, pulled into the army every year under a confusing set of draft laws that many find ways to evade. According to many active soldiers and their advocates, the army is a poorly financed and demoralized force. Although the government responded last January with initiatives to build a contracted army, it is unclear how effective the reforms will be or how they will help extricate Russia from a war that it cannot win.

As troubled Iraqi elections loom — and the logistics of a deadly American commitment to Iraq become more problematic under a protracted occupation — the state of Russia’s military after a decade-long conflict offers a troubled example for Americans.

Pushkinskya Street is the community center in Rostov-on-Don, Russia. During the day, cars parked haphazardly outside the shops and offices lining the long stretch of flowery sidewalks. In the evening, residents strolled past countless outdoor cafes and chatted with their neighbors.

Filling the ranks through “coffin money”

A few blocks away from Pushkinskaya, kitty-corner to a grade school, lies a sprawling red brick building guarded by recently graduated teenagers with machine guns. The Southern Region Recruiting Station was the first station to institute a new set of military reforms earlier last year, trying to fill the army ranks with a better kind of soldier.

This station began accepting applications last January, part of the military’s plans to convert half the army into contractors by 2007. For years, the army found soldiers under a mandatory conscription law, drafting soldiers for two years from a nationwide pool of 1.2 million young men between 18 and 27 years old — drawing boys into complicated conflicts for which they were ill prepared. While small numbers of contractors have also served in the Russian army and navy for many years, the army now plans to dramatically increase this pool of voluntary fighters.

As Vice-Military Commissar of the Rostov Region, Colonel Valery Tolmachev supervised the contractor recruiting drive last year. He explained that the current, drafted army suffers from an “intellectual poverty.” While the Russian draft calls hundreds of thousands of young men, wealth and education often determine the final cut. Recruits can avoid the draft through special work and university deferments, and many wealthier draftees pay to keep their names off the register. The army is struggling, even in this military-saturated region.

Too many of the best and brightest have managed to escape service, leaving the poor and undereducated to lead the ranks. Accusations of hazing and power abuse sometimes filter down through the ranks, reflecting the difficulties of an army staffed with unwilling or unhappy troops.

With a cautious smile Tolmachev expressed hope in these new contracted soldiers, expecting that this additional force of willing and experienced fighters will replace the weaker, drafted soldiers. “People were eager to serve under contract; even women came to sign up.”

In contrast to draftees, contract soldiers are paid at higher rates with additional pay for wartime experience or special skills. For instance, contract soldiers in the 42nd Motor Rifle Division earn 15,000 ($510) rubles a month for service in a Chechnya hotspot — almost 10,000 ($340) rubles more than the average, drafted recruit.

Colonel Tolmachev estimated that contractors now compose 25 to 30 percent of the whole army, only a small rise from last year. However, increased contractors have also lowered the mandatory service requirement to one year, loosening the two-year draft policy that forced thousands of young men into the army. So far, the change has mostly affected “commandants,” placing contractors at military outposts in highly dangerous conflict areas.

While American contractors perform similar services in Iraq, repairing the battered infrastructure, leading supply convoys through the desert, and running dangerous military missions, the U.S. government has not yet raised the pay-stakes as dramatically as the Russian army. However, as that conflict’s resemblance to the guerilla nightmare of Chechnya increases, the pressure for improved compensation to avoid a draft builds.

Tolmachev called the high-risk incentives paid to contractors in dangerous Chechen outposts “coffin money.”

A tug floats along the Don River last summer. For centuries, this long river watered agriculture and guided freight ships through the vast southern interior of Russia.

Curator of misery

Tolmachev’s term appropriately gestures towards the military quagmire that the Chechnya conflict has become. In the mid-1990’s, the Russian military crashed into this unconventional war. It sent thousands of drafted soldiers into the fiercely independent Chechen region — without preparing them for the duration or tactics of the conflict.

The latest insurgency is an outgrowth of longstanding tensions between the Russian government and Chechnya. Though an autonomous Chechen-Ingush republic was established under Soviet rule, World War II brought a vicious crackdown under Stalin when thousands of Chechens were deported for allegedly collaborating with German forces. The Chechen republic was reestablished in 1958, but the earlier exile of its citizens scarred its relationship with Russia.

Post-Soviet chaos bred violent separatist movements in Chechnya, and these rebels mounted waves of terrorist attacks on Russian soil — demanding an autonomous state. The Russian government resisted, and sent troops to break up terror cells in Grozny in 1995. Soon the insurgency situation degenerated into crisis.

