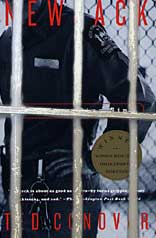

Ted Conover just feels familiar, as if you have been introduced somewhere before. He has a simple face with tired, intelligent eyes and a soft voice. Any number of humble identities could suit him: a small-town lawyer in a smart pair of suspenders; a Northern California dude growing a couple of acres of pot; a brainy priest who nonetheless likes his scotch. Your last guess would be a tough-guy prison corrections officer, which, in fact, he was, roughly 10 years ago.

Conover was a guard at Sing Sing Correctional Facility, New York state’s toughest prison, for just shy of a year, but the job marked him. Like a soldier returning from war, nearly a decade later he says the unusually brutal prison visits him when he sleeps. Yet, unlike tight-lipped vets who often refuse to talk, Conover has, for the past two years, taught a class of New York University journalism students from his troubling book about Sing Sing, Newjack. He not only discusses the violence that he witnessed, but the violence he condoned as a rookie guard. The graduate seminar is called “The Journalism of Empathy,” and it seems a class long overdue.

During spring 2007, the seminar met on Mondays in the Carter Building, a block from Washington Square Park. If the building was a bit rundown — worn carpets, creaky elevator, and gloomy stairwell — the journalism students inside it were generally not. The half dozen lingering outside the classroom and those walking up and down the halls had surprisingly fresh faces. They all seemed a little young, a little undergraduate.

Conover arrived at the classroom carrying a brown shoulder bag, dressed in a black jacket with a black knit cap, looking like a merchant marine arriving from the docks. Sophisticated, even savvy, he didn’t seem to have one ounce of guile. But this gentle bearing was misleading.

In the 1990s, Conover asked New York corrections officials if he could write a story about a trainee going through boot camp. When they refused, he quietly applied for the job. On his resume, he noted a bit of journalism experience, but left off his ties to The New Yorker and the two books he authored. He turned in the application and forgot about it. Two years later, a letter arrived ordering him to report for training in three days, and while Conover knew being a corrections officer (CO) would be tough, how bad it actually became was shocking.

At New York University, Conover sat with his students at a long, brown table, with a cup of coffee and a pen. Behind him were a large whiteboard and a jumble of audio visual equipment. He had an unshakable cold. He said quietly, “I apologize. I hope I don’t lose my voice.”

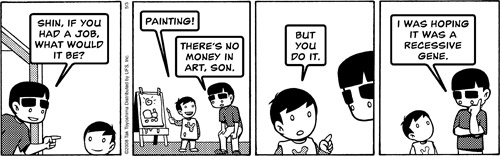

Using first person, or “I,” in narrative nonfiction to empathize with the subject can be quite tricky, said Conover. A writer has to get uncomfortably close to the person, the subject. And the subject can often feel misled or betrayed, or can suck the journalist into his world, blurring the lines to an impossible degree, sometimes destroying the writer’s integrity. So Conover, who has an anthropology degree, relies on an ethnographic technique called “participant observer” to help his students negotiate the line between “I” the journalist and the subject.

Curious about their work’s legal and moral complications, a young woman at the end of the table was worried. What if she witnessed something clearly illegal? As a journalist, do you get involved?

“I mean, what do you do? Would you be considered an accomplice?” she asked. “I mean you’re not including it in your work, but if you’re aware of it and you’re taken in for questioning, you can get in a lot of trouble.”

Conover started nodding even before she finished her question. Does a journalist stop being an outside observer when witnessing, say, child abuse?

“So I guess I’m just wondering,” the girl went on. “My question is: Where is the line?”

“Yeah,” said Conover, his voice becoming more raspy.

“… Is there a line? Do you flirt with the line? …”

“There’s gotta be a line,” he said, still nodding. “You have to have a line.”

Bizarro World Romper Room — with guns and iron bars

Conover’s own line blurred to an impossible degree while at Sing Sing, but a year after leaving the prison, it finally disintegrated. Just months before Newjack was published, in September 1999, he had begun recovering his life with his wife and child. He was lying in bed at home with the television on, his eyes closed. Exhausted. That’s when he was confronted with the past that he was trying to leave behind.

Sing Sing had done a tap dance on Conover’s psyche. In those winter mornings before going on duty as a guard, he sat in his car steeling himself before walking through the frozen gates. Guessing when the day-to-day violence particular to prison might boil over was unnerving and agonizing. He hated the job.

