What surprised Sabrina Wolf, when she came out to her American Indian grandmother, was the older woman’s lack of surprise.

“I started by telling her, ‘I’m different,’” the white-haired, soft butch activist recalls. And she had this look of, ‘Yeah, I know.’ And then she said, ‘There’s people like you at home [among Indians], and it’s a good thing.”

In addition, her grandmother advised her, “You’re gonna hear … a lot in your life, that’s it’s a bad thing, here (among white people), but it’s not a bad thing, and you’ll know about it later.’”

Wolf, a lifelong San Franciscan and “urban Indian” of both white and Native ancestry, was taken aback by her grandmother’s nonchalant response — a response which, she later learned, was representative of many Native groups. The idea that various American Indian tribes historically recognized and even gave special roles to untraditionally gendered tribe members was written about in 1968, in an academic article by Professor Sue-Ellen Jacobs. But its wider acceptance has come about more recently with the development of vocal groups of queer Indians who, in addition to mining Indian history for traces of their presence, have created a modern name for people like themselves: “two-spirit.”

Coined in 1990 at an annual conference of queer-identified Native people, the International Two-Spirit Gathering, the term “two-spirit,” encompasses various American Indian traditions of tolerance and celebration of gender-variant people. Unlike modern concepts of sexuality, two-spiritedness refers less to sexual orientation than to gender, reflecting the idea that in a single person, both masculine and feminine energies may reside. Prior to the conference, the concept was referred to by different terms in each tribe: For example, winkte in Lakota, a Sioux dialect, nádleehí in Navajo, or problematically called berdache, a French word sometimes translated as “slave boy.”

As an active member of the Bay Area American Indian Two-Spirits (BAAITS), a group organized in 1998 out of Gay American Indians (a product of 1970s San Francisco), Wolf now knows that two-spirits have a long and respected history within many North American tribes. With her own knowledge of two-spirit tradition, Wolf’s grandmother was receptive to the news that her granddaughter wasn’t straight. In contrast, Wolf hardly considered coming out to her white family, who seemed hostile to queer sexuality.

Similarly, Miko Thomas, a Chickasaw member of BAAITS, originally from Oklahoma, was relieved by his Native father and grandfather’s nonchalance at his coming out — a far cry from his white mother’s unease.

But not all Indians have been accepting. The tradition of giving respected roles to specially gendered tribe members came under attack from colonization and Christianization, was all-but erased in official histories until the 1950s, and still finds resistance today. Reclaiming two-spirit identity is an enterprise fraught with intertribal tensions — made still more difficult by the political endangerment of the Native community. And yet it offers American Indians a unique queer space, one both cozily familiar and excitingly new, organized along different principles than the mainstream, majority-white queer world.

Harlan Pruden, founder of the Northeast Two-Spirit Society, decorates his office with photos of people who are out, proud, and Indian.

Creating a two-spirit community

In New York City, the challenge of organizing two-spirit communities has been taken on by Harlan Pruden, the square-jawed and impeccably put-together founder of the newly-formed Northeast Two-Spirit Society. Leaning back at his desk at New York’s Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) Community Center, where he works as a coordinator of an anti-addiction program, Pruden muses on history, surrounded by splashy photos of drag queens and powwows.

“There was a time on this land in which we did have full equality,” he comments. “There was a gender analysis with an open acceptance of same-sex couples and relationships. There was a place for all of it, and I think that it’s a shame that it’s been ignored.” Pruden sees this history as crucial to current two-spirit identity. “There is a model there that can be reactivated, claimed and worked on”, he says, although he adds hastily, “There is no going back to a traditional model.”

Much of Pruden’s own knowledge of Native practices and attitudes regarding queer people comes from anthropologist Walter L. Williams’ 1986 book, The Spirit and the Flesh. Drawing on interviews in a variety of North American tribes, primarily in the United States, Williams highlights how, prior to colonial interference, two-spirit peoples were privileged to traverse the gender line by walking freely between gendered tents, for example, or taking on both types of gendered work — hunting and beadwork. In many cases, specific ritual roles, like holding the eagle’s wing or blessing marriages, were designated for two-spirit people. Compensation for ritual services meant that two-spirit people often prospered within their communities, and could use their financial wherewithal to support adopted children.