Just like the U.S. military in Iraq last year, Russian forces discovered that full-scale occupation could not stop suicide bombers and urban guerillas. The military was not able to pacify the besieged country, and the insurgents evaded military control. These tactics led to a protracted conflict, and a second war commenced in 1999. Since then, thousands of troops have died, and a string of terrorist attacks have squandered hopes for a clean exit strategy.

Svetlana Arsenyevna Lozhkina, chair of the Rostov Region Committee of Soldiers’ Mothers, has seen the consequences of this bloodshed firsthand, and she has a large supply of stories about the soldiers who have suffered or died in this conflict.

Nestled on the bottom floor of the colonel’s recruiting station, her office is a cozy space plastered with newspaper clippings about boys hurt, lost, or killed over the last 10 years of military action in Chechnya. Her committee formed in 1989, created by mothers who had lost children in war. Lozhkina joined the group after her son returned safely from his mandatory service, turning her motherly concern into a public service project. Over the past 15 years, Lozhkina has filled dozens of ledger-books with complaints from drafted soldiers, documenting the struggles of young men trapped in dangerous posts.

Despite the tired wrinkles around her eyes, Lozhkina speaks intensely. “I don’t keep track of numbers, but at least seven people come in here each week during the summer. Many more people come during the Army’s fall recruitment drive to complain about their service.”

Lozhkina reads a letter from a soldier stationed in North Ossetia — the site of the then-unexpected Beslan massacre. Private Vilady alleges that two soldiers were infected by hepatitis during routine flu shots and that officers beat soldiers hard enough to rupture organs. The soldier concludes, “We don’t care what we have to do. We’ll do anything to get out of this hell.”

Every day, she carefully prints the name, address and complaints of new soldiers in a five-inch thick notebook. She’s a curator of misery, and 2004’s ledger was already half full in July.

Every day, the American military records similarly grim statistics. There’s no draft randomly pulling out college-aged soldiers, but already American soldiers have been forced to extend their tours while more reservists have been pulled into the conflict. The streets of Grozny are as untamed as the shadowy walls of Falluja in Iraq. If the insurgency and American occupation should drag on for another five or 10 years, some mother will have to fill ledger books with the names of American soldiers.

A view of Rostov, taken from a ship floating along the Don River last summer. The Don Cossack ethnic group settled along these green banks, raising horses and training generations of proud warriors.

A special breed of soldier

Lozhkina’s ledger captures the fear and inexperience of young draftees, the kind of problems the army hopes to avoid with professional soldiers. Studying the contract soldier program, it is apparent that many Rostov region contractors are Cossacks — a brash group that eagerly signed up out of ethnic pride. These soldiers are reputed to enter war zones fearlessly, but they’ve also faced a new set of problems within the contract soldier system.

Inside the Rostov-on-Don headquarters of the Great Don Cossack Army, rows of training photographs decorate the skinny, dim hallways. The army is named after the Don River that flows past Rostov, the fertile water that lured this proud ethnic group to settle here in the 17th century, and defend the southern frontier. The pictures show children training in Cossack military schools: little boys in greasepaint and camouflage, teenagers scrambling up walls; recruits riding horses, kissing flags, or practicing karate moves.

While the death toll in Chechnya sends many rich Russian teenagers running from the draft, this is still a city of warriors. Out of all the military-men debating the future of the Russian army, these fighters tell the most optimistic stories.

The Cossack tradition of raising soldiers from childhood is long standing. In the 17th century, the group pledged allegiance to the Czar, but maintained sovereignty and traditional values within their communities. In the 19th century, they became an independent arm of the Russian military, establishing these Cossack outposts and schools in the region.

A giant blue, yellow, and red Don Cossack flag dangles in Vladimir Voronin’s office, decorated with the Cossack army’s seal — a white stag leaping with an arrow buried in its belly. “Cossacks are more eager to serve than other people,” said Voronin, the Commander of the Directorate of Ideology and Propaganda of the Great Don Cossack Army.

His plastic glasses perched on the end of his nose, and his unruly, moussed buzz cut sprouted in all directions. Presented with the lack of a draft in America and ideas of alternative service such as the Peace Corps, Voronin dismissed any kind of civic service options to the Russian draft. “For me, alternative types of service are almost like an alternative sexuality,” he said. “Normal men serve.”