One guard Conover wrote of in Newjack, a real bastard by most standards, had once been taken hostage and tortured by inmates who seized the prison many years earlier. Conover later discovered that the guard’s rigorous, insulting, and unbending professional ethic partly arose from the fear of that happening again. Prison was basically “Bizarro World Romper Room” with guns and iron bars. Relationships with prisoners were stark and authoritarian, and the inmates challenged the guard’s authority daily in a thousand maddening ways.

Sometimes, they were relentlessly childlike: begging to take a shower, refusing to lock up, hanging sheets on the bars, breaking the little rules — “Oh please, come on CO! Come on, pleeeeeaaasse!” Or the inmates would give him a long stare that promised murder. Sometimes the bitterness would cross over into random assaults. Conover was sucker-punched in the head once when he walked past the cell of an infuriated inmate. Women COs had sperm flung on them. One inmate squirted piss from his mouth onto passersby.

Civility inside Sing Sing was not an option. And Conover, a thoughtful man searching to illuminate life’s daily contradictions, could not afford to be scared. To a prescribed degree, COs were allowed take down violent inmates, and Conover found that sometimes he longed to inflict undue pain.

“Guards don’t dare admit that all of us at times feel like strangling an inmate,” Conover wrote in Newjack. “That inmates taunt us, strike us, humiliate us in ways civilians could never imagine, and that through it all the guard is supposed to take it.”

Conover had not anticipated Sing Sing’s brutality. But he embraced it, slowly, immersing himself in the prison system’s logic both as a guard and as a journalist. Conover’s immersion journalism came from his study of anthropology at Amherst College (Massachusetts) in 1980. There he mastered the techniques of the participant observer, which ethnographers rely on to study their subjects, often living with them for extended periods of time. But while engaging a native is fine, going native is a bad idea. Using a set of research strategies — informal interviews, long-term immersion, self-analysis — the participant observer method helps keep the anthropologist oriented and aware of his ever-evolving relationship with his subjects.

One day, a well-read prisoner named Larson passed Conover an outdated book about anthropology through the bars. The book hailed from the days when the science tried to break down people into racial categories.

“Ah yes,” I said. “They used to worry about this stuff a lot.”

“Who?”

“Anthropologists.”

Larson stared at me. “What’s your story Conover?” he asked a moment later. “You’re not like the other COs here.”

“What do you mean? You mean because I’m not from upstate?”

“No, it’s something else. The way you think and the way you walk.”

During his nine months at Sing Sing, Conover told a few friends what he was up to; otherwise, he kept his mouth shut and stuck it out until New Year’s, when he felt he had a natural ending to tie up the book. He held on for the spectacle of inmates celebrating the holiday with controlled fires set ablaze throughout the prison. And he also held on to satisfy his pride. Then, to the relief of his wife, he finally left.

But Sing Sing had seeped into his private life — a civilized world where education and kindness were not considered weaknesses. His marriage had become strained. He was physically exhausted and mentally divided in half. Every night, when he returned home from the prison, he retreated to his office through the back door, without telling the babysitter or his wife. He would type up his day, he understood later, to escape the brutality and peaceably reconcile his double life as best he could.

Though Conover quit Sing Sing, there was one prisoner he couldn’t leave behind: Habib Wahir Abdal, who was serving 20 years for rape, his second prison term. Abdal was one of those poor clichés, the prisoner who swore he was innocent. Whenever the two chatted, Abdal insisted he hadn’t done it. After a few looping conversations, Conover became weary and disappointed at Abdal’s denial. There was no point in arguing, and so Conover just nodded and would say, “okay, okay.”

Then, almost a year distant from the nightmare, free from the daily lies and deception, while lying in bed in the flickering glow of late-night television, Conover stirred to watch the breaking news. He opened his eyes. And he suddenly discovered he was in fact on the far side of a line he hadn’t seen.

“They didn’t even get around to mentioning his name until the end,” says Conover. “I looked at the TV, and out of Green Haven comes Habib and his lawyer, Eleanor Jackson Piel, and Barry Scheck. And I thought ‘Hoooooly shit! He was telling the truth.’”

Mama Piel

As literature, Habib Wahir Abdal’s life story was knitted together as tightly as a Dickens novel. It even had a perfect, melancholic ending. Abdal died in his bed, a free man, in 2005.

His body was found, still warm, by his lawyer, Eleanor Jackson Piel, who had fought his legal battles on and off since 1969. Piel traveled to Lackaw, New York in 2005 to discuss Abdal’s ongoing civil suits, and found him lying in his bedroom. She laid her hand on his body. His eyes were closed. He used to call her “Mama Piel.”

“Yeah, it goes back a long time,” Piel says fondly, while sitting at her desk in her Upper East Side law office.

In a black suit with a silver butterfly brooch on her lapel, Piel’s dark hair was pulled taut into a bun, giving prominence to her handsomely creased, hawkish face. She recounts Abdal’s life as if it were a long-forgotten gem rediscovered in her jewelry box.

She first met Abdal years before he was falsely convicted of rape, before he converted to Islam in prison, back when he was named Vincent Jenkins, a young hustler arrested for homicide in New York City in 1969.

“Evidently he won a large bet, and other people knew he had money and were chasing him. And I think they found him in a house. They came after him. And one of them slit his arm. He ran away and he got a gun,” Piel says, describing the circumstances of Abdal’s manslaughter conviction after he killed a woman and shot a man. “And there were witnesses who saw these people chasing him. I contended he was not guilty because it was self-defense.”

Piel fought the conviction for years.

“I was very emotional. I was very upset,” says Piel, and then she smiles as if a little embarrassed. “Oh, I was younger then.”

After serving his manslaughter sentence, Abdal moved to Buffalo, New York in 1982, where police snatched him off the street and falsely charged him with rape. They manipulated the victim to choose Abdal from a line-up, Piel says angrily, and convicted him in 1983.

Plot twist: Piel’s husband, Gerald Piel, was the publisher of Scientific American. After reading a few articles on DNA testing, Ms. Piel decided to have samples from the rape kit tested. But DNA testing in the late ’80s was “shaky,” Piel explained, and if Judge Elfklin, a federal judge in the Northern District — notorious for slow rulings — hadn’t sat on the case for years, premature testing might have failed to free Abdal.

A first round of tests in 1993 was inconclusive. But five years later, Piel, ready to try again, asked Barry Scheck of the Innocence Project, who specializes in DNA exonerations, what he thought of the Boston lab she had used previously and whether she should do so again.

“Barry Scheck said, ‘Oh that’s a terrible laboratory! Don’t send it to that laboratory!’” says Piel, laughing. “He said there’s only one man who can do this, and that’s Ed Blake, and he’s out in Northern California!”

Within a year, Abdal was free. Under the fair compensation laws in New York State, Abdal’s attorneys, Scheck and Piel, sued for $4 million dollars. When the state offered a $2 million settlement, Abdal said “no way.”

Abdal wanted his day in court and a jury to proclaim his innocence “and that was that!” Piel said while laughing, “We had no idea what to do! Then Barry Scheck had the idea to start a civil suit for the year Abdal was in jail before the trial, and so Abdal finally took the money.”

Six years after leaving Sing Sing, Abdal died of lung cancer, and his surviving family members contested his will. He had left his millions to his mosque and to a close friend, cutting his family out completely because he didn’t trust them.

“They thought there was some skullduggery going on,” says Conover, who found himself somewhat drawn into the legal battle. The siblings hoped that he would testify that Abdal couldn’t read, to prove that he could not possibly understand any legal papers he may have signed.

“And it was kind of an amazing question to me because I’d always assumed he could,” adds Conover, who had stayed in touch with Abdal over the years, but learned of Abdal’s death months after the fact.

“It was galling when I realized I wouldn’t make a reliable witness about that. I wasn’t sure,” says Conover. “He’d never sent me anything in writing.”

Even the most thorough of journalists can miss an obvious fact. This is true, in part, because presumption is instinctual, a necessary skill in a blindingly hectic world. Likewise, Conover failed to recognize Abdal’s innocence out of necessity: prisoners had to be guilty to justify Sing Sing’s degrading ruthlessness.

Abdal’s role in Conover’s work couldn’t be second-guessed. It was a bruising epiphany for the author to realize his complicity, and so later, when asked to testify against Abdal’s wishes, Conover respectfully declined.

Yet, to this very day, nearly 40 years after they met, Mama Piel is still fighting Abdal’s legal squabbles.

The unseemly production

It was early spring — March — a month after his class discussing the line between reporter and subject. Conover sat looking at his hands as he lectured from Newjack, struggling to be precise as he spoke softly. He seemed to avoid telling the horrific story completely by rote. He said that he often felt guilty for bringing Sing Sing into his wife and child’s lives, but he never mentioned the anguish he felt over helping to imprison Abdal.