Pruden notes that the current LGBT movement traces its history from events that are largely European, Western, or relatively recent, like New York’s 1969 Stonewall riots, in which gay bar patrons protested a police raid. Of this limited perspective, Pruden says, “To me, that’s bullshit.”

And there is evidence to back him up. The 1980s and 1990s saw a host of publications and research on gay Native traditions. Yet, while Pruden hopes to raise awareness of Native communities’ traditional acceptance, tolerance, and even reverence of gender-variant people, and to draw strength from an authentic queer history, he has no illusions that a complete history can be uncovered, or should be.

According to Pruden, the history of acceptance toward queer identity in American Indian culture has been concealed by two major factors: colonial suppression of Native sexual tolerance, and Christian Indians’ rejection of traditional practice.

Thus, for most American Indians, identifying as two-spirit is a process of discovery, not an organic outgrowth of living in modern communities. Pruden explains that, “even if there is a reactivation or an honoring of two-spirit people, sometimes there’s not even an explanation because of the stigma associated with it.”

Pruden recalls being approached, after a lecture on his Woodlands Cree reservation in Northeastern Alberta, Canada, by a woman who said she finally understood why, during the men’s sweat lodge, the medicine men permitted her gay cousin to hold the eagle’s wing — a role of honor traditionally accorded to a two-spirit person. “[T]hat elder was reactivating and staying true to the tradition,” explains Pruden, “by finding someone who was queer-identified and giving him that high office.” Prior to Pruden’s talk on two-spirit traditions, however, the man’s cousin “had no point of reference, as a straight woman, to know what was happening before her.”

“You have to start looking for things that are incredibly subtle,” continues Pruden, “and if you’re an outsider, or it’s not of your tradition, you can’t even see what’s going on.”

Seeking suppressed traditions of tolerance

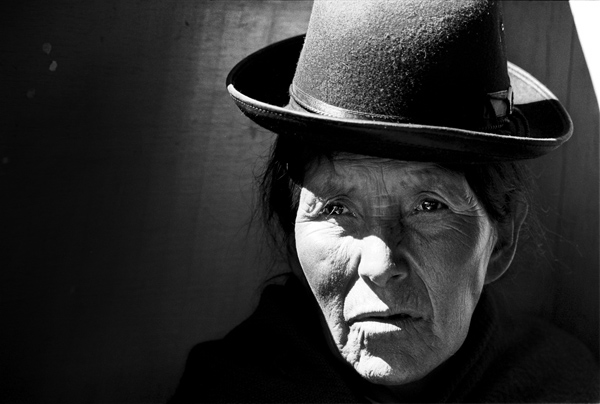

Jeannette Torres, the only female member in the nascent Northeast Two-Spirit Society, angrily recounts the violence visited upon two-spirit people in the colonial era. Torres is of both Peruvian and Puerto Rican heritage, but she identifies mainly with her Incan lineage, having been raised by her father’s Peruvian family who immigrated to the United States in the 1950s. With her pixie haircut, men’s clothing and lipstick, she seems an apt illustration of the gender play inherent in the two-spirit idea. Her black eyes flash as she describes the brutal treatment of two-spirit people by European colonists. “When these colonists came, British and Spanish, they practically decimated us,” she says. “The communities kind of hid what was left of their [queer] people — either hid them, or kept it on the down-low.”

On top of colonial persecution came Christian rejection of the two-spirit tradition. Miko Thomas was combing through his great-grandfather’s Bibles in his native Oklahoma when he found a sermon condemning a Choctaw stomp-dance leader who “either condoned homosexuality or he himself was homosexual.” For Thomas, it was proof-positive that two-spirits had existed previously. “This was the first time that I ever saw anything like this about my tribe.” Previously, a Christian elder in his tribe had told him, “‘There are no gay Indians. There were never any gay Indians.’”

Pruden likewise contends that he has “met elders that just lied to me — Christian elders, rather than traditionalist elders.” At an American Indian men’s health summit, Pruden says, he asked an elder what the word was for “the two-spirit folk. And he’s like, what is two-spirit? So I explained, and he goes, ‘I know what that is — the word is wiktigu.’ Wiktigu is a cannibalistic spirit … a way of keeping kids close to the camp.”

