- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

As people across the United States commemorate the Fourth of July with beach trips, fireworks, and barbeques, there is a semblance of unity among people of all backgrounds in this country. We all have a reason to celebrate — not just the United States’ independence, but also a much-needed extended weekend.

Published in the midst of this temporary concord, this issue of InTheFray highlights those who don’t quite fit in, those who are — both literally and figuratively — strangers to the space they occupy and the air they breathe. In Ayesha and me, we see what happens when ITF Contributing Editor Anju Mary Paul attempts to understand the experiences of a young Muslim immigrant. What she discovers about being “American” and being Muslim isn’t what you — or our immigrant-reporter — might expect. The same could be said for ITF columnist Russ Cobb. During a road trip from Texas to California, he confronts the Red State/Blue State divide head-on, only to discover that the 2004 election results don’t tell the full story of American politics.

Across the pond, meanwhile, American transplant Karen Ling discovers a way to compensate for her feelings of inadequacy in Paris — helping American tourists who have an even tougher time fitting in. And in Tofu and toast, Rhian Kohashi O’Rourke explores, through her eyes, what it means to be an outsider for her aging grandfather who has become a foreigner to his own life.

For those who still feel like they belong, Dave A. Zimmerman challenges you to think again. In Everything silly is serious again, he explores how Batman Begins gives us a taste of a comic book character quite different from the one we grew up with. Silly or serious, though, the newest Batman, Zimmerman contends, plants the seeds of truth about our own lives.

Happy reading!

Laura Nathan

Editor

Brooklyn, New York

(Rich Tenorio)

Walk into a comic book convention, and you might be immediately tempted to walk back out. You’ll find yourself in a weird world, with people of all ages engaging in various types of indulgence. Often, this includes fantasies that heroes venerated on the page or in film are actually three-dimensional, tangible realities that they can encounter, or even become. To an outsider, this is silliness taken to the extreme. To an insider, this is serious freedom.

Last summer I went to one such convention, and as I walked around in bewilderment, my eyes finally settled on a young woman dressed from head to toe in a spandex body suit, tricked up to resemble the costume worn by Phoenix (a comic book character who once destroyed an entire universe). She had a gravely somber look on her face, which was appropriate, for Phoenix was about to meet her maker.

Chris Claremont, creator of the character Phoenix and a 30-year luminary in the comics business, was signing his work for awestruck fans. Phoenix was next in line. Claremont motioned for her to approach him, but she just stood there, shell-shocked. The absurdity was obvious — this girl wasn’t even born when Claremont was in his prime, and it’s a comic book, for heaven’s sake, and to top it all off, she’s dressed like an ice skater without the skates. In another sense, this was her moment of epiphany. Her world’s maker was bidding her to come, and such existential moments are hard to come by.

The phenomenon of this grave absurdity extends throughout the comic book universe, even to such comparatively local heroes like Gotham City-bound Batman. With the release of the first Batman film, the comic strip Foxtrot lampooned the seriousness with which comic book fans take their heroes: young Jason Fox and his friend, dressed in Batman costumes and hopped up on comic book trivia, were unwillingly chaperoned by Jason’s brother to the movie’s release. There, they criticized lapses in continuity and celebrated clever innovations in the Batman myth, all while the elder brother hid his head in shame. By the close of the film, however, the brother had been converted and had donned his own Batman costume, greeting Jason with the insanely geeky “Hail, Bat-Brother!”

A similar lunacy was on hand this summer as Batman Begins relaunched the character’s film franchise. Started in 1989 as a gothically quirky spectacle, the character was fueled by his comic book history and director Tim Burton’s imagination. Batman gradually evolved into a camp spectacle under the helm of replacement director Joel Schumacher, and with the release of 1997’s Batman and Robin the franchise was declared dead. Good riddance, said fans, until rumors began rippling that a new movie would feature Christian Bale as star, and Christopher Nolan as director. This film was rumored to bear a closer resemblance to the spooky suspense film Memento than to Rocky Horror Picture Show, and it would rival Fantastic Four, Star Wars 3, and Spider-Man 2 in box office receipts. This was to be the film to resuscitate the dead character. Upon closer inspection, however, it’s clear that Batman hasn’t been dead, but he’s simply been in the midst of yet another cycle — one that begins in dour seriousness, and ends (over and over again) in deliberate silliness.

Consider Batman’s origin: A boy witnesses the murder of his parents. In a vision, he finds his calling in fighting crime, using fear as his principal weapon. He plans to bring justice to a community overrun with corruption — what’s so funny about that? If you take the long view, the answer is… Plenty. This boy has become pudgy, corny, and ambiguously gay, at various points in his career. He has been joined by a Batgirl, a Boy Wonder, a Batmite and a butler. He has bottled Bat-Shark-Repellant and narrowly avoided being burned to death by a giant magnifying glass. How long can we tolerate such radical oscillation in one character, however iconic? How can we justify our long romance with such an unsettled enigma?

Putting the Goth in Gotham

Batman was the second major superhero to find a following in the comic book industry of the 1930s, providing a stark contrast to the bright, flashy optimism of his forebear, Superman. More influenced by film noir and crime novels than by science fiction, he found an immediate Depression-era audience. The early days of comic books met an undefined audience. Batman played to the middle, telling stories that appealed to soldiers, school children and traveling salesmen, and with Superman and other new entries he was soon selling millions of issues per month.

The primary audience was children, of course, and the publisher gambled that adding a child as a principal character would cement customer loyalty. Robin, orphaned by organized crime, came under Batman’s care and soon joined in his adventures. Though his origins were also tragic and dramatic, Robin’s presence gave Batman a fatherly dimension that furthered his shift to the mainstream. Over time, particularly after the war, Batman and Robin were domesticated.

Too close for comfort

The domestic allure of the 1950s is well-documented, providing a monetary channel for post-war affluence and a means of repatriation for soldiers returning home and women exiting the workforce. The American image of the day was security, propriety and general bliss, providing nary a reason to leave the house. The comic book audience was fragmented, with readers attracted to gritty crime stories pilloried by parents desperate to shield their children from harmful influences. Superhero comics settled on an audience of children, which meant that their stories — most notably stories of the Batman — became sillier and simpler, with villains serving more as pranksters than as menaces to society.

The sillier Batman became, the more seriously he was scrutinized. As the 1950s progressed, perceived threats to domestic tranquility became matters of grave public concern. When Frederick Wertham published his 1954 book Seduction of the Innocent, a damning polemic on the harmful effects of comic reading, he scandalized his audience by reporting that some of his adolescent male clients reported homosexual wish dreams based on Batman and Robin.

Comics producers tried to silence the gay reading of Batman. New characters were added, including Batwoman and Batgirl, to suggest heterosexual love interests for both Batman and Robin. Nevertheless, the Wertham revelation signaled the beginning of what might well have been Batman’s end — by 1965 the title was in grave danger of being canceled.

If you can’t beat ’em …

In 1966, however, ABC Television launched the Batman television show, airing twice weekly. Comic book sales surged to their highest levels, and Batman was revived. Rather than fight back against the stigma of silliness and subversion that had sunk the character so low, the television reveled in camp. Bizarre camera angles, outlandish colors and sets, ridiculous dilemmas, melodramatic language, and flamboyant acting made the show the centerpiece of pop television. The program won a devoted adult audience, with kids watching alongside the adults.