A young woman raised her hand. How had the compassionate intellectual sitting at the end of the table become the taciturn disciplinarian of the book? Were there two Ted Conovers? Was the hardnosed, matter-of-fact narrator a literary device? Conover, a bit rattled, explained that even today some part of him was still a CO.

The class was skeptical.

Conover stood up and stepped into character. He became a guard again, returning to a time when Sing Sing COs were outnumbered by the prison’s inmate population and Abdal was still guilty. When Conover had discovered he was as much prey as predator.

A guard needed to control the prisoner and himself — no doubts. This illusion of control was a brutal paradigm his psyche had suddenly recovered, as if he had gone back to the crux of that founding contract between man and state. Egged on by the class, he demonstrated his frisking skills, recalling the days he sometimes found himself at odds with Sing Sing’s violence, reluctant to dehumanize a man. He picked out his tallest student, Michael Tedder, directing him to assume the position. In Newjack, during a horrific frisk, Conover’s worries if a prisoner is ill:

He stood in front of me on a small square of carpet, briefs in his hands. He offered them to me, and I checked them quickly. There was some blood in the seat. “You okay?” I asked. He nodded, and I began directing him through the obligatory motions. But he knew them better than I did and was always a step ahead.

Jackie Barba, a cherub-faced, sharp-witted student sitting in Conover’s classroom, who had studied literature in college, wasn’t completely buying it. Her professor was obviously acting out a role, a humorous facsimile, she thought. “It made me wonder,” Barba said after the class. “You know, whether when he was in it, he was always acting and always a little amused to see himself in that role?” When Tedder looked around, Conover snapped “Face the wall!” The class giggled.

Later in Newjack, while being frisked by a guard, an inmate mutters, “You fucking OJTs are a pain in the ass.”

“What?” The officer asked.

The inmate took one hand off the wall and began to repeat the phrase, but was immediately jumped by the frisking officer and several others. When I heard about it, I was proud, because it showed we weren’t wimps.”

To endure Sing Sing, Conover reluctantly embraced its logic, both as a reporter and as a guard. Proud of the violence and embarrassed by his power, it split his psyche in two. But when forced to, he chose to exercise the brutal requirements Sing Sing demanded.

“I think taxpayers are quite happy not to know the details of all the dirty work that is done in our names,” says Conover over the phone in a soothing voice, “just as we’re happy not to know the details of how our hotdogs are made, or everything that’s going on in the kitchen. In fact, we pay not to know about that. So I’m always interested in the work that seeks to narrow that distance and implicate consumers in the unseemly production of something we need.”

Yet, even as Conover taught Newjack with his “prisoner” in a pat frisk stance, his thoughtful students — some amused, some unsettled (“It was kind of weird,” one said) — had trouble wrapping their heads around their professor’s post Sing Sing rationale. Though none ever doubted their professor’s sincerity, a few still had trouble accepting his willingness to embrace an authoritarian self.

Being one of the few male students in the class, Tedder later noted it was likely why he was picked for the frisk. That Conover got into fistfights or was beat up while working at Sing Sing surprised him. “How could this sweet man do this?” said Tedder, adding “but people really are multifaceted.”

After Tedder sat down, Conover drew a long black line on the white board. He wrote “participant” at one end and “observer” at the other end. His students took turns discussing where their semester’s work placed on the numbered line.

One woman had entered a beauty pageant, but few had come close to full “participant” to report their stories. Allie Zendrian, writing about a self-proclaimed ghost hunter, chose to observe her subject without involvement. Barba observed a class of budding comics take to the stage, terrified to try out stand-up comedy herself. Most students weren’t prepared to cross the line, but all of them now knew better where theirs was.

Conover says he would never do it again, immerse himself as deeply as he had to report Newjack. And frisking down his students, even in jest, suggests that his line is still blurred. An innocent man suffered, and Conover did nothing — could do nothing — because he couldn’t afford to doubt. In fact, it was shortly after Conover finished Newjack — after Abdal was freed and Conover realized his role in the injustice — that the nightmares began.

“There are people who think it’s immoral to be a prison officer. I’m not among them,” says Conover, “and I think it needs to be considered honorable work if it’s done in an honorable fashion. But I never anticipated that the work would involve something clearly as illegitimate as locking up an innocent person.”

Lackawanna

It is not as if Conover hadn’t tried reconciling his role in Abdal’s incarceration. He took time with Abdal when he visited New York City, and they roamed the city together: “I remember him looking around for the fragrant oils he liked to rub on his head,” says Conover. And when six American Yemeni men from Lackawanna were arrested for training with al Qaeda in Pakistan and Afghanistan, Conover, looking for a story, stayed as a guest at Abdal’s house in Lackawanna: “I ended up sleeping on his couch for a couple nights and spending whole days with him.”

He even wondered whether there was a book about Abdal’s life — it was never written. But Conover did appear with Abdal at the bookstore Talking Leaves in July 2001, shortly after Newjack came out in paperback.

“I went up to Buffalo and saw him the morning of my reading, and he asked if he could come. So he did. He ended up being a part of the whole presentation,” says Conover. “He brought his prayer rug and his tape player to my room at the Hyatt when I changed, so he could do his evening and afternoon prayers.”

Talking Leaves employees pushed back the bookshelves, sliding them away and putting chairs in where they could fit them. With 30 seats and standing room, perhaps 100 people attended the modest reading. At the front of the store, at a small table, sat Conover and Abdal, ready to take questions. Conover wore a blue shirt with his sleeves rolled up, and Abdal was in Muslim garb with his silver whiskers, polished bald head, and knotty walking stick, looking every bit the elder wise man. Conover gave his short reading and answered questions. Some he deferred to Abdal, who launched into respectful, if biting, monologues on the prison system, even as the corrections officers in the audience squirmed in their seats.

“It was a very interesting mix,” says Conover, “and my book, I think, attracts a readership that’s somewhat the same. It’s, on the one hand, people concerned about prisons as a social problem, themselves intrigued by prison reform and what my book might suggest for it. And then on the other side, there are people in corrections or law enforcement who know that this profession is sort of a degraded one, and a stigmatized one.”

Post-traumatic stress disorder

The afternoon was all that Conover had hoped for: that Newjack wouldn’t preach to any choir, but would rather “narrow the distance” between natural antagonists, forcing them all to face an uncomfortable truth of the prison’s complicated nature — at the blind spot of reason.

But his deep-immersion, first person reporting, his participant observer methodology, cost him as he sought that dangerous ground. In Newjack’s paperback afterward, Conover wrote that he had discussed his nightmares with psychologists at a medical convention. They supposed his nightmares were post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Conover respectfully shrugged and wrote:

That seems rather a grand name for it, and I don’t want to suggest that I went through anything like what soldiers who saw combat in Vietnam did. But I do think that if you repress something regularly (in my case, fear), it’s going to come back to haunt you.

The general thinking on PTSD is that writing down horrific events helps the traumatized to recover. In a way, the balm is almost too obvious. But only recently has this thinking been recognized in newsrooms like CNN International and the BBC. Frank Smyth, an investigative journalist captured during the first Gulf War in Iraq, suffers from PTSD. Smyth says that much more is needed to support journalists who suffer the disorder. Smyth also happens to be the Washington representative for the Committee to Protect Journalists, and writes for the Dart Center for Journalism & Trauma. He recommends that journalists, who often booze it up to self-medicate, instead confront their emotions by expressing themselves through art or memoir. It seems the brain can literally heal itself through self-expression.

“The act of articulation — writing, drawing, painting, talking, or crying,” writes Smyth with co-author Joe Height, “seems to change the way a traumatic memory is stored in the brain, as if it somehow moves the memory from one part of the hard drive to another.”

Conover, to a degree, instinctively embraced Smyth’s counsel. Typing up his notes night after night while working at Sing Sing, Conover turned them into a Pulitzer Prize–nominated book. If he hadn’t, certainly his PSTD would have been far worse.

But even today, Sing Sing draws Conover back across the line he stepped over many years ago, with it shifting around here and there and undermining his peace of mind. Having sought to narrow the distance between people who often violently disagree, to illustrate the blind spot of reason, the filthy work of being both a guard and a journalist lingers.

“In the dreams, I’m almost always a prisoner myself, not a guard,” says Conover over the phone, his voice always a little distant. “And part of the nightmare I’m involved in is the need to get out of that prison because I’m not supposed to be there. I’m not serving a just punishment. I’m there mistakenly.”

Suddenly, he pauses as if to stop his thought, as if reluctant to say it aloud to a stranger. “And so, so in a way, Habib’s situation goes to the root of some of my worst fears about prison: that a person, that I — that any of us — can end up there wrongfully and have to endure.”

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content