Harlan says his confusion cleared, however, when he heard the elder speak, claiming that the medicine bow is a symbol for the Christian cross, and that braided sweetgrass symbolized the holy Trinity. “I just dismissed what he said, and since then I went seeking actual, traditional elders.”

The lack of open, explicit dialogue about queerness in Native culture means that most two-spirit people, as Thomas laments, “have to go through a book to find where you’re represented as a gay Indian.” The dearth of research on specific aspects of two-spirit life can be frustrating; there’s a notable lack of information on two-spirit women, a gap that Pruden attributes to male privilege: “We live in a patriarchal society. Who has the choice and the power to sit around and write?” He points out that Walter L. Williams himself is a white gay man.

However, some two-spirit people have found that tolerance is nonetheless expressed in Native communities — if not through explicit practice, in quieter, everyday behavior. Ben Geboe, one of the founders of Wewa and Barcheampe, a previous effort at two-spirit organizing in New York City, found that in his Native community, being queer set him apart but did not isolate him. Blue-eyed and pale-skinned, he is usually read, racially, as white, but is of both Sioux and Norwegian descent, and grew up on a reservation in Mission, South Dakota. Growing up, Geboe recalls, “People knew that I was very effeminate.” Though he was sometimes called winkte, a Sioux word that translates, roughly, as “woman’s way,” Geboe explains that “it was never derogatory, never meant as an insult. It was more a kind of joking, a subtle ribbing.” Both his Sioux and his Norwegian family were supportive of his coming out.

Torres shares Pruden’s frustration with the lack of research on women, and adds that she remains uneasy with some extinct two-spirit traditions, as uncovered in books like Williams’s. She explains that two-spirited peoples sometimes did not self-identify, but were designated as such. In a family of five boys, Torres posits, the youngest might be chosen to be two-spirit, and raised accordingly. Selection might be based on a child’s predilection to gender-bend, but it was nonetheless an elder’s selection.

Furthermore, the sexual aspects of some two-spirit traditions, not practiced today, are another source of discomfort for Torres. For instance, in some traditions, a male-to-female two-spirited person would be expected to take a formerly straight male lover. “This man considered it a privilege to be taken sexually or just picked, in general, by a two-spirit person as their partner — it’s like being chosen by a god,” she explains. Sometimes this partnership was only temporary, its duration determined by the two-spirit partner, “And this man [the straight partner] would go back to being straight again.”

Torres is reluctant to revere such practices, which she finds incredible from a contemporary vantage point. “I can’t see taking on a straight lover even if it’s for a million dollars,” she muses. How could a straight man, she wonders, be expected to take on a gay one?

A gender emphasis – “it’s not about who you’re fucking”

Pruden acknowledges the tension between modern, sexuality-oriented identifications and the two-spirit concept. “It’s a gender theory — it has nothing to do with sexual orientation,” he says. “Some nations have as many as five distinct genders. Each has a role and a responsibility as well as a sphere within the context of the community.” However, because “today, it’s gay-identified Native Americans who are two-spirit identified . . . that component of gender is basically taken out in practice.”

For example, Pruden notes that while some two-spirits in reservation settings are taking up traditional two-spirit roles again, such as ceremonial cooking, healing, and telling sacred stories, they “do couple up with other two-spirited people in a contemporary way,” rather than taking a straight identified partner as was tradition. As Torres mentions, it’s not a change that most two-spirit people today would lament.

However, as Pruden points out, the traditional emphasis on gender, rather than sexuality, expands the discussion from sex to society. “It’s not about who you’re fucking — it has nothing to do with sex.” Unlike sexual orientation, gender “something that is distinctly ours — that we perform within the community,” argues Pruden. Two-spirit people, he says, must grapple with the question of “‘What is our role within the community at large?’ not just ‘Who am I sleeping with?’”

The emphasis upon a socially-situated role is, for many Native Americans, a welcome change from mainstream queer communities, which often focus on personal identity as separate from the political, cultural and spiritual spheres that form the foundation of two-spirit groups.