Last year, Voronin’s office recruited 608 Cossack men from the Rostov region to serve in the Russian army. Of those recruits, about 100 soldiers signed three-year minimum commitments to serve as contract soldiers in the 42nd Motor Division in Chechnya — one of the bloodiest corners of the war.

“Cossacks respect the traditions of people in the Caucuses region. The military is uncomfortable that we have success there and their official troops don’t,” Voronin said of these new contract soldiers.

“We were raised up by history,” said Major Boris Azarkhin, a Cossack military leader. “For modern Cossacks, our main purpose was to protect our country.” He wore a dress shirt with the Cossack crest stitched on the breast: St. George sticking his spear through a dragon’s neck.

Cossack history contrasts neatly with the centuries-old conflict between Russia and Chechnya republics. While Chechens have bucked Russian control since the 19th century, constantly struggling for an independent republic, the Cossacks have maintained a good relationship with Russia since World War II when they fought German tanks with horses, rifles and sabers. The Cossacks lived here as proud Russian citizens for centuries, still maintaining cultural traditions like colorfully embroidered shirts and community holidays. While a tight-knit Cossack leadership council presides over Cossack schools and churches, the ethnic group has always deferred to the Russian government since World War II.

The major proudly insists that his soldiers in the 42nd Division in Chechnya represent “the best soldiers the Cossacks can offer.” He hoped the outpost would grow into a full-fledged, self-contained military community, with schools, parks, and housing projects for soldiers’ families.

“Then the soldiers won’t have any headaches like caring for their families,” he said, “They will only care about serving better.”

These brave sentiments raise some hard questions about occupation. Generations of American soldiers will someday staff precarious bases in places like Falluja or Baghdad, keeping an uncomfortable peace. Iraqi or Chechen insurgents aren’t bound by such defensive positions, and they can hide anywhere in their country.

Occupational outposts are fixed barbwire fortresses, perpetually exposed to mobile attackers. The idea that soldiers’ wives and children could grow up inside these war zones is absurd, even for a culture seeped in militarism as the Cossacks. Nevertheless, insurgencies in Chechnya and Iraq virtually require this sort of decades-long commitment.

Mercenary back-wages

While the Cossack major dreams of a professional occupation force with palatial barracks, in reality, the army has lost too many troops and resources during the Chechen occupation to start afresh. As Colonel Tolmachev explains, education loopholes and bribery have crippled the drafted forces, sending ill-equipped soldiers into a complex battlefield. Professional soldiers seem like an elegant solution, a way to eventually end the draft and fill the ranks with eager soldiers like the Cossack contractors.

However, a few retired contractors painted a grim picture of hired guns in the Russian army. While they wouldn’t speak at length about their service, their assessment was simple: “All army financers are traitors,” said Oleg Gubenko, a former Cossack contract soldier. “They should be shot.”

Gubenko joined the army full of ethnic pride in the late 1990s, but after serving as a contractor in Chechnya for three years, he returned home bitterly without his full pay. Last August, Gubenko organized a strike with other unpaid contract soldiers. Some members of his group alleged that the army owes them upwards of 1 million rubles for their contract service. The matter has not been resolved. As hundreds of new contracts are signed this year, these contractors wonder if it will ever be resolved.

Stanislav Velikoredchanin, a civil rights lawyer whose shaggy beard, tattered shorts and sandals clash with the brazen toughness of the soldiers that he defends in court, reflected on the fundamental issues facing the Russian military in his living-room office. “The main problem in the military is financing” he said. “Anybody would be happy with 15,000 rubles, but they actually get a lot less. The army promised them big money, but many were not paid.”

Velikoredchanin has experience defending soldiers in civil cases concerning owed wages and the intricacies of draft policies. In 1999, he published the book ABC’s for Recruits — a 400-page manual on the loopholes and inaccuracies within Russian draft-law that could be exploited by draft-dodgers. His work helped many young men avoid mandatory service during the troubled years since the war in Chechnya began.

The civil rights lawyer said that the financial problems, troop shortages, and the conflict in Chechnya have changed the army for the worse. He served in the Soviet army in the 1960s, and shares fond stories about his time there. He muses, “Officers used to be noble people. But in times of military action, generals don’t think about quality, they just want more recruits. This fills the army with some bad parts of humanity.”

Despite such criticisms of the draft regime, conservative military analysts do not question the importance of maintaining a standing military force at all costs. Dimitry Tziganok, director of the Institute for Political and Military Analysis in Moscow, placed complete faith in Putin’s military policies — treating the Chechen conflict like a patriotic exercise. While he admitted that current draft laws let too many rich or educated young men escape service, he believed in the idea of an all-inclusive draft.

“The son of a street cleaner and the son of a general should both serve,” he argued. “That’s their duty to their country.”

Leaders like Tziganok see the professional soldier program as a return to the glory days Soviet-era army. However, in the alternative view, Russian soldiers have not changed; their duties have. The drawn-out conflict in Chechnya that has sent many young Russians running from the draft has also sapped the military’s strength.

Contractors may ease some of the problems, replacing scared boys with expensive hired guns, but the policy change avoids a much larger question. In Iraq and Chechnya, new guerillas spring out of the wreckage left behind by occupational forces in these contested nations. This anger perpetually renews insurgency forces, creating an endless demand for more soldiers on the other side, saddling traditional armies with dwindling public support and funding. The question remains for both Russian and United States military leaders: Is it possible to fix an army entangled in a long occupation?

Night falls on Pushkinskaya Street

One lazy night last July, a couple of soldiers mingled with their civilian friends on the sidewalk of Pushkinskaya Street. Street cleaners in orange plastic vests smoked cigarettes in the night breeze. Rich kids parked their squat, black sedans on the sidewalk, blaring American hip-hop out open windows.

A pop ditty played on a transistor radio in a café, a military song that had become curiously popular over the summer. Pop star Leonid Agutin, backed by a rock and roll orchestra, sang:

I must serve like everybody

The train will take us to the border

Cheer up boys, we’re all soldiers now.

The simple song is belied by a complex reality. Every year hundreds of teenagers sneak out of service, Svetlana Arsenyevna Lozhkina collects letters from scared soldier-boys, contract soldiers beg for money, and Cossack soldiers lose the nationalistic fever burning in that song. Still, officials like Tziganok hold on to the stubborn patriotism of that anthem, dreaming of a streamlined occupational force.

As the visible strain on America’s overstretched military stokes rumors of an impending draft reinstatement, the grim reality of Russia’s war on terror might foreshadow the future of America. The Russian military has floundered in Chechnya for five years — and they won’t be leaving anytime soon. This doomed struggle burned out a once-powerful army.

In August, terrorists smashed all illusions of safety and control with a couple pounds of explosives. Insurgent fighters don’t need to build elaborate bases, stage complicated army drafts, or worry about missing wages. They are desperate, and can cripple rebuilding efforts for years. As that plane wreckage tumbled to earth outside of Rostov-on-Don, it reminded the whole world that these are new kinds of wars — wars that no traditional soldier can win.

The song never defined the “border” its boys are rushing to defend. This border might be the frontier between boys and men, street cleaners and generals, recruits in Rostov and politicians in Moscow; perhaps it’s also about that invisible, broken line that once kept war far away from this peaceful street.

As the cheery tune ended, the soldiers wandered down Pushkinskaya Street.

STORY INDEX

This story was written with the support of Elena Gracheva and NYU’s Russian American Journalism Institute.

BOOKS >

Purchase these books through Powells.com and a portion of the proceeds benefit InTheFray

Lenin’s Tomb: The Last Days of the Soviet Empire by David Remnick

URL: http://www.powells.com/cgi-bin/partner?partner_id=28164&cgi=product&isbn=0679751254Resurrection: The Struggle for a New Russia by David Remnick

URL: http://www.powells.com/cgi-bin/partner?partner_id=28164&cgi=product&isbn=0375750231The Haunted Land: Facing Europe’s Ghosts After Communism by Tina Rosenberg

URL: http://www.powells.com/cgi-bin/partner?partner_id=28164&cgi=product&isbn=0679744991

ORGANIZATIONS >

NYU’s Russian American Journalism Institute

URL: http://journalism.nyu.edu/pubzone/weblogs/rostov/Russia’s Military Analysis

URL: http://warfare.ru/Pravda’s English-Language Edition

URL: http://english.pravda.ru/The Moscow Times

URL: http://www.themoscowtimes.com/indexes/01.html

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

The Boiling Point

Some good bombs.

Some good bombs.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

Secret Asian Man

Tsunami relief trickle-down.

Tsunami relief trickle-down.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content