Interestingly enough, viewers who would have watched the show as children (myself included) recall not so much the silliness of the program as the sense of adventure that made each episode appointment television. Will Brooker, in his book Batman Unmasked, reflects on his childhood experience:

I didn’t think it was funny when Batman announced that he’d resisted King Tut’s hypnosis by reciting his times tables backwards; I thought it was pretty impressive. . . . As an adult watching the series for this research, I found Batman divinely funny: but I can still very much remember what it was like to idolize the Caped Crusader. (pp. 197-98)

Brooker highlights the phenomenon of the dual audience — adult viewers reveling in the self-mocking humor of the series, set alongside young viewers seeing the full flash and spectacle of a hero in action. The same show that salvaged Batman as a character by lampooning him for adults thus, simultaneously, built a fiercely loyal fan base of young children by showcasing the character’s life of adventure.

Return to the Dark Knight

The camp television show was cancelled after only a few seasons, ending Batman’s romance with the mainstream. In the meantime, the comic book industry had been changing dramatically. Now appealing more centrally to a college-age audience, writing was geared toward issues that interested that demographic. Comic books were telling stories of racial tension, Cold War scenarios, illicit drug use, and cavalier sexuality. Now-adult fans interacted more directly with comics producers than ever before, and the consensus was that Batman is a serious character — not silly. The post-television Batman parted ways with Robin and focused in hard on the crime plaguing Gotham City. Writers Gardner Fox and Denny O’Neil, among others, emphasized Batman as the world’s greatest detective, putting a lie to the TV series’ Batman-as-gadabout and fueling two decades of serious storytelling.

Of course, Batman never really shed his TV image during this time. The 1960s series continued in reruns with its dual-audience formula, and Saturday morning cartoons of various stripes reinforced the image of Batman as a folksy patriarch, complete with Robin and the occasional magic bug named Batmite. Young viewers still took comfort in Batman’s accessibility, and read adventure into the bright colors that characterized his television exploits. But with the retrenchment of the comic book community as a cloistered set of writers and artists, the character’s potential for somber storytelling was mined for all its worth.

Serious-Batman reached its apex with 1986’s The Dark Knight Returns, by Frank Miller. Miller, who later would write the comics that eventually gave us another of this year’s blockbusters, Sin City, took his inspiration as much from the crime-novel genre as from Batman’s history and superhero conventions. Miller starts his fresh take on Batman by introducing us to Bruce Wayne toward the end of his life, as he struggles to retain his sanity, much less his relevance, in a world that has long since buried the Batman.

In his book How to Read Superhero Comics and Why, Geoff Klock highlights the “deliberate misreading” Miller applied to the comic icon: “Miller forces the world of Batman [in all its innate silliness] to make sense” (p. 29). Bruce Wayne has aged to a point never seen by any previous comics writer. Robin has been killed, at some point, but Batman has been pressed into another patriarchal role. This time, it’s by a girl who speaks a barely recognizable English, and who wishes to take up the mantle of the “boy wonder.” Batman’s enemies are portrayed as having intimate knowledge of his psyche, and prove, ultimately, to be closer to him than that other iconic hero of comics history, Superman. The world that died to Batman 10 years prior has become a scary, scary place, and the only humor that enters the story is infused with irony, cynicism and defiance. Batman is not only serious, he is deadly serious.

Deadly seriousness ruled the day in comic writing, however. Alan Moore, who scripted the simultaneous blockbuster The Watchmen as an utter deconstruction of the superhero mythos, wrote about the new gothic home crafted for Miller’s Batman:

Gotham City, a place which during the comic stories of the 1940s and 1950s seemed to be an extended urban playground stuffed with giant typewriters and other gargantuan props, becomes something much grimmer in Miller’s hands. A dark and unfriendly city in decay, populated by rabid and sociopathic streetgangs, it comes to resemble more closely the urban masses which may very well exist in our own uncomfortably near future. . . . The values of the world we see are no longer defined in the clear, bright, primary colors of the conventional comic book but in . . . more subtle and ambiguous tones.

The Dark Knight Returns was met with immediate critical acclaim and consumer enthusiasm, and the Batman film that would launch the new franchise three years later would capitalize on Miller’s brooding vision.

Overexposed

Four films and three Batmen later, the franchise had entirely abandoned Miller’s take on the world of Batman. Gone was the dark, foreboding cityscape; in its place were skateboard ramps, double-entendres and Arnold Schwarzenegger. The cryptic Bruce Wayne portrayed by actor Michael Keaton had devolved into a lovable, bumbling patriarch played by George Clooney. In the meantime, another wildly successful cartoon had entered syndication, and although this animated Batman had some edge to him — no pupils in his eyes and a gruff, utilitarian voice — he was surrounded by the pranksters and silly supporting cast that had characterized stories in the 1950s.

Meanwhile, the grittiness that had entered comic-book storytelling through Miller had diffused from Batman into other storylines, and what had been unique to Batman quickly came to characterize the industry. Specialty shops became lone sanctuaries for proponents of that industry, and comic book readers became laughing stocks in the eyes of the mainstream. The star-studded comedy Mystery Men lampooned not just Batman, but superheroes in general. More broadly, the film mocked the obsession that overtakes fans of superheroes. The capacity for mainstream popular culture to take superheroes seriously had reached its limit, and only fanatics were left to embrace the darker side of Batman and his peers.

Isolating serious readers of comic books in quarantine, however, ultimately incubated some profound storytelling opportunities, enabling a renaissance of the genre, and launching the cycle all over again.

If I don’t laugh I’ll cry

Today’s Batman, in film, on television, and in print, is typically dour, obsessive, efficient and generally unfriendly. He remains so focused on his mission — to combat crime and seek the welfare of his city — that he remains isolated even from those closest to him. He has, as such, become a bit of a laughing stock to other superheroes. Kevin Smith’s 2002 Green Arrow: Quiver features just one of many such interactions:

“With all due respect, Bats . . . anyone ever tell you you’re a weird guy?”

“You’re here to observe, Stephanie. Not to make observations.”

“I know, but c’mon—you find a friend who everyone thought was dead, and instead of throwing him a ‘welcome home’ party . . . or even a ‘Holy Moley! You’re alive!’ party … you knock him out, x-ray every bone in his body, and give him multiple cat-scans. Or do we call ‘em ‘bat-scans’ down here?”

Hyperseriousness in any situation, after all, is itself rather silly. And, in a sense, it’s a little sad as well. Teenaged Robin suffers from Batman’s seriousness as he’s forced to be an ever-vigilant soldier while his friends get to play at recess. Neil Gaiman, author of the acclaimed Sandman series, and no stranger to serious storytelling in the comic format, lamented the loss of Batman’s playfulness using the Riddler’s voice in 1995’s “When Is a Door”:

It was fun in the old days. … We hung out together, down at the “What A Way to Go-Go.” It was great! … You know what they call them now? Camp, kitsch, corny … Well, I loved them — they were part of my childhood.

In response, the genre has expanded the principle of the dual audience to a triple audience. The young are courted through animation, merchandising and age-specific stories and formatting; the adult fanatics are honored with deliberate misreadings of characters in a variety of formats (such as Brian Augustyn’s Gotham by Gaslight, placing Batman in the historical context of Jack the Ripper); and the adult mainstream is guaranteed a laugh, with winks of self-referential humor and with storytelling that acknowledges the silliness of simply being human.

So, for example, the X-Men are represented in toy stores and on the Cartoon Network, they’re reconceived by postmodern storytelling juggernaut Joss Whedon, and they mock themselves in film with jokes about spandex and code names. Films that fail to acknowledge this triple reading, such as 2004’s The Punisher and 2005’s Elektra, are given negative reviews by fanatics and perform poorly at the box office.

Batman Begins offers psychological complexity to the adults, reverent treatment of characters to the fanboys, and lots of toys for the kids. Batman, more so than Superman or any other character, continues to cover the complete spectrum, from silly to serious, with astonishing effectiveness. Moviegoers feel no compunction laughing at the souped-up Batmobile mere moments after weeping for a traumatized young boy.

The fact of the matter is, stories about superheroes, much like stories about all of us, can hardly avoid a simultaneous mix of seriousness and silliness. Fundamentally, after all, stories about superheroes are merely supercharged stories about us. The agony these heroes feel over the wrongs done to them may, from an objective distance, be clearly overdone, but with a sympathetic viewing they can be seen as true expressions of how people struggle through whatever life they’ve been given. With a clear head, we can laugh at ourselves for the ways that we react to others, and yet, we can remove ourselves from our own lives for only so long before we have to deal again with the agony as we experience it. Our pain would be silly if it weren’t so sad.

Authors have clearer sight than their characters — they can see the absurdity and the agony all at once. Authors who have told the stories of Batman and his contemporaries have chosen to emphasize either silliness or seriousness, but virtually no Batman tragedy is told entirely without humor, and virtually no Batman comedy is told entirely without the subtle weight of pain. We can sympathize with Batman even as we’re tempted to laugh, because life itself is such a subtle mixture of tragedy and comedy that we don’t always know whether to laugh or cry. And there — somewhere between the tragedy and the comedy of it all — lies the truth.

STORY INDEX

MARKETPLACE >

Purchase these books through Powells.com and a portion of the proceeds benefit InTheFray

Comic Book Character: Unleashing the Hero in Us All

URL: http://www.powells.com/cgi-bin/biblio?inkey=1-0830832602-0

RESOURCES >

Fan-initiated community page

URL: http://www.darkknight.caBatman Begins official movie site

URL: http://www2.warnerbros.com/batmanbegins/index.htmlAdam West, star of 1960s Batman television series

URL: http://www.adamwest.comFan-initiated chronicles of Batman, 1940s-1960s

URL: http://www.goldenagebatman.com

Hiding inside her apartment leaves the author little room to make faux pas on the streets of Paris.

When the chance to apartment-sit in Paris came up, I finally made the big move. After years of fantasizing about life abroad, I was about take the first leap into my destiny as an international adventuress. That was the title I introduced myself by, for lack of more concrete plans.

I was seduced by the idea of making a fresh start. Being able to say, “I live in Paris,” would render even the act of waking up a little more blessed. (Read: “I’m waking up poor and unemployed in my dingy flat, IN PARIS.”) I harbored the secret thrill of knowing that the fascination most people had for the city would, by extension, leave them in awe of me.

“Living abroad will teach you so much! You’ll turn into a real woman — refined and sophisticated.” My friends and family were swept up in the possibilities of my upcoming journey.

But by departure time, I found myself all knotted up and personal growth the last thing on my mind. My mood dipped from excited to gloomy. I was sure that my first trip to France last summer had sapped the newness of the experience. The clichés had been exhausted. I had visited the monuments touted on the tourist postcards. Already scampered across cobblestones with Gene Kelley enthusiasm.

This time, I would have no friends, no job visa, no plans, just a scary blank slate. With my anticipation dampened by pessimism, all I had left was the dreaded realization: I’m moving to a foreign land, and I have to make it work. My Parisian fantasy went pouf.

Les Halles station, with its hordes of veteran Parisians, can be intimidating for the uninitiated.

Paranoid to patron

After pooling my savings from a series of meaningless jobs and waving a falsely cheerful goodbye to friends and family, I had nothing to do but leave. During the first few weeks of my arrival, I spent days shuffling around the apartment in my pajamas, taking fearful peeks out the window between spoonfuls of Nutella. I didn’t have a problem with Paris or French people, but the risk of being a walking ball of foreign faux pas was daunting. Having taken a year of French in college meant that I should have been able to manage without resorting to “parlez-vous anglais” but fear of conversing in raw, unadulterated French froze me entirely. My only line of defense was shrugging my shoulders and flashing “I don’t understand, please go away” eyes.

Improving my language skills was an emotional process. I would spin around in a mental dance of self-congratulation whenever I got through a conversation without bursting into bright red as I stuttered through the exchange. Unfortunately, I wasn’t masochistic enough to willingly humiliate myself on a routine basis. The amusement as well as flashes of impatience in response to my mangled pronunciation held fast in my memory and deepened my diffidence.

I poured over guidebooks on French culture but made a general effort to avoid social situations. Food markets were picturesque in books but made my anxieties flare. How should I ask for unlabeled items? How could I explain to the fruit lady that I hadn’t understood her well-meaning advice on figs? I avoided the fromagerie and bucherie for similar reasons and resorted to impersonal packaged food from the supermarkets. Instead of practicing my French, I practiced making myself invisible to ward off looks of pity.

Meanwhile, the ordeal of keeping in touch with friends and family back home had taught me that evasion is the best policy. In principle, email updates from abroad should include a generous dose of “What I’m up to,” with a subtext of, “Don’t you wish you could be here?” or more subtly, “don’t you wish you could be me?” Contrary to what people back home expected, I refrained from gushing. I hoped they would interpret the lack of news with a little misguided imagination and enthusiasm. If they would only try a little, they could imagine me coiffed and chic, romanced by a dozen chain-smoking young Europeans over an assortment of croissants and paté.

I was tempted at times to pack up and leave but failure was more frightening to me than staying in Paris. The little voice in my head whispered “and what would folks back home think if you were to give up?” So I parted with some of my precious savings for daily French lessons. After two mundane hours in morning class, I got to hang out in the school cafeteria with an international cast of women who also had complexes about being in France. Our lunchtime conversations covered everything from the confusions of life abroad to job search tips.

But more than language lessons, what really turned things around was the don’t-have-a-clue state of some anxious tourists. Two months into my stay, I was in a grocery store on the Champs-Elysées, strolling up and down the biscuits aisle when my reverie was interrupted by the raised voices of confused Americans. A couple was struggling to get assistance from overworked cashiers in no mood to straddle languages. I shook my head, knowing from my French culture guidebooks that substandard service was a cultural norm and that speaking in English only made things worse. In an act of compassion, I swept the tourists under my protective expatriate wings.

The source of their confusion was in the range of electrical outlets. “We don’t know which one to pick. We don’t want to risk exploding our second cell phone as well.”

“You won’t find what you need here,” I told them authoritatively. “You have to go to the 12th district, full of computer shops. [But] no one will understand what you are talking about and will send you away. You’ll need to head to the one just a bit off, by the river.”

“Ah merci, merci! Do you have a name?” they asked, tearful with gratitude.

“No. And if you find the right plug, it will cost you a lot of money.” I walked away with the glow of one who had done good. My assortment of embarrassing mishaps had allowed me to accumulate what could be interpreted as Important Information. For the first time since arrival, I was able to demonstrate competence, at least in relation to those more clueless than I — the people who felt even more stranded and scared in this country. Suspecting that this could hold the key to a greater truth, I decided to make it my duty to sniff out tourists in their moment of desperation and come to their rescue.

Another day, another tourist in need of assistance.

My most memorable damsel/victim was a little balding man stranded in the Metro’s maze of underground tunnel. Shoved by the rush of afterwork passengers, he looked ready to cry. “Vous avez besoin d’aide?” I asked him, then tried “Um, do you need help?”

“Thank goodness, someone who speaks English!” said the tourist, who turned out to be from Kentucky. He explained that he had been following his tour group through the station for a metro change, had paused to give some money to musicians, and when he looked up, the group had disappeared. “The tour guide was taking us to a pizza place. Somewhere south, I think.” He didn’t have the name of the restaurant or the metro destination. “Maybe a taxi driver would know of a pizza place south of here.” I stared at him, amazed and I must admit, exhilarated at his naïveté and childlike carelessness.

He thought it might be easier if he just returned to his hotel, but he had forgotten the name: Hotel Est, maybe, or Est Hotel. He sifted through his pockets, but found no address or phone number among the wads of American dollars and euros.

We spent a quarter of an hour at the information booth where the attendant with the Yellow Pages fruitlessly read out the names of 20 hotels containing the word “Est.” Mr. Kentucky then went through his pockets again, this time yielding, to the disbelief of me and the attendant, two business cards from the hotel.

I didn’t get irritated. Because as much as this guy was a nuisance, I found that I needed him and all the other helpless tourists just as they needed me. I hoped that he, and the others who in their moment of confusion mistook me for a local, returned home with a memory of me as some kind of French guardian angel. A Good Samaritan who had helped them at their most vulnerable moment without disdain or ridicule.

I had spent months trying to shrink away from life abroad, but my newfound ability to save other sufferers injected optimism into my Parisian travails. I allowed myself to see that after incessantly analyzing French culture as an outsider, I had somehow accepted and internalized some of its more foreign elements. As I grew to see my new culture for what it could be, I was finally able to take off my cloak of invisibility. I felt like I had grown just a little more competent at fitting in; well on my way to international adventuress status.

The island filth is clingy and stubborn. It’s an all-out war between me and the layers of Hawaiian dirt that have accumulated on termite-eaten walls. My mop lunges violently at the house that my grandfather built 50 years ago. The aging paint crackles and chips, as bubbling cleaning agents do their grimy work.

Droplets of sweat accumulate on my forehead as I toil away, but I mistake my perspiration for Hilo’s perpetual ocean spray. The air is so moist that some mornings I return home soaked from a run, not realizing that my clothes have been saturated by a gentle morning drizzle.

I take a break under the lines of fruit trees that Grandpa planted in front of the house’s entrance. Mom says that wherever Grandpa walks, vegetation pops up behind him — a green thumb I failed to inherit. For years he nurtured the earth daily so that he could leave us the gifts of his land. Lemons the size of oranges, oranges the size of grapefruits, star fruits, crunchy green mini-apples, and chubby berries wait to be plucked. I sink into the earth’s moistness, my toes slipping out of my slippahs and into papaya mush.

I start clearing rotting branches, fallen leaves and decomposing fruit from the black gravel ground and feel a wave of distress — Grandpa can no longer look out his living room window and watch us as we enjoy the fruits of his years of labor.

The disturbing images of the nursing home video I watched a month ago flood back as I remove mildew that has crept across the walls. “Don’t feel guilty about condemning your elderly loved ones to a cold, windowless home for the dying, where we are understaffed and unhappy,” was the message I took away. Viewing this video at home in the D.C. suburbs, 10,000 miles away from my grandfather’s nursing home room that he shares with a new person (his last roommate passed away), I shudder imagining his life.

He is lying on his back, developing skin sores behind his knees, elbows, and calves because of the constant contact with unfriendly plastic sheets designed to protect the bed from his incontinence.

There is no soul-warming miso soup, with little pieces of tofu and green onions floating on top. No soft, steamy white rice that can dissolve under his toothless gums. Instead, the hospital staff leaves huge chunks of “all-American” white toast that neither his shaky hands can cut nor his gums can manage.

Grandpa’s second-stage dementia triggers a series of daytime naps — the Wonder Bread, left beside his bed, goes stiff and is cleared away before he wakes. On their clipboards, the hospital staff note that he has no interest in eating. He slips in and out of reality, not knowing how or when to ask for food. His remedy? Singing his empty stomach to sleep.

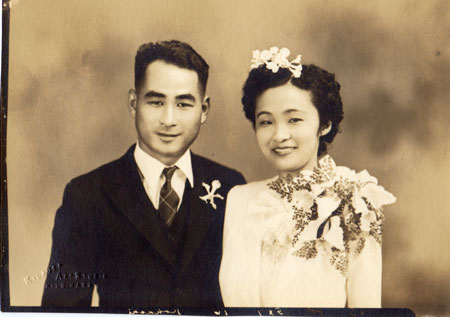

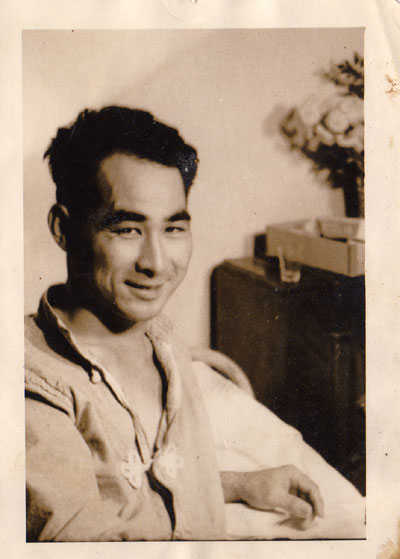

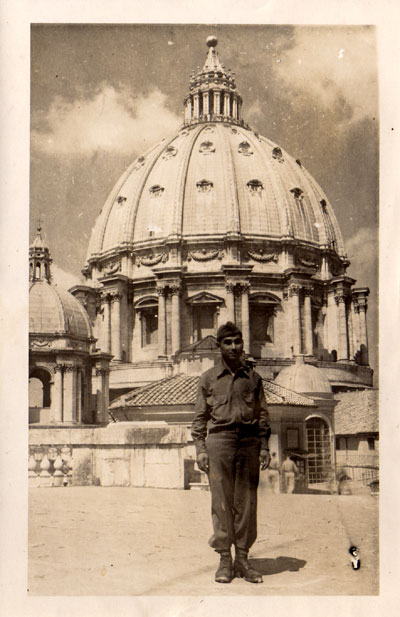

The songs he and his 442nd Purple Heart buddies used as their sustenance during WWII, serve as his now.

“Oh, but Grandpa Kohashi is doing just fine! He watches the birds every day!” the nursing home’s public relations employee tells my mom during a long-distance phone call.

“The birds, the birds — all they can talk about is the birds!” my mom mutters to herself as she hangs up, feeling helpless from the East Coast. “Can’t they comment on his health? His eating habits? His adjustment?” I see guilt emerge in tight wrinkles on my mother’s face. Scrawled on our kitchen calendar are X’s marking the number of days left before we fly to visit him.

And now here I am, in Grandpa’s hometown of Hilo, trying to protect and cleanse his house and the only piece of land I have known throughout my nomadic childhood. It is the plot that has sustained my struggling immigrant family for four generations. Its cement structure has proved impenetrable — withstanding tropical storms and the 1960 tsunami that claimed the life of my mom’s elementary school classmate only a few homes away.

Grandpa’s name tag says, “My name is Hiroshi ‘Coffee’ Kohashi, and my favorite hobby is building my own house.”

I imagine Grandpa pouring wheelbarrow after wheelbarrow of cement into a foundation that would keep for future generations — it was a symbol of the unlimited possibilities for success.

“Are you Susan’s son?” my Grandpa asks my brother. His capacity to recognize our hapa haole faces has disappeared, and so has our opportunity to make him proud. I want to tell him that the reason my younger brother is studying biomedical engineering is that Grandpa inspired us to work everyday, to chip away at our goals until they no longer appear frightening to achieve.

I squeeze his withered hand and peer into his glazed-over eyes, realizing that they never read the postcards I have been sending him for over two years during my travels, tiny acts of gratitude for every achievement I owed to his silent support.

“Hey, take it is easy!” my mom yells out, as she hears paint splintering and ripping off the wall’s surface. I try to refocus and resort to my old childhood game of pretending to be the Karate Kid diligently painting fences white and waxing cars smooth for my Sensei. If the main character, Daniel-san, could follow a path inward and heal himself through the repetitive cleaning motions, I can do the same.

I whisper thanks to Grandpa’s cement walls knowing they will hold his history, our history. The now gentle, circular strokes remove stains, cobwebs, and the coating of neglect. I finally step back.

Stripped clean, the raw white surface now shines like a fresh coat of paint.

STORY INDEX

PLACES >

Hilo, Hawaii

URL: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hilo,_Hawaii

GROUPS >

442nd Infantry

URL: http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/agency/army/100-442in.htm

EVENTS >

1960 Hawaii Tsunami

URL: http://www.pdc.org/tsunami_history.php

MOVIE >

The Karate Kid

URL: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0087538

Almost every store along the stretch of Coney Island Avenue that runs through Midwood is Pakistani. From the Khoobsurat Beauty Salon for women, to the K. Prince Barber Shop for men. Then comes Zoha Money Transmitter, where you can exchange your Pakistani rupees for U.S. dollars or vice versa. Subhan Sweets and Tikka Restaurant is a good place to buy a cup of freshly brewed, milky, cardamom-flavored chai but not coffee.

The first sentences Ayesha ever typed into a computer were: “My name is Ayesha ayobe. I am 21 age.”

Over time, in bits and pieces, she told me more about herself:

“I come from Lahore, Pakistan one year.”

“My father work in chicken burger restaurant. My mother no work.”

“My brother Abdul 17 work in grocery store. My next brother Mohammad is 13 age in sixth grade. My next brother Usama is 5 age. He stay home with my mother.”

“My sister Aleena 16 no go school.”

“I no want to marry. No shaadi; single good!”

“I like America.”

There are Muslim women who come to America, live here for years, raise children and grandchildren, and never learn more than a few words of English. There are Muslim women who end up knowing no other woman (let alone man) in this country who is not a family friend or relative. I met Ayesha when I was looking for these women.

At first, I assumed Ayesha satisfied all of my easy categorizations about Muslim women. I saw her as representative of the many young Muslim women who come to America in their late teens and early 20s, too old to enroll in public school and be introduced, through American classmates and teachers, to American ways of life. As a result, they remain trapped at home, waiting to be married off by their families.

I eventually learned that Ayesha was not the stereotypical Muslim woman I had imagined: veiled, docile, and submissive. She clandestinely rebelled against the restrictive world her parents wanted her to live in, making secret forays to the life outside. That is why I have changed her name and those of others in her story: to protect Ayesha from the repercussions that will undoubtedly follow if the truth were to get out within her orthodox community.

But Ayesha also rebelled against the walls that I tried setting up around her, in my attempt to maintain a “proper” reporter/subject distance. And that is why I am no longer in contact with her.

“You are my best friend!”

I met Ayesha at her very first computer class, held on a cold February day at an immigrant outreach organization in the Midwood stretch of Brooklyn. Three times a week, half a dozen women in headscarves — some recently arrived from Pakistan, others from Bangladesh, Yemen and Morocco — turned up at the organization’s office to learn basic computer skills.

At the start of that first class, the instructor asked his all-female, all-non-English-speaking, all-Muslim audience to log into their computers by typing in the password, OPTO. Ayesha didn’t know what a password was so she just sat in her place: a short, stocky, square-jawed woman dressed in a beige headscarf and faux leopard fur coat. Sitting behind Ayesha, I sensed her confusion and told her in English that she needed to type out the word “OPTO” into the computer.

She didn’t move and continued to stare at the computer screen in front of her.

I told her roughly the same thing in Hindi. “Computer meh O-P-T-O likho,” and then she got it.

Once logged on, Ayesha turned around in her seat and told me in Urdu that she was “bahooth khushi,” very happy, to have met me.

Later that same day, she told me, “Aap tho mera best friend hai!” You are my best friend!

“I am go to school.”

Besides studying the computer, Ayesha also took English as a Second Language classes at the community center. During her ESL lessons, Ayesha was always volunteering to read out loud or answer a question, and she completed the simple in-class exercises with only minimal mistakes.

“Make sentences with the words car, bird and school,” the instructor would write on the chalkboard.

And Ayesha would write:

“I have car.”

“I like a bird.”

“I am go to school.”

Ayesha was, in fact, one of the better students. Unlike the other women in her class, Ayesha had studied until 12th grade in Lahore and had learned to read and write a modicum of English.

With computers — because she didn’t have one at home, had never used one — Ayesha was more diffident. But she was also impatient to learn more. (All the women were.) She became angry with herself whenever she made a mistake. She would go, “Oh!” in frustration and smack her forehead with the palm of her hand or rest her head on the top of the keyboard. And whenever she got fed up, she had no qualms saying so to the instructor. She’d switch off her computer monitor, stand up, and announce simply, “I go.”

When she wasn’t in class, Ayesha would be busy with household chores and other tasks. “This weekend, I am cooking, I go to shopping at Bobby’s Store, I go to work,” she would say when asked to list her weekend activities.

Ayesha’s work involved conducting Quran classes in the homes of many of the Pakistani women in the neighborhood. Last time I checked, she had seven students. Other days, she would visit her friend Sana’s apartment on Newkirk Avenue.

Within a week of knowing her, I decided that Ayesha’s was the story I wanted to write.

I started actively courting her in order to ingratiate myself into her good books. I played down my Indian roots in case she was an India-bashing Pakistani nationalist. I didn’t mention that I was Christian. I brushed up on my Hindi. I taught her how to use the Shift and Backspace keys on the computer. I translated unfamiliar English words into Urdu for her.

It was hard not to admire Ayesha’s determination to ease what was surely a difficult adjusting process coming from Pakistan to the United States, and I wanted to help wherever I could.

I had gone through a similar ordeal when, at the age of five, I had left India with my family to move to Scotland. My older sister and I were the only Indians in our all-white Edinburgh public school. My sister, who already knew some English, had thrived; I, who could not speak a word of English, had been terrified. Not knowing how to handle a knife and fork in the school canteen, being teased by older students in the girls’ toilet, getting lost inside the school and being too afraid to ask for directions: everything was a nightmare.

As a fellow immigrant, I wanted to help Ayesha and if doing so meant that I was simultaneously helping myself get a story out of her, so much the better. It meant that my disinterested reporter status would be eroded slightly as I became chummier with Ayesha but I thought I had our relationship under control.

The following week in the middle of computer class, Ayesha turned around and told me, “Today, you come my house.”

Ayesha loves watching Bollywood flicks. Her current favorite movie is Raaz, a psychological thriller that also includes some steamy song-and-dance routines between the hero and heroine.

“There’s a special word: fob.”

To reach Ayesha’s apartment building from the community center, you have to travel a few bus stops up Coney Island Avenue.

Inside bus B68, it was standing room only. Russian grandmothers holding tight to their shopping bags brushed shoulders with Chinese mothers carrying infants on their laps. Together with old Hispanic men and one young Hasidic man, they occupied the seats in front. The back of the bus was filled with African American schoolchildren chatting and laughing loudly.

Ayesha, her younger sister Aleena, and I were the only South Asians onboard. We stood in the aisle — the surreptitious focus of 20 pairs of eyes — and I wondered if everyone assumed I was Muslim the way Ayesha and Aleena in their headscarves obviously were. I felt the urge to distance myself from the two girls.

The truth? Ayesha embarrassed me. Not because of her religion or her nationality but because of her lack of fashion sense.

In my interviews with first- and second-generation immigrant children in Midwood, time and again, the isolation a newcomer child faces when he has not yet learned how to blend into mainstream culture was raised. The teasing comes not just from white or black kids but also from other immigrant children. “There’s a special word people use: fob,” Reshmi Nair, the American-born daughter of Indian immigrant parents, explained to me. A fob was someone “fresh off the boat”, an outsider, not yet “with it”, and therefore very uncool.

Assimilation — the goal of any child who wants a peaceful school experience — meant dressing a particular way, speaking a particular way, knowing what to talk about. I’d learnt that lesson the hard way in Scotland and I’d spent the years since making sure I would never be identified as an outsider again.

Then along comes Ayesha with her monstrous leopard fur coat, her lack of English conversation, and her lack of New Yorker disaffection on public transportation, screaming out her fob status. As a topic she fascinated me, but as a person, she was not someone I wanted to be associated with. I had reverted to a high school hierarchy where the “cool” kids did not want to mix with the “uncool” kids.

And why did Ayesha want to associate with me? Was it really just a simple case of friendship-at-first-sight? Or did she too subscribe to the same high school mentality where, by hanging out with ‘cool’ me and my designer wool coat, she would become more like me?

“In Pakistan, it is very dirty.”

Ayesha’s apartment was in a brick-fronted building that fronted Coney Island Avenue. We entered a dimly lit hallway that had paint-splattered walls and empty paint cans abandoned by the chipped wooden staircase. What little light there was in the corridor managed to come through dirt-encased windows in the stairwell. There was dust everywhere.

The girls’ home on the second floor was tiny for a family of seven. The front door opened into the central kitchen-cum-dining-cum-living room from which two bedrooms led off. Queen-size mattresses rested on the floors of both bedrooms and in the corner of the living room. One of the bedroom mattresses was for the parents and the youngest son Usama, another for the two girls, and the living room mattress for the two older boys. Clothes hung on twine strung across one of the bedrooms.

An English language textbook in Urdu was sitting on the dining table when I entered. (I learned later that Ayesha’s mother used it to teach herself English.) In a glass-fronted cupboard against a wall, various mismatched plates and crockery were stacked. Inside, I spotted a set of Corelle plates. The ones with the brown butterfly motif around the edge. The same ones my mother has back in India. Every upper middle class Indian housewife, who has visited the United States or has relatives here, owns at least one of these Corelle plates. Did the same rule apply to Pakistani housewives, I wondered. If yes, then this would mean that back in Pakistan, Ayesha’s mother would now be considered middle class.

I asked Ayesha’s mother if she liked the United States and she nodded her head vigorously.

“Pakistan meh, bahooth gundhi hai,” she said. In Pakistan, it is very dirty.

Recalling India’s slums and could understand why a person would want to escape that life. Ayesha’s Brooklyn apartment, while overcrowded and ramshackle, was at least clean.

With familiar South Asian hospitality, Ayesha’s mother insisted that I sit down and do nothing while she and her daughters prepared lunch. A Danish butter cookie tin filled with dough and another tin of wheat flour appeared and she started to roll flat the dough into chapattis, the round wheaten bread common to Pakistan and North India. Ayesha cooked the bread over an open flame on the stove and when they were done, stacked them onto a plate and rubbed butter on them. Leftover curries — channa (chickpea), vegetable-and-potato, and beef — from the day before were heated up in the microwave. The curries joined a plate of cucumber slices sprinkled with lemon juice, and a bottle of mango pickle.

As the food was being prepared, I played with Ayesha’s brother, Usama, still in his pajamas at 1:30 p.m. Usama wordlessly showed me his plastic lizard, his helicopter with only one of its blades remaining, and his rubber monster mask. He showed me photos from his last birthday, his first in the United States. The photos had been taken in the apartment and showed Usama and his family, all dressed up in their finest, standing stiffly before the camera, all slightly out of focus and misaligned.

“Why doesn’t Aleena go to school, Aunty?”

Ayesha had removed her coat and sweater, as soon as she stepped into the apartment, losing bulk as she did so. Next she removed her headscarf, letting her hair loose. It was a shock to see Ayesha’s hair, so long that the ends brushed the top of her wide hips. And her face, now that it was no longer framed by her scarf, looked softer and less masculine.

Everything about Ayesha changed once she was home. All her hesitation dropped away and her oldest-child confidence came rushing to the fore. As she spoke to her mother about her day, her voice took on the assurance that comes from talking in your mother tongue to someone who understands you completely. There was even a hint of bossiness in her tone as she ordered her sister Aleena to wash the dishes and lay the table.

Aleena was as shy and withdrawn inside the apartment as she was outside. She hardly spoke, whether in English or Urdu. She could write “My name is Aleena” on her own. They were about the only English words she seemed to know. She once wrote in my notebook – “im 16 years olD. I live in BrooKLyn.” – but only after I spelt out each word for her. In ESL class, she never completed (let alone understood) any of the exercises she was assigned; her sister did them for her when the teacher wasn’t looking.

I had once asked Aleena if she wanted to attend school in America but she shook her head, whispered no, and smiled guiltily at me.

In the apartment, I broached the topic once more.

“Why isn’t Aleena going to school, Aunty?” I asked the girls’ mother in Hindi, fully expecting a harangue against the loose morals fostered by the American public school system. And what use would an education be for a girl who was going to become a housewife anyway? But she nodded her head vigorously at my question and replied that yes, Aleena should be going to school but didn’t want to.

Aleena smiled guiltily once again. Suddenly, the situation seemed more about a young girl frightened by the prospect of change, rather than overbearing parents refusing to give their daughter the benefit of an education.

Ayesha added that it was difficult to talk to the school officials and asked if I would go with her to the school one day.

For a split second I hesitated, worried once again about journalistic detachment and the dangers of getting too involved with my subject. But then I said, yes, of course I’d go.

Ayesha’s new computer takes pride of place in the central kitchen-cum-dining-cum-living-cum-bedroom. Each month, as the family makes a little bit more money, new appliances fill up the apartment: a blender, a DVD player, a printer.

“Why you no come COPO?”

That was when the tide started to turn. From my shadowing Ayesha, it became Ayesha hounding me. It was no longer clear who had chosen whom, and who was the project.

When I didn’t show up for ESL or computer class, Ayesha would call me on my cell phone to ask what had happened.

Over weekends, she would call me using her boyfriend Yusof’s cell phone. Yusof, a 20-something Pakistani janitor working in Manhattan, was Ayesha’s third boyfriend. She would tell her mother that she was going to work, then met up with Yusof instead. Sometimes he would take her on the Q to downtown Manhattan for an afternoon in the city.

Ayesha would call to tell me that she was in Manhattan with Yusof. There was an unspoken suggestion that I should meet up with the two of them. We never did but I knew that if I continued to visit her in Brooklyn, it would only be a matter of time before I would have to invite her to my Greenwich Village apartment in return. Then Ayesha would have gained entree into my world.

A few weeks later, Ayesha called me again to tell me that her family had bought a computer and asked for help setting it up. Unfortunately their “new” computer turned out to be not so new and had no accompanying software or dial-up service. But Ayesha wanted to email. Email Yusof, I imagined. I explained what she would need to do before that could happen.

Then Ayesha asked if I could help her sixth-grader brother with his homework. So I stayed a while longer, going through Mohammad’s assignments with him. As I finally prepared to leave, Ayesha asked me to come again soon to have tea with her family. I couldn’t say no.

Somehow or other, Ayesha had taken over our reporter-subject relationship and revised the terms of our engagement. She had made herself a fixture in my life rather than a once-a-week anthropological experiment. She wanted me to become her computer technician, interpreter of official letters, Manhattan tour guide, and teacher. As she’d said from the beginning: her best friend.

I started avoiding her calls. When she did catch me unawares, I made up excuses as to why I was no longer attending the computer and ESL classes or visiting her home.

Yusof started calling me too, even when Ayesha wasn’t with him. I avoided his calls as well. When he finally got through, he told me that he and Ayesha were no longer an item. She had been double-dating and he had broken up with her as a result.

The next time I talked with Ayesha, I learnt that her new boyfriend (of a month) was the owner of a CD shop in Midwood, a 30-something Pakistani named Firoz. Firoz was a catch but once again, her parents didn’t know about her latest boyfriend. When her parents went out, leaving Ayesha at home alone, she would sneak Firoz into the apartment. She gave Firoz my cell phone number and had him call me from his shop, inviting me to come over for free CDs. I pleaded overwork and lack of time to avoid going down.

Eventually, Ayesha got the message and stopped calling.

Looking back now, I understand that Ayesha was trying to use me to reach out and grab at her version of American life: freedom, fun, learning, and independence. To me, living in America meant looking like an American. But for all my designer clothes, I think Ayesha’s idea of America was better than mine.

STORY INDEX

ORGANIZATIONS >

South Asian Women’s Organizations in the United States

URL:http://www.sawnet.org/orgns/#Pakistan

I set out in late May on a leisurely journey to the American West by car. Among other things, I wanted to witness first-hand the political reality of Red America — a reality I don’t often confront in the blue isthmus of Austin, Texas. My journey started in Austin and ended up in San Francisco, two cities known for their liberal inclinations, though neither is far from Republican strongholds. Austin and San Francisco are both high rent, hip towns populated by a lot of people that fit my demographic — young, white, college-educated liberal Democrats — who, truth be told, have little interest in penetrating the mentalité of the conservative heartland.

As New York Times columnist David Brooks might say, they’d rather vacation in Tuscany than Tucson.

Red America shouldn’t have been such a mystery to me. After all, I grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma, a place John Gunther called “the most conservative city in America,” in Inside USA. Tulsa is the kind of place where the first question people ask outsiders is “What church do you go to?” Voting Republican is not something you decide to do out of free will; it’s a civic obligation, like getting a library card or picking up litter.

Still, the shock of the November election remains with me. Even though I grew up with them, and count of them as family members and friends, I still wonder: Who the hell are these people who reelected George W. Bush?! If, as Thomas Frank claims in What’s the Matter with Kansas, Americans are suffering from a “species of derangement” that allows them to vote against their own best interests, what does this derangement look like on the ground?

This is my travelogue of the people and places of the Red Sea:

Somewhere around Mason, Texas, the inevitable happens. I have been listening to the Austin-based NPR affiliate, KUT, when the crackle and hiss of the weak signal becomes unbearable. I push the dial further to the left, hoping to hear more about the scandal of the day, the “Downing Street Memo,” which supposedly proves that the Bush Administration was attempting to “fix” intelligence to support the invasion of Iraq in 2003.

After weeks of ignoring the memo, journalists were starting to pay attention. The memo was the “smoking gun” that proved the Administration had deceived the American public in the run up to the war.

I listen for more, but no luck. Monopolizing the left side of the dial is what sounds like a college rock band, with a low-fi sound and a jangling guitar riff. When I listen closely, though, I hear earnest lyrics about Jesus and the young rocker’s personal relationship with the Lord. It is “alternative Christian,” a bizarre palimpsest of the Pixies or Nirvana, but with saccharine lyrics about being reborn in Christ.

I push the dial rightward, hoping to get another slice of the airwaves — maybe more on the Memo. Here I encounter Toby Keith, a fellow Oklahoman who has his own take on international affairs. In a song called “Courtesy of the Red, White, and Blue,” Keith warns “the terrorists” (whoever they are in west Texas) that he will personally “put a boot up your ass / it’s the American way.”

AM radio isn’t much better: Rush offers predictable rants about Hillary, Hannity vents about liberal judges, and a particularly vile shout show host named Michael Savage offers his $1.02 about “politically correct” professors. Nothing about Downing Street.

In the afternoon, hunger overtakes me. I am in the vicinity of Llano, Texas — pronounced “Laan-ah” by locals — and the world famous Cooper’s BBQ, so I make a detour. I once read a book by Larry McMurtry in which the Texan said that he would drive 100 miles for a good steak, so I figure a half-hour’s detour for the thickest pork chops ever carved from a pig is worth the trip.

Cooper’s has approximately seven 20-foot-long rows of BBQ pits that smoke every conceivable kind of meat: sausage, brisket, chicken, turkey legs. I think you can even get ostrich. You point to the meat you like, and a huge man in Wranglers pokes it with a sword-like instrument, dips it in some sauce, and then throws it on a plastic tray. If you get your food to go, the good people at Cooper’s put it in an over-sized cardboard box — the kind that liquor stores often use. They encourage you to take an entire loaf of white bread, a 20-ounce Styrofoam cup of beans and a roll of paper towels — for free! It is all excess and dressed-down decadence: what Texans like to call “Texas-sized.”

It is also wasteful and inefficient, of course, but to call attention to the vast amounts of waste generated would come off as un-Texan, and by extension, un-American. A pickup truck in the parking lot has a bumper sticker that reads: “Piss off a liberal: Be happy!” Some eating establishments might be wary of offending patrons by announcing their politics, but Cooper’s has a Bush/Cheney bumper sticker affixed to the front door.

Two pounds of pork chops later, I am back on the road. Long stretches of nothing. Dusty, low-slung towns. Few people visible outdoors, apart from Mexican construction and lawn workers. Even as I write this, I sense something’s wrong with my observation. Texas is now a “majority-minority” state and Hispanics are the largest minority, so of course I would see a lot of brown-skinned folks. It’s just that I don’t see any white people. That’s not a problem, of course, but as I approach the border, I see bright blue “Viva Bush” yard signs. My stomach churns pork.

Contrary to popular belief, a handful of counties outside of Travis (where Austin is located) voted for Kerry last year. Most are along the Mexican border. About seven hours west of Austin, I am in one of these counties: Presidio.

The county seat is Marfa, home to just over 2,000 people, but disproportionately famous for at least three reasons. One is a bizarre phenomenon known as the Marfa Lights, mysterious lights that flash on and off near a distant mountain range. Another Marfa attraction is the Paisano Hotel, where James Dean stayed while on the set of Giant, his last movie. Still another is the work of minimalist artist Donald Judd, who took over an abandoned Air Force base and converted it into a permanent art installation. The installation also houses an artists’ colony that attracts artists from around the world. At the Marfa Book Company, a sleek, cool downtown coffee bar/bookstore, I hear German and Australian accents.

The influx of artists has an odd effect on the locals. Down a side street, I spot an old white church that has been redecorated to look a cross between a Las Vegas-style wedding chapel and an artist’s studio. Pure kitsch. As I get out of the car to snap a photo, an old cowboy in dusty jeans, cowboy hat, and western shirt, nods to me. I am sure I have committed some faux pas.

“Hey, why don’t you take a picture of this?” he says, pointing to his scrappy house and rusted-out pick-up truck next door.

We talk and I find out he is the ex-sheriff of Presidio County, and — surprise — a Democrat. Now he works part-time as a cop in Marfa. Contrary to the stereotype of a redneck, he embraces the artists.

“As long as they pay taxes, let them do what they want. It’s good for a little town like this,” he informs me.

Outside of Marfa, and all along the New Mexico/Arizona border, I see more green U.S. Border Patrol SUV’s than civilian cars. I take two-lanes as close to the Mexican border as I can get. Twice — once in Texas and once in New Mexico — I see billboards spray-painted “The Minutemen.” The border feels militarized and eerie. It is blazing hot, and there are no signs of life except for the occasional torn piece of clothing on a barbed wire fence, probably left by an immigrant suffering from heat exhaustion. I begin to worry about breaking down: there are no towns for 50 miles and no cell phone signals.

On the way to California, I see sprawling towns all along the border that lack any visible water supply: El Paso, Las Cruces, Yuma, El Centro. Theses are booming places that feel part Mad Max, part Bed, Bath, and Beyond. Cruel, lifeless places that look like upscale versions of Falluja.

But the biggest surprise is that, in the middle of this blighted Red Sea, there are signs of life. Flagstaff and Tucson in Arizona. Santa Fe, New Mexico. Here I see people actually walking. Flagstaff, I read in the local paper, is resisting the invasion of a Wal-Mart Supercenter. Santa Fe, for all its hokey New Age vibe, has a unique character. I see more Subarus (the most popular car for Democrats) in Santa Fe than anywhere else in the country.

Days later I arrive in Las Vegas, a place I hope to never see again. This where the American species of derangement becomes a virus, making people look and behave like they’re on a Fox reality show for the living dead.

After four days of traveling I finally feel the cool breeze of the Pacific. I have come up from California’s Central Valley, a flat place of urban sprawl, smelly farms and unbearable heat. Another Red space.

On the horizon, I spy the red Golden Gate Bridge and thank God that the sky is still blue.

I think I’ll fly next time.

STORY INDEX

The writer

Russell Cobb, InTheFray Assistant Managing Editor

“Europe is no longer Europe, it is ‘Eurabia,’ a colony of Islam, where the Islamic invasion does not proceed only in a physical sense, but also in a mental and cultural sense. Servility to the invaders has poisoned democracy, with obvious consequences for the freedom of thought, and for the concept itself of liberty,” is how Oriana Fallaci characterizes what she perceives as the decline of Europe into the grabby and presumably immigrant hands of Muslims encroaching on her continent.

It may be hard to believe that such immoderate and inflammatory rhetoric is in fact a defense of her recent book, The Force of Reason, which in turn is a defense of her previous book, The Rage and the Pride, which was written in response in the September 11th attacks, but Fallaci is hissing out her defense for all it’s worth. Fallaci now faces a trial and potential imprisonment for her diatribe in her native Italy on charges of vilifying Islam; ailing with cancer but still snarling in New York, Fallaci has stated that she refuses to attend her upcoming trial.

Two countries in the world now offer gays and lesbians equal rights when it comes to marital union: Canada and Spain. Tuesday, Canadian lawmakers approved a measure that legalized same-sex marriages throughout the country. Today, Spain’s parliament followed suit.

Unlike similar measures in the Netherlands and Belgium, where gay marriage has become legal but same-sex couples possess a second-class status without the full range of rights that their straight counterparts enjoy, the legislation in Canada and Spain redefines the institution of marriage so that it applies to all couples, regardless of gender. In fact, as The New York Times noted, the Spanish measure adds just one sentence to the existing marriage law: “Marriage will have the same requirements and results when the two people entering into the contract are of the same sex or of different sexes.”

(Yes, one sentence is all it took. And now Canada and Spain don’t have to deal with all the added bureaucratic paper-shuffling and color-coding that this “civil union”/“marriage but not real marriage”/etc. tomfoolery entails.)

The two gay marriage proposals beat back determined opposition in both countries. In Canada, Conservatives joined with defiant Liberals in decrying the legislation; a junior cabinet member of the ruling Liberal Party resigned in protest. Earlier this month, hundreds of thousands of demonstrators marched through downtown Madrid to voice their opposition to gay marriage. The mayor of Valladolid pledged not to carry out the law, and Catholic leaders urged other government officials to become conscientious objectors.

Using language that Senator Richard Durbin would surely not approve of, the Archbishop of Barcelona likened those officials who disagree with the law but nonetheless carry it out to the Nazis at Auschwitz, who “believed that they had to obey the laws of the Nazi government before their own conscience.”

You know, I seem to remember that the Nazis had some pretty strong views on gays and lesbians, too — do pink triangles ring a bell?

Victor Tan Chen Victor Tan Chen is In The Fray's editor in chief and the author of Cut Loose: Jobless and Hopeless in an Unfair Economy. Site: victortanchen.com | Facebook | Twitter: @victortanchen

“Before Allah punishes us with a second tsunami here in Jakarta, let us ask the police to disperse this event.”

— Soleh Mahmud, head of Indonesia’s Islamic Defenders’ Front (FPI) party, speaking as members of his faction stormed into a club in Jakarta that was hosting a transvestite beauty pageant.

Such a disruption is not unusual for the FPI, which has several thousand members and has previously conducted raids on bars and other venues that it considers to be flagrantly flouting Islamic values as codified in Sharia law. Unsurprisingly, the FPI materialized during dire economic times, as a result of the 1997 financial crisis in Indonesia, and the group advocates the implementation of Islamic law in Indonesia.

With 63 percent of church-going Americans voting Republican, it seems self-evident that the vocal and visible Christian right would enjoy a monopoly on political influence. Now Patrick Mrotek has decided to pit faith against faith and has founded what he hopes will be the voice of the Christian left — the Christian Alliance for Progress.

The Alliance’s goals are explicit and include exerting political influence and addressing issues that have a particularly strong resonance for religious groups and individuals, including the obviously contentious issues of stem cell research, abortion, and gay rights advocacy.

The publicized aim of the anti-gay “Love Won Out” conference in Seattle this weekend is to “heal” homosexuals. The Stranger’s Wayne Besen believes otherwise.

The organization behind the conference, Focus on the Family, contends that homosexuality is a choice rather than a genetic predisposition. What is interesting about this, Besen points out, is that

Poll after poll show that when people believe that homosexuality is inborn, a dramatic and undeniable shift toward full acceptance occurs. A November 2004 Lake, Snell, Perry, and Associates survey showed that 79 percent of people who think homosexuality is inborn support civil unions or marriage equality. Among those who believe sexual orientation is a choice, only 22 percent support civil unions or marriage rights.

Besen concludes that “Love Won Out is not about changing gay people – which isn’t possible – but about changing public opinion.” As The Stranger’s Dan Savage writes in “It’s War,” another article in the weekly’s Queer Issue 2005,

“We’re at war. There’s the shooting war, of course, the one over in Iraq. There’s a war at home too.”