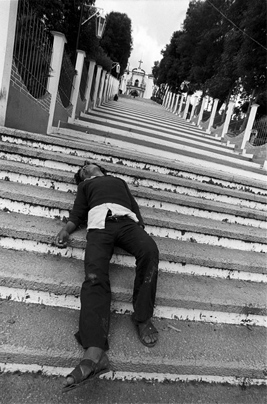

Due to the myriad modern threats to American Indian communities, such as marginalization, poverty, poor education, alcoholism and other diseases, Ben Geboe says, people who identify as two-spirit “are more concerned about the racial and ethnic issues than they are about gay and lesbian issues.” Issues such as gay marriage, argues Geboe, are petty compared to American Indians’ struggle to survive as an ethnic community. “We’re still fighting for land, we’ve still got these social problems, we have the highest incidence of disease,” he says.

Thomas agrees that his primary allegiance, as an activist, is to the Native community. Growing up on his Oklahoma reservation, he explains, “this whole structure around you … says that you need to be politically active,” especially in the hostile political climate generated by anti-Native groups such as One Nation, which has advocated against tribal sovereignty.

Wolf agrees that “gay is second to our role as a two-spirit person walking in the world.” In her view, two-spirit identity is informed by the deep spirituality inherent in Native tradition. “A lot of two-spirit people view themselves as called to a kind of spiritual service,” she remarks.

Wolf feels that this spiritual emphasis, compounded with the problems of “alcoholism and drug addiction on the rez”, lends two-spirit gatherings a different tenor than mainstream queer events. “Our meetings aren’t all about partying,” she says, noting that almost any two-spirit event will include a prayer or speech by an elder.

“There are people of color who are gay, and there are white people who are gay”

The communal concerns of two-spirit people can generate discomfort for them in mainstream queer communities. “The LGBT movement is fighting for equality,” argues Pruden, “but it’s equality in a model that is being basically driven by white privilege.”

Geboe perceives a racial divide in urban gay life: “You can be [white and] gay, live in Minnesota, and come to New York and feel that you’ve arrived in this mecca, and that everything in this world is there to promote your survival as a person.” In contrast, he continues, “You can come to New York as a Native American from South Dakota, and if you’re a person of color, immediately understand that there are two [queer] societies —there are people of color who are gay, and there are white people who are gay.”

Besides their shared political and spiritual concerns, two-spirit people take comfort in not being tokenized in Native settings, the way they frequently are in the larger queer community. Before Wewa and Barcheampe formed, Geboe explains, ”it seemed like we were doing more for the overall gay and lesbian community than we were doing for ourselves,” constrained to perform as ethnic “representatives” symbolizing the diversity of the gay community.

Wolf complains that “in the gay community at large, we’re sort of a novelty, or we don’t exist — because in mainstream society, we don’t exist.” Two-spirit gatherings are one of the few places where Harlan says he doesn’t feel a need to “take count” to determine his comfort level. Normally he says he asks himself, “Is this safe or is this not safe? How many people of color are here? How many other gays?” However, he feels, “When I go to these two-spirit gatherings, I never count. I don’t have to count. It’s very affirming.”

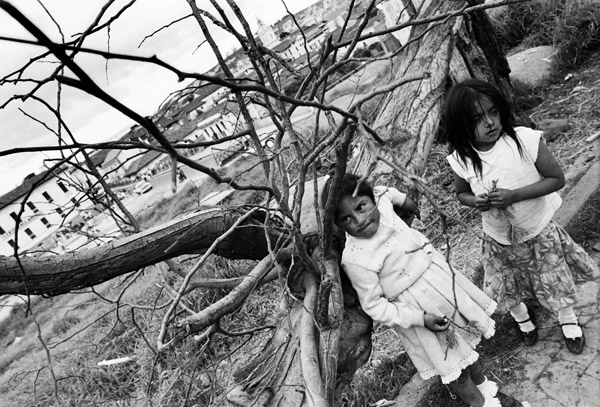

Two-spirit people also draw from experiences of poverty on the reservation that, Wolf notes, are typically far removed from the experience of white Americans. Thomas explains that, for rural gay Indians in particular, the cultural connection is essential as they seek new communities in larger cities. “For us it’s very important to connect with people we identify with. Growing up impoverished is something that unites us.”

Thomas reflects, “You can’t just joke around with Caucasian people, saying, ‘Yeah, when I was a little kid, I used to have to haul water, so we could take a bath.’” In his experience, such anecdotes are often met with disbelief or derision. For the approximately 1.2 million American Indians who live on reservations, however, “That’s just a part of our lives!”

Creating two-spirit culture across tribes

At the same time, the intertribal reach of two-spirit organizing presents its own problems. “Some tribes don’t have a tradition of tolerance of lesbian and gay activity,” Geboe remarks. Consequently, there are a number of Native people who view two-spirit traditions “as an outside thing coming in, and not as something that’s always been there and now is more visible.” He discovered this hurdle himself in an “uncomfortable confrontation” at a Native conference, in which “this elder got up and said that everything we [two-spirit organizers] were doing was wrong.” Intertribal respect, however, prevailed, and it was agreed that the tribes’ traditions differed.

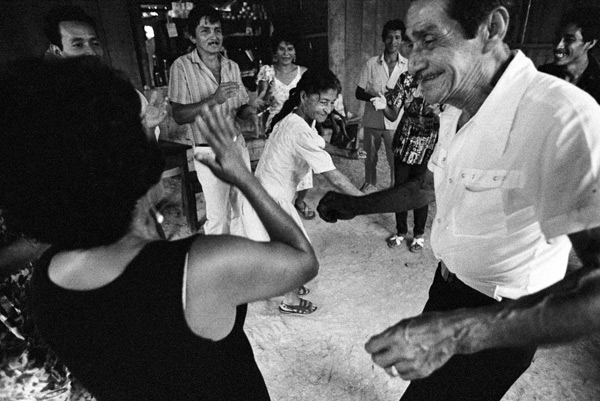

Within two-spirit groups, tribal diversity can also be problematic, but, paradoxically, may produce greater solidarity. “When we come together,” Wolf explains, “we have different traditions around how you say the prayers, and how you have rituals and ceremonies. The interesting this is, when we get together and ask [those questions] we find that, you guys may do this little thing a little bit different” but there’s a basic “connectedness.” In a way, she remarks, “we’re creating two-spirit identity all the time.”

At a time when the queer community on the whole is grappling with its priorities and considering new privileges such as marriage, military service, and adoption, two-spirit organizations like Pruden’s offer an alternative model of queer empowerment.

Reflecting on two-spirit and mainstream gay communities, Geboe summarizes the difference: “The gay way,” he says, ”is that you become gay, you live in the gay community and you do things that identify you with the gay community. The two-spirited way is that you’re a Native American first, and that’s your culture, but there’s also this gayness. But it’s integrated with your culture. It’s something you don’t leave to become.”

Author’s note

Tribal names have been chosen in accordance with the preferred terms of those interviewed. For the purposes of this article, the terms ‘American Indian’, ‘Native American’, and ‘Native’ have been used interchangeably to describe persons descended from the original, tribally-organized peoples of North and South America.

In this article, the term ‘queer’ is used to describe all people who either do not identify as straight, do not identify as the same gender as their biological sex at birth, or both.

STORY INDEX >

The Northeast Two-Spirit Society meets on the 2nd Wednesday of each month, from 8 p.m. to 9:30 p.m. at New York City’s LGBT Center.

BOOKS >

Purchase these books through Powells.com and a portion of the proceeds benefit InTheFray

Two-Spirit People: Native American Gender Identity, Sexuality, and Spiritualityby Sue-Ellen Jacobs, Wesley Thomas, Sabine Lang

URL: http://www.powells.com/cgi-bin/partner?partner_id=28164&cgi=product&isbn=0252066456

Changing Ones: Third and Fourth Genders in Native North America

by Will Roscoe

URL: http://www.powells.com/cgi-bin/partner?partner_id=28164&cgi=product&isbn=0312224796

Living the Spirit: A Gay American Indian Anthology

Edited by Will Roscoe

URL: http://www.powells.com/cgi-bin/partner?partner_id=28164&cgi=product&isbn=031203475x

Spirit and the Flesh: Sexual Diversity in American Indian Culture by Walter Williams

URL: http://www.powells.com/cgi-bin/partner?partner_id=28164&cgi=product&isbn=0807046159

ORGANIZATIONS >

Bay Area American Indian Two-Spirits

URL: http://www.baaits.org

The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Community Center

URL:http://www.gaycenter.org

Northwest Two-Spirit Society

URL:http://www.nwtwospiritsociety.org/index.html

“

In The Fray Contributor

Dear Reader,

In The Fray is a nonprofit staffed by volunteers. If you liked this piece, could you

please donate $10? If you want to help, you